Summary

- Carlo Crivelli was born in Venice and settled in Eastern Italy where he developed his unique style.

- His religious paintings were mostly forgotten but re-emerged in art history discourse after the Pre-Raphaelites took interest in him.

- Crivelli questioned the very nature of painting. His art is theatrical and enigmatic.

- The artist experimented with odd perspectives and illusion. He added gold leaf and even jewels to his works. One of the most enigmatic symbols used by Crivelli was a cucumber included in many of his religious paintings.

- Crivelli used mind-bending conventions similar to 20th-century Surrealists. His works play with the viewers, art history conventions, and iconography.

The Sailor’s Wife

Carlo Crivelli was born around 1430 in Venice, Italy. We know he worked as a painter, sometimes collaborating with his younger brother, Vittorio Crivelli. But the next significant event officially recorded was worthy of the gossip columns of Venice: Carlo Crivelli was arrested for adultery. He spent six months in jail for co-habiting with Tarsia, the wife of a sailor.

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child, 1482, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

Now, as the daughter of a merchant seaman, I must admit my sympathies lie with Carlo and Tarsia. The life of a sailor’s wife is hard, alone for much of the year, eking out a meager living as much of the sailor’s wage is spent on liquor in far-flung ports. Is it too much to imagine Tarsia hungry for food and intelligent company, meeting the brilliant young local painter and falling for him? I wonder if it is Tarsia’s face we see on Crivelli’s Madonnas? But enough of the romantic speculation, back to the facts.

Carlo Crivelli, Saint Mary Magdalene, c. 1491-1494, National Gallery, London, UK.

Self-Exile from Venice

We know that Crivelli left Venice in 1458, as soon as he was released from jail, and he never returned. Perhaps he felt slighted by his hometown, snubbed and shamed by the judgment of society. To this day, Venice has only two pieces of Crivelli’s art on display in the church of San Sebastiano – that relationship certainly stayed sour for centuries. Crivelli settled in the Marche region of eastern Italy, and it was here that he developed his singular style of religious paintings.

Carlo Crivelli, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1491-1494, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Monastic Favorite

In 1490, Crivelli was knighted by Ferdinand II of Naples. During his life, he produced over 30 works, all of them religious. He made a name for himself producing tempera paintings on wood and altarpieces for monastic orders, and he was essentially the most important painter of the region. He died in 1495 and was promptly forgotten. His contemporaries, such as Giovanni Bellini or Raphael are known as artistic superstars across the globe, but it was not until the 19th-century Pre-Raphaelites took a liking to Crivelli that his name re-emerged from the annals of art history.

Carlo Crivelli, Virgin and Child, c. 1480, V&A Museum, London, UK. Detail.

The Crazy Knight and His Fruity Festoons

Crivelli doesn’t want you to be lost inside his paintings, he wants to talk to you about painting. He is questioning the very nature of painting. You cannot just observe a Crivelli. You have to get inside it, wander around, then crawl out and think about what you’ve seen. This artist wants you to think critically, and respond to him. We see the astonishing beauty of the Madonna, but look, she has a wooden rod of mixed fruit hung just behind her head, and we can see the knotted string holding it up.

Carlo Crivelli, The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele, 1489, National Gallery, London, UK.

The face of a saint is filled with love and loss, but look, his dirty gnarly toes are hanging over the edge of the painting, poking out at us. We are lost in the forest with Saint Gabriele, but then look, there is a giant head hiding in the shrubbery and enormous fruit floating in the sky. It is a dizzying experience. Crivelli transports us with a beautifully executed Italian summer sky, whilst telling us, at exactly the same time, “this is a painted sky”. It is deliberate, theatrical, and enigmatic.

