5 Myths About Dada Deconstructed

Considered a pivotal moment in art history, a lot has been said about the Dada movement. Rejecting everything (even themselves!) Dada members...

Amélie Pascutto 25 May 2022

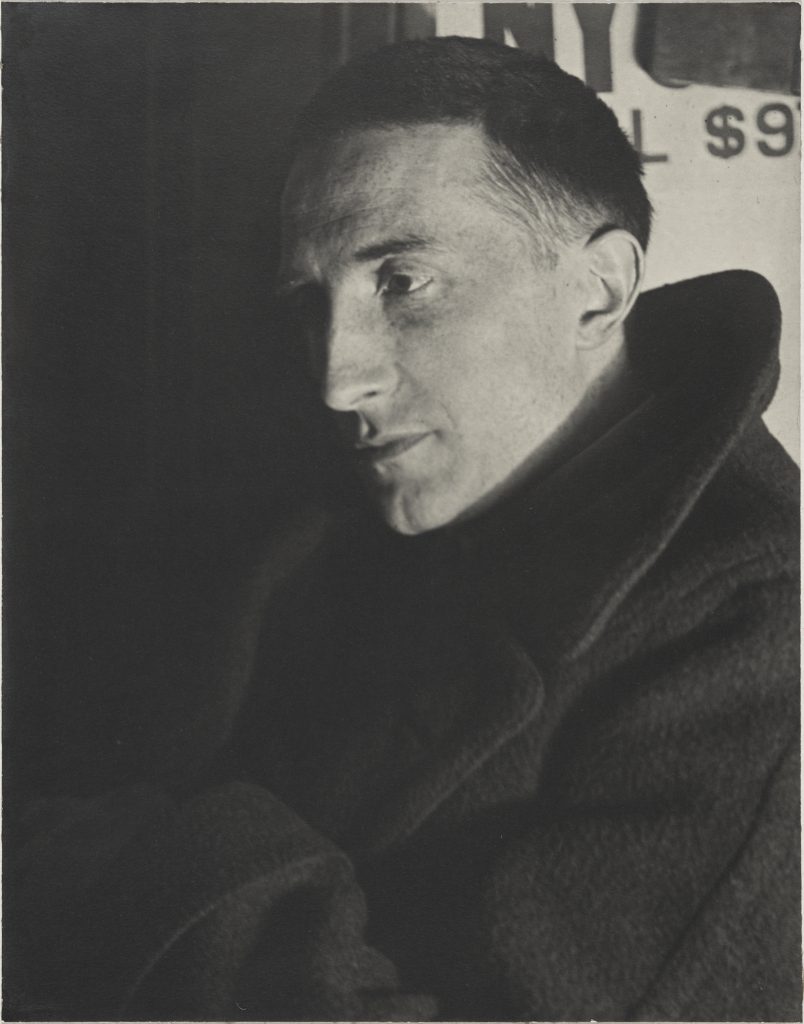

Few artists have been as versatile and as bold as Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). He was a painter, a sculptor, and a photographer; he was a seminal member of the Cubists, a major progenitor of the Dadaists, and the bedrock of the next century of conceptual art; he was even a world-class chess player. However, of all Duchamp’s many daring artworks, the one that best captures his originality, boldness, and shocking disregard both for rules and for taste is perhaps Fountain – an upside-down urinal.

Man Ray, Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1920-21, gelatin silver print, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, USA.

As the story goes, while shopping at a local hardware dealer called J. L. Mott Iron Works in 1917, Duchamp (who was already a famous painter by that time) purchased a commercial urinal off the shelf. Back at his studio, he signed it “R. Mutt,” a play on words referencing the Mott store, the popular cartoon strip “Mutt and Jeff,” and the name Richard, French slang for “money-bags” (with its own humorous double meaning, in the context of a urinal). Finally, after adding his largest contribution to the piece—turning urinal on its side—Duchamp submitted it to a modern art exhibition in 1917. The organizers, the Society of Independent Artists, were stumped.

