Summary

- The complex Hindu pantheon has a wide array of depictions of Parvati.

- Parvati is a manifestation of Shakti, the primordial life force of the universe.

- In most Hindu scriptures, the existence of Parvati is intrinsically intertwined with that of Shiva.

- Shakti manifested first as Sati, then as Parvati.

- Parvati raised the gods, Skanda and Ganesha, both consequential figures in Hindu mythology.

- Parvati appears in Hindu arts and iconography in various aspects, both benevolent and fearsome.

Shakti, The Primordial Energy

Shakti is the Sanskrit word for power, energy, or force. Hindu scriptures describe Shakti as the female form of Brahman (not to be confused with Brahma) and describe it as the primordial cosmic energy that gives rise to universes, sustains them, destroys them, and then repeats the cycle. Shakti is represented as a coiled serpent known as kundalini that exists at the base of the spine within each individual. In the theological tradition of Shaktism, Shakti is the dormant power that must be aroused in order to reach spiritual liberation or moksha. An understanding of the position of Shakti is essential to understanding the goddess Parvati, as Parvati is a manifestation of this higher cosmic being that is responsible for all dynamic forces in the universe.

The Manifestation of Sati

Shakti first manifested as Sati, daughter of the sage Daksha and granddaughter of Brahma, the creator. Despite the vehement disapproval of her father, Sati married the wild hermit god, Shiva, with his dreadlocked hair, and animal skin clothing. On one occasion, Daksha hosted a grand Hindu fire ritual known as havan and did not invite his daughter and son-in-law. Mortified at the disrespect shown to her husband, Sati threw herself into the ritual fire.1 Understandably so, Shiva was overcome with immense grief causing him to pull Sati’s lifeless body from the flames and engage in tandav, the ritual dance of destruction. As his violent dance threatened to destroy the entire universe, the god Vishnu cut Sati’s body into pieces to bring Shiva out of his delirium.

The Manifestation of Parvati

After losing his beloved, Shiva withdrew from the world and retreated into the Kailash mountains. Located in the western part of the Tibetan Plateau, Kailash is considered the axis of the universe and the place where the earth connects with the heavens. Here he entered a deep, trance-like meditation and cut himself off from the physical world. Concerned by his mental state and its grave implications, the gods coaxed Shakti to return to Shiva once more.

Shakti acquiesced and took form as Parvati, daughter of the mountain king, Himavan, and presented herself to Shiva to seek his companionship. Shiva remained oblivious to her presence and did not open his eyes despite Parvati’s insistent pleas. She then sought the aid of Kama, the god of desire who had the power to evoke lust with an arrow (parallel to the Greek Eros or the Roman Cupid). However, when the arrow struck Shiva, it did not have the desired effect. Shiva opened only his third eye and expelled a fiery beam that incinerated Kama.

Parvati’s Penance (Relief Panel), ca. 8th century, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.

Parvati as Aparna

In order to prove her earnestness, Parvati decided to match Shiva’s energy and perform rigorous penances or tapasya. Thus she gave up her worldly comforts and like Shiva, retreated from the physical world. Over time she mastered her physical needs, including shelter and nourishment. She wore no clothing to protect herself from the harsh weather and ate nothing to sustain herself, not even a leaf. Impressed by her devotions, the forest ascetics named her Aparna, the leafless one.

The power of her tapas pleased Shiva and drew him out of his mediation. He stepped out of his cave and accepted Parvati as his wife. Shiva and Parvati married in the presence of the gods and upon Parvati’s request, Kama was resurrected.

