Zdzisław Beksiński in 10 Paintings

Zdzisław Beksiński, a visionary Polish artist, blazed an unconventional path in the world of art, leaving an indelible mark through his distinctive...

Lisa Scalone 21 February 2024

Surrealism celebrates its 100th anniversary! Since February 21, 2024, two key art institutions in Brussels have offered unmissable exhibitions. Bozar (Centre for Fine Arts) details the history of Surrealism in Belgium. At the same time, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium weave the movement’s links with Symbolism. More than 400 artworks and documents are on display—a surreal feast to celebrate what was once a revolution.

Let us start our tour with Bozar’s show, titled Histoire de ne pas rire. Surrealism in Belgium. This reminds us of the characteristics of the most important artistic movement of the 20th century in Belgium, spanning 60 years and three generations of artists. In this respect, you can imagine its footprint on this country’s collective imagination.

Unlike in France, Surrealism in Belgium survived the death of André Breton, the author of Surrealist Manifesto, and known as the so-called “Pope of Surrealism.” This independent artistic approach quickly distanced itself from Paris, in particular, by rejecting automatic writing and the role of the unconscious.

Indeed, Belgian Surrealism is first and foremost recognized for its strong sense of humor and a profound reflection on the links that unite language and image, popularized by the works of René Magritte.

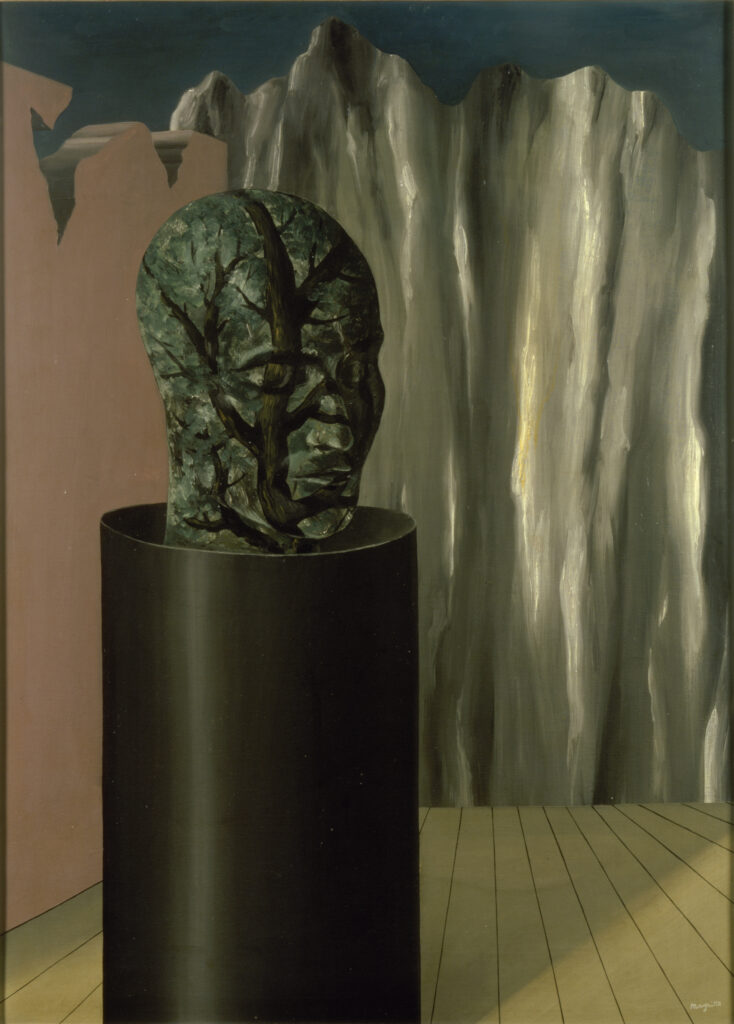

René Magritte, The Forest, 1927, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts/La Boverie, Liège, Belgium. © Succession Magritte – Sabam Belgium 2024.

In my opinion, what makes the exhibition so interesting is its willingness to highlight lesser-known artists. The relevance of their work has survived the test of time, starting with Paul Nougé, sometimes known as the “Belgium Breton,” who preferred to stay in the shadows.

The personality of this poet, theorist, and photographer is another example of the differences between Belgian and French Surrealism. The theoretician of the Belgian movement, his leadership was completely different from that of Breton.

Indeed, he had a secret personality and flourished in anonymity, which for him was synonymous with freedom. Nougé wrote extensively about Belgian Surrealism and its key principles. The name of the exhibition is the title of one of his books.

