Peter Paul Rubens in 10 Paintings

A Baroque master and portraitist of the royals, Peter Paul Rubens is probably best known for his often drama-filled religious and mythological...

Anna Ingram 30 May 2024

Johannes Vermeer is one of European art’s most loved and mysterious painters. Moderately known during his lifetime, completely forgotten after his death until the 19th century, he is now one of the brightest stars of the Dutch Golden Age. Only around 35 masterpieces are now attributed to him. In most, we can spot the same everyday objects, jewelry, and interior decoration items. Among them are the paintings with Cupid, executed by Vermeer four times as a painting-within-a-painting—each time a little differently. What was his secret?

This story is based on the research done in preparation for the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden exhibition Johannes Vermeer. On Reflection presented in 2021. That year, Dresden, the capital of Saxony in Germany, became the principal place to be for all Vermeer lovers. The exhibition, presented in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD), collected 10 Vermeer paintings from around the world, accompanied by a selection of 50 works of Dutch genre painting that illustrate relationships and interactions between the works of Vermeer and his contemporary artist colleagues. 10 of the around 35 paintings are attributed to him—that was a real treat!

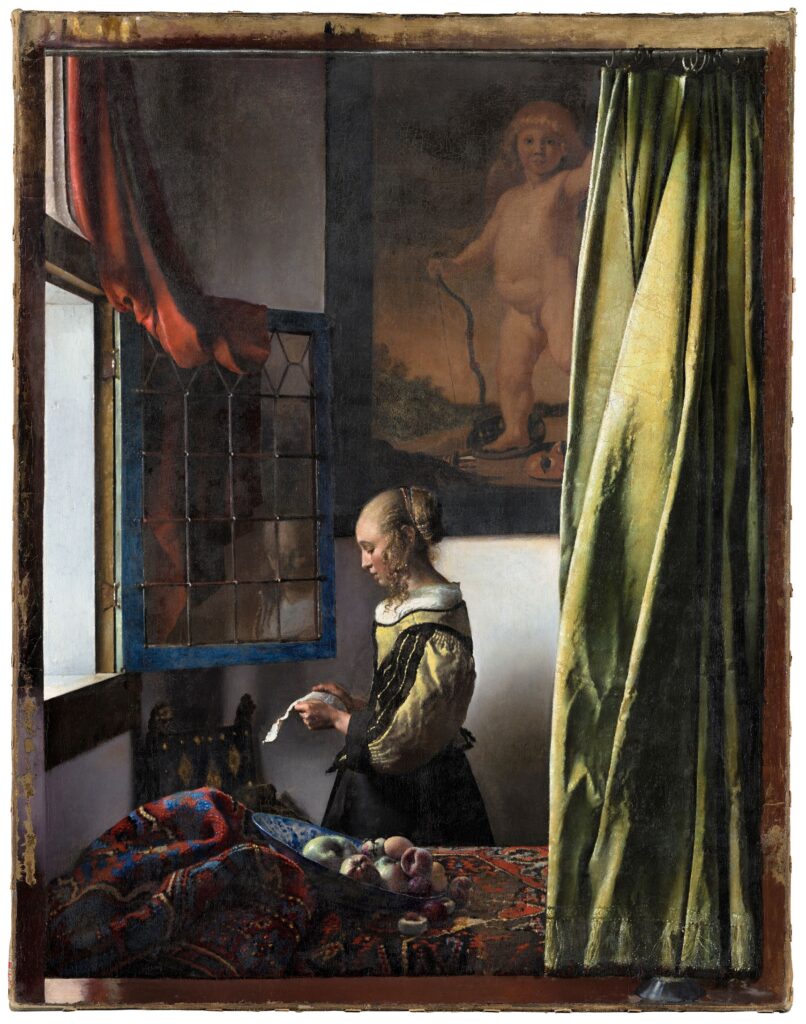

But the jewel in the crown was this one—a recently renovated Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window from SKD’s collection. Thanks to x-ray analysis, it was known from 1979 that it had an overpainted figure of Cupid on the wall in the background. In 2021, the restorers brought the little god of desire, erotic love, attraction, and affection for daylight.

The painting before conservation, with the overpainted background, © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Photo by Jürgen Lange.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, after the restoration, c. 1657–1659, © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Photo by Wolfgang Kreische.

The painting-within-a-painting of Cupid was covered for unknown reasons in the 18th century. The museum conservationists cleaned the painting and removed the overpainted layers. You can read more about the whole process here. As a result, the painting now looks like it was finished by the artist yesterday, which made art historians rethink how Vermeer’s masterpiece should be interpreted.

Cupid, the naked blond-haired god of love, is holding a bow in his right hand and gazing out at the viewer from the picture on the wall, enclosed by a thick black frame. Arrows are lying on the ground, and the god of love is treading on the masks before him. His left side is covered by green drapery.