Marriage of Shiva and Parvati, ca. 9th century, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Parvati as Ambika

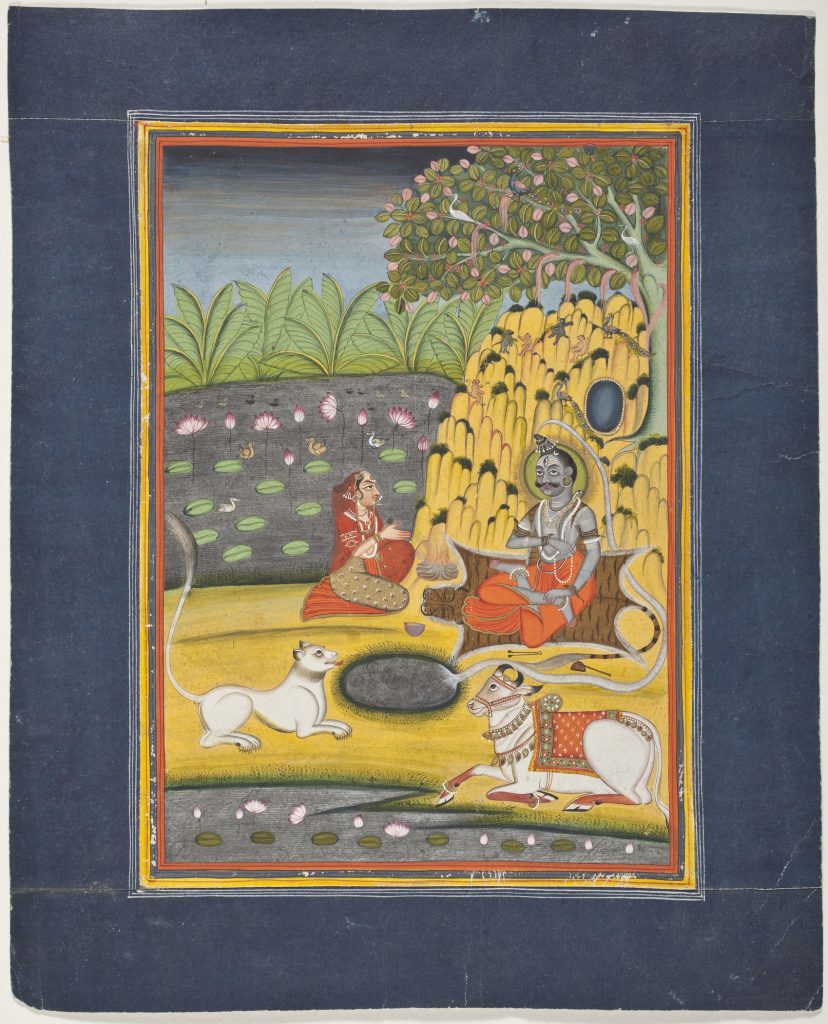

The divine couple spent their days on the banks of Lake Mansarovar and made it their marital home. Tantric literature describes the dialogue between Shiva and Parvati during this period, with Shiva adopting the role of a teacher and Parvati of a student. Parvati inspired Shiva’s concern for the state of the world, while Shiva revealed to her the truth of the Vedic scriptures that he had mastered through meditation and austerities. The blissful union of Shiva and Parvati represented the harmony between matter and spirit and in this form, Parvati is known as Ambika, the goddess of family, marriage, and motherhood.

Parvati Worshipping Shiva, ca. 1750-1800, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