Carlo Crivelli, The Vision of Blessed Gabriele, c. 1489, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Camp Playfulness

Adding 3D objects to paintings was unusual at this point in art history. Crivelli added gold leaf, gesso, and even jewels and real keys as he worked on his paintings. We look at the Madonna and see that she has actual pearls and glitter on her head. It’s like when kids glue pasta shapes into their school art projects. There is the reality of the pasta and the imagination of the artwork. Crivelli experiments with odd perspectives, and trompe l’oeil throughout his work. He is a witty painter, contrasting actual reality with spiritual reality. Centuries later, writer Susan Sontag refers to this as “early camp” – it is an earnest and elegant act, but done with playfulness and subversion. It energizes the visual experience and is an invitation from Crivelli to respond.

Camp is the paintings of Carlo Crivelli, with their real jewels and trompe l’oeil insects and cracks in the masonry.

Notes on Camp, 1964.

Cryptic Cucumbers

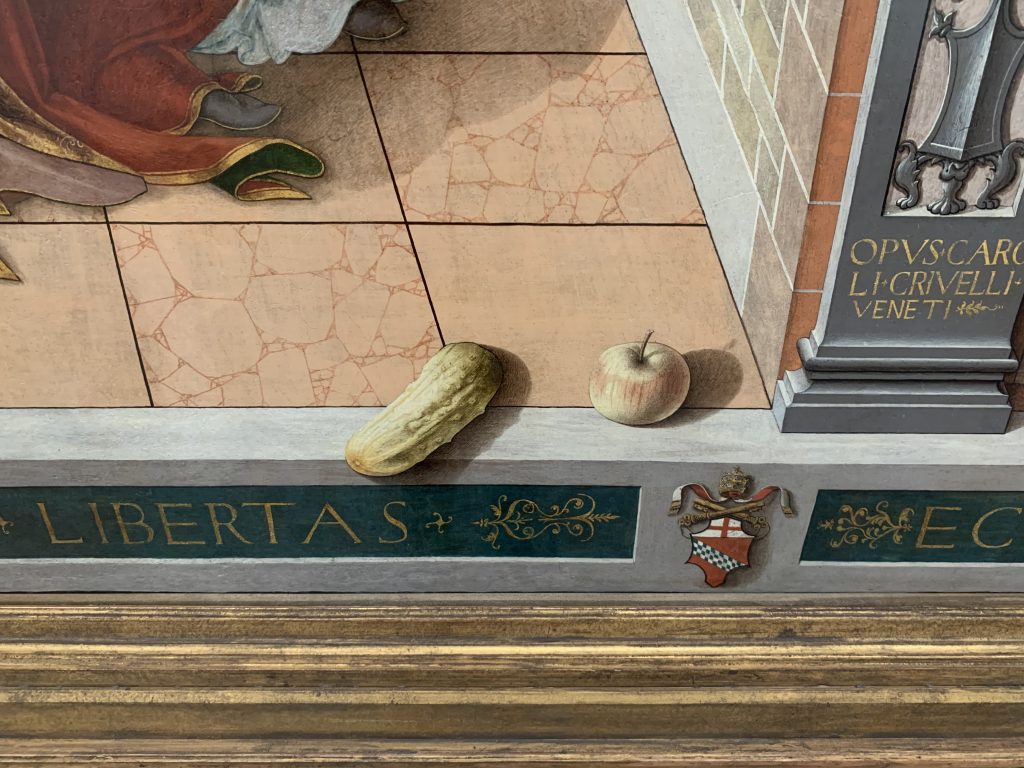

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

The cucumber appears so many times in Crivelli’s paintings – not a fruit we would usually associate with religious imagery. But it has come to be something of a signature motif for this Renaissance Italian painter. Botanical symbolism is common in religious art. The apple is commonly used in religious paintings – it can represent a woman, Eve or sin. Or it might be knowledge and wisdom. This we know. But in Crivelli’s case? Fruit isn’t so simple. Art historians (and food historians) haven’t been able to come to firm conclusions on the Crivelli cucumber.