Without Cupid, the painting showed a beautiful girl standing by the window, focused on reading a letter. With him, we can say one important thing—love is in the air (or, to be more exact, on the wall). Vermeer makes a fundamental statement on the nature of true love beyond the superficial romantic context through this little god.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1657–1659, © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Photo by Wolfgang Kreische. Detail.

In the artist’s oeuvre, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window marks the beginning of a series in which individuals, usually women, pause during an activity to find a moment of calmness and to reflect. Through details, this painting is directly linked to three other masterpieces. The Delft artist changed the display and number of elements in them, but they all have one constant—the figure of Cupid himself.

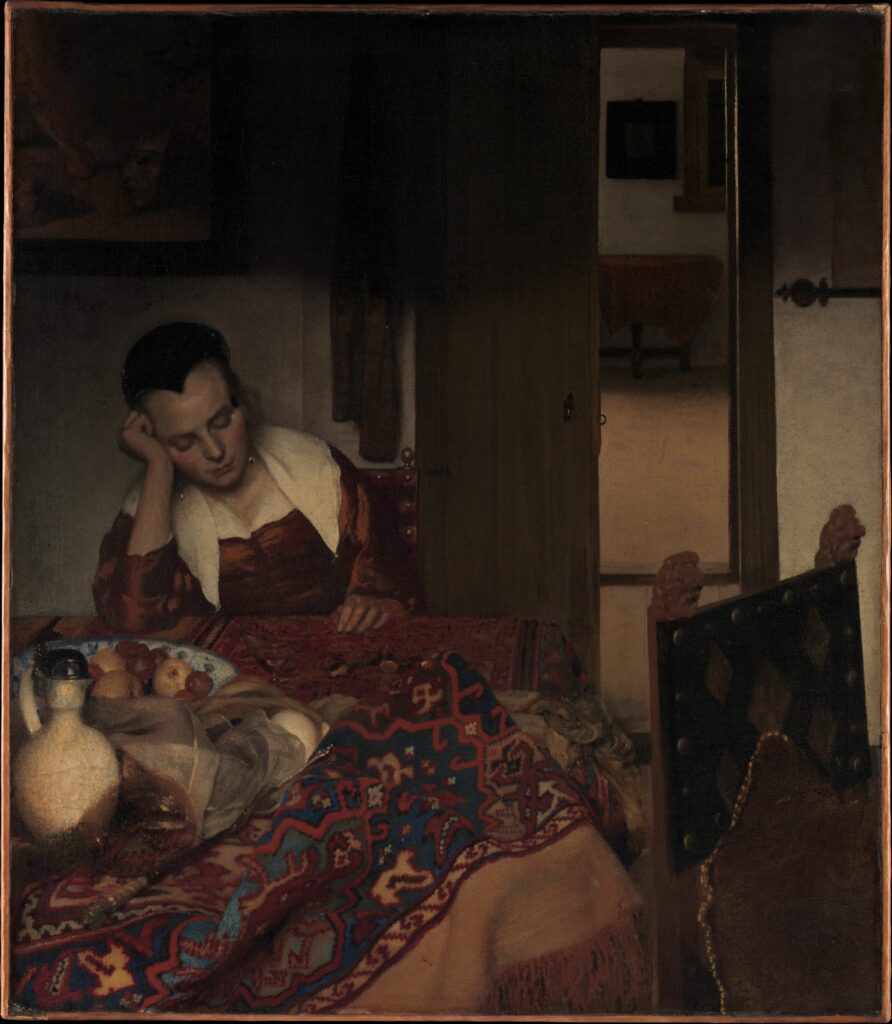

Johannes Vermeer, A Maid Asleep, c. 1656–1657, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Around 1656–1657, Vermeer included a similar Cupid painting in his A Maid Asleep (from The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection). In the upper left corner of the painting, hidden in a dark shadow, we see a small part of the painting hanging on the wall. To be exact, we only see someone’s legs and a mask—very similar to what we see in the Dresden paintings.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Interrupted at her Music, c. 1658–1659, The Frick Collection, New York City, © The Frick Collection. Photo by Michael Bodycomb.

The painting of Cupid appears again in Vermeer’s Girl Interrupted at her Music, dated around 1658–1659. As in the Dresden masterpiece, the picture of Cupid was once overpainted, but these add-ons were removed in 1907. Unfortunately, not much more can be said about the painting-within-a-painting because of the poor state of the work’s preservation. We can trace a bow and maybe some arrows, but whether the masks were included is now impossible to say.

Johannes Vermeer, Lady Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670–1672, © The National Gallery, London, UK.

Ten years later, around 1670–1672, Vermeer used the painting of the cupid for the last known time in his work Lady Standing at a Virginal. Here, Cupid is portrayed in full, in the same pose as in Dresden, except for his right leg, which gives the impression of movement. In this painting, Cupid’s left hand is finally visible—he holds a playing card—or a letter—something white and small. We will come back to this motif later.

