Masterpiece Story: The Setting of the Sun by François Boucher

With sweet putti, handsome gods, beautiful nymphs, vibrant colors, and elaborate compositions, The Setting of the Sun is a testimony to François...

James W Singer 8 February 2026

Claude Monet loved gardening almost as much as he loved painting. When he finally settled in Giverny, he created a natural masterpiece which acted as inspiration for much of his later art. His garden was a retreat, a consolation, an ongoing experiment, and a source of endless pleasure. The water lily pond and the Japanese bridge have become synonymous with Monet’s art, but here we take the path into the very heart of his garden.

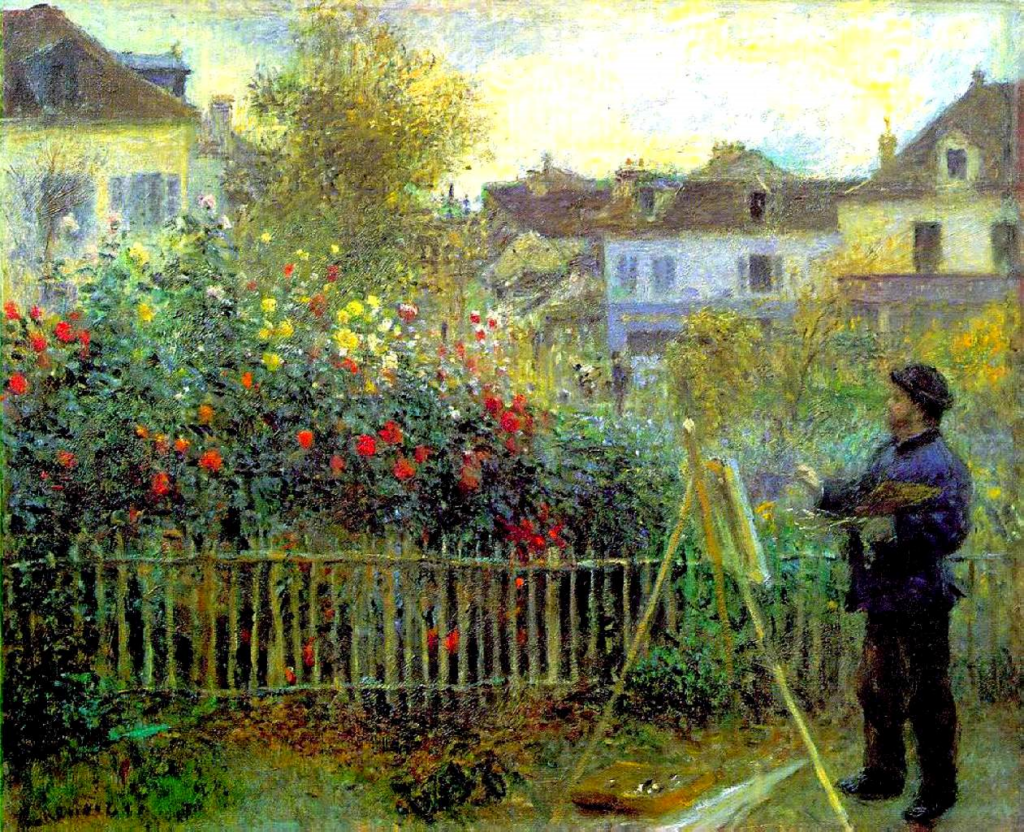

August Renoir, Claude Monet Painting in His Garden at Argenteuil, 1873, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, USA.

Claude Monet (1840–1926) was a painter who sought out nature. Even when he turned to urban subjects, like his series of views of the Thames in London, he did so to explore how they looked in different weather conditions and different times of year. From his early days, working on the Normandy coast, through his exploration of light and water at Argenteuil on the outskirts of Paris, to his trips to Norway and Antibes in the south of France, he consistently painted plants, trees, and natural forms.

Nature provided a readymade palette of strong colors; it provided constant change and movement. Nature also gave Monet’s art roots: he could look at, and build on, the work of the previous generation of landscapists, like Théodore Rousseau and Eugène Boudin, who had also been drawn to the shifting versatility of the natural world. Like them, Monet wanted not just to paint nature, but to be in nature. He worked outdoors in all weathers, experiencing as well as observing the natural world and seeking to capture that in his canvases.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil, 1881, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Throughout his life, Monet was also a keen gardener, growing plants and tending plots even when he was only renting properties at Argenteuil (1871–1888) and Vétheuil (1878–1881). Gardening allowed him to manipulate nature in the same way as he manipulated it on canvas—he could choose colors and create compositions. It also gave him an element of convenience. How much easier it would be to simply look out of his window, or walk out of the studio door, rather than traipsing across fields with his equipment or sitting unsteadily in his studio boat.

