Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

Edward Hopper created his peaceful seascape masterpiece Ground Swell with hinted implications of social disengagement, emotional loneliness, and foreboding danger. Let’s delve into it!

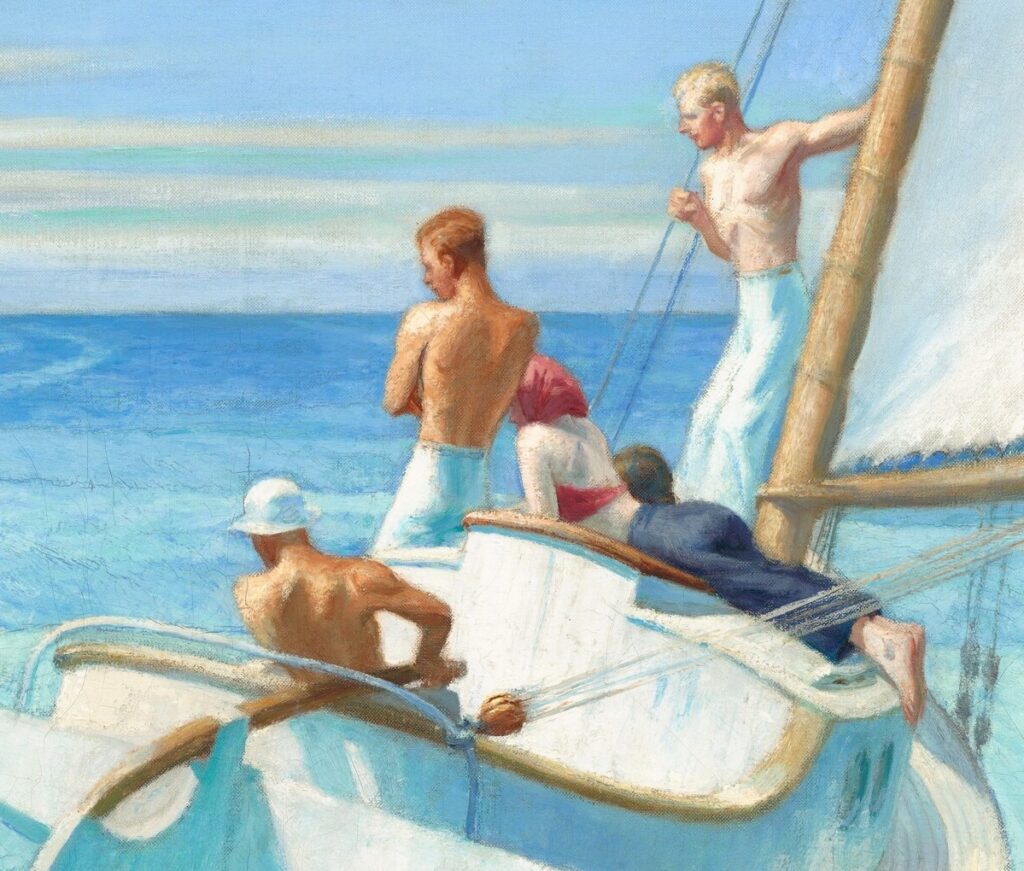

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

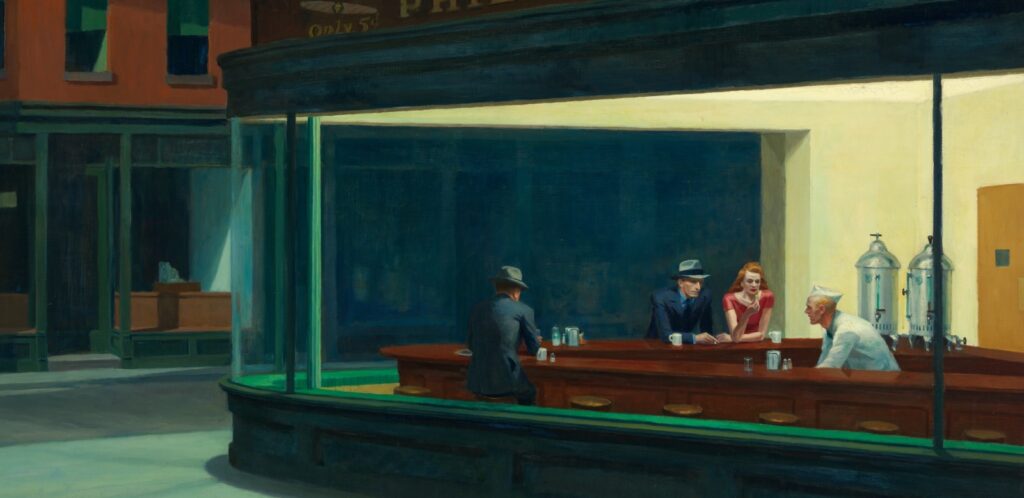

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) was an American painter known for his images reflecting isolation and loneliness like his most famous painting, Nighthawks. He was born in Nyack, New York, a port on the Hudson River with an active shipyard. It is said the riverside activities created Hopper’s lifelong appreciation for waterside living.