Using the same painting in four works led to speculations that it was based on an actual painting that the artist owned. In all four Vermeer masterpieces, the painting-within-a-painting was depicted similarly. As Cupid was reproduced over a period of about 15 years, it is difficult to talk about any coincidence—especially since we know that the inventory of Vermeer’s estate, compiled after his death in 1676, mentions an artifact “from the upstairs backroom” referred to as “Cupid,” which could be this painting.

Art historians tried to track it in the vast history of auctions and sales of works of art, but it proved impossible to find. Interestingly, based on Vermeer canvases, they tried to estimate the size of the actual Cupid painting—it should be about 115 x 85 cm (45.3 x 33.5 in), so it is pretty large (bigger than most of the scenes painted by Vermeer).

Another question is, who could be the author of the lost Cupid? Art historians try to link it with the name of Caesar van Everdingen, a Dutch Golden Age portrait and history painter who painted numerous depictions of similarly proportioned naked putti (nude child figures, often with wings). What can be said for sure is that the painted Cupid belongs to the pictorial tradition of portraying a full-figure, life-size Cupid alone, combined with symbolic gestures and motifs.

Other great painters from this time made this motif quite popular. Rembrandt painted Cupid blowing a bubble in 1634. The little god of love was also often presented with a golden balance, a pair of scales, and, of course, wings.

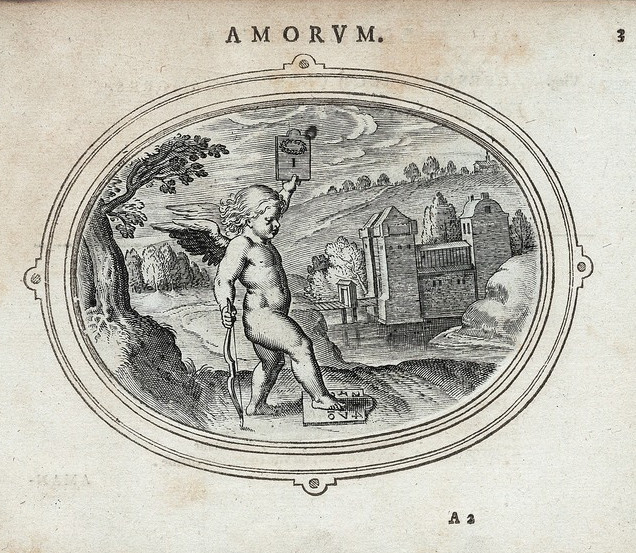

Cornelis Boel, Unshakeable Faith, emblem from Otto van Veen, Amorum emblemata, Antwerp 1608.

What really increased Cupid’s popularity in the arts was his appearance in a series of emblem books in the first quarter of the 17th century. These books presented a visual depiction (icon) with a short caption (lemma) and explanatory text or verse (epigram). For example, Cupid from a 1601 publication consisted of a verse: “You ask what love is” (it seems like the painting from Vermeer’s paintings answers this question).

The emblems may explain other elements from the Cupid paintings. Otto van Veen’s Amorum emblemata is not only the largest but, from a European point of view, is also the most influential collection of love poems ever published in 1608. The mask thrown to the ground and shattered signifies the contempt for deception and the duality of human nature. For this reason, Cupid tramples the mask as a sign of deception to emphasize that the love is sincere and candid.

Cornelis Boel, Perfect love is only for one, emblem from Otto van Veen, Amorum emblemata, Antwerp 1608.

Another symbol is the thing held by Cupid in the Lady Standing at a Virginal. Some recognize it as a card, but it is linked to the emblem by Otto van Veen, which shows Cupid in a landscape, holding a tablet with the number one on it, topped by a crown of laurels. It would mean that there is only one real love.

Cornelis Boel, In the letter we see those absent, emblem from Otto van Veen, Amorum emblemata, Antwerp 1608.

Another interpretation says it is not a card but a folded and sealed letter, a common theme in Vermeer’s works. It makes sense because letter writing was a vital and thriving cultural activity during his lifetime (for romance as well). Another emblem by Veen speaks for this interpretation: entitled “In the letter, we see those absent,” meaning that no matter how far away our loved one is, we can see and speak with them through the written word. With this explanation, Cupid would also be a messenger of love.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1657–1659, © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Photo by Wolfgang Kreische. Detail.

Finally, after the restoration, the Dresden painting makes a clear statement: it is a love scene. We look at a girl reading a love letter—or a letter from someone she loves. A husband or a lover? Is the news positive for her? Is she waiting to unite with this person? We can’t tell. Vermeer doesn’t give us any suggestions. The girl’s face is focused but emotionless.

The revealed Cupid is not a silent witness to the scene, though. He is an active member. By taking action and trampling over the mask, he shows the true face of love, decent, and faithfulness. He is showing us the right choice. This suggests that everything finished well in this story.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!