Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

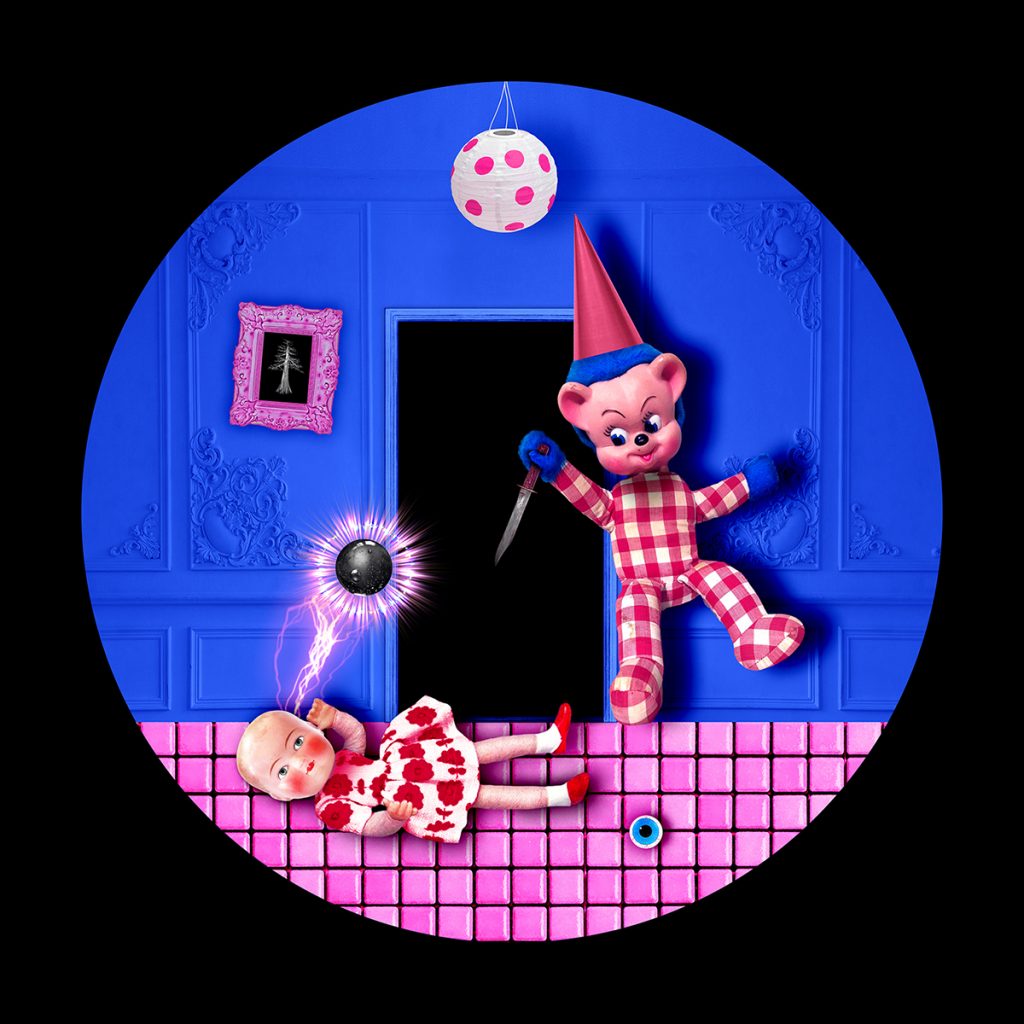

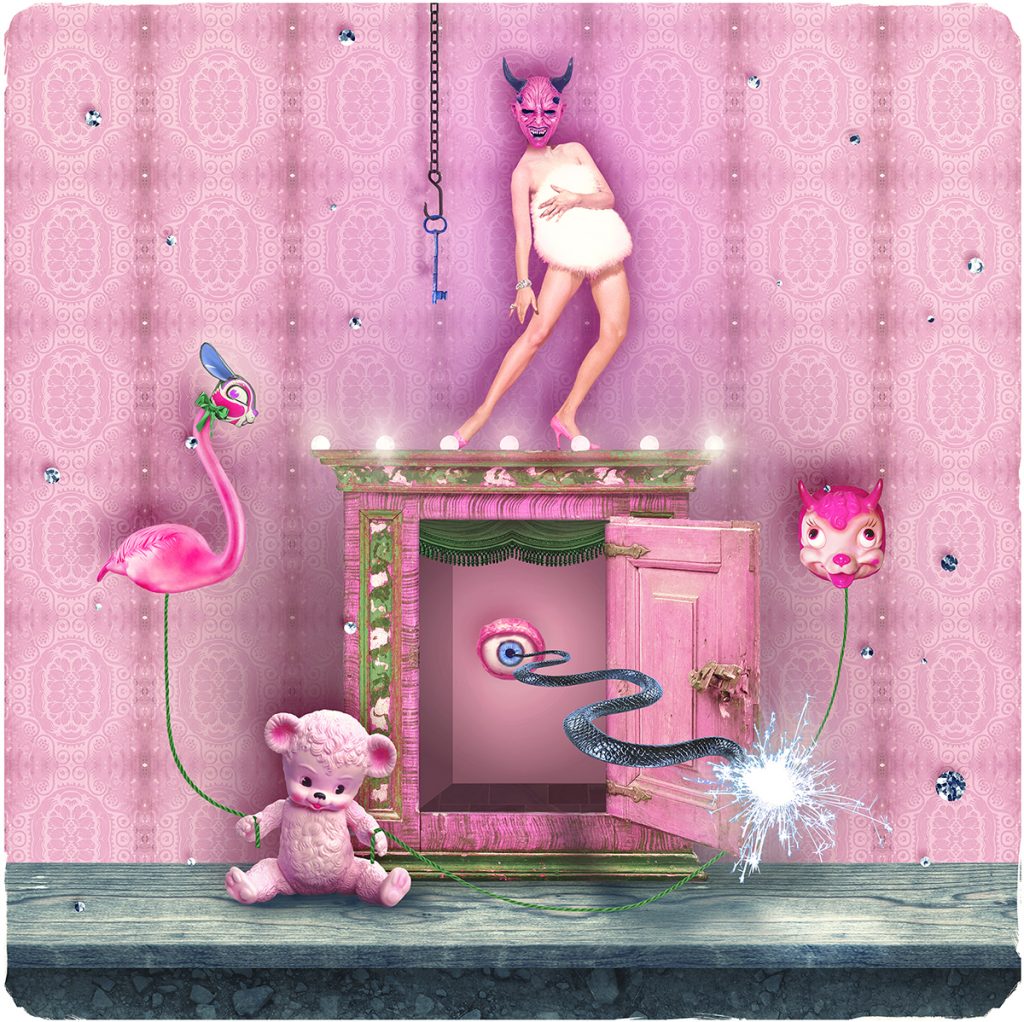

Viewing the art of Mia Makila is like walking into a labyrinthine psyche masquerading as a shop. You open the door, the bell rings, and you realise that you’re the only customer. This shop only accepts one customer at a time because with each one it shifts its configuration and shows you something new. The shelves are stacked, tall and very deep. The aisles recede far into the distance and darkness where things whisper amongst themselves and watch from the shadows.

In the foreground, everything is light, inviting, and often disarmingly pink. The shop is filled with oddities, from children’s toys to furniture, but what strikes you the most are the characters. They are strong, unapologetic, and many of them look like demons. They don’t care that they’re unlikeable, and have come forward from the maze-like shop floor to present themselves in all their glory. They stand with alarming proximity to the viewer: we question what we’re seeing, and even though we might not want to, we are compelled to admit that we understand it.

We’ve stepped into a complicated world where we are invited to face those characters, on our own terms, and alone. It is confrontational, surreal, even bizarre. Mia’s shop is even more extraordinary than that: all the time that we’re staring as these faces – the lustful, the malicious, and the nefarious – we are naming them. This is what you do with demons though isn’t it? You name them to have power over them.

Enjoy!

I feel that your art reflects painful experiences, whether these are events in your personal life, or your reactions to events in the world. How does the vibrant colour palette, childhood imagery and the overtone of fun fit in with your expression of these experiences?

