1. Self-Portrait

Anna Ancher (1859–1935) was born Anna Brøndum. Her family ran the grocery store and hotel in Skagen, on the remote northern point of Denmark, and she was brought up surrounded by the many artists and writers who came to visit the town. Famously, Hans Christian Andersen was staying in the hotel on the night she was born. From the 1870s, Skagen was an artist’s colony, which attracted those looking for traditional subjects, an unspoilt landscape, the chance to paint plein air (outside), and a cheap place to live.

Ancher’s talent was spotted early and, encouraged by her mother, she spent three years from the age of 16 studying art in Copenhagen. In 1888–1889, she visited Paris, where she worked under Puvis de Chavannes and discovered the art of the Impressionists. Her biggest support and influence, however, came from her husband. Michael Ancher, also a painter, first came to Skagen in 1874. The couple married in 1880, and despite Anna becoming a mother three years later, Michael continued to support her artistic career.

Although Ancher was painted many times by her husband and other Skagen artists, notably Peder Krøyer, this is her only known self-portrait. It shows her aged about 18, intense and slightly severe, and utilizes the dark, realist palette of her early career. There is nothing showy or idealized: Ancher is happy to record her crooked nose, which she had broken as a child.

2. Skagen Realism

Many artists were drawn to Skagen because of the traditional way of life they found there among its fishing and agricultural community. Members of the colony, like those at Newlyn, Cornwall, had studied in France and soaked up the style and subject matter of both Jean-François Millet and Jules Bastien-Lepage.

Ancher uses an earthy palette and an intense close-up to show an old man carving a piece of wood. He is engrossed in the task, oblivious of us, despite being posed by the artist. The angled light, coming from a window off canvas to the left, illuminates his characterful, concentrating features. Both his face and hands are gnarled and roughened by decades of outdoor labour. The dark palette and careful recording of detail are like that of her self-portrait, but both would be abandoned later in Ancher’s career.

As a local, Ancher knew many of her sitters personally, and sometimes named them in her works as she does here. Whereas other Skagen painters represented “types,” she focused on portraying specific individuals.

3. Discovering Color

The Maid in the Kitchen takes an everyday, domestic setting, painted in a deliberately rough and ready style. Much of the palette is a subdued combination of grubby whites and browns, but the central dominance of the woman’s red skirt creates a warmth. The diffused sunlight is not used here to illuminate the scene—it rather emphasizes the dinginess of the interior and throws the figure almost into silhouette. It does, however, create warmth, creeping under the doorway and through the billowing curtain, which provides the only sense of movement.

The still simplicity is reminiscent of Dutch 17th-century interiors—Johannes Vermeer used side-placed windows to create the same sense of calm concentration. The subject of domestic labor in a poor home is one seen in other Skagen artists’ works. The quiet introspection and the figure who is disengaged from the viewer, however, would become recognizable tropes throughout Ancher’s career.

4. Seeing the Light

Ancher’s focus on domestic interiors inevitably meant that she depicted women at work, involved in household tasks. This scene shows how those tasks were passed down through the generations, with a seamstress teaching two young girls to sew. Again, it is an intimate yet introverted scene, which the viewer witnesses but from which we are also excluded: the girls have their backs to us, the teacher is intently looking at their work.

The angled light here takes on a more significant role, not simply illuminating or warming, but almost gilding the girl’s blonde hair and the front of the woman’s blouse. The plant casts a complex shadow on the plain wall, and one senses that this patterning is as much Ancher’s focus as the narrative. Whilst the figures are static and rendered with a casual lack of detail, the light seems alive and full of movement.

5. Solidifying Color and Light

The Blue Room was part of the Brøndums Hotel and is featured in many of Ancher’s paintings. Here, her daughter, Helga, is knitting or crocheting, engrossed and oblivious of the viewer, in much the same way as the girls sewing in the previous work. However, it is the room itself which is the real subject with its rich blue walls, into which the girl’s smock merges, and a strongly receding striped rug which dominates the center foreground.

