7 Things You Must See at the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM)

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) in Cairo, Egypt, which opened its doors on November 4, 2025, represents one of the most significant milestones in the...

Maya M. Tola 12 February 2026

1 August 2025 min Read

The National Museum in Warsaw is one of the most important museums in Poland. It also has an amazing collection of art—which, obviously, includes a collection of Polish art. We have highlighted ten Polish paintings from the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw that you need to know. If you ever travel to Warsaw, don’t forget to visit the museum!

I have a confession to make. I was born in Warsaw, and when I was growing up and studying art history in high school, the National Museum in Warsaw was my number one museum. So, I’m quite emotionally attached to it. The hours I spent there had something to do with starting DailyArt years later. But anyway, you will see for yourself that what hangs on its walls definitely deserves wider recognition—both within and outside Poland.

This work is a masterpiece of Polish Academic painting. It depicts a love drama featuring a noblewoman, Barbara Radziwiłł, and Sigismund II Augustus, the last king of Poland and a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty. The couple fell in love, but, unfortunately, she wasn’t a royal and therefore not a suitable match for the king.

In 1547, Sigismund married her in secret and this sparked a scandal. Popular opinion saw the union as a misalliance and an affront to the state of Poland. Only after a long struggle with his mother and parliament did Sigismund manage to bring about Barbara’s coronation in 1550. Six months after the coronation, Radziwiłł suddenly died. Gossip said it was Sigismund’s mother, Queen Bona, who poisoned the poor woman.

Józef Simmler chose to paint the moment of the young queen’s death. The end of her life is symbolized by the censer on the floor and the closed prayer book on the chair. The only suggestion of regal splendour is the bedspread lined in ermine fur. The painting was exhibited in 1860 to tremendous acclaim, solidifying Simmler as a leading artist of his day. Its success lay not solely in its subject but also in its artistic quality, the understated colors, and the perfectly rendered details.

Chełmoński was a painter of the Realist school. This is an early work produced shortly after the artist’s return to Warsaw from the art academy in Munich. Chełmoński’s intention in Indian Summer was to depict the vitality of the countryside and the fortitude of its people.

In the centre of the composition is a country girl dressed in a typical Ukrainian costume. (Ukraine used to be part of Poland from 1569 to 1772) . She is lying stretched out in the middle of a pasture. In the background, we can see a black dog sitting nearby, watching over the herd with his back to the viewer. It is the dog’s diligence that allows the girl to get swept away in her thoughts and wallow in her memories of the fleeting summer. The warm sun drenches the dry grass, and the cloudless sky evokes the tranquility of a September afternoon. The artist had been fascinated with Ukraine from childhood, visiting it on numerous occasions in search of nature untarnished by man.

The critics didn’t like the painting. Why should a peasant girl with dirty feet, sprawled out in a field, grace the wall of a sitting room or museum? This critical response hastened the artist’s decision to relocate to Paris, where he would live and work for the next 12 years. Chełmoński’s rural scenes of the Polish borderlands, all painted from memory, found appreciation in Paris and brought him great financial success.

This is the most famous painting in Poland, the number one highlight from the National Museum’s collection. It shows a scene from Polish history—the great victory of the allied Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania over the Teutonic Order in 1410. This monumental painting (426 × 987 cm; 168 in. × 389 in.), created in 1878, was meant to uplift the spirits of the Polish people during a time when their country had been partitioned and no longer existed as an independent state. This is why it is still so deeply rooted in Polish collective memory.

The painting’s composition is very complex. When you stand in front of it, you may feel as if the whole painting is about to collapse on you. You feel as if you are at the center of the battle. Jan Matejko said he felt like a “possessed man” while making this masterpiece. A French critic, upon seeing the painting in Paris in 1879, remarked that it was a museum in itself—so rich in detail that it demanded eight full days of study to be truly appreciated.

Meanwhile, other critics highlighted the battle’s unrealistic portrayal and noted several historical inaccuracies. Some also found fault with the composition, describing it as overly crowded and chaotic. As I’m not a great admirer of this painting myself, I will also show you the caricature created by another famous Polish artist from the same epoch, Stanisław Wyspiański. I think I share his feelings towards this work.

During World War II, this painting was stolen by German forces and was only recovered in 2011. Since that time, it has become one of the symbols of the National Museum in Warsaw.

