5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

Not so long ago, artists got their pigments from nature. In consequence, every region of the world had its own pigments and shades of colors. In Mesoamerica, two colors stood out, red cochineal and añil blue. This particular shade of red reached Western Europe and fascinated the Old and Modern Masters. On the other hand, colonial Masters used añil indigo. Both became the most imported products, only behind silver. Furthermore, a variant of this blue is the famous Mayan blue. These three dyes are examples of the skill and knowledge of the Pre-Columbian cultures to obtain rare pigments. Let’s make a quick dive into the story of these Mexican colors and their role in art history.

Red cochineal is a Mexican color from Pre-Columbian times. It came from a tiny bug: Dactylopius coccus. According to Bernal Díaz Castillo’s chronicles, they already commercialized it in the marketplace of Tenochtitlan when the Spanish arrived. Cultures used it in diverse ways such as dying textiles and coloring codices. It must have been a precious product since it was part of the tributes the Aztecs demanded from other groups.

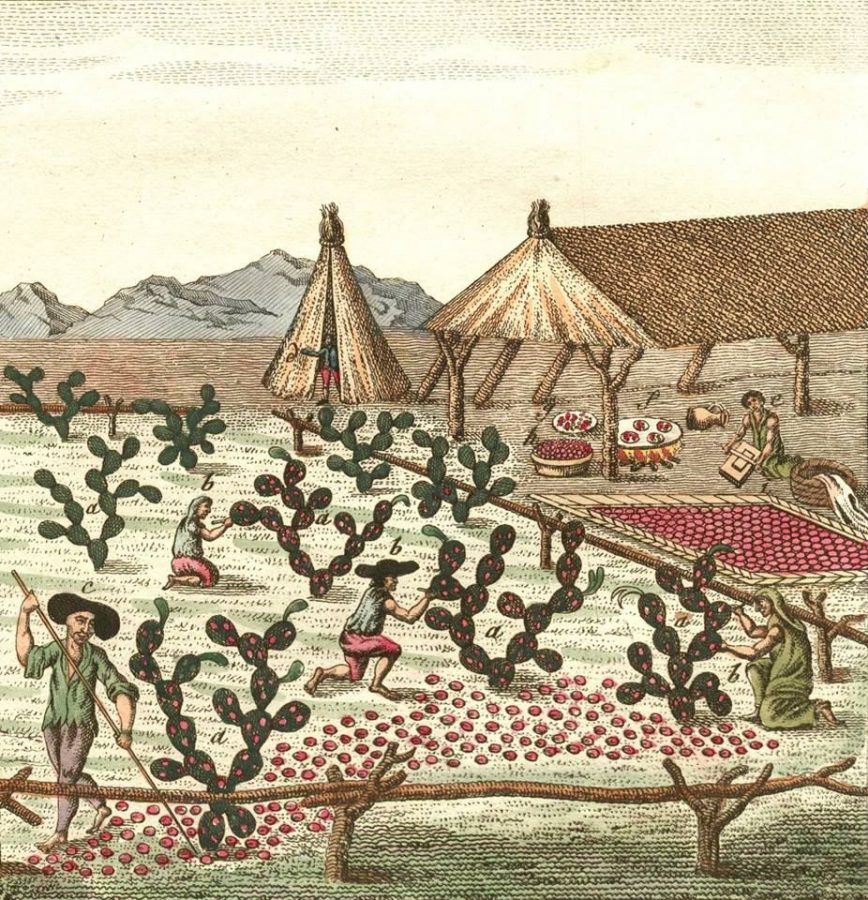

Since it comes from a tiny parasite, the process of extraction was an arduous one. Actually, they had farms to raise these insects. As the female cochineal would stand in the nopal cactus, the workers would collect them and leave them to dry. For this step, either they laid them in the sun or they heated them in a pot. Later on, they crushed the cochineal and the red dye would be obtained.

When the Spanish conquerors arrived, they quickly noticed a particular shade of red in the codices and textiles. It was much brighter and more intense than any other red they had seen back in Europe. Once they learned where it came from, they didn’t waste time and sent it back home. It became one of the most precious items that Spanish conquerors obtained from New Spain. In Spain, it was called grana cochinilla.

It was possible to harvest it in Peru and other parts of Mexico. However, the state of Oaxaca held the highest quality of red cochineal, earning the name of grana fina. In fact, the Spaniards were never able to compete with the skill of the communities there. Therefore, the production of this Mexican color remained almost exclusively Indigenous and few Europeans settled in that territory. This product positioned Oaxaca as one of the most important areas in New Spain.

The red dye became so popular among European artists that it quickly became the second most exported product from America, after silver. As expected, the painters living in port cities got early access to this dye. Tintoretto was the first European painter to use the red cochineal. In his painting, Christ carried to the tomb, he used the cochineal on the figure carrying Christ as well as on the clothes under him. Another Venetian who added the red cochineal to his palette was Titian.