Even more significantly, the angled light from the window has a tangible physicality. The shapes created on the back wall are heavily painted and the sun literally slices through the patterning of the rug. It creates brushwork blotches on Helga’s back and one contemporary critic complained it was eating up Helga’s hair. The rich color, particularly the juxtaposition of blue with the orange curtains, and visible paint marks show the impact of Impressionism. However, Ancher is also starting to see the interior as a series of abstracted forms. Whilst the Impressionists sought to break up light into prismatic color, she seeks to solidify it.

6. Community

Many of the Skagen artists produced large-scale group paintings which highlighted traditional tasks and the community spirit of a place that felt as if it was untouched by modernity. They also produced similar works which celebrated their artistic community, most famously Krøyer’s Hip, Hip, Hurrah, which features portraits of Anna and Michael Ancher. Such scenes are less common in Ancher’s work, despite her well-known A Vaccination and several interiors showing people plucking geese.

A Field Sermon shows the townsfolk of Skagen listening to a preacher. Cold greens and greys and a preponderance of black create an unwelcoming, windswept hillside. The scene is devoid of Ancher’s usual sunlight, which is relegated to a triangle of beach in the top left. There is little sense of comradeship amongst the huddled masses, each isolated either by their rapt attention or their boredom.

Ancher’s personal rebellion against her strict religious upbringing perhaps explains some of this negativity. However, it was a painting she put a great deal of work into: a number of preparatory sketches survive. This was clearly a determined attempt to match herself against her fellow Skagen artists.

