Celebrating M. F. Husain—One of India’s Most Iconic Artists

Maqbool Fida Husain’s artwork exudes a timeless quality that bridges the past and the present. His forms honor sacred traditions while also...

Guest Profile 2 October 2024

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) is primarily known and celebrated for his massive virtuoso portraits of late 19th and early 20th-century American, British, and French society figures. However, his work as a draughtsman has also received some attention in recent years despite his drawings being traditionally confined to museum storage. Sargent’s drawings demonstrate an incredible range of styles and subjects. Some help us to understand how he created his major works, while others stand out on their own as fascinating, finished artworks.

John Singer Sargent, Setting Out to Fish, 1878, pen and brown ink over graphite on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

As someone who considered himself an academic artist despite his decidedly modern flair, Sargent followed traditional academic drawing practices. He made countless drawings throughout his career. Starting young – as early as the age of four – he drew people, animals, landscapes, architecture, and other things he observed around him.1

The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns two sketchbooks in which fourteen-year-old Sargent depicted the Alps during a family trip there and other museums own even earlier drawings. He drew during his formal training in Florence and Paris and later made preparatory sketches for such famous paintings as Madame X, El Jaleo, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, and Gassed, not to mention extensive figure studies for his large-scale mural projects. Finally, in the last two decades of his life, Sargent drew more than 750 charcoal portraits of friends and patrons.2

Because he drew throughout his life for a variety of purposes, Sargent’s drawings demonstrate many distinct styles. Some are incredibly quick, loose, and casual, some are highly controlled and finished, while others fall somewhere in the middle. Many display the qualities we most admire in his oil paintings and watercolors, such as his loose, vigorous handling and intense chiaroscuro.

