Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

27 June 2022 min Read

Théodore Géricault completed The Raft of the Medusa when he was 27, and the work has become an icon of French Romanticism. It is a direct precursor of Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios and Liberty Leading the People.

In fact, Delacroix himself modeled for The Raft as the foreground figure lying face down with his arm stretched toward the viewer. Delacroix wrote

Géricault allowed me to see his Raft of Medusa while he was still working on it. It made so tremendous an impression on me that when I came out of the studio I started running like a madman and did not stop till I reached my own room.

Éugene Delacroix, diaries of the artist.

It is 16 ft x 21.5 ft (491 cm × 716 cm), the figures are larger than life-size, and it dominates the room in the Louvre where it is housed. It depicts a moment from the aftermath of the wreck of the French naval frigate Méduse, which ran aground off the coast of today’s Mauritania on 2 July 1816. On July 5, 1816, at least 147 people were set adrift on a hurriedly constructed raft; all but 15 died in the 13 days before their rescue, and those who survived endured starvation and dehydration and practiced cannibalism. The event became an international scandal, in part because its cause was widely attributed to the incompetence of the French captain.

Géricault chose to depict this event to launch his career with a large-scale uncommissioned work on a subject that had already generated great public interest. The event fascinated him, and before he began work on the final painting, he interviewed two of the survivors and constructed a detailed scale model of the raft. As he had anticipated, the painting proved highly controversial at its first appearance in the 1819 Paris Salon, attracting passionate praise and condemnation in equal measure. It established his international reputation and is widely seen as seminal in the early history of the Romantic movement in French painting.

The dramatic presentation and subject represent a break from the calm and order of the prevailing Neoclassical school. Géricault’s work attracted wide attention from its first showing and was then exhibited in London. The Louvre acquired it soon after the artist’s death at the age of 32. The painting’s influence can be seen in the works of Eugène Delacroix, J. M. W. Turner, Gustave Courbet, and Édouard Manet.

In June 1816, the French frigate Méduse departed from Rochefort, bound for the Senegalese port of Saint-Louis, with Viscount Hugues Duroy de Chaumereys as captain, despite having scarcely sailed in 20 years. It ran aground on a sandbank off the West African coast, near today’s Mauritania, after drifting 100 miles (161 km) off-court because of poor navigation. On July 5, the frightened passengers and crew started an attempt to travel the 60 miles (97 km) to the African coast in the frigate’s six boats, but as with the Titanic, there was not enough room in the lifeboats for everyone on board.

At least 146 men and one woman were piled onto a hastily built raft, which partially submerged once it was loaded. The captain and crew aboard the other boats intended to tow the raft, but after only a few miles the raft was turned loose. For sustenance, the crew of the raft had only a bag of ship’s biscuits (consumed on the first day), two casks of water (lost overboard during fighting), and six casks of wine.

According to critic Jonathan Miles, the raft carried the survivors “to the frontiers of human experience. Crazed, parched and starved, they slaughtered mutineers, ate their dead companions and killed the weakest.” On July 17, the raft was rescued by the Argus by chance, no search effort having been made by the French, but by this time, only 15 men were still alive. The others had been killed or thrown overboard by their comrades, died of starvation, or thrown themselves into the sea in despair. After the wreck, public outrage mistakenly attributed responsibility for his appointment to Louis XVIII, and the incident became a huge public embarrassment for the French monarchy, only recently restored to power after Napoleon’s defeat in 1815.

The Raft of the Medusa portrays the moment when, after 13 days adrift, the remaining 15 survivors view a ship approaching from a distance. According to an early British reviewer, the work is set at a moment when “the ruin of the raft may be said to be complete.” Because the painting is so monumental, the giant figures are pushed close to the picture plane and are crowding onto the viewer, who is drawn into the physical activity as a participant.

The makeshift raft is shown as barely seaworthy as it rides the deep waves, while the men are rendered as broken and in utter despair. One old man holds the corpse of his son at his knees; another tears his hair out in frustration and defeat. Several bodies litter the foreground, waiting to be swept away by the surrounding waves. The men in the middle have just viewed a rescue ship; one points it out to another, and an African crew member, Jean Charles, stands on an empty barrel and frantically waves his handkerchief to draw the ship’s attention.

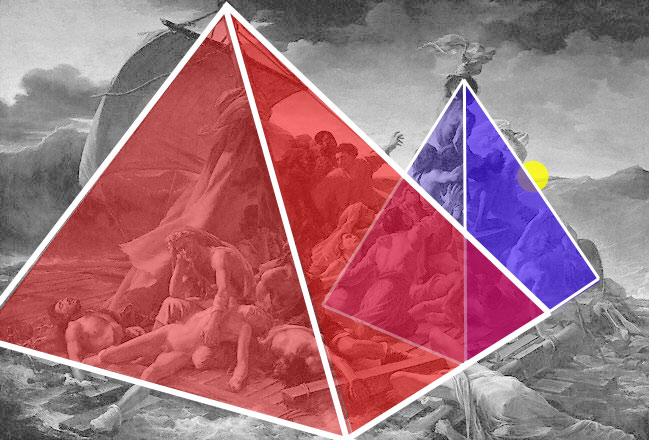

The pictorial composition of the painting is constructed upon two pyramidal structures. The perimeter of the large mast on the left of the canvas forms the first. The horizontal grouping of dead and dying figures in the foreground forms the base from which the survivors emerge, surging upward towards the emotional peak, where the central figure waves desperately at a rescue ship. The viewer’s attention is first drawn to the center of the canvas, then follows the directional flow of the survivors’ bodies, viewed from behind and straining to the right. According to the art historian Justin Wintle, “a single horizontal diagonal rhythm [leads] us from the dead at the bottom left, to the living at the apex.” Two other diagonal lines are used to heighten the dramatic tension. One follows the mast and its rigging and leads the viewer’s eye towards an approaching wave that threatens to engulf the raft, while the second, composed of reaching figures, leads to the distant silhouette of the Argus, the ship that eventually rescued the survivors.

Overall, the painting is dark and relies largely on the use of somber, mostly-brown pigments, a palette that Géricault believed was effective in suggesting tragedy and pain. The work’s lighting has been described as Caravaggesque, after the Italian artist closely associated with tenebrism, a dramatic, pronounced chiaroscuro, creating a violent contrast between light and dark. Even Géricault’s treatment of the sea is muted, being rendered in dark greens rather than the deep blues that could have afforded a contrast with the tones of the raft and its figures. From the distant area of the rescue ship, a bright light shines, providing illumination to an otherwise dull brown scene, but bringing only an almost futile hope for the few survivors.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!