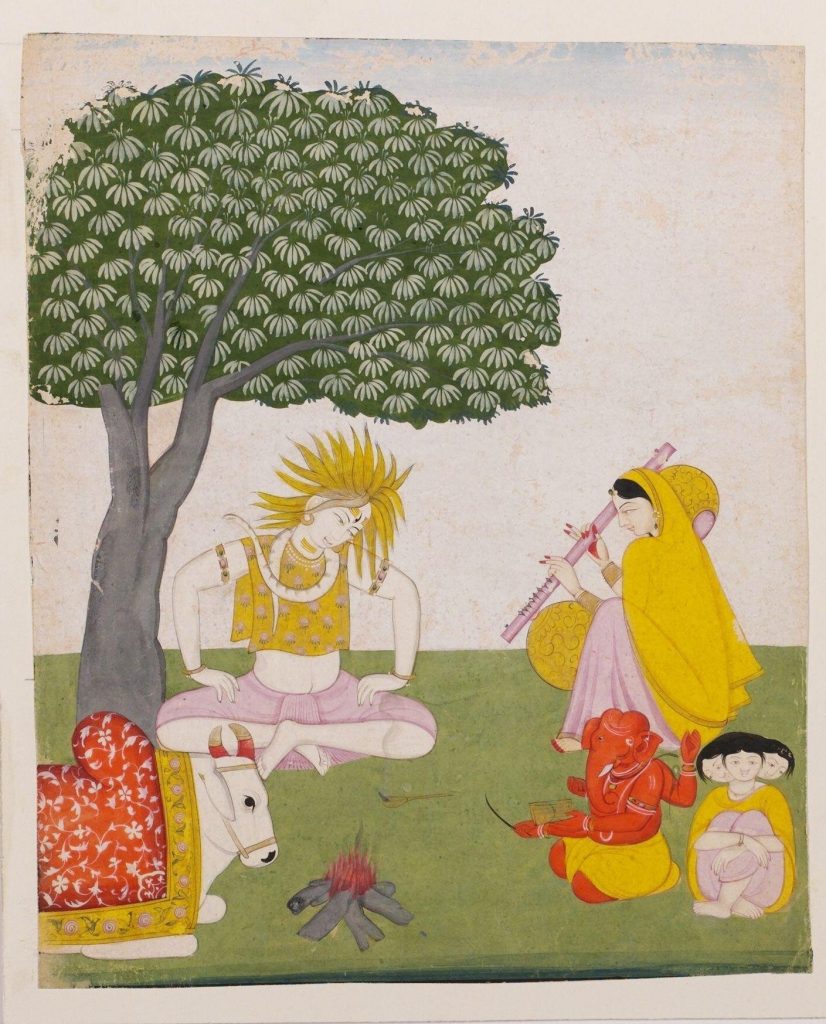

Skanda, The Guardian of the Heavens

Some Hindu scriptures consider the warrior god, Skanda, to be the son of Shiva and Parvati. The Mahabharata texts, detail one occasion when Shiva and Parvati were disrupted while having sexual intercourse causing Shiva to inadvertently spill semen on the ground. The semen was incubated in the holy river Ganges and preserved by the heat of Agni, the god of fire. Thereafter, Aranyani, the goddess of the forest, embedded the divine seed in the fertile forest floor where the seed became a lotus that then transformed into a child. This child with six heads and twelve arms was nursed by forest nymphs, or Krittikas before being raised by Parvati who instructed him in the art of war.

Skanda, a popular god in southern Indian tradition, took command of the celestial armies and defeated the powerful demigod, Taraka, in battle, thereby restoring power to the gods.

Shiva, Parvati, Ganesh, and Karttikeya, ca. 1760, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.

