Anna Ancher in 10 Paintings: Capturing Light

Anna Ancher, a local born and bred, became one of the leading artists of the Danish town of Skagen. She knew and painted her family, the inhabitants,...

Catriona Miller 29 January 2026

When World War I left thousands of soldiers with faces they could no longer recognize, one sculptor decided to help them face the world again. Anna Coleman Ladd, an American artist in Paris, used copper, plaster, and paint to rebuild not only their appearance but also their sense of humanity.

The Great War was unlike any conflict before it. Machine guns and shellfire left millions wounded and thousands disfigured beyond recognition. Surgeons did their best, but medicine could not keep pace with the devastation of industrial warfare. Around hospitals, some benches were painted blue to warn passersby that the men sitting there might be too distressing to see. Mirrors were removed from wards so patients would not collapse at the sight of themselves, and many refused to leave their rooms at all.

It was in this atmosphere of isolation and shame that Ladd’s idea took shape, a belief that art could restore the dignity that war had stolen.

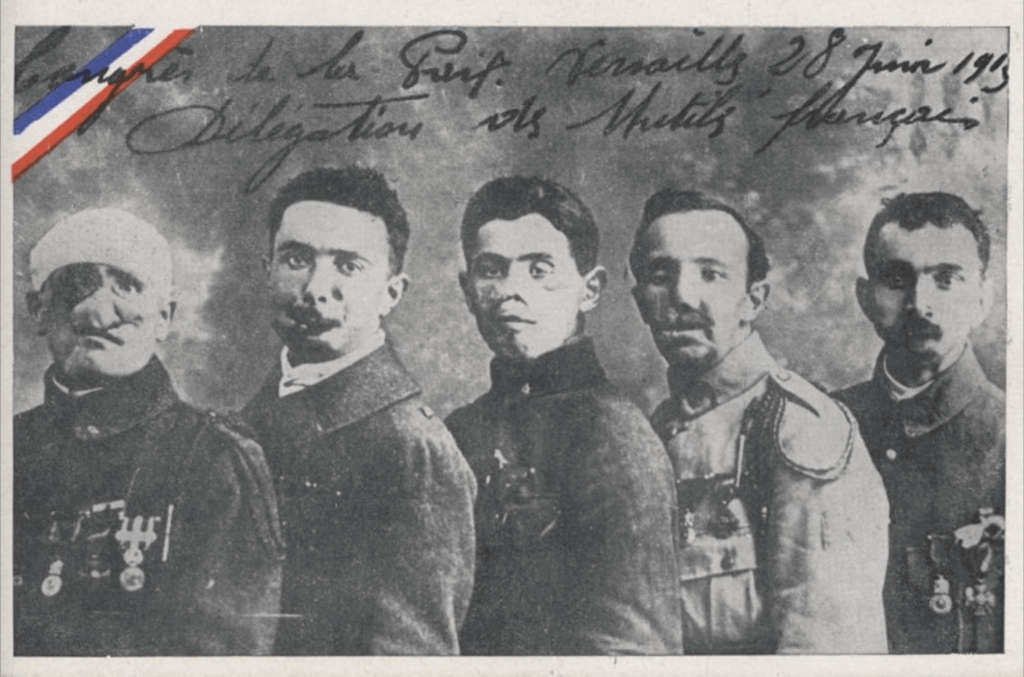

Delegation of Wounded French Soldiers, Peace Congress, Versailles, June 28, 1919, Paris Interuniversity Library of Health,

Paris Cité University, Paris, France. University’s website.

Anna Coleman Ladd was born in Pennsylvania in 1878. She was a self-taught sculptor who bypassed formal training at art academies, instead creating her works through drawing and modeling from life. Before the war, Ladd sculpted joyful fountains and portrait busts in Boston. But in 1917, after learning that wounded soldiers in London were receiving lifelike metal masks, Ladd realized her art could serve another purpose. When her husband was appointed Deputy Commissioner of the Children’s Bureau of the American Red Cross in Toulouse, Ladd followed him to Paris and established the Studio for Portrait Masks.

The studio at 70 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs was bright and full of flowers, with shelves lined with plaster casts. Soldiers arrived quietly after surgeries that ensured survival but not their appearance.