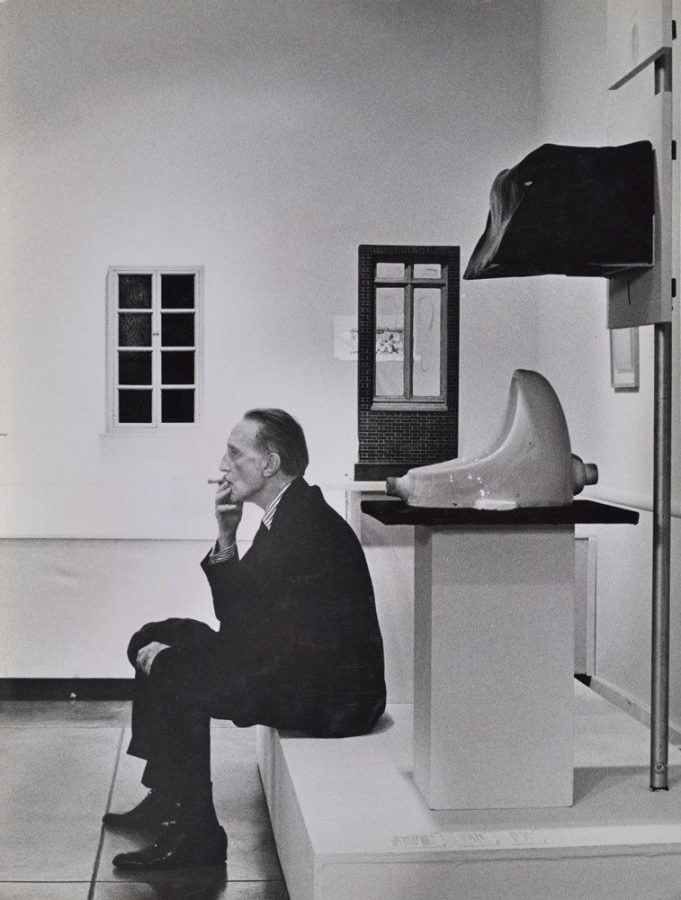

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, “The Blind Man” number 2., published by Beatrice Wood, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Could this urinal, a commercial product designed for a purely functional purpose, even be called art? And could the person who submitted it, having not played any part in its design or manufacture, be called an artist? Eventually, the Society board decided no on both fronts. Unable to reject it outright, they hid it off in an obscure corner of the gallery behind a partition.

The New York Dada scene was outraged at Fountain‘s treatment. Later that year an editorial was published in the art journal The Blind Man which made the case for why it was indeed a work of art. The essay argued that whether or not Mutt (Duchamp’s pseudonym) built the urinal is irrelevant because he arranged it in a unique way and presented it “under [a] new title and point of view,” and therefore “created a new thought for that object”. This, they insisted, was all any artist ever did. Is there any fundamental difference, after all, between Duchamp’s Fountain and, for example, Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889)? Just as Duchamp didn’t make the urinal, Van Gogh didn’t make the night sky—both only altered and re-presented their subject.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

One of the central ideas of Duchamp’s career was a rejection of what he called “retinal art” – art that only pleased the eye. By contrast, Duchamp himself preferred and wanted to create art that pleased the mind, stimulated deep thought, and introduced new ideas. Fountain is certainly not pleasing to the eye, but it does raise questions about the nature of art itself. Why are certain objects classified as “art” but not others? What matters most in an art object: the object itself, or the idea behind it?

In the years since, a staggering amount of art movements, artworks, and artists can trace their lineage back to Fountain. When Andy Warhol made a series of paintings of Campbell’s soup cans, Marilyn Monroe headshots, and newspaper photographs in the 1960s, similar questions were raised about whether these counted as art. These were not traditional subjects of art but rather a far cry from the works of Rembrandt, for example. At Warhol’s art “Factory,” where assistants did much of the grunt work executing his ideas, some questioned again who the real artist was. Warhol was not the one manufacturing many of his own artworks.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962. Museum’s website. © 2022 Andy Warhol Foundation / ARS, NY / TM Licensed by Campbell’s Soup Co.