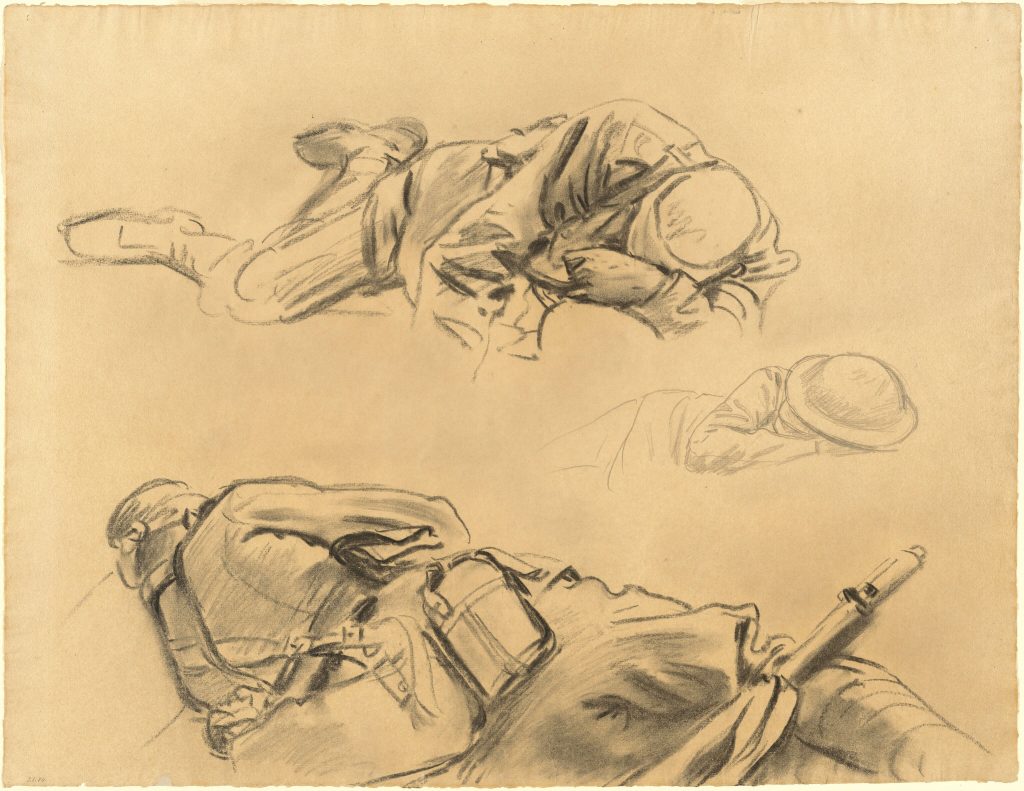

John Singer Sargent, Studies for “Gassed”, 1918-1919, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Although his major paintings may give the impression of spontaneity, they were actually the results of careful calculation. Sargent’s drawings demonstrate how he planned out his major works and reveal all the possibilities he considered. There are more than a dozen known studies for Madame X alone.3 Some focus on her face, others on potential poses and compositions.

This theme continued through other Sargent drawings such as his sketches capturing the movements and rhythms of Spanish dance for El Jaleo and studies of the two girls’ faces for Carnation Lily, Lily, Rose. Many of these drawings now live in museum collections (usually in storage), especially in the Boston area.

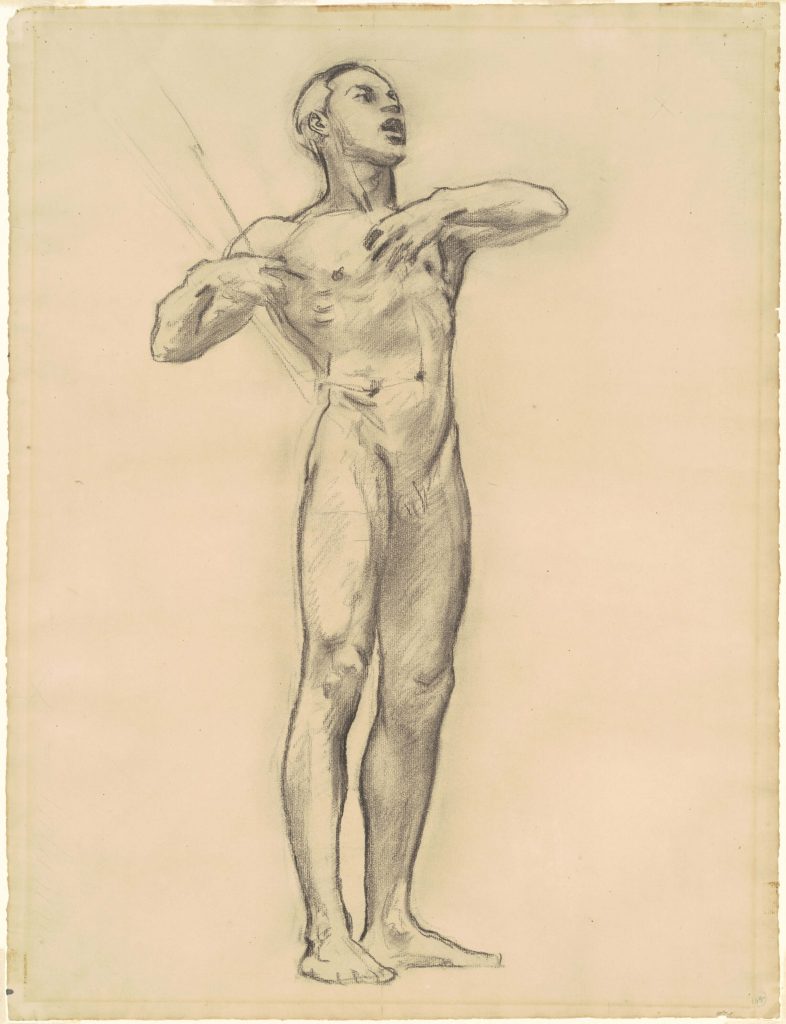

John Singer Sargent, Study of Orpheus for “Classic and Romantic Art” (depicting Thomas McKeller), c. 1921, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

