Fanny Eaton—Pre-Raphaelite Muse from Jamaica

Fanny Eaton was a regular model for the Pre-Raphaelites during the 1860s and features in a number of famous works. Yet for most of the last century,...

Catriona Miller 19 February 2026

For centuries, artists interpreted the biblical story of Salome and turned it into a lasting theme in art. But where did this fascination come from? And what spurred a radical transformation of her character? Read on to find out!

The real Salome was a 1st-century Jewish princess. Her stepfather was Herod Antipas (not to be confused with his more infamous father, Herod the Great). He was regent of the region of Galilee in Palestine, which was at that time under Roman control. Very little is known of Salome, but she rose to fame thanks to her depiction as a key character in the famous biblical episode of the beheading of John the Baptist.

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Feast of Herod and the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, 1461–1462, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

According to the New Testament, Salome danced for her stepfather and his guests at a dinner party for his birthday. So pleased was Herod with Salome’s performance that he granted her a wish. Coerced by her mother, Herodias, Salome asked for the head of John the Baptist. Reluctantly, Herod agreed.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Feast of Herod, c. 1635–1938, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh, UK.

In the Bible, Salome is a victim of her mother’s scheming. She has no interest nor taste for the violence that was to follow. Herodias’ growing resentment towards John the Baptist (who had criticized her marriage to Herod) was the driving force behind the beheading, with Salome being an unwilling and unknowing participant.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist, 1610–1615, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary.

Most of the early artistic interpretations of the episode align with this version of the story. Caravaggio’s Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist is a prime example. Like many before and after him, Caravaggio (1571–1610) chose to represent the moment Salome is given the head of John the Baptist by the executioner. Her expression is one of distaste, with her eyes looking away from the severed head. In contrast, the artist added Herodias in the background, smirking at the success of her plan.

While this portrayal is an example of the simplistic characterization of women as either evil or virtuous, it contains none of the eroticized and exoticized elements that came to characterize Salome’s story in future portrayals.

Caravaggio, Salome Receives the Head of John the Baptist, c. 1609–1610, National Gallery, London, UK.

In the 19th century, the story and character of Salome underwent a radical transformation—from unwitting victim to bloodthirsty, uninhibited temptress. Artists found in her the perfect image through which we can see very timely topics of the day: from the fascination with the East and its depiction as a land of magic and mystery (as opposed to the more civilized, rational West) to the fears around the growing independence of women in society and the sexual liberation that follows.

This shift toward a prototypical femme fatale is shaped by the work of three very different artists: French symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, German composer Richard Strauss, and literary master Oscar Wilde.

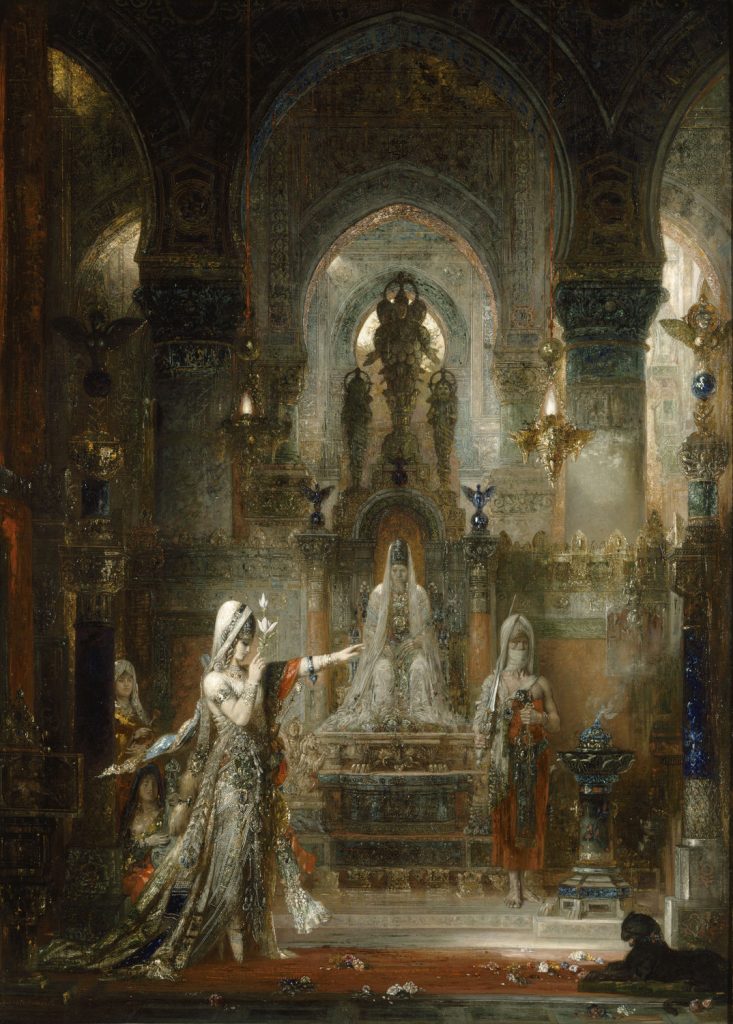

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing Before Herod, 1876, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Gustave Moreau (1826–1898) started it all. He was very interested in the myth of Salome and created several artworks (paintings, but also sketches and drawings) connected to the biblical episode. The most famous one is his 1876 Salome Dancing Before Herod.