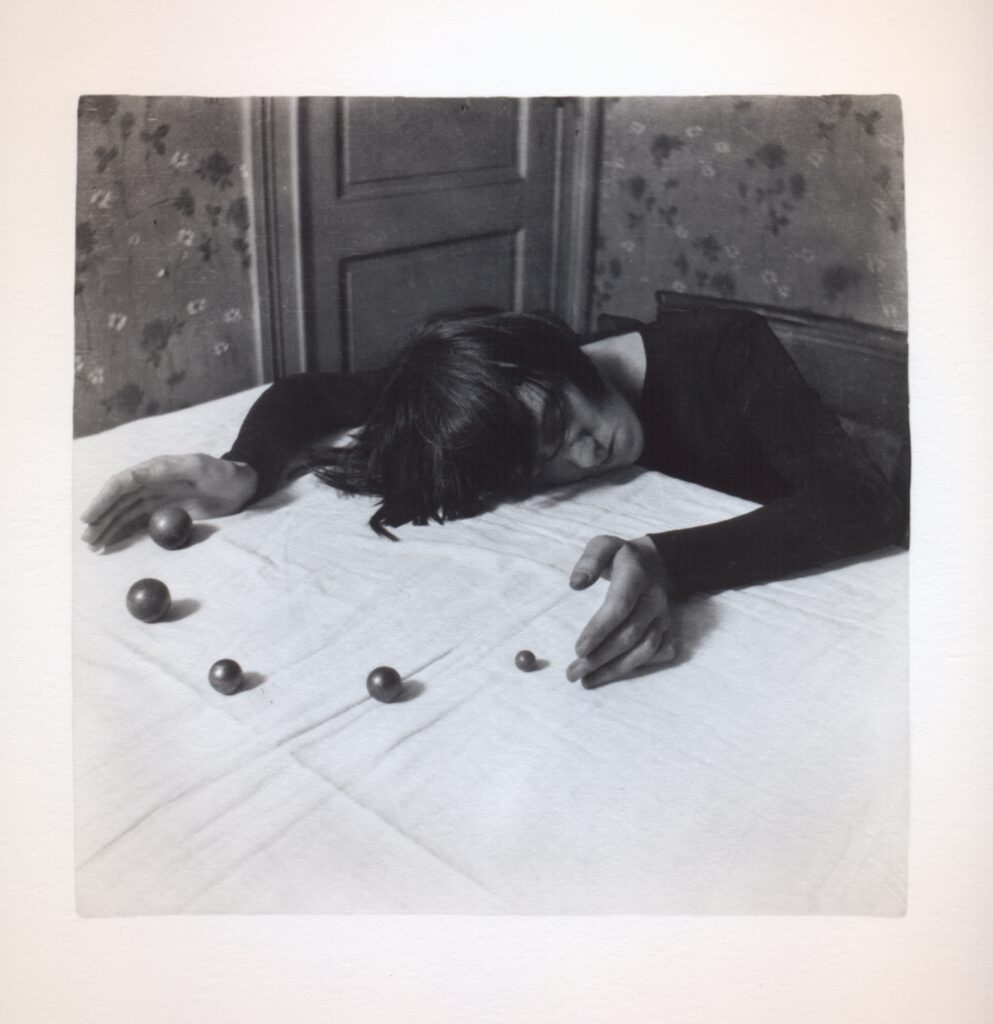

Paul Nougé, The Juggler, from the series Subversion of Images, 1929–1930, Photography, Collection Archives & Museum of Literature (AML), Brussels, Belgium. © Rights reserved.