As a renter-gardener, Monet grew annuals, flowers he could plant from seed in a single season. He also used large pots as planters, which he could take with him. The towering sunflowers at Vétheuil, for instance, gave him a quick fix of height and color. The blue-and-white pots gave a sense of repeated order and structure. Similar pots can be seen in his earlier painting of the house at Argenteuil.

Claude Monet, Women in the Garden, 1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Monet’s early works use gardens simply as a convenient backdrop for figures. Women in the Garden was painted outdoors in the grounds of the house he was renting in the Paris suburbs, with his future wife posing for the figures. However, Monet’s interest here is not in nature but in the extravagant dress of the women, particularly in how white fabric could be represented under different light conditions.

Increasingly, however, the balance shifted; figures became incidental, and the focus was on the plants and flowers themselves. In Monet’s Garden at Vétheuil, the three figures on the path are literally dwarfed by the plants, barely noticed at first as they merge into the dappled light. By the time he paints The Path at Giverny, figures are just implied. The viewer is asked to effectively complete the picture by walking along the garden path. One might imagine Monet waiting at the door to greet us.

Claude Monet in front of his house at Giverny, 1921, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

When Monet arrived in Giverny in 1883, he had no idea that it was where he would spend the rest of his life. Le Pressoir was the latest in a series of rented properties, conveniently located near the river Epte and with two acres for him to garden in. As his financial situation became increasingly secure, he bought the property in 1890 and then added to the existing land, which he landscaped into the water lily pond. In 1892, he built greenhouses and developed a collection of orchids. With enough money to employ gardeners and indulge his passion, he became interested in breeding new plant species.

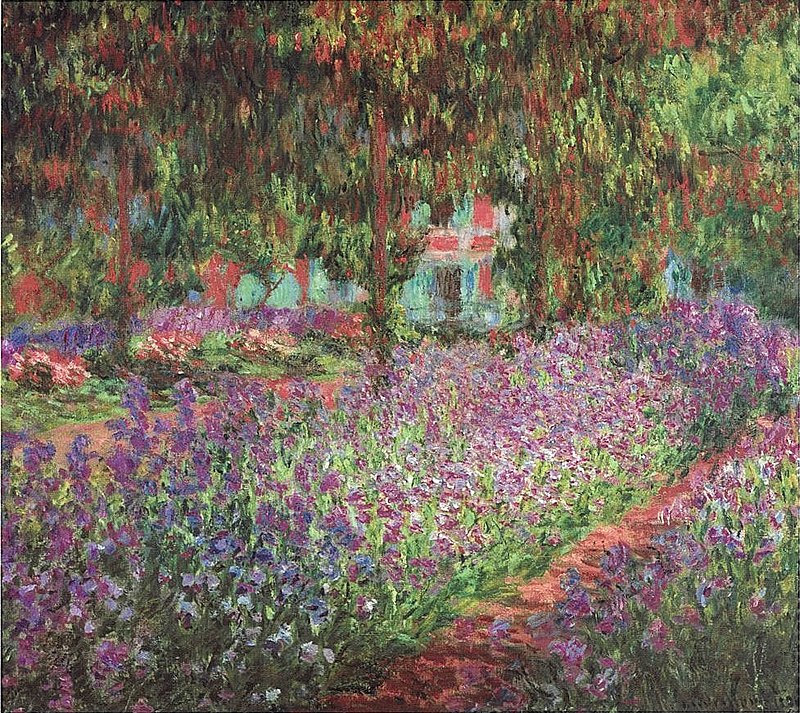

Before all that, however, he had adapted the garden from the existing formal vegetable plot with box hedges and cypress trees into a freer design scheme featuring his favorite flowers. He loved roses, dahlias, chrysanthemums, and poppies: showy, colorful flowers. The beds were mounded into a “carp’s back” hump to show off the flowers, which he grouped into large color blocks, like the sea of irises below. There were 17 different varieties of iris at Giverny, a good indication of how interested a plantsman Monet was.

Claude Monet, The Artist’s Garden at Giverny, 1900, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France.

Monet’s art, and Impressionism in general, is associated with looseness and movement, but his paintings often have an underlying sense of structure, based on an important, sometimes frequently repeated, motif. During his early years at Giverny, when he was painting the surrounding area more than the garden, he was drawn to the strong verticals of poplar trees and the geometry of haystacks.