I use my art as a way of making sense of things – both when it comes to myself and the world. I am a highly sensitive person and absorb many levels of reality at the same time, like it’s a cake and I can see all the layers underneath the frosting. I am especially receptive to the subtle “in between” layers of reality – like: sudden changes in human energies; the mood and atmosphere of a place or situation. I also have a big curiosity when it comes to exploring details of reality and life, this looks bizarre when you look closer. I believe this is how children absorb the world as well. I guess I was able to hold on to this way of absorbing things – so the natural language of expressing it is through the palette and visual mannerisms of a child. It feels like home to me.

When you zoom out, from outer space, and look at our world and all the everyday details, it looks even more bizarre and strange. I always like to play around with perspectives like that. All the stuff we take for granted becomes truly surreal and funny if you put it in a different context. For example, an excavator kind of looks like a big insect; the sound of a worn-out wheel of a shopping cart sounds like a tragic cry for help, if you didn’t already know what it was. So, everything has a dimension of comedy to it, just like comedy always has something serious or dark at its core.

It is also easier to examine and face difficult topics and painful truths when you add some contrast to it, like bright colours, juxtapositions or unexpected details. Take the expression of rage as an example: the big bulging eyeballs, the tight lips which look like a sphincter, trying to hold back something awful; the red face, the stiff body vibrating from anger – it’s so grotesque and weird. Instead of being intimidated or scared of something, I try to look at it with a sense of humour and it immediately starts to look quite ridiculous!

What does your art say about your understanding of PTSD and recovery?

During the years I endured an abusive marriage, I wasn’t allowed to make art that was based on my experiences of this abuse. He would punish me for making darker works, so I would paint more flattering motifs instead – still life, angels and flowers. Whenever I would paint something dark, I made sure to throw it away so he wouldn’t discover it. When I found the strength to leave him and got back on my feet, I started to express the darkness I had kept inside, through my art. I took a pair of scissors and started to destroy the books I had kept from our separation. I used the paper cut-outs from old photo books and art books to create surreal mixed media collages. It was so liberating! All the anger, the fear and the shame connected to the abuse came out through the collages. If you look at those early collages from 2006, you can see how explosive this chaos was. I don’t know what would’ve happened, if I hadn’t let it out through my work. My art has saved my life many times.

At first, I didn’t even realize that I had been through a trauma or that I was suffering from complex PTSD. It wasn’t until I started the process of trauma treatment in therapy that I could see how devastating it really was. That’s when the chaotic scenes in the collages stopped and I started to paint demon portraits, with just one figure at a time, with one single core expression. The portraits are representatives of all the horror elements I had been through. People say “face your demons” and that’s what I did. Literally. It was part of understanding my trauma and facing the pain of it. If you look at my art in a straight timeline, you can see the process of trauma recovery. All the different phases of PTSD recovery are there. From the entangled internal chaos to explorations of complex emotions and finally the process of healing.

Now, my art has shifted focus from the demon portraits back to surreal worlds – but this time without the suffocating chaos – perhaps because I am integrating myself in the real world again, after many years of isolation. I have also changed my approach to the trauma itself from focusing on my own experience of it, to exploring the twisted motivations and behaviour of the perpetrator. It liberates me from any shame or guilt I have felt, and that connected me to the traumas – it never belonged to me in the first place. Meditation has been a great tool in my recovery process. To connect to one’s core is essential for overcoming trauma – it has helped me become a better artist as well. My art has become even more honest and more to the point.

Your paintings are full of symbolism that is open for anyone to process: has anyone ever taken something totally unexpected away from viewing your art? How do you feel about the interpretations of strangers when you send something so personal into the public arena?

Once I have finished a piece, my work with it is done. I have nothing to do with people’s interpretations of my work. It’s out of my control and it’s not my place to tell them what to see, how they should feel about it or what emotion it should evoke. However, I don’t like to be misunderstood. I use a lot of upside-down crosses in my art, so of course people assume that I worship Satan – and I don’t. I don’t believe in any God or in any Antichrist. My abuser was very religious and sometimes he attacked me because he was convinced that I was possessed by the Devil. By using the upside-down crosses, I get to mock his delusion and reclaim my true identity.

I have always felt observed and judged by people close to me, so that’s why I use a lot of all-seeing eyes in my art. I had a serious case of eczema as a child, I was always bleeding and breaking out in rashes all over my body. This is why I use polka dots and rotten, melting or bleeding skin and flesh. I never use macabre or grotesque details in my art just to provoke people or to gross them out. I wouldn’t want people to think I make dark art for shock value.