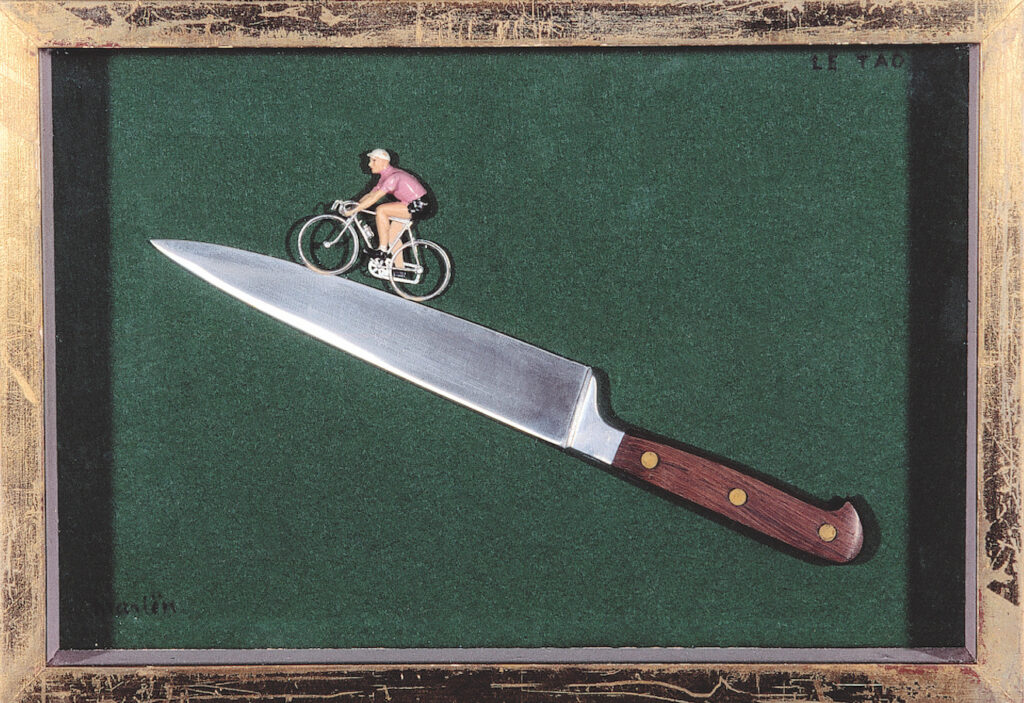

Other artists presented in the show that also attracted my attention include Marcel Mariën, Max Servais or E.L.T. Mesens. Their works show a perfect appropriation of typical Surrealist tricks such as assemblage or collage, with a dash of typical absurd Belgian humor.

Marcel Mariën, The Tao, 1976, assemblage, The Hainaut Province Collection – Deposit at BPS22, Charleroi, Belgium. © Fondation Marcel.

But the two most flagrant discoveries are undisputedly Rachel Baes and Jane Graverol, two prominent female figures of Surrealism in Belgium. Both have created a dark pictorial universe, staging the paradoxes of existence, its absurdity, and its discomfort.

Threatening landscapes, cages, or tormented characters are some of the elements used to express the anxiety of living, especially as a woman in a patriarchal world. In both cases, there is a personal decline of Surrealism that is far from the wonderful as declared by André Breton: it is no longer a matter of re-enchanting the real.

Jane Graverol, Untitled (Liberated Woman), 1949, oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm, private collection. © Sabam Belgium 2024.

It is also worth appreciating the original scenography designed by URA Architects. The works are presented on temporary walls and arranged differently in each room. The surrounding walls serve only as surfaces for texts and quotations (mainly from Paul Nougé). Consequently, walking through this exhibition is like wandering through a labyrinth, used as a metaphor for the disorientation sought by the Surrealists.

The labyrinth is precisely the theme of the first room of the exhibition of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, titled IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism. The theme refers to the Minotaur, a monster from Greek mythology, half man, half bull, locked in its Cretan labyrinth. Moreover, it’s also the name of a cult literary artistic magazine run by André Breton, famous for its cover designs by Joan Miró, Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, André Masson, and others. The maze is seen as the inner journey of the searching human being. To illustrate this idea, works by Giorgio De Chirico and Francis Picabia and a monumental sculpture by Max Ernst are on display.

The exhibition then unfolds in several rooms with its theme—night, forest, and mental landscapes. Each time, the goal is the same: confronting Surrealism and Symbolism. That is the whole challenge of this exhibition: to show how Symbolism opened the way to Surrealism. It reveals the links, similarities, and fault lines between the two movements.

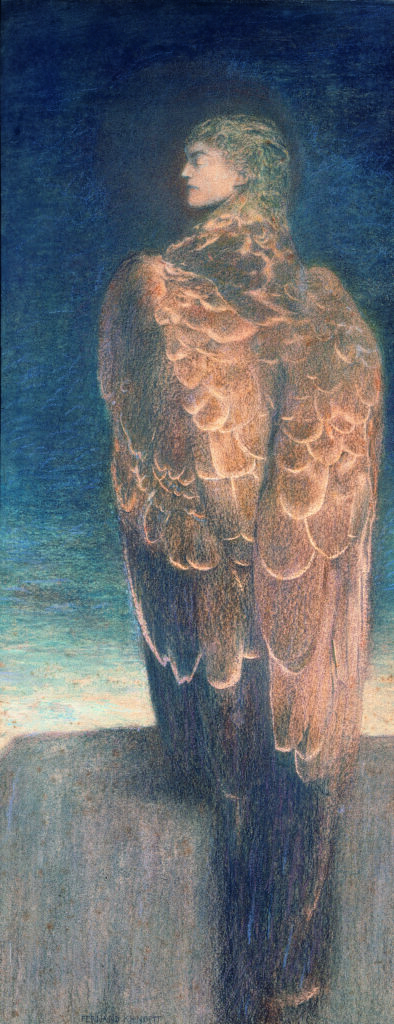

Fernand Khnopff, Sleeping Medusa, 1896, private collection.