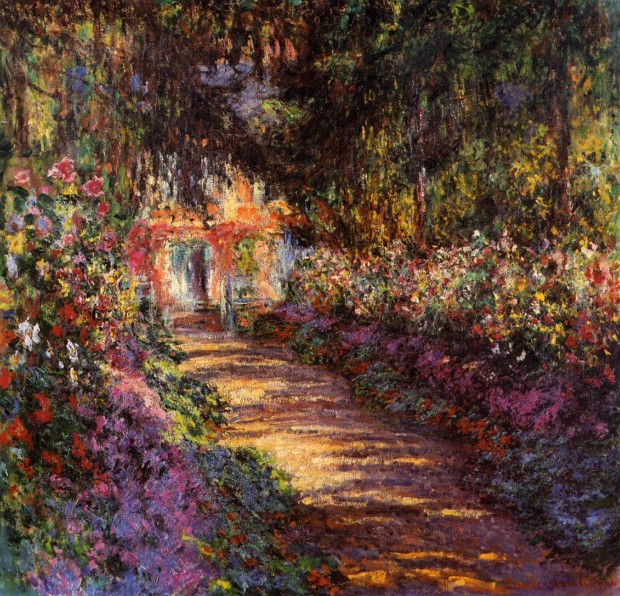

Claude Monet, The Path in Monet’s Garden at Giverny, 1902, Belvedere Museum, Vienna, Austria.

At Giverny, he would, of course, famously build a Japanese bridge to provide that structural focus in his water lily pond. In the main garden, he retained the bones of the formal design he had inherited. The straight path that led up to the house was lined with cypress trees, which were pruned to become the supports for his roses. The trunks were eventually replaced by metal arches after they rotted.

A rectilinear grid of gravel paths divided the flower beds. Vertical support frames and standard roses created height. Hard brick edges and planted borders of pinks and nasturtiums gave a sense of containment. The organized structure is very obvious in contemporary photographs.

If Monet the gardener liked structure, Monet the artist increasingly rejected it in his work. In the Path at Giverny, the gravel is visible, a central line of recession which leads the viewer into the painting and toward the house in the background. The vertical trunks are also shadowy presences. However, nature is taking over: the nasturtiums are trailing across the path, the plants are obscuring the house and even the sky. Monet uses pom-pom-like spots of sunlight and areas of deep shadow painted with the same colors he uses in the flower beds to dissolve the structural solidity of the path even further.

Claude Monet, The Path in the Garden, 1901–1902. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

He adds to this sense of natural chaos by employing loose, dashed, tactile brushwork, which creates a storm of confetti on the surface of the painting. The viewer is at once made more aware of the fact that this is a two-dimensional canvas, and less able to work out the details of the scene. This sense of partial abstraction was set to increase during the last part of Monet’s career.

Although Monet often painted snow, fog, and frost, he did not paint his garden at Giverny in the winter. He painted the path on more than one occasion, but it is a place of perpetual sunshine and color. He idealizes the garden into a self-created paradise. In the Path at Giverny, we are offered a chance to enter the garden, but generally Monet’s paintings give little sense that there is a world outside the gate. Even the sky is only occasionally glimpsed.

His Giverny paintings might be seen as part of the tradition of enclosed gardens, hortus conclusus, which in Medieval art traditionally represented Christian purity and the Garden of Eden. Monet was not specifically exploring religion in his garden paintings, but he was creating places of security and ideal beauty. He described an 1873 painting of his garden as “decorative,” and his swathes of brightly colored flowers have a tapestry-like quality. This is paradise created jointly by God and the artist.

Claude Monet, The House Seen from the Rose Garden, 1922–1924, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, France.

As Monet grew older and his eyesight started to fail, his world became smaller and his garden became more important. He began to explore specific parts of the garden with almost obsessive repetition, most famously, of course, his water lilies. A series of pictures of the house from the rose garden not only swamps the building beneath a swirl of color but also abstracts the plants into an agitated haze of brushstrokes. The reality of the garden no longer seems the point; this is about creating a sensation of what it means to Monet himself.

Monet’s art is often characterized as observation, the recording of a moment in time. The Path at Giverny, along with his other garden paintings, reminds us that he was much more considered than this. He planned, he structured, he composed, as a gardener as well as an artist. More importantly, however, he felt deeply. Monet invites us to follow The Path at Giverny into the special place he had created. He invites us to experience his own, complete, and perfect world.

P.S. If you want to learn more about Monet other fellow Impressionists, enroll in our online course on French Impressionism!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!