In 1934, Hopper and his wife, Josephine, moved to Truro, Massachusetts, which faces onto the expansive Cape Cod. They bought a house with a studio so that they could enjoy an idyllic coastal retreat while maintaining a reclusive existence. Hopper created many nautical artworks in their Cape Cod hideaway, including his seascape masterpiece Ground Swell.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Ground Swell is an oil on canvas measuring 91.92 cm high by 127.16 cm wide (36 3/16 in high by 50 1/16 in wide). It has an almost 4:3 proportion, similar to modern mobile phone photographs. The painting is a seascape with a bright palette and a serene subject. A white catboat floats in an aquamarine ocean against an azure sky. The captain and three passengers sit, stand, and lay aboard the sailing vessel. A dark metal bell buoy floats and bobs in the water nearby.

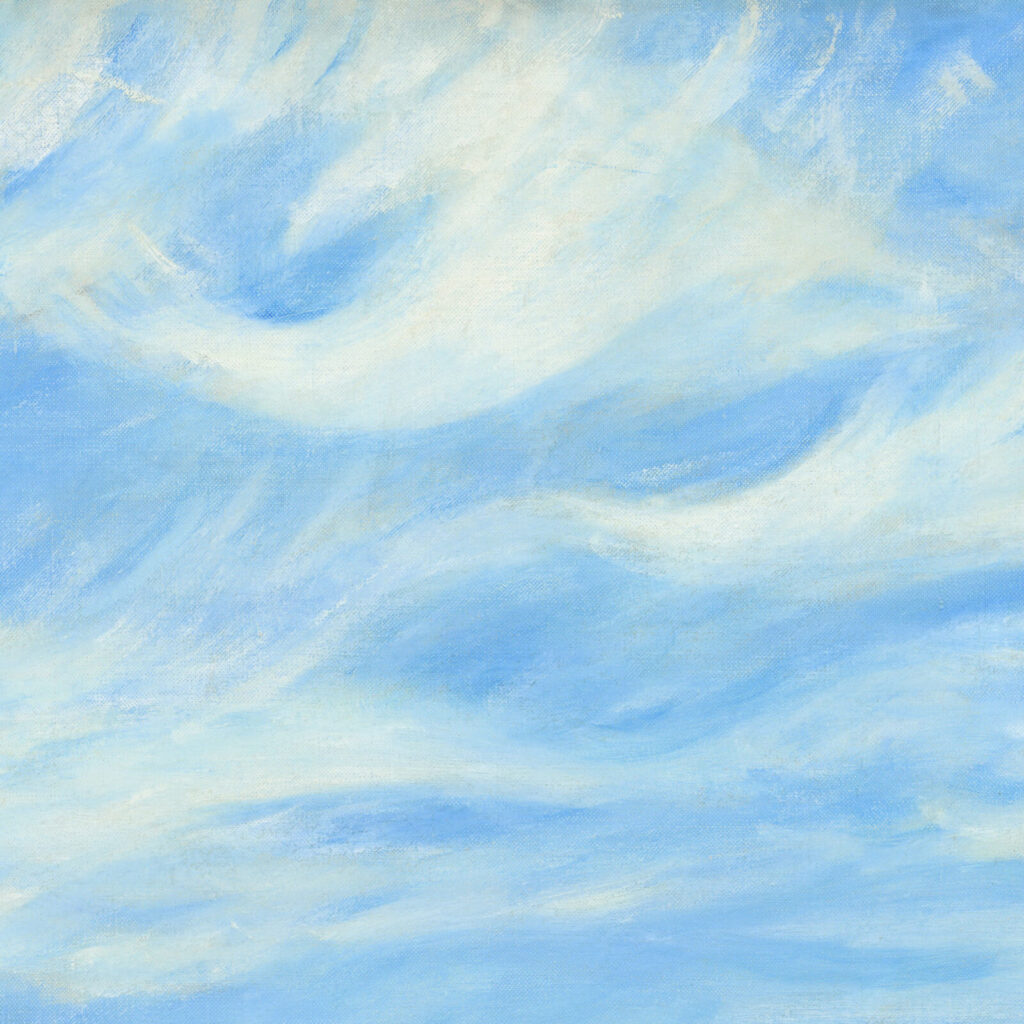

The boat and buoy rock against the approaching rolling waves while wispy cirrus clouds float above in the pale sky. Sunlight bathes the scene in clear hues. Everything seems at peace, but like undersea currents, there are hidden underlying elements. Upon deeper examination, there are implications of social disengagement, emotional loneliness, and foreboding danger.