My audience and fans make their own interpretations of my personal mythology and at times I see how cultural differences can make it look a little distorted. In Sweden, where I live, they see my art as pure horror, because we don’t like to talk about difficult and complex emotions here. Swedes tend to believe that intellectual depth translates to ‘darkness’. I think this is why Ingmar Bergman’s films were more appreciated internationally, than they were here in Sweden. In Russia, they claim I am suffering from schizophrenia and that I am mentally deranged, probably because their culture is so controlled and every challenge to their perspective is censored and repressed.

As suggested by my last question, I for one view anything I create as part of myself. Do you feel the same, and does it make you want to draw your work inwards rather than to share it? Does sharing it make you feel vulnerable?

I make art and I write because it is a natural part of me, like another way of breathing. I could not live or survive without it. It is an extension of who I am. In the creative process, it’s all about getting the expression right, or finding the precise details to show the bigger picture of something. It’s all about getting something out of me. It’s not really about showing it to the world, but rather getting rid of an internal obsession or compulsion and to externalize my anxiety, perhaps similar to self-harming behaviours. I guess I do feel vulnerable during the creative process but once I’ve gotten the expression out, it doesn’t belong to me anymore. It is satisfying to me. Sharing my art with the world never makes me feel vulnerable – it makes me feel strong and powerful.

Many of your works are deeply visceral, like a brightly-lit horror movie. I like to think that their brightness is part of a process where you are throwing light onto subjects that are usually taboo, or shrouded in shame. Is it fair to say that you want to break down some barriers when it comes to talking about traumatic experiences? Could the same apply to exploring darker human desires as well?

That’s a great observation! You know, I feel like a warrior at times and I am really passionate about breaking down barriers regarding difficult subjects – like domestic violence and psychological abuse. I have recently started a Swedish podcast called Epilogen Podcast dedicated to this, and I am currently writing my first novel which deals with more complex aspects of psychological and sexual abuse. Through my art I’m also trying to expose the warped perspective on female sexuality and the female body. How it’s objectified and over-sexualized in both obvious and subtle ways. I can’t stand any form of censorship but somehow I have often found myself trapped in relationships or situations where I’ve been censored and erased as an individual, both intellectually and sexually. My voice, my boundaries, my desires or my needs, haven’t been allowed to exist. Many times my whole existence has been gaslit and I have been forced to adapt to someone else’s needs and wants, and in the end I’ve been completely ‘owned’ by that person. To me that’s way more horrific than any obvious horror element that you can put into art.

I do deal with desires in my work as well, but perhaps I define the concept of ‘desire’ differently than most people. My desire has always been, and still is, to be able to be myself without being punished for it: to exist on my own terms. I use a lot of flames and fire in my work to symbolize this desire, or as a symbol for the external resistance to it.

As long as you don’t hurt other people, you should be allowed to be exactly who you are and embrace all the flaws and weird quirks. Those are things that create so much unnecessary shame in people. Shame creates distance and distance creates barriers and now we’ve come full circle!

Leading on from there, do you feel that the raw sexuality of women is often either misinterpreted, or overlooked altogether?

Women are only allowed to be virgins or whores in this patriarchal world. If she’s a virgin she must be conquered and turned into a whore – and if she’s a whore she must be punished and humiliated. It means that women always must be punished for being sexual beings. When women become mothers, they must be de-sexualized and then go through the process again. They become either ‘unfuckable’ saints (re-virginized) or milfs (another type of whore). And as a woman, we have been manipulated into thinking that there’s nothing more degrading than being ‘unfuckable’, so we’d rather focus on how to maintain our ‘whore’ status. It’s all done in a very subtle way but it’s even more detectable now after the rise of the #metoo movement. Try re-watching all seasons of Sex and the City (and the awful movies that followed), without seeing this patriarchal pattern!

On the other hand, we are bombarded with obsessive content (articles, movies, documentaries, etc.) regarding ‘the mysteries of female sexuality’, like the female orgasm is some kind of mystical phenomenon, and her desires are part of a ‘feminist statement’. It’s all twisted and distorted because we are looking at female sexuality through a collective male gaze. It is hidden misogyny, and always from a porn-polluted perspective. As long as I live, I will work with these themes in order to raise awareness of how women are being punished for their sexuality. It’s grotesque.

