Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

This masterpiece, La Joconde, is all about codes, reversals, play with conventions, and provocation. In other words, it’s an epitome of Dada and Marcel Duchamp‘s entire oeuvre.

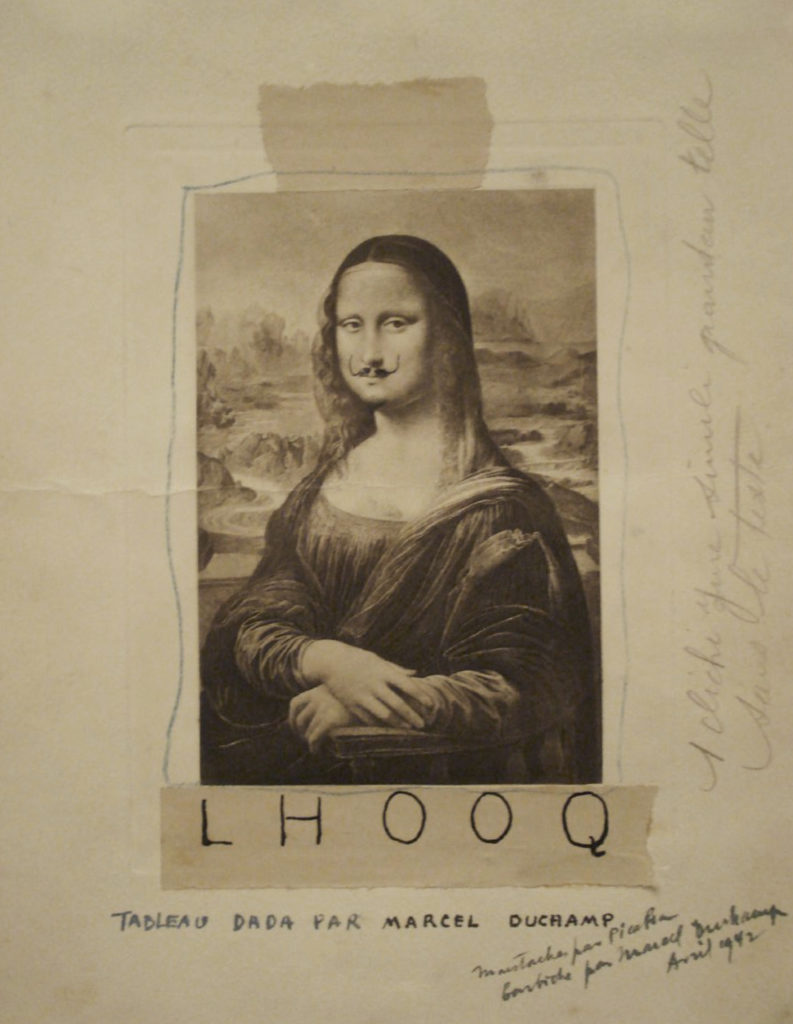

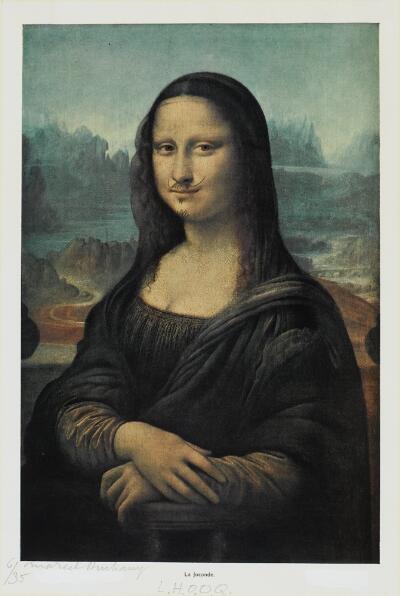

We all did it at some point in our lives: we drew a mustache on somebody’s printed face in a color magazine or a street poster. I used to do it on the covers of my grandma’s crossword booklets. Well, Marcel Duchamp, the father of the Dada movement, did the same on a postcard of Leonardo da Vinci‘s Mona Lisa. Yet, this time, it was not just an ‘immature prank’ but turned out to be a work of art. Why?

Marcel Duchamp was one of the first artists of the 20th century who began questioning the status of art in the contemporary world and the criteria according to which an object became an artwork. He came up with an artistic technique called ‘found objects’, which relied on a basic principle: you find any mundane object, you alter it slightly by adding or subtracting something to/from it, you call it a piece of art. La Joconde was too made exactly in the same way, and it instantly became one of Duchamp’s most famous readymades and a symbol for the Dada movement.

Duchamp’s idea worked on a basis of defamiliarization, which was meant to spark some reflection in the viewers who would be confused looking at an everyday object set in an unsuitable setting of a museum. By often using controversy and provocation, he hoped to inspire change and make society question the idea of what art was at his time. It worked well with Fountain from 1917, and it also worked with his version of Mona Lisa, to which he added a mustache and goatee and wrote a seemingly insignificant sequence of letters “L.H.O.O.Q.”

However, the caption is totally not random; it demonstrates how much Duchamp adored playing with words and conventions: if one read at loud the letters in French, they would sound like “Elle a chaud au cul”, which in rough translation means “She is hot in the arse”, or “There is fire down below”, which referred to alleged sexual restlessness of the mustached Mona Lisa. As you can imagine, in 1919 this image trespassed upon the traditional understanding of gender roles, and adding a mustache to one of the most celebrated works of art ever created was considered a sacrilege and an act of aesthetic vandalism. However, Duchamp did not really care about possible controversy, since gender reversal was his thing: he had even adopted his own female pseudonym, which again played on sexual innuendos: Rrose Sélavy, pronounced “Eros, c’est la vie”, meant “Eros, that’s life” (Eros was the god of Love).

By ridiculing the epitome of Renaissance ideals, Duchamp rebelled against everything that ‘traditional’ art stood for, in particular the appeal to harmonious and solemn beauty.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!