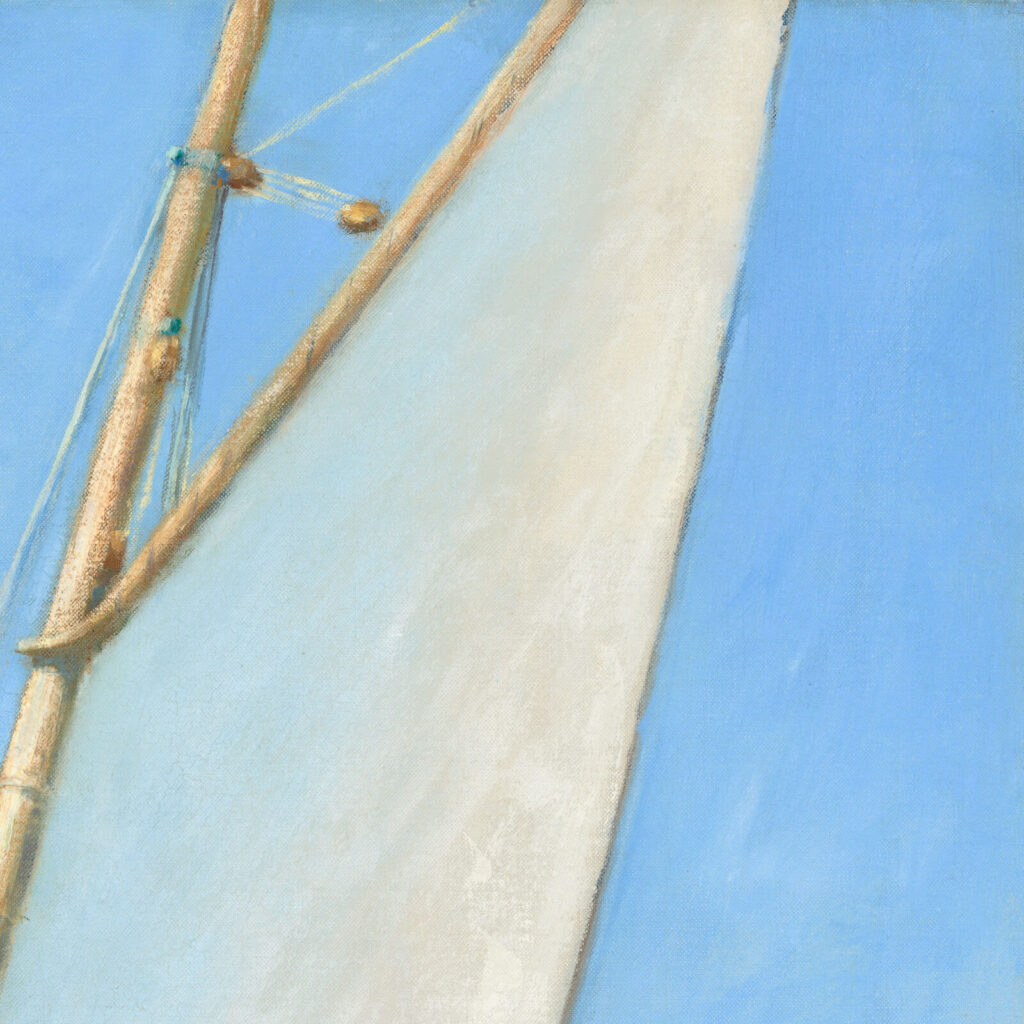

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The small white vessel is a catboat, a sailboat with a single mast set near the bow of a shallow hull. They are very popular in the Northeastern region of the United States, especially in the coastal states of New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. Hopper painted the catboat as heeling/leaning to its starboard as it crests a wave. The boat’s lean implies the rolling waves beneath it and the gentle movement of the seascape.

Interestingly, the boat’s movement does not disturb its rigging, that remains straight and tight. Hopper accomplished the rigging by drawing directly onto the painting with a graphite pencil, which was and still is considered an unusual final touch to oil paintings.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The captain and three passengers occupy the catboat: three shirtless men and one halter-topped woman. The woman is the most interesting because she is painted significantly differently from the three men. She is the only person to recline on the boat. She lays full-bodied on her stomach across the boat’s upper deck.