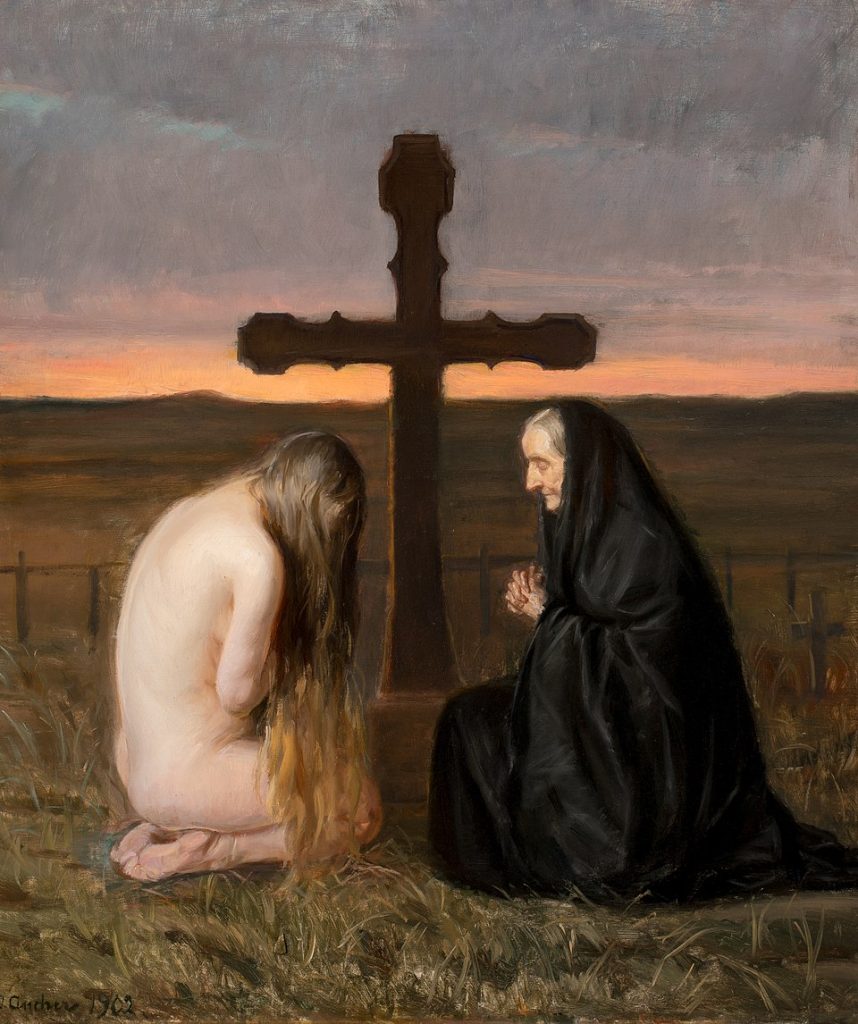

7. Symbolism

Ancher also tackled religion in Grief, a highly unusual painting, apparently based on a dream. It features a young, naked woman and an older figure, modeled on the artist’s own mother, kneeling on either side of a cross. A bleak landscape gives way to a flat horizon illuminated by the pinkish glow of a sunset. The women appear to be praying together. The lowered head of the younger figure implies she is perhaps seeking forgiveness; perhaps she is a vision manifested from the prayers of the older woman.

Ancher was familiar with European symbolism not just through her studies with Puvis de Chavannes. She and her husband had traveled extensively during the 1880s; she exhibited widely, including London, Paris, and even Chicago. The Skagen artists and writers were part of what is known as the Modern Breakthrough, which was revolutionizing Scandinavian culture. Most importantly, Ancher herself was always experimenting.

Death is a constant poignancy within her work. She recorded a funeral and painted a street in Skagen dedicated to locals who had lost their lives trying to help a sinking ship. Most poignantly of all, she painted her mother grieving the loss of Anna’s sister, and a few years later sketched her mother on her deathbed.

8. Breezy Impressionism

Ancher was not just a painter of light indoors. She regularly sketched the countryside and coast around Skagen, and painted the town itself. Harvesters literally zings with sunshine, using a deliberately limited palette; just blue, yellow, and white, and a simple composition to evoke high summer in the fields. The strong horizontal division and almost complete lack of depth give the figures a slightly unreal quality and the presence of the scythe, a traditional symbol of mortality, suggests perhaps we could read a deeper meaning within the scene.

On the other hand, Ancher’s broad brushstrokes and carefully positioned color blocks create a lively immediacy. The verticals of the wheat stalks are swaying slightly in the wind, the patches of white clothing move our eye across the canvas against the puffy clouds behind. Strong dark diagonals created by the tools add further movement. The effect is a clever balance between a witnessed moment and a sense of timeless, repeated, meaningful labor.

9. Experimentation

Throughout her career, Ancher pushed the boundaries. Many of her works, like Evening Sun in the Artist’s Studio, were never exhibited during her lifetime. A group of minimalist landscape sketches was only discovered in 2014. Here, the exploration which she had started in The Blue Room is taken further: all narrative subject matter has been removed, leaving only color and light. The solidity of the room itself seems unimportant. The corner is barely defined as a right angle, the walls seem to bulge and sway. The furniture is treated as a series of abstracted silhouette shapes.

What interests Ancher here is light. It is painted in heavy impasto, vibrantly colored in oranges, reds, and pinks. The window panes create a tangible grid on the wall. The light itself infuses the whole space, blushing the blue walls with hints of pink, oozing peachy-orange across the floor.

10. A Woman at Peace

Anna Ancher is a difficult artist to pin down. Her life story, that of the local girl who married a painter, underplays her talent, her determination, and her originality. Her association with Skagen leads to a focus on quotidien domestic interiors, which is ultimately uncharacteristic of her work as a whole. She was a painter of old age and death, but without Edvard Munch’s morbidity. In her many images of friends and family, like this painted in her own garden, she represents a comfortable, contented existence, full of life and light. However, as so often in her work, we are kept at a distance by the sketchiness, the sea of flowers in the foreground, and the figure’s refusal to meet our gaze.

Restless and ever-changing, Anna Ancher’s work is almost as elusive as the light she so loved to paint. It is also as positive and illuminating. This Danish woman deserves her place in the sun.

If you want to see Ancher’s work in person, Anna Ancher: Painting Light is on show at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until March 8, 2026. Skagens Museum holds the largest collection of her work.