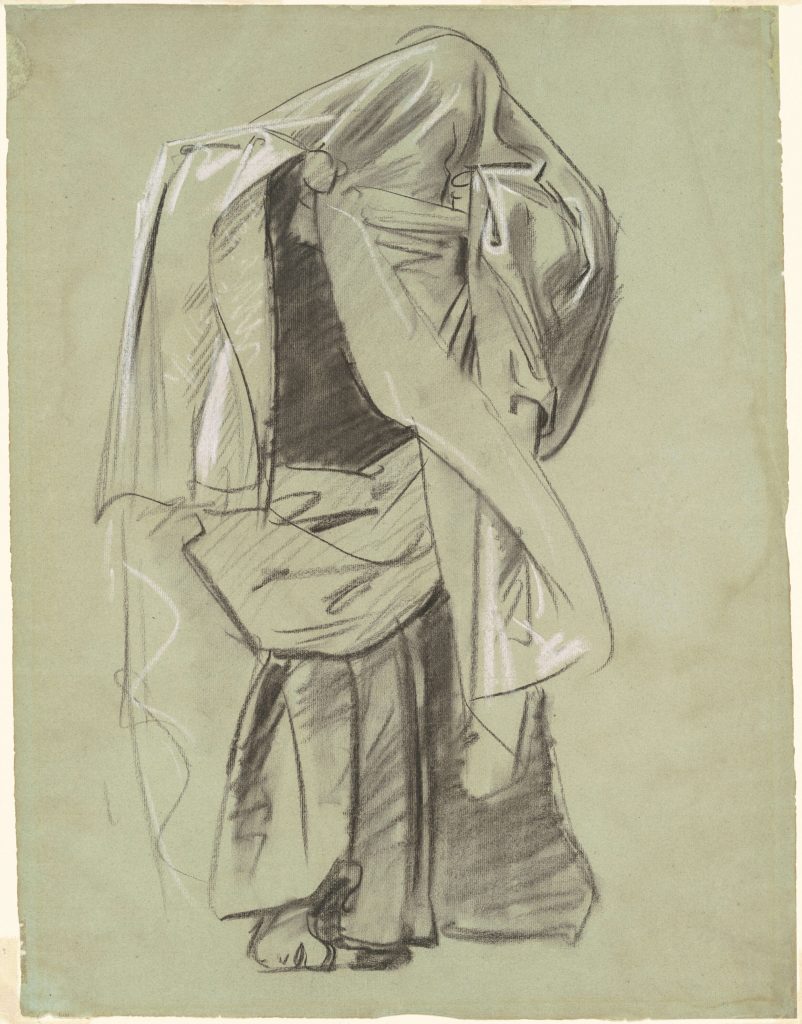

The great majority of Sargent’s drawings in preparation for larger artworks were studies for his three great mural projects at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston Public Library, and Harvard’s Widener Library. Chief among these are academic-style nude male figure studies for the profusion of allegorical figures he included in his murals. These studies focus on movement and anatomy – qualities we don’t otherwise see the artist strongly focus on in his other words. The resulting murals are highly classical in style and not much like the Sargent we know and love otherwise.

A 2020 exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (which owns some of these Sargent drawings) focused on Sargent’s studies of Thomas McKeller, an African-American hotel employee who was Sargent’s frequent model. McKeller’s form appears over and over again in Sargent’s MFA murals, though it is difficult to recognize when given white skin and a Caucasian face to portray Euro-American allegories. The exhibition pondered the dynamics between Sargent and his Black model, but solid answers were unfortunately elusive.