A distinct lack of ecumenical cucumber experts means we will never really know whether the cucumber so often found in a Crivelli painting represents man (and sin) or spiritual Christ (and redemption), or physical Christ (and his human genitalia), or as some suggest, the fruitfulness of Mary. Maybe Crivelli just loved cucumbers. Writers’ side note: The Western Journal of Health carried reports of a certain Captain Megrim in the USA in 1831 who mounted a crusade against cucumbers, believing them to be dangerous to life and spirit. Unconnected to Crivelli, yes, but it proves just how contentious the humble cucumber can be.

The Susan Collis Response

Susan Collis, 100% Cotton, 2004 and Dead To Me, 2011, Shadows on the Sky, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK. Photo by the author.

In 2022, A Birmingham Ikon Gallery presented the first exhibition in the UK dedicated to the work of Crivelli. Shadows on the Sky exhibition highlighted the illusionism in Crivelli’s paintings but also included an installation by contemporary artist Susan Collis. What looked like discarded curatorial or cleaning materials, were in fact carefully upcycled objects, standing in stark contrast to the Crivelli works. For instance, we could see a discarded broom, but on close inspection, it was set with jewels and pearls. Paint spattered overall was actually embroidered with fine silken threads.

This was a brave installation. I did see visitors either walking straight past, or assuming the gallery space had not been cleared properly. But it was very Crivelli – it had wit, it raised the humble everyday object to preciousness, and of course, involved mixed media. Collis celebrates expert, labor-intensive crafting techniques, overlaying them onto humble materials, inviting us to take a closer look.

The First Surrealist?

We can argue about when Surrealism first started. André Breton wrote the Surrealist manifesto in 1917, inspired by paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, and the movement grew exponentially through the 1920s and 1930s. But wait a minute, wasn’t Crivelli using many of the same mind-bending conventions way back in the 15th century?

Carlo Crivelli, Madonna and Child, 1482, Vatican Museums, Vatican City. Detail.

My evidence: A life-size fly sitting next to a Madonna. Giant fruit hanging in the sky, casting shadows. A light that beams like a laser from the sky, through a window into a woman’s head. A tiny saint kneeling at the feet of a giant Mary and child. Oversized gourds, apples and cucumbers, resting precariously on the edge of a painting, poking out of the frame. A model of a city resting inside an actual city. Was this the Renaissance Magritte? In reality, Crivelli is considered part of the international Gothic style, but hints of surreal and conceptual art abound, 500 years before Dali got in on the act.

Saint Emidius

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486, National Gallery, London, UK.

In Crivelli’s hands, hackneyed and over-done subjects become something new and exciting. We are never likely to run out of Renaissance paintings of the Annunciation, or the Madonna and Child, but Crivelli makes his subjects and his symbols multi-task, as in the enormous masterpiece The Annunciation with Saint Emidius of 1486.

Crivelli follows typical Annunciation iconography – the Virgin Mary is placed on the right of the painting, the Angel Gabriel arriving on the left. But then Crivelli adds in a third figure, Saint Emidius, carrying a model of the local town, setting the Annunciation very firmly in Ascoli Piceno, Italy, not Nazareth. Is Emidius asking Gabriel to bless some town planning while he is here?

We have typical, traditional symbols – the peacock for immortality and resurrection, the goldfinch in a cage for Christ’s sacrifice and redemption, the apple as forbidden fruit. But even here there are tricks and wit. The apple balances on a stone wall at the front of the painting, as if we could just reach in and take a bite – well if it wasn’t forbidden of course. Next to the apple, a large, knobbly cucumber pokes directly out towards us.

Crivelli presents us with a domestic interior, and mundane urban street activities. But alongside these very ordinary events, we have intense spiritual, supernatural events. Here is the meek Virgin, kneeling in prayer indoors, being impregnated by the Holy Spirit, shown as a ray of light and a dove. The divine ray of light from heaven is an intense golden gash, which cuts the huge canvas in half, totally disrupting the domestic scene as well as the illusion of perspective.