The pioneers of Symbolism in Belgium passed on an arsenal of images, ideas, and inspiration to the next generation of Surrealists. The strange worlds of Félicien Rops, Fernand Khnopff, Jean Delville, William Degouve de Nuncques, and Léon Spilliaert, as well as the Frenchmen Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, were so inviting to explore that they sometimes became emblematic.

Curator of the Modern Art collection of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. Press release.

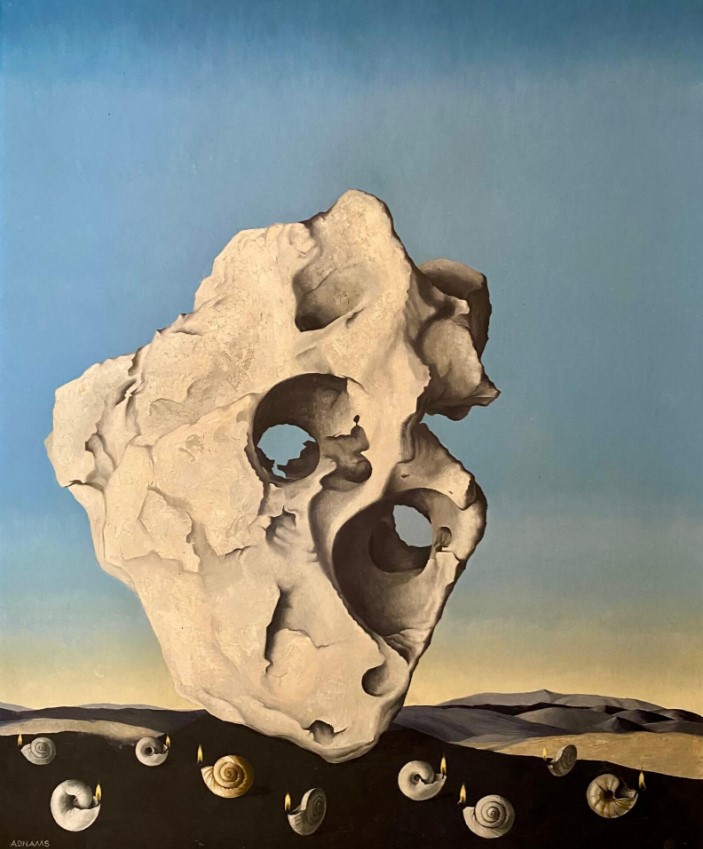

Like in Bozar, this exhibition is also an opportunity to discover many of the lesser-known artists indispensable to the Surrealist movement. For example, consider the paintings by Léonor Fini, Dorothea Tanning, Toyen, and Marion Adnams. What these artists have in common is that they produced powerful images, reflections of the universe equally as disturbing as intriguing. These works provide additional proof (but is it still necessary?) of the impressive power of the works of female surrealist artists.

Marion Adnams, A Candle of Understanding in Thine Heart, 1964, private collection.

The presence of many surrealistic objects, one of the trademarks of this movement, is also appreciated. In some ways, Surrealist objects serve as three-dimensional collages. In this case, the juxtaposed elements are found objects and cheap materials, but the principle is the same as on paper: to create an incongruous mystery. Here we see some of the most famous, such as Victor Braumer’s Wolf-Table, Le spectre du Gardénia by Marcel Jean, or Hans Bellmer’s disturbing doll.

Victor Brauner, Wolf-table, 1939–1947, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

As mentioned before, both exhibitions are an opportunity to discover many unknown artists. But don’t worry, the stars of the Surrealist movement are also present in large numbers: among others, René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, of course (don’t forget we’re in Belgium!), but also Salvador Dali, Joan Miró, Dora Maar, Man Ray and even Jackson Pollock (yes, the action-painting man had Surrealist influences in his early works)—a perfect bunch of weirdos to make an epic party. So let’s celebrate! Happy birthday, Surrealism!

Paul Delvaux, The Pink Bows, 1937, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Antwerp, Belgium.

Histoire de ne pas rire. Surrealism in Belgium is on view until June 16, 2024, at Bozar (Centre for Fine Arts), Brussels, Belgium.

IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism is on view until July 21, 2024, at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium.

Note that you can visit both exhibitions on one combined ticket. As a bonus, you can also access creative workshops (kid-friendly) at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium and an augmented reality exhibition outside Bozar.

Salvador Dalí, The Enigma of Desire, 1929, oil on canvas, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Sammlung Moderne Kunst in der Pinakothek der Moderne, München, Austria. © Sabam Belgium 2024. Photo:bpk / Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!