The woman is also the only person to wear red clothing. Her cherry head scarf and halter top are two bursts of red against the prevailing blue and white color scheme. They are like red flowers upon a piece of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain: delicate, small, and attractive.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The four figures share the same space. They are all confined to the boat. No one is swimming and exploring the ocean around them. The only exploration is with their eyes. They all focus on the bell buoy to their left. Through their collective gaze towards the bell buoy, they all ignore and disengage with each other.

They may be physically near each other, but their emotion and attention are disconnected. They are all lost in their thoughts and observations. For this brief moment, each member of the boating party is spiritually lonely in a crowd.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Loneliness and disconnection were national feelings during the 1930s when the United States was in the throes of the Great Depression. Many people felt a sense of loss and purposelessness, which can be expressed visually in muted, still, and empty spaces.

Hopper echoes this national mindset in his many paintings, most famously in Nighthawks and Ground Swell. The figures reflect the emptiness of modern American life. The American Dream seems unattainable or soured.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

The strong shadows found upon the right side of the buoy, boat, and figures indicate that the sun is to the left of the composition. Therefore, it cannot be noon as a noontime sun would cast very few shadows. The time must be either early morning or late afternoon. Due to the scene’s vibrant colors and the figures’ lethargic poses, it implies that the time is late in the afternoon. The viewer is witnessing a boating party in the later hours of its expedition. A full day of sailing now ends with a quiet moment of reflection upon a buoy.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

When Hopper painted Ground Swell, he followed the traditional technique of creating an underdrawing with graphite pencil on the canvas. Then, he later painted over the drawing with oil paint. Hopper’s pre-drawing created optical perspective and proportions for a sense of realism, as seen in the 19th-century masters Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and Henry Ossawa Tanner.

However, Hopper was not slavishly copying 19th-century realism. He fused Modernist abstraction to create a beautiful 1930s blend of visual clarity and geometric purity. Hopper reduced shapes and lines towards a simplified version of reality. This reduction is known as Abstract Realism.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The boat’s sail is a perfect example of reduced reality. It has a perfect gradient of diagonal shadow across its fabric, which is a miraculous achievement considering that Hopper used a palette knife to paint the sail. No blips or aberrations are marring the progressive shading. It is smooth and advanced, like smooth plastic. The viewer knows the sail is fabric, probably some form of linen or canvas, but its painterly depiction is softer and more resilient than mere fabric.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The resilience continues in the perfect ridge line of the rolling waves. They are ruler-straight without a breaking crest or foam. The four waves echo the distant horizon line and evoke a sense of patterned rhythm. They imply optical distance, with their ridges compacting closer together as they approach the horizon.

However, their omission of anomalies creates a very unrealistic conformity. The geometric regularity is serene and peaceful but improbable. The waves are the most significant element of Abstract Realism in Ground Swell.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

The lone dark element in the painting is to the left of the boat. The bell buoy is dark metal, which contrasts with the ship’s white body and the sea’s blue depths. It has a skirt of green seaweed or barnacles clinging to its watery base. The buoy deeply tilts to the right as the foreground waves disturb its upright position.

Bell buoys alert unseen or imminent dangers, such as large waves known as swells caused by storms or undersea earthquakes. Hence, the bell buoy alerts the passenger boat of the swell that it is currently surmounting. It has an ominous presence.

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Above the watery seascape is the azure blue sky marked by white feathery clouds. The delicate clouds depicted by Hopper are known in meteorology as cirrus clouds. Cirrus clouds owe their feathery appearance to their ice crystals, which form on the outer banks of storms. Therefore, for meteorology and weather-savvy individuals like Hopper, cirrus clouds indicate an approaching storm. This can sometimes be merely a thunderstorm but could also be an intense hurricane. Hence, cirrus clouds are beautiful signs of warning.

Ground Swell depicts the “calm before the storm” using the bell buoy and the cirrus clouds. Hopper completed this work on September 15, 1939. Could the storm be WWII which was declared in Europe at that time?

Edward Hopper, Ground Swell, 1939, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Detail.

Wendy Beckett and Patricia Wright. Sister Wendy’s 1000 Masterpieces. London, UK: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 1999.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Adam Greenhalgh. American Paintings, 1900-1945. Washington, DC, USA: National Gallery of Art, 2016.

“Ground Swell.” National Gallery of Art Online Collection. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

“Nighthawks.” Art Institute of Chicago Online Collection. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!