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486, National Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Playing with Reality

Every painting by Crivelli seems slightly eccentric, but always intelligent and playful. Like the Spiderman Multiverse, we are presented with multiple layers of “reality”. Carlo Crivelli’s work is cryptic and full of riddles (remember those cucumbers). But above all, it is beautiful, and fully deserves its place in art history. The Ikon Gallery had created an absolute gem with their Shadows on the Sky exhibition, and I am glad to have witnessed it.

Audrey Flack, Madonna Della Candeletta, 2021, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK.

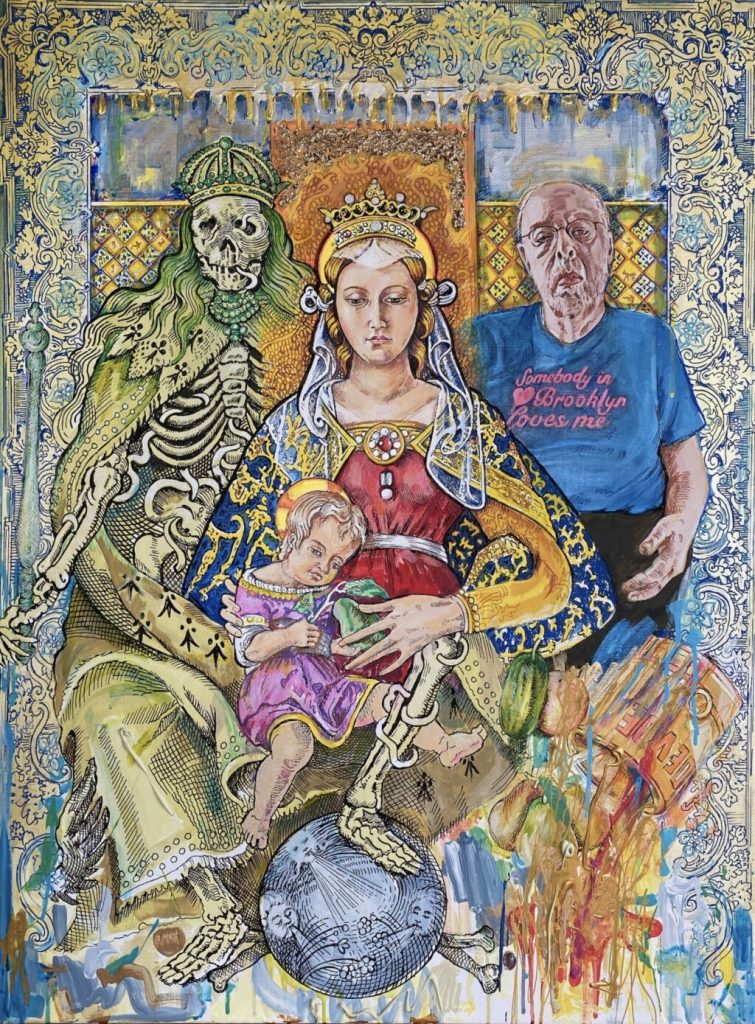

After Crivelli: Audrey Flack

To coincide with Shadows on the Sky, Ikon Gallery was showing two paintings by pioneering photorealist artist Audrey Flack. These could be discovered in a tiny gallery space, The Tower Room, above Shadows on the Sky. In 1981, American Flack wrote an article for Arts Magazine recognizing Crivelli’s impact on contemporary art. Pollock’s Cans from 2016 is based on Crivelli’s Pietà from 1476, whilst a very recent painting combines a portrait of Flack’s husband with the Crivelli Madonna Della Candeletta painting of 1490.

It is the original artist, the one who breaks the rules, the eccentric, the maverick, who should be more carefully considered, and not cast aside, because he or she doesn’t fit into the mainstream of a movement. One should not be punished for being unique – and yet this has been the case.

Shadows on the Sky, Ikon Gallery, 2022, exhibition catalogue.