The painting shows a Jewish shopkeeper. She wears simple, worn clothing, with a scarf resting loosely on her shoulders. In her hands, she carries two baskets brimming with oranges. Behind her, the rooftops of Warsaw stretch into the distance. Her face is marked by fatigue and hardship, with a solemn expression that conveys both exhaustion and a quiet sense of despair. In contrast, the vivid color of the oranges conveys a feeling of vitality, warmth, and the atmosphere of the South.

Aleksander Gierymski’s work was representative of Realism as well as an important precursor of Impressionism in Poland. Like Courbet, he often represented the lives of humble people. Tragically, the last years of his life were spent in a mental hospital.

Olga Boznańska’s painting In the Orangery (In the Greenhouse) portrays a young girl standing in a greenhouse, surrounded by lush greenery and blooming potted flowers. Her posture and expression convey a quiet tension—she seems both curious and slightly uneasy, as if aware of someone who has just entered the space. Her gaze is directed at the viewer, subtly pulling us into the scene.

This is one of the most important works from Boznańska’s Munich period. Whilst studying there, as well as later when she became independent as an artist, she often portrayed her friends. She was only 25 years old when this painting was created! Adolescence was the main subject of her art and was closely linked with the rise of the Symbolism movement in poetry. Boznańska’s painting refers to one of the most-talked about collections of poems from that time, Maurice Maeterlinck’s Les serres chaudes.

Later in her life, Boznańska lived in Paris, where her art was greatly influenced by the paintings of James McNeill Whistler, Édouard Manet, and Wilhelm Leibl, artists who combined Realism with Impressionism.

Strange Garden is one of the most exquisite and mysterious works in the history of Polish painting. It is an extraordinary mix of reality and colorful fiction.

Mehoffer painted this masterpiece during a family holiday, which he spent in the countryside with his wife and son. In an orchard filled with old apple trees bursting with gold-tinted fruit, a naked boy stands on blossoming foliage whilst holding long stalks of blooming hollyhocks. Next to him we see Mrs. Mehoffer, reaching for an apple in an elegant sapphire-blue dress (designed by Mehoffer himself). In the background, a nanny in traditional costume extends her hand towards garlands of flowers hanging from the trees.

But the most remarkable element of this painting is the giant dragonfly. Its wings resemble pieces of colored glass in black lead frames. The dragonfly was often interpreted as a symbol of vanitas or as an allusion to the three stages in the development cycle of an insect. However, such hypotheses find no confirmation in the writings of the artist himself. To Mehoffer, the dragonfly stood for the sun. This brings us back to the notion of an idyll in which the tall flowers held by the child and the light flooding his figure suggest fatherly pride and aspirations

Wojtkiewicz was a Polish painter, illustrator, and printmaker. Although generally considered an Expressionist, some of his works are precursors of Surrealism.

When we look at this painting, we may think that we are looking at an illustration of a fairy tale. But this scene is not an illustration of any known fairy tale. We see a little boy who is escaping with a princess on a wooden horse. In the background, we see an old woman and an old man with crutches, who probably want to rescue the princess. The whole scene is quite disturbing, and we seem to be witnessing a dreamlike drama. How does the story end? Were the boy and the girl happy together?

Wojtkiewicz was suffering from an incurable, congenital heart defect, and this painting was created just before his premature death at the age of 29.

Witkiewicz, commonly known as Witkacy, was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer. He was active before World War I and during the interwar period.

After 1925, the artist satirically rebranded his portrait work—which provided his main source of income—as “The S.I. Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Company,” complete with the motto: “The customer must always be satisfied.” He offered a range of portrait types, varying from straightforward, representational likenesses to more experimental, expressionistic versions. The latter were often created under the influence of various substances and came at a higher price. In fact, many of his paintings included handwritten notes listing the specific drugs—sometimes just a cup of coffee—consumed during their creation.

Witkacy created the theory of Pure Form, the ideals of which he implemented in this painting, where form is more important than the content of the work. Upon learning of the Soviet invasion of Poland on September 17, 1939, Witkacy took his own life the following day by overdosing on drugs and attempting to slit his wrists.