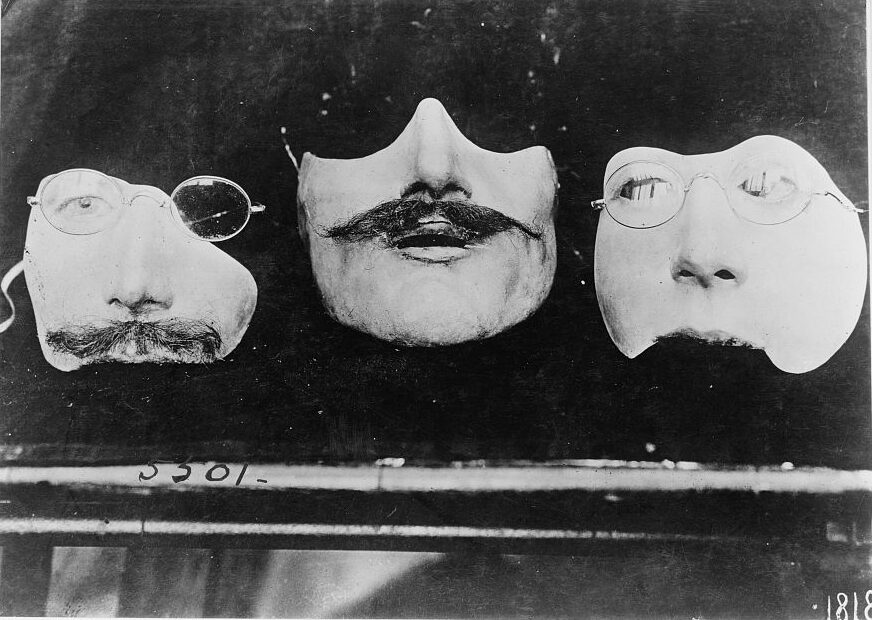

Masks showing different stages of work: casts taken from the soldiers’ mutilated faces; the lower row shows the faces modeled on the foundation of the life mask. On the table rest some of the final masks made to fit over the disfigured part of the face. France, 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

Our work begins when the surgeon has finished… A mask that did not look like the individual as he was known to his relatives would be almost as bad as the disfigurement.

J. Kedey, “Masks for the Maimed,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 5, 1918, p. 3.

Ladd approached each face not as a wound, but as a person. First, she made a life cast of the soldier’s features using plaster. From this fragile mold, Ladd sculpted a new visage in clay, restoring lost symmetry, smoothing torn skin, and imagining what had once been.

Anna Coleman Ladd, Three masks made for men with facial mutilations, France, 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

She then hammered thin sheets of copper into shape, building the prosthetic like a second skin. Painted with enamel and matched to the soldier’s exact eye and hair color, each mask was finished with real eyelashes and mustache hairs. Every detail was an act of care. When the work was done, Ladd handed the soldiers not just a mask but a mirror.

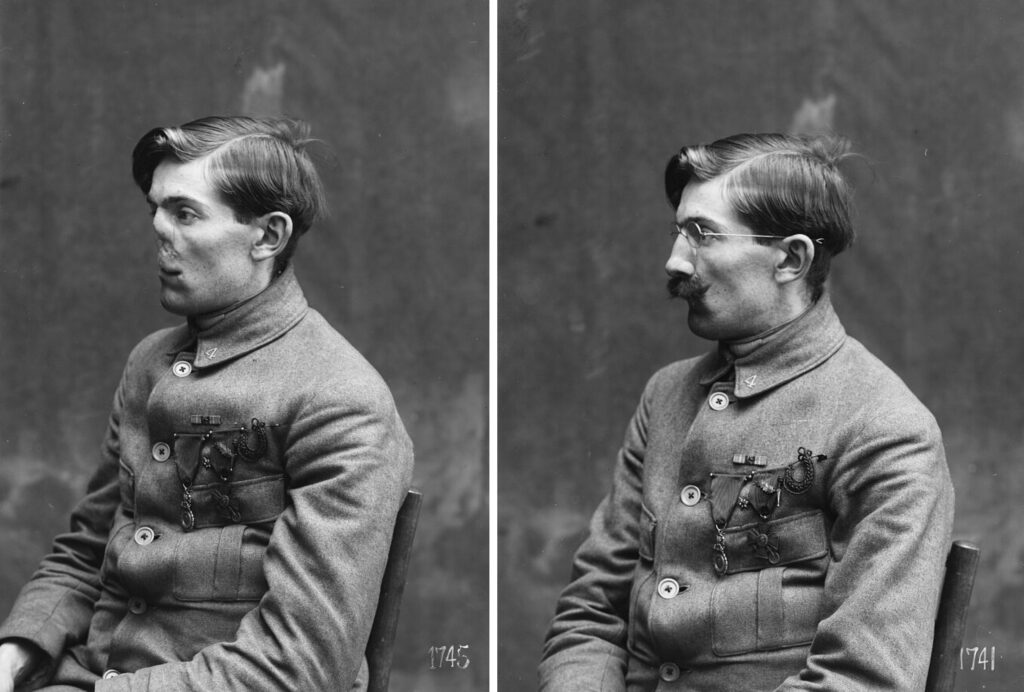

Anna Coleman Ladd and a soldier fitting one of her masks covering middle part of his face, France, 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