The red cochineal was soon associated with power and royalty. The nobility and aristocracy began to demand it in their commissions. For example, Louis XIV requested the use of red cochineal on the royal bed curtains and chairs of Versailles. Or the British, who used cochineal to dye the red uniforms of the army officers. Furthermore, it is possible, though not confirmed, that Anthony van Dyck used it for his Portrait of Agostino Pallavicini. Just look at the vibrancy of that red.

Quickly, the red cochineal reached farther parts of Northern Europe. In fact, masters such as Rembrandt included it in their works, among others. We can find it in one of Rembrandt’s most famous paintings, The Jewish Bride. Surrounded by a dark background, the woman’s red dress shines.

Of course, the Spanish painters couldn’t waste the chance to use this unique pigment. One of them was Francisco de Zurbarán in his Penitent Magdalene. Additionally, it is believed that Velázquez included this red in his masterpieces, too.

Meanwhile, across the pond, artists in New Spain didn’t waste the opportunity of utilizing this precious color so close to them. Cristóbal Villalpando applied it in his Virgin of Guadalupe as well as in his Marriage of Mary and St. Joseph.

As new synthetic pigments appeared on the market, cochineal dye production decreased. Moreover, after the independence of Mexico, the market started to crumble. However, thanks to the Impressionists, the Mexican color was saved. In fact, Renoir’s Madame Léon Clapisson has cochineal in the background. Unfortunately, the red cochineal in canvases tends to fade easier than in textiles. As a result, today the painting has lost its vibrant red. However, thanks to technology, a digital coloration shows it as it would have looked originally.

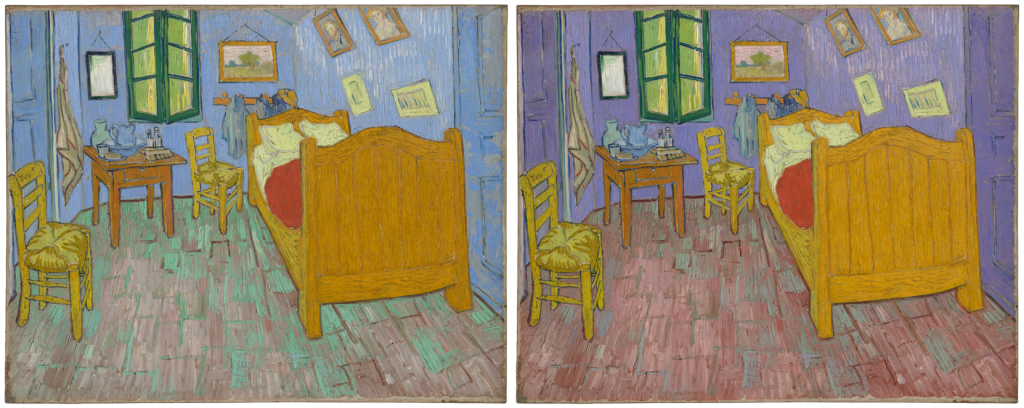

The Post-Impressionist, Vincent van Gogh, was the most enthusiastic in using the red dye. In fact, there’s a piece of Mexico in his famous bedroom in Arles. Instantly, we can detect the red in the bed. However, there’s more. According to a letter to the artist’s brother, Theo, the original walls and doors were violet and lilac obtained with cochineal. Furthermore, the floor had a pink tone too. He was aiming at a sense of peace for the viewer. Both the Art Institute of Chicago and the Van Gogh Museum had made a digital restoration of the various versions of the painting.

Another highly precious Mesoamerican color was añil blue, a type of indigo. Although indigo exists in many parts of the world, this particular shade of blue comes from the añil (Indigofera suffruticosa). This species is mainly found in the Southern and central states of Mexico. The Mesoamerican cultures called it xiuhquilitl, meaning blue herb. It has been found in several ruins, murals, ceramics, textiles, and codices.

