Joséphine de Beauharnais: Patron of the Arts

Joséphine de Beauharnais was born in Martinique as Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. She evolved into the sophisticated and cultured...

Maya M. Tola 20 May 2024

Although most commonly associated with the works of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Mexican muralism has actually been part of the country’s artistic heritage since pre-Colombian times. In fact, we have learned that Mesoamerican civilizations adorned their palaces and temples with murals. They illustrated everything from historical events such as wars to religious ceremonies like human sacrifices. So, here is the history of Mexico as written in the murals of The Big Three.

One surviving example of such ancient muralism is seen in the so-called Temple of Murals. This is located within the Mayan archeological site of Bonampak and dates back to the 8th century CE. Representations of Mesoamerican life by both Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco show the influence of this Indigenous style of painting. We see this, in particular, in Rivera’s The Great City of Tenochtitlan. This work captures the unspoiled beauty and splendor of the Aztec capital before the Spanish conquest.

On the other hand, Orozco uses a more “primitive” style to show the less innocent side of Native American culture. We see this in certain panels from The Epic of American Civilization, especially in one titled Ancient Human Sacrifice.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus completed his first voyage to the Caribbean. Thus began the age of Spanish colonization in the Americas. Shortly afterwards, in 1519, Hernan Cortés became the first European to reach the mainland. Famously, upon arriving on the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, he ordered his men to sink the ships. He did this to make clear to his crew that there would be no turning back.

They had to conquer the Indigenous empires first. In fact, the fall of the Aztec capital marked the beginning of complete Spanish domination over the native people. And we see this change reflected in Rivera’s mural The Arrival of Cortés. Here, he no longer focuses on the impressive temples or beautiful canals of the Aztec civilization. Instead, his painting depicts the slave trade and forced conversions to Christianity that became commonplace under Spanish rule.

In his The Torment of Cuauhtémoc, David Alfaro Siqueiros depicts the conquistadors’ execution of the last Aztec emperor. In many ways, the Spaniards’ methods of “civilizing” the native people were not so different from local religious practices. These had also been seen as savage. So, sadly, the brutality of the Spanish Inquisition in the Americas went on unquestioned. However, this changed when the Dominican friar, Bartolomé de las Casas, published A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. This famous work chronicled the atrocities committed against the native people in what had become the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

By the early 19th century, Spain was losing its control over an empire that stretched across two continents. In 1810 the Mexican War of Independence broke out. This coincided with the liberation of much of South America by the armies of Simón Bolívar. One of the first instigators and military leaders of the independence movement was a priest, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla.

In 1810, he successfully marched his army through the country until he reached Mexico City. This was now the Spanish capital which, significantly, had been built on the site of what was once Tenochtitlan. Significantly, Hidalgo managed to trap the Royalist troops inside the city. Yet, despite being aware of his advantage, he then retreated.

Historians widely believe that Hidalgo made this abrupt decision in order to save his fellow citizens in Mexico City from the pillaging that would inevitably follow the rebels’ victory. Thus, the war continued, and Mexico did not gain its independence until 1821.

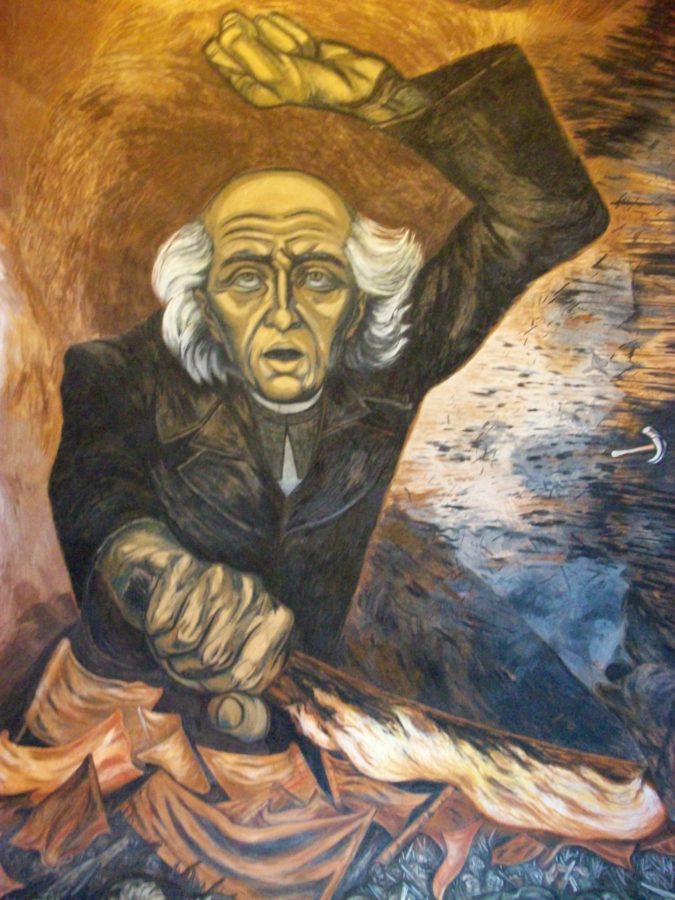

Two of Orozco’s murals commemorate the patriotic services of the revolutionary priest. They are Father Hidalgo and The Great Mexican Revolutionary Law and Freedom of the Slaves. In these works, Orozco presents Hidalgo in a social realist style. This shows the influence his ideas had on the country’s 20th-century revolutionary movements.

The first century of Mexico’s independence was a tumultuous period. It was marked by unstable political regimes, great economic inequality, and a loss of considerable territory in a war with the United States. It was the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz that brought Mexico into the 20th century. However, this ended in 1911 at the start of the Mexican Revolution. Under the leadership of Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, amongst others, the various factions managed to institute constitutional and agrarian reforms. These were implemented after a decade-long conflict that, according to some estimates, had resulted in around two million deaths.

Siqueiros depicts this period in his mural From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution, The People in Arms. In this work, he traces how the extravagant and lavish lifestyle of the aristocracy did much to fuel the anger of the country’s exploited peasants at the start of the revolution.

“Los tres grandes” (or “the big three,” as they are known) dedicated their talents to presenting the history of their country from its origins. In so doing, they left a legacy that continues to inspire new generations of Mexican artists. Yet, at the same time, they preserved an artistic tradition that lies at the very heart of that country’s cultural heritage. Today, the influence of Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros can be seen throughout the country. This extends from the murals which decorate the villages of Zapatista rebels in the jungles of Chiapas to those lining the streets on neighborhood walls of Mexico City.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!