Your work seems to portray a feminine interior landscape that is at odds with traditional expectations of what some would suggest that should look like (even in 2020!). What are your influences: for example do you find that women are in fact more than capable of violence but need to internalize it? Are we repressed in terms of outlets for the expression of emotions which are conventionally seen as more masculine? Would you describe your art as feminist?

I am not really interested in labelling myself as this or that but with that being said, I believe that if you don’t support feminism or feminist goals – whatever gender you belong to – you are a misogynist and not a good person. Feminism as a concept in our society is a sad thing, if we ask ourselves why we need this concept in the first place. It’s the same thing with racism. Both concepts are deep wounds in the body of humanity itself. Just the fact that Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) is like a collage of real concepts and events that can be found throughout history, instead of being all fictional horror fantasies, says a lot about the deep wound of misogyny. The fact that Atwood’s novel feels super relevant is really creepy. The ideas of feminism should simply be a natural and normal part of the texture of the human consciousness, and not a political ‘-ism’.

I guess these thoughts make me a true feminist after all, don’t they? Then I am also a “love-ist”, who believes in the concept of love, although that too should be a natural part of humanity, do you get my point?

I am against all forms of destructive violence but I believe that if we could channel the oppressed and repressed collective female rage correctly, it could turn into a positive force to make actual change. My art has a lot of anger and aggressive energy in it, as a mini version of this philosophy. I want to contribute to this change in all ways possible.

There are a lot of women who I look up to, especially women who are fearless about speaking up against patriarchal systems and structures, not necessarily in obvious or conventional ways.

People tend to refer to me as Pippi Longstocking, perhaps because she’s also a Swedish girl with red hair who has a lot of imagination and is not afraid to demand to exist on her own terms. Astrid Lindgren, who wrote the books about Pippi, is a source of inspiration for me. She did not accept the expectations men had of her, and I like that. I find a lot of motivational inspiration in Michelle Obama, Brené Brown and Marina Abramović. I am attracted to truth-tellers with an empathetic world view.

Back to colour, pink is very prominent in the architectural/material elements of your paintings (floors, furniture, toys), and seems incongruous with the often grotesque imagery. I also see that you often use a similar pink for skin. What does it represent to you?

Maybe it’s just me but I see pink as the colour of our insides, of our inner worlds. Meat is pink. Most organs are pink. And on the inside, we all look the same (with a few exceptions of course), and on the inside, we are equals. It is beautiful to me. I use pink as an indication that what you see is a metaphor for something else – something that is only present inside ourselves. I often use pink also as a symbol of femininity and female gender issues. This is why I often use hot pink against baby blue – to show the juxtaposition between the aggressive feminine energy against the intellectual immaturity of the patriarchy.

I feel that your work is incredibly complex, so how do you feel about the labels ‘lowbrow’ and ‘horror art’? This is not to suggest that these genres can’t also be complex, but I’m not sure that your work can be labelled so easily.

I don’t feel at home in any label, or in any geographic place either for that matter. I struggle with the question “where do I belong?” all the time. It is a sensitive thing for me and I have always felt like a misfit here in Sweden. We don’t even have an alternative art scene for obscure art styles. This motivated me to found the online artist collective Art Monsters of Sweden in 2018, for Swedish artists within darker art genres. I am much more acknowledged internationally and thanks to social media, I have an audience all over the world. This makes me feel like I might have found my place in the world after all.

I don’t mind when people describe my art as ‘lowbrow’, however the label has more or less been replaced nowadays with the term ‘pop-surrealism’. Because I absorb external things very intensely, my inspiration comes from many different sources, like folk art, lowbrow, outsider art; film directors like David Lynch, Alfred Hitchcock and Tim Burton; photographers like Cindy Sherman, Roger Ballen and Pierre & Gilles; early renaissance masters; pop culture; and early Disney classics. I guess my art is like this delicious “style soup” and people seem to enjoy it! I usually describe my art as ‘kitschy, gothic pop-surrealism’.

Who/what do you consider to have influenced you during your early development as an artist?