Yes, Tamara de Lempicka, one of the most important artists of Art Deco, was Polish. In this article we just had to mention her! Lempicka’s style, was a blend of late, refined Cubism and Neoclassicism. She was an active participant in the artistic and social life of Paris between the wars and became famous as a result of her portraits and nudes.

She developed a very recognizable style, using luminous and brilliant colors which reflected the elegance of her models. Lempicka placed a high value on working to produce her own fortune. She famously said: “There are no miracles; there is only what you make”. She used her personal success to live a hedonistic lifestyle, one that included several intense love affairs.

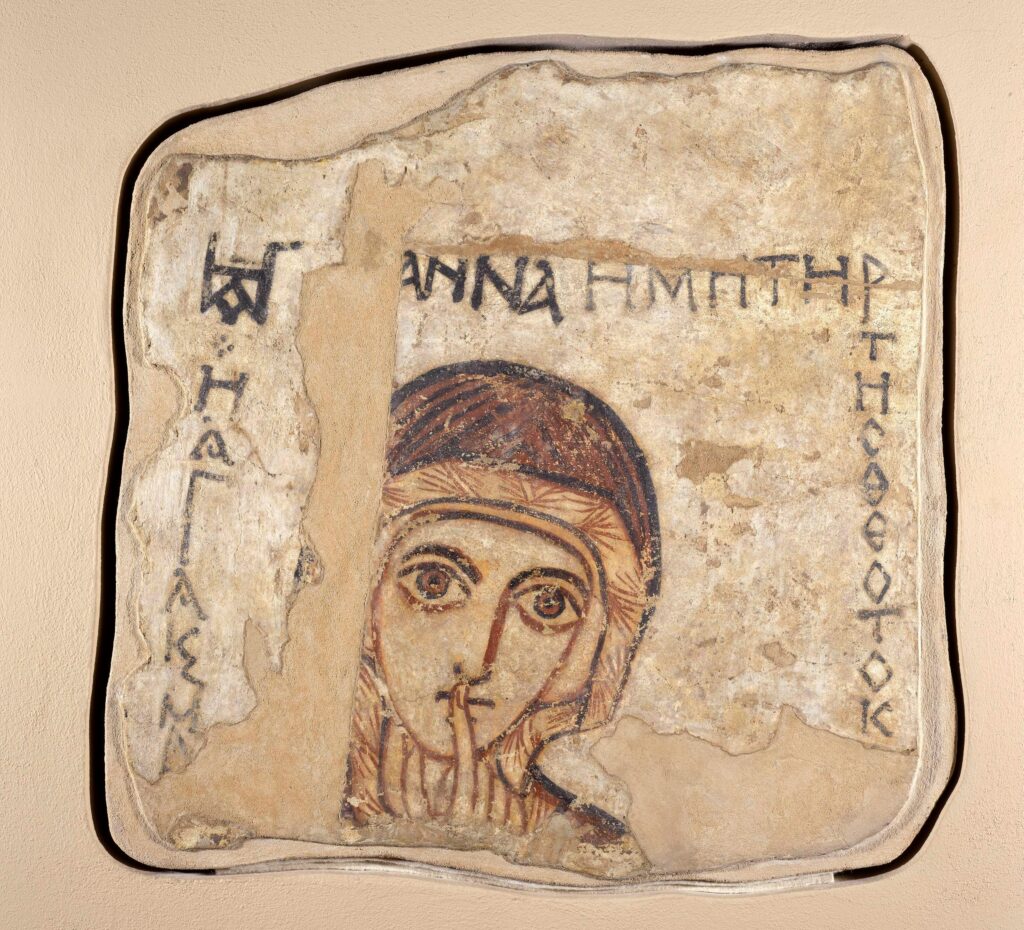

Time for the last highlight of the National Museum in Warsaw. I know this is not Polish art but it is something you need to see if you ever visit the museum. This fresco is one of many Makurian wall paintings estimated to have been created between the 8th and 9th centuries. It was painted al secco with tempera on plaster and was found at the Faras Cathedral within old Nubia in present-day Sudan. The frescoes show scenes from the Old and New Testament as well as portraits of local dignitaries.

A Polish archaeological team discovered the frescoes in Faras during a 1960s campaign under the patronage of UNESCO (the Nubian Campaign). They are absolutely unique and extremely well preserved.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!