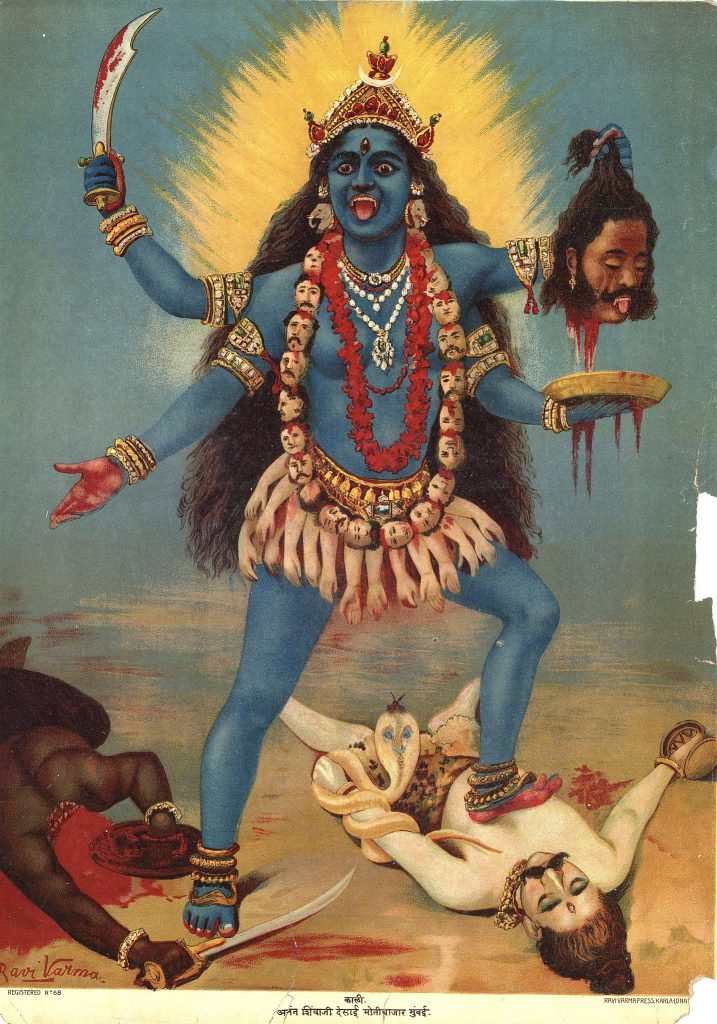

Parvati as Kali

Although Skanda proved immensely successful against most warring demigods, he was at a disadvantage against the vicious Raktabija. Raktabija had a divine power that caused droplets of his blood to spring to life as demigods as soon as they touched the ground. In order to aid her son, Parvati entered the cosmic battlefield as the fearsome warrior goddess Kali.

Kali spread her supernatural tongue across the battlefield and caught each droplet of Raktabija’s blood before it could touch the ground. Without the ability to multiply his numbers, Raktabija was left powerless and Skanda prevailed.

The Hindu Goddess Kali, Jackwood Sculpture with traces of paint, ca. 17th century, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

The Taming of Kali

Intoxicated by Raktabija’s blood, Kali danced wildly on the battlefield wearing a terrifying garland of severed heads and a girdle of severed hands. Blinded by bloodlust, she danced across the three worlds and destroyed all that was in her path. In order to restrain her, Shiva took the form of a corpse and blocked her path. Kali tripped over his lifeless body and was jolted out of her frenzy. She brought her husband back to life. Shiva then took the form of a child and began to cry, stirring maternal love in the heart of Kali and causing her to adopt the form of Gauri, the radiant mother, and giver of life.

Kali Trampling Shiva, ca. 1910, Chromo lithograph. Google Arts & Culture.

The Birth of Ganesha

Despite Shiva’s lack of inclination to grow his family, Parvati was determined to be a mother and decided to do so without Shiva’s involvement. On one occasion when Shiva was away, the determined goddess scrubbed herself with sandal paste that scrapped off the dead skin. She then mixed the dead skin with clay and molded it into a child into whom she breathed life. She asked her new progeny to keep watch over the cave as she rested.

Upon his return, Shiva found a strange child unknown to him that prevented him from entering his own home. Enraged, Shiva raised his trident and beheaded the young Ganesha. Parvati was understandably furious at the murder of her child and threatened to destroy the whole world. To placate her, Shiva brought Ganesha back to life by placing the head of an elephant on Ganesha’s severed neck and then accepted him as his son. Ganesha, the keeper of Parvati’s threshold, became the remover of all obstacles in Hindu tradition. He is commemorated before embarking on any new journey and is worshipped before all other gods.

Parvati and Ganesha, ca. 1890, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.

The Combined Depictions of Shiva and Parvati

Perhaps the most popular and widespread symbol in the Hindu world is that of the Shivalinga. In this form, Shiva is represented by linga, a phallic structure that represents regenerative power, while Parvati is symbolized by a yoni, the womb. The linga-yoni are always depicted together and represent the interdependence and union of feminine and masculine energies.

Shiva and Parvati have also been expressed in the form of Ardhanarishvara, where half the body depicts Parvati while the other half depicts Shiva.