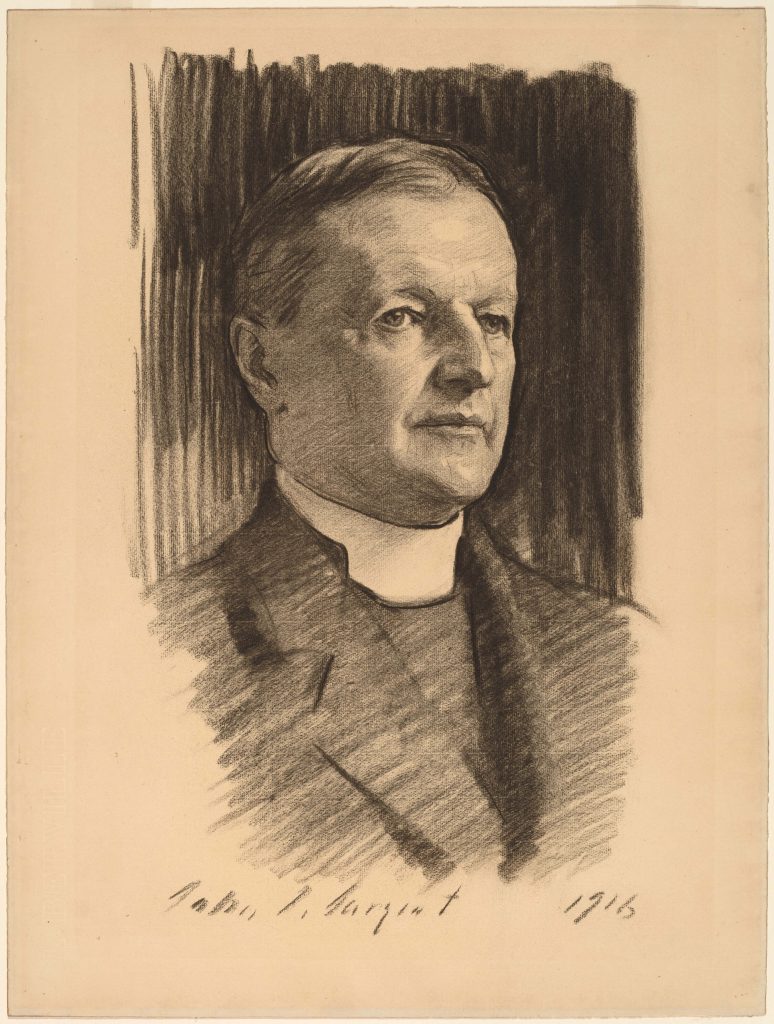

John Singer Sargent, The Rt. Reverend William Lawrence, 1916, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

When Sargent officially gave up portrait painting in 1907 to focus on his murals, he compromised with disappointed society figures by making charcoal portraits at a fraction of the price, effort, and time commitment. A selection of these portraits, many of which are in private hands and thus rarely displayed, appeared in a 2019-2020 Morgan Library exhibition. It was the first show to focus exclusively on this aspect of Sargent’s career.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Sybil Sassoon, 1912, charcoal. Private Collection, Photography by Christopher Calnan.

The charcoal portraits are fascinating. They represent many well-known sitters such as politicians, artists, writers, society figures, thinkers, and other prominent friends of the artist. Some drawings were commissioned and others were gifts. Although the charcoal portraits were the only type of Sargent’s drawings that were ever meant to be finished products suitable for display, they demonstrate a surprising range of styles and levels of finish. They often include a fascinating juxtaposition of detailed faces alongside clothing indicated by only the sparest of lines and gestures. Their backgrounds tend to be very minimal – either white pages left blank or wide swaths of bold black charcoal against which the faces stand out all the more dramatically. The chiaroscuro in Sargent’s charcoal portraits is generally spectacular.

John Singer Sargent, Study for “Frieze of Prophets”, 1890-1892, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Although the pandemic cut short the charcoal portraits and McKeller figure studies exhibitions, both still made strong points about Sargent’s drawings as worthy objects of enjoyment and study. We now have reason to hope that these drawings, especially the fascinating charcoal portraits, will soon take their places on permanent display alongside Sargent’s oil paintings and watercolors in the major museums who own them. With much to teach us about Sargent as an artist, they are much too compelling to ignore.

Patricia Hills: “A Portfolio of Drawings” in John Singer Sargent, New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1986, p. 251.

Richard Ormond: John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal, New York, The Morgan Library & Museum and Washington D.C., National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution in association with D Giles Limited, 2019, p. 7.

Hills, p. 259.

Holland Cotter: “John Singer Sargent’s Drawings Bring His Model Out of the Shadows“, The New York Times. May 7, 2020. Accessed 16 Sep. 2022.

Patricia Hills: “A Portfolio of Drawings” in John Singer Sargent, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1986.

Richard Ormond: John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal, New York, The Morgan Library & Museum and Washington D.C., National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution in association with D Giles Limited, 2019.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!