Here, Salome is portrayed as a mystical, almost magical creature, as she dances to entice Herod to have her wish to have John the Baptist killed granted. All of Moreau’s Salomes are either dressed in revealing, lavish clothing or entirely naked—his interpretation turned Salome into a rather different figure than what had been generally portrayed in previous centuries.

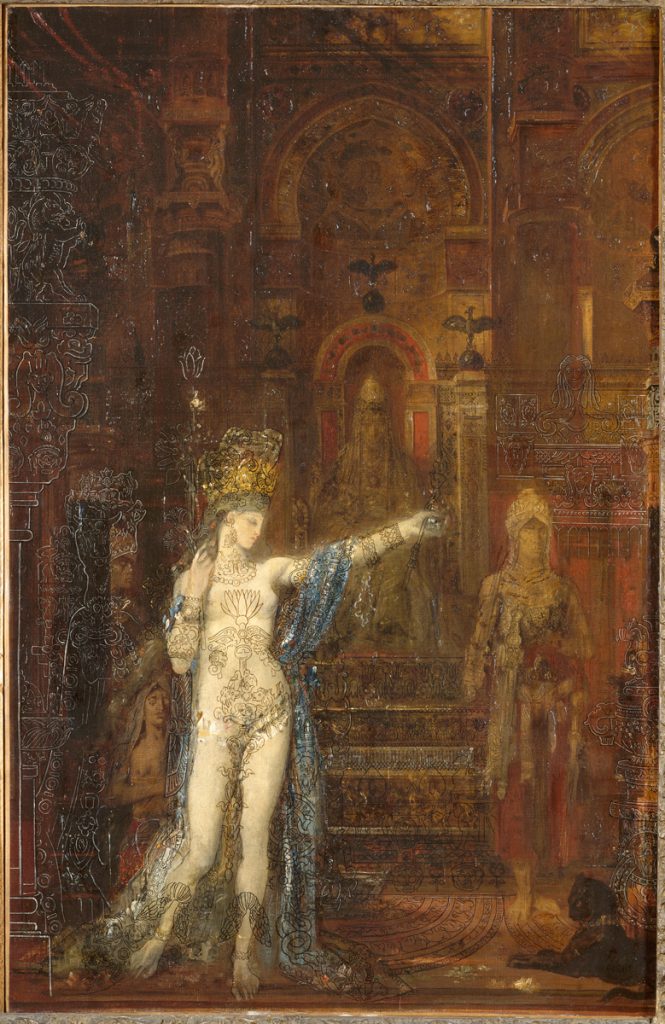

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing (Salome Tattooed), 1874, Musée national Gustave Moreau, Paris, France.

In 1893, Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) published Salome, a one-act play centered around the events leading to and resulting from the beheading of John the Baptist. Wilde dramatically rewrote the story. Salome became a disarmingly beautiful woman. She was lustfully attracted to the saintly John the Baptist, who refused her. As she danced for Herod, she used her stepfather’s infatuation with her to ask for John the Baptist’s head. She kissed it incessantly to quench her lust before Herod, in disgust, ordered his army to end her life.