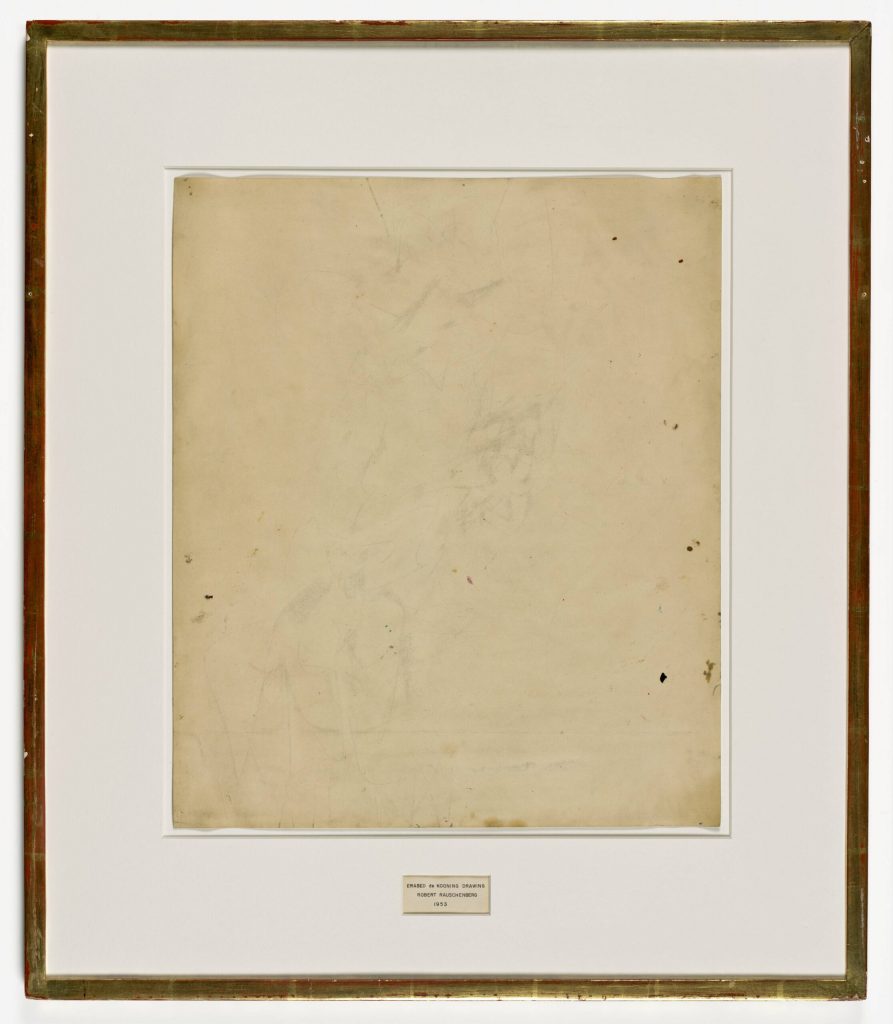

Similarly, in Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), Robert Rauschenberg quite literally took a drawing of famous Abstract Expressionist artist Willem de Kooning, erased it, and presented the now-blank paper as his own artwork. Who, in this case, is the artist? Rauschenberg, de Kooning, or neither?

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA, USA.

In the 1980s, now three-quarters of a century after Fountain, Richard Prince took the idea of appropriation even further. He chose some cigarette ads in a magazine, featuring stereotypically masculine images of cowboys riding in the desert, took photographs of the magazine page, and submitted them to art galleries. Although it’s easy to mock Prince’s work ethic or to call him a thief, these photos raise a serious question: Why were the original photographs not considered serious art in the first place, if they were beautiful enough to play in a gallery show? And what, therefore, is the function of the art gallery in society?

Richard Prince, Untitled (Cowboy), 1989, photograph, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA

All of these artworks, from Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Prince, in some way replicate what Duchamp did decades earlier. They appropriate objects or images created by others, they present subjects often considered in poor taste, and they question the nature of art and the artist. In this way, Fountain, and Duchamp’s other works, influenced an incredible range of art including happenings, Fluxus, performance art, conceptual art, Pop Art, and more individual artists than it’s possible to name. However, if we only consider so-called high art (the stuff venerated in museums and art history books), we miss just how vast Duchamp’s legacy is.

Julian Wasser, Duchamp smoking in front of Fountain, Duchamp Retrospective, 1963, Pasadena Art Museum, CA, USA. Artsy.

Appropriation is now the primary method of most internet art in the world. Think of the song remix, the mashup, the parody video, the YouTube poop, or the meme. All of these take an artwork that someone else has made and add some new spin to it. When one watches a YouTube video, for example, in which the uploader takes a clip from the sitcom Roseanne (1988-1997), puts it in slow motion, and comedically zooms in on Roseanne’s face as she says “power tools,” you are witnessing a direct descendant of Duchamp turning a urinal on its side and submitting it to an art gallery.

It might be hard for us to take internet art seriously today, but it was equally hard for the art establishment to take Duchamp’s urinal seriously in 1917. With the benefit of hindsight, though, it’s clear that Fountain is one of the most important artworks of the 20th century for the ideas it introduced and the staggering number of artists it influenced. What other world-changing art do we have our own eyes (or retinas) closed to today?

Author’s bio

William Kohler is a freelance writer, film critic, and teacher. He has a master’s degree in film & media studies from Southern Illinois University.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!