Ladd’s masks were not just prosthetics; they were portraits. Each one carried the artist’s tenderness, a silent promise that even a broken face deserved beauty. For men once called mutilés (the disfigured), the masks offered more than form: they offered a way back into the world.

Thanks to you, I was able to go out without attracting stares… You gave me back the face my mother remembers.

Knowlton Mixer, “Bureau of Portrait Masks,” Report for the Department of General Relief, August 1919, pp. 12-13. Hoover Institution Library & Archives, xx482 bx76 fl23.

By the end of 1918, Ladd and her small team had created over one hundred masks. The number may seem small beside the war’s devastation, but the impact was immense. Ladd didn’t just sculpt copper. She sculpted courage.

French soldier fitting a mask by Anna Coleman Ladd (view before and after), 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

Long before the term “anaplastology” entered medical vocabulary, Anna Coleman Ladd was reshaping what healing could mean. While surgeons worked with scalpels and stitches, she approached each wounded face with an artist’s eye, for proportion, color, and above all, for dignity. Her masks did not aim to erase the past but to help survivors be seen again as whole and human.

Anna Coleman Ladd saying goodbye to a blind soldier, France, 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

What made Ladd’s studio so rare was not only the craftsmanship but also the quiet understanding that healing required more than surgery. She did not see herself as a medical pioneer. Her purpose was more intimate: to restore a sense of self to those the world had turned away from. In this, Ladd’s work planted the earliest seeds of a field where art meets medicine and where compassion becomes its own kind of cure.

Ladd seated in the foreground, surrounded by her patients at her studio, Christmas Day, France, 1918, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

After working tirelessly in Paris for nearly a year, Ladd returned to Massachusetts in December 1918. She had completed 67 masks by then, each a quiet act of restoration, and left behind a studio still staffed with artists and supported by the Red Cross. Though officials urged her to open a similar studio in America, Ladd declined. She had seen too much. Her husband resumed his medical practice, and she returned to sculpture, not of prosthetics, but of fountains, symbolic reliefs, and commemorative memorials.