When I was 15 years old, I discovered Frida Kahlo and fell in love with her visual world. I felt so connected to the way she used her pain to create a personal mythology in her work. It opened the door to expressing what I had been keeping inside.

After I graduated from high school, I studied art history and history of ideas. I focused on early renaissance art and the carnival-esque art of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. This influenced my art as well and these artists taught me that there are no limits when it comes to surrealism: you can mix any contradictory details and break every rule of logic. Bosch and Bruegel were great inspirational sources for me when I tried to describe my personal version of Hell (i.e. the abuse).

You don’t shy away from the baser human instincts and characteristics. Lust, physical pain, bodily fluids, orgasms, sexual impropriety, violence and rape can all potentially be read into your work. Your art feels very natural in this respect, but at the same time it is still filled with tension, and can be truly shocking. Is this an ambiguity that you create deliberately? Is honesty in your work of paramount importance?

Honesty is the loudest colour in my palette. To be a truth-teller is the biggest motivation for me, when it comes to any form of creative expression. As I explained earlier, I find life rather grotesque and surreal. I use the bodily fluids in my work as a reminder of this. We might feel either ‘normal’ or ‘freakish’, wrong or right, ugly or beautiful – all while our bodies are producing smelly waste which comes out of us in various surreal ways. It’s like we pretend it’s not there, while we are busy feeling all these emotions and comparing ourselves to each other. There is this funny little figure in the left lower corner of Dulle Griet by Pieter Brueghel from 1563, who is basically just a butt with a face and leg-arms, who is feeding himself through his mouth/butthole with a spoon. That is hilarious and a great description of the human body.

We also like to pretend that we don’t know that gelatine is made from animal carcasses including skin, bones, and connective tissue. So, candy is basically made out of true horror. Stuff like that truly inspires me.

I look at primitive emotions and basic human instincts in a similar way. I see them as animalistic energies and some can be super dark and intense, others are like magic (in the same way that the Big Bang is magic). That’s when we are really connected with nature, and beyond. It’s both frightening and powerful. Perhaps this is why I use animals in my art and elements like tails, horns, saliva, claws and fangs, but also planets, stars and dark space.

What I am most scared of in life has already happened to me. I create the scenes of violence and sexual abuse to exorcise them out of me. They are very personal, almost private. I use the ‘Lolita’ character as an avatar of myself, but she’s not a child (except for The Lolita Express piece about the Epstein case). She’s just not allowed to have the freedom and independence of an adult. I could never use myself in my work because I’m so honest and open already: it would be like giving away everything I am.

An artist’s work during their lifetime often charts a journey. Do you feel that this can only ever be retrospective, or do you sometimes make art that takes you closer to where you’d like to be in the future? Do you see multiple versions of yourself’ – past, present, future – in the work that you create?

During this period of self-quarantine, I have done some intense soul-searching and it has resulted in a few life changing decisions and a new direction for my career as well. I feel like I am expanding my creative force far beyond visual art. I am dedicating more and more time to writing and podcasting. I would love to do lectures, write books, and perhaps even direct a movie one day.

I usually describe myself as a mix of Pippi Longstocking and Ingmar Bergman. I have an equal desire to be playful, to create colourful worlds, but at the same time to dive into the depth of my intellect and to wallow in melancholy and angst. So, perhaps the Russians are on to something after all: I do have this schizophrenic element to my artistic persona – ha! I think I just need a bigger playground for my inner Universe.

Finally, you have mentioned that you are writing your first novel which will deal with more complex aspects of psychological and sexual abuse. I understand that it will come firstly from experience, but will you ultimately write it to be multi-dimensional and fantastical?

The novel is partly based on my own experiences of a relationship with

‘ambient abuse’ (super subtle and stealth-like) and without giving too much away, it includes a section based on a famous whimsical story. In this chapter, I wish to illustrate the warped sense of reality that the victim feels after having suffered mind-games, gaslighting and manipulation for years. In this relationship, I didn’t notice the abuse until four years later when he raped me in my sleep and I didn’t even bother to try and stop him. I had completely separated myself from my own experiences. That was the turning point. I think I’m writing this story to answer my own question: “How was this possible?”

If you’re looking for beautiful masterpieces to beautify your wall – here is the DailyArt 2021 calendar for you!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!