The Androgynous Form of Shiva and Parvati (Ardhanarishvara), ca. 1000, Los Angeles Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Diverse Iconography of Parvati

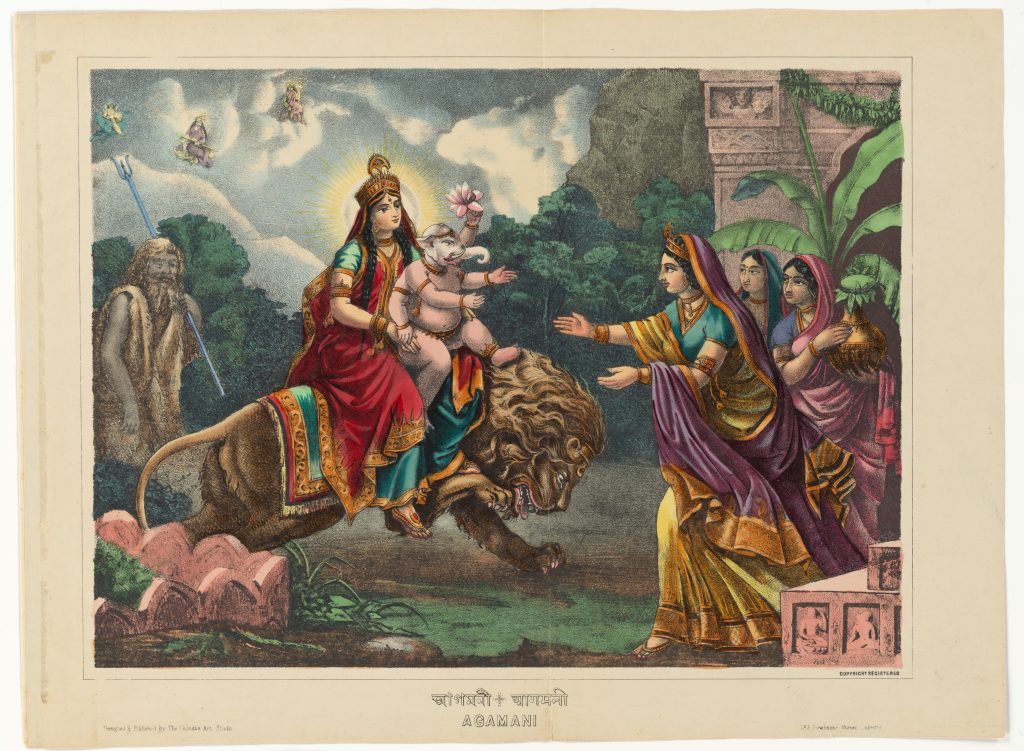

Generally, the figurative portrayals of Parvati in art are overwhelmingly intertwined with the depictions of Shiva. In her nurturing and benevolent aspects, Parvati is depicted as the adoring and devoted consort who is placed close to Shiva or on his lap. Sometimes these depictions include either Ganesha, Skanda, or both. In most portrayals, she wears fine (often red) clothing and grand jewels. Her animal companion or vahana is the lion, though in some works Nandi the bull, the vahana of Shiva, may also accompany her.

When accompanied by Shiva, Parvati is depicted with two arms, but when depicted independently, she is generally depicted with four. The hands may either express symbolic gestures or mudras, or may hold the various attributes associated with Parvati, such as a mirror, a bell, a citron, prayer beads, or a lotus flower.

Uma-Maheshvara (Shiva and His Consort Parvati), ca. 13th century, Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY, USA.

In her destructive and ferocious aspect as Kali, the goddess is apparent in her recognizable blue skin. She is described in a fearsome form and a frenzied delirium, complete with disheveled hair and red, bloodshot eyes. In this form, she is generally depicted atop the lifeless corpse of Shiva. Given the complexity of Hinduism and the diverse regional variations, the many forms of Parvati vary greatly when interpreted by different schools of thought, regions, and local cultures.

Agamani, ca. 1878–1883, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.