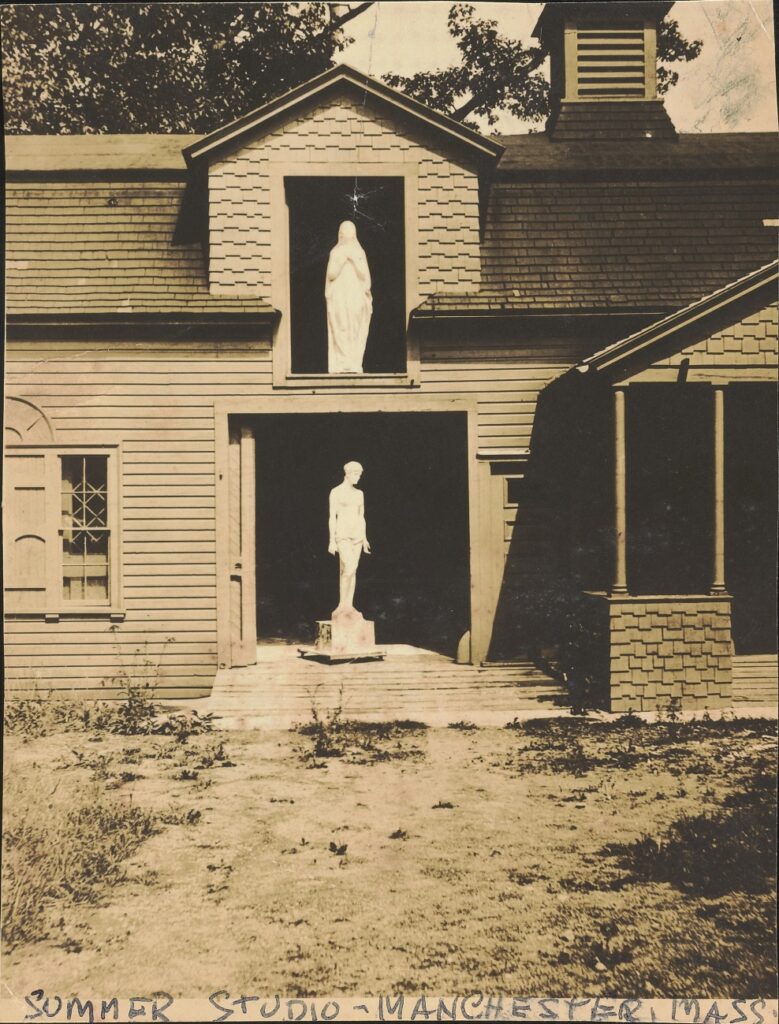

Ladd’s “Arden” summer studio in Manchester, Massachusetts, 1910, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, USA. Archive’s website.

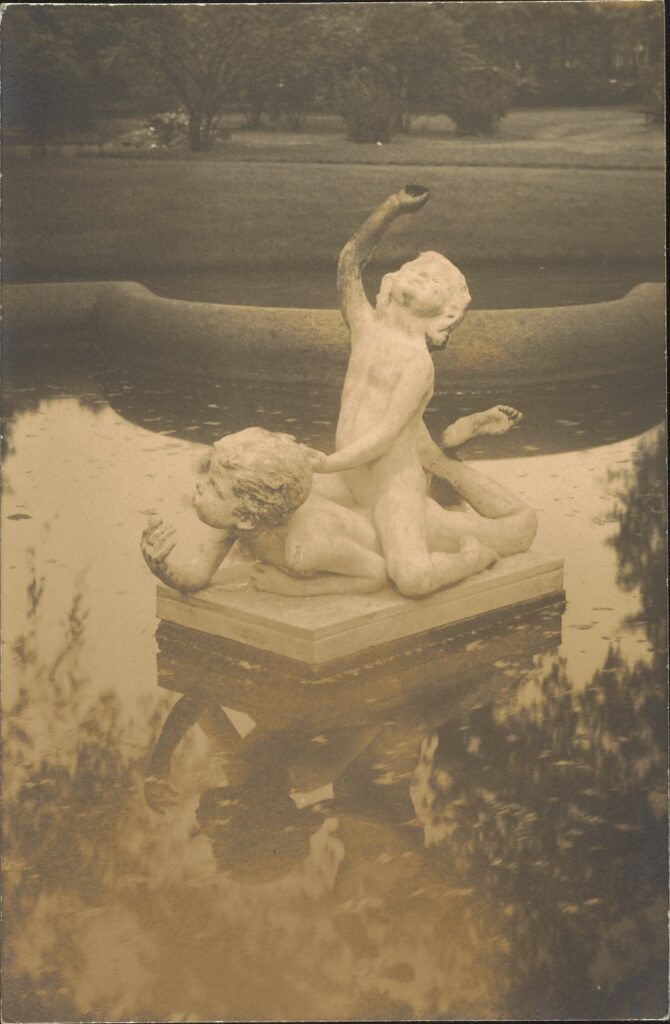

Back in Boston and Beverly Farms, in the quiet studio she called “Arden”, Ladd’s work shifted: the lighthearted bronzes of her early career gave way to portrait busts, memorial tablets, and public commissions shaped by memory and loss. Among them were war memorials designed for communities and veterans’ groups, solemn tributes that bore neither triumph nor sentimentality, only a quiet reverence for survival. One of Ladd’s few joyful creations, Triton Babies, recalled the innocence of an earlier world untouched by war.

Anna Coleman Ladd, Triton Babies fountain, 1922, Archives of American Art, Washinton, DC, USA. Archive’s website.

France later honored Ladd with the Légion d’Honneur for her service to the wounded. Yet her true legacy lived not in medals or monuments, but in the restored faces—and restored lives—of the men who once sat before her in silence.

Anna Coleman Ladd with bust, showing her war medals, 1930, Archives of American Art, Washinton, DC, USA. Archive’s website.

As November brings Veterans Day, a moment of gratitude for those who served, Ladd’s story reminds us that remembrance is not only about the fallen. It is also about those who came home, bearing visible and invisible wounds, and the people who helped them heal.

Anna Coleman Ladd’s art remains a quiet salute to humanity itself.

Anna Coleman Ladd, 1919, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. Library’s website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!