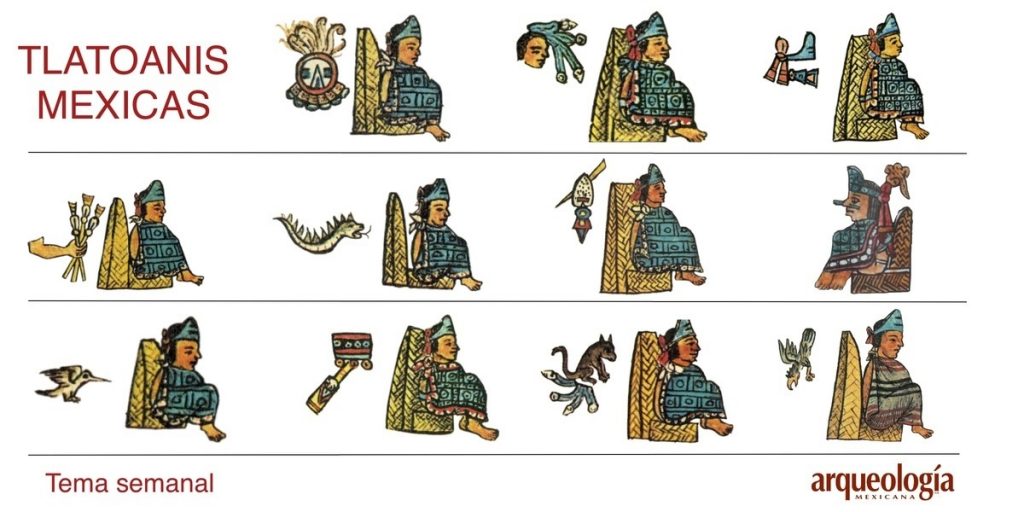

Añil denoted power since pre-Columbian times. Actually, they used it for the xiuhtlalpilli tilmatli, a royal cape exclusively for the tlatoani (Mexica’s religious and military leader). And like red cochineal, became one of the most exported products from New Spain.

There is an herb in the hot lands called xiuhquilitl, they soak this herb and squeeze the juice from it, and pouring it into glasses there it dries or curdles, with that color it is stained dark blue and resplendent, it is a precious color.

Fray Bernandino de Sahagún, 16th century. Cienciario.

As cochineal, it requires an elaborate process. Basically, they crushed the leaves and branches of the plant and put them at the bottom of a pool with stones. Later, they filled it with water and left it there for about 12 hours. After this, they stirred the water to oxygenate it. Once they saw a white foam, they left it to settle the blue at the bottom. Once they drained the water and filtered the blue tint through a fine cloth, they got a mass. As it dried, they obtained the powder.

Although the colonial center of production was located in El Salvador, it was produced in Mexico too. Even today, Mexican communities in the Southern region keep using the same pre-Hispanic process.

Añil was mainly exported for textiles. Nonetheless, various colonial artists might have used it in their works. Let’s remember that blue was a costly pigment at the time and, most likely, colonial artists wouldn’t have been able to afford it. Nonetheless, great masters of New Spain managed to include bright blue tones in many of their works. For example, it’s possible that José Juárez (1617 – ca. 1664) used this pigment to paint the Virgin’s dress.

Probably, the best example of the use of colonial Mexico’s blue was Baltasar de Echave Ibía’s (ca. 1585/1605–1644) The Immaculate Conception. This artist even received the nickname “the Echave of the Blues”.

Probably one of the main variants of añil is the famous Mayan Blue. This culture mixed the añil with attapulgite clay. It was a very laborious process, having to heat the ingredients up to 200°C. But it was worth it. Indeed, what surprised scientists and art historians the most, apart from its vibrancy, was its resistance to harsh weather conditions. They used their own blue and not only for paintings. Professionals have identified Mayan Blue in murals, pottery, and other ritual objects. The earliest example comes from the murals of Calakmul dated ca. 150 BCE.

Unfortunately, there is no written evidence of the use of Mayan Blue during colonial times or after. If they knew this rare blue pigment existed, they would have exploited it too. Furthermore, while Mayan Blue was perfect for murals, its use in canvases wouldn’t get the same result, similar to cochineal. In fact, scientists weren’t able to figure out its production process until the 1960s. Today, they are still studying it.

Synthetic pigments, bad management, and Mexican independence deeply affected the production of grana cochinilla. Sadly, Oaxaca was never able to find a product that could bring them the same prosperity and remains one of the most impoverished states of the country. As Europeans discovered the chemical formula of añil, this dye lost its importance too. However, as the demand for natural dyes grows, it is possible that both Mexican colors will rise up once more.

Barbara C. Anderson. “Evidence of Cochineal’s Use in Painting.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 45(3), 337–366, 2014. Accessed 4 Aug 2021.

Jeremy Baskes. “Seeking Red: The Production and Trade of Cochineal Dye in Oaxaca, Mexico, 1750–1821”, The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400–1800. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Aldershot, Hampshire, UK, 2012.

Amy Butler. “The Bug That Had The World Seeing Red.” Smarthistory. Accessed 5 Aug 2021.

Sarah Cascone. “In Pre-Industrial Europe, Blue Pigments Were Exceedingly Rare. But an Ocean Away, the Maya Had Their Own, Widely Available Blue.” Artnet News. Accessed 7 Aug 2021.

Elisabeth Malkin. “An Insect’s Colorful Gift, Treasured by Kings and Artists“. New York Times, 2017. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

“Misterios y bondades del añil“. Franz Meyer Museum. Accessed 8 Aug 2021.

Rafael Salgado. “Un azul olvidado: El añil mexicano.” Cienciario. Accessed 7 Aug 2021.

Devon van Houten. “The rare blue the Maya invented“. BBC Culture. Accessed 8 Aug 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!