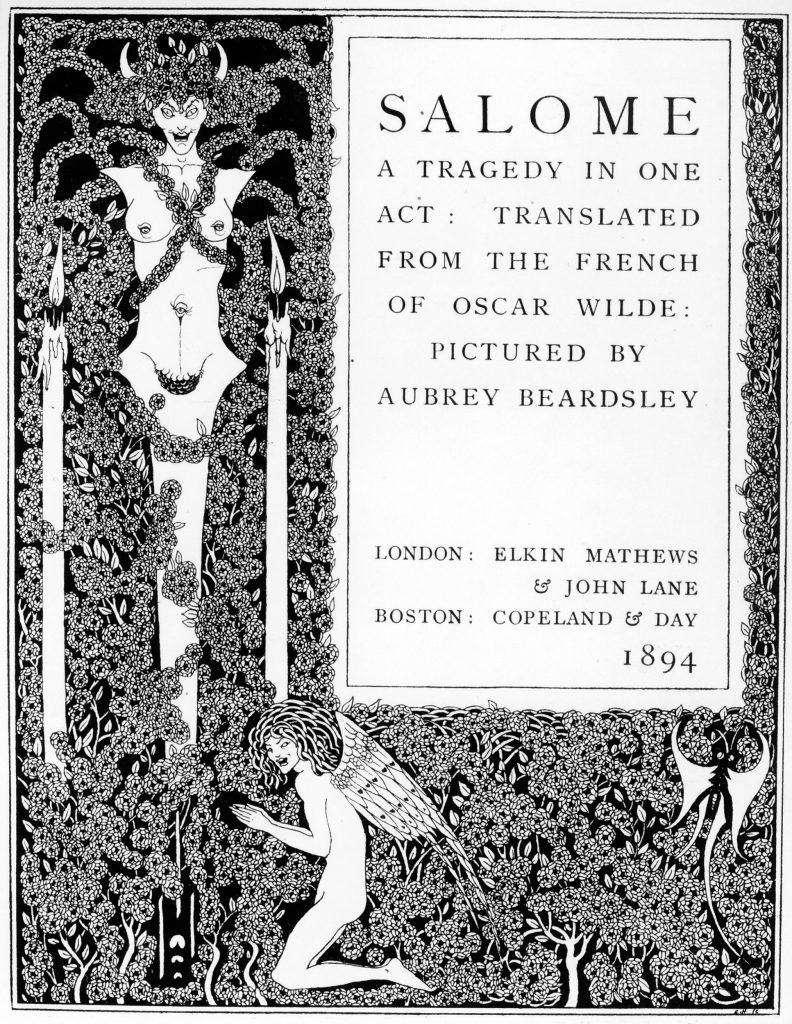

Aubrey Beardsley, Inside cover illustration for Oscar Wilde, Salome, 1894.

Wilde’s play was made all the more impactful by the work of British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898). Beardsley was a controversial artist. He is considered, alongside Wilde, as one of the leading figures of the Aestheticism movement and a precursor and forerunner of Art Nouveau. His black ink drawings are often dark, grotesque, and erotically charged.

In his illustrations for the English translation of Wilde’s play (which Wilde had originally written in French in 1893), Salome appears to exert a devilish and witch-like feminine power.

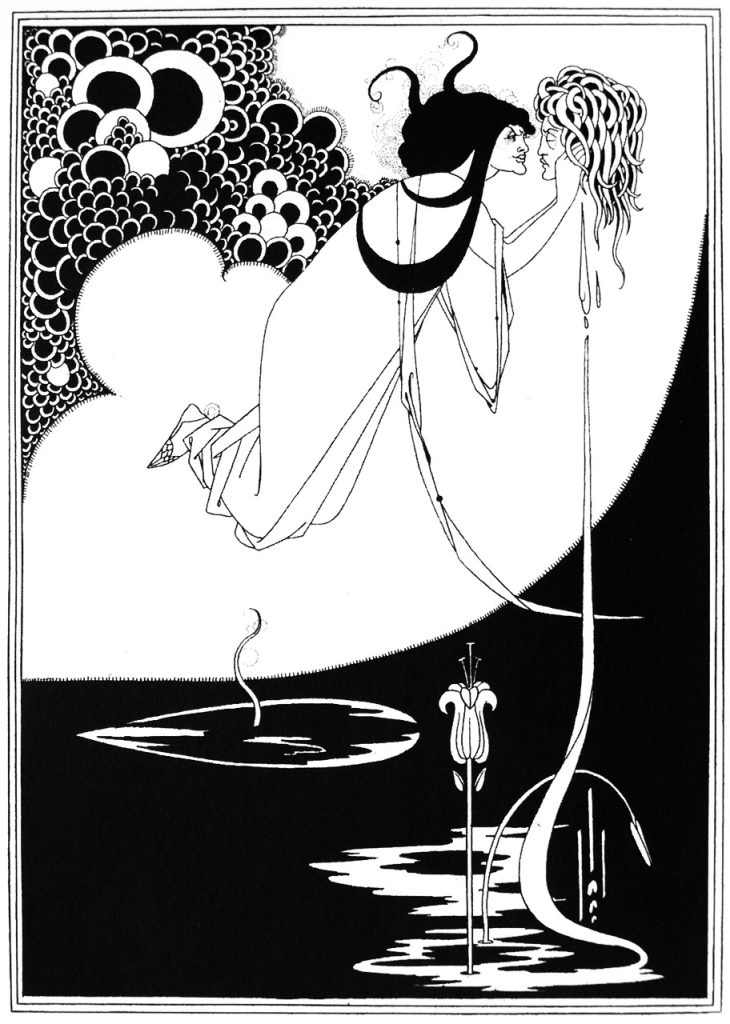

Aubrey Beardsley, The Climax, 1893.

Wilde’s play was the inspiration for Richard Strauss’s opera of the same name that debuted in 1903. This is where a new characterization of Salome took hold on a broader stage. Famously, Strauss (1864–1949) formalizes Salome’s dance for Herod as the so-called “Dance of the Seven Veils”—giving it a heavily eroticized spin and establishing the character of Salome as an erotic symbol in art from then onwards.

Ludwig Hohlwein, Poster for the Richard Strauss-Woche depicting Salome, 1910, Munich, Germany.

Since then, Salome has been mostly associated with sin, sexuality, and eroticism. Inspired by the 19th-century readaptation of the character, many prominent artists have left her role as a femme fatale unquestioned—unclad or scantily clad, her features have been wild and exoticized, and her body language overly sexualized. From then on, signs of her earlier image are very much absent.

In modern context, Salome seems ripe for overhaul again. As we look at the portrayal of women with a more critical eye, we see issues of colonialism, misogyny, and Orientalism. All these played a huge part in Salome’s portrayal in 19th-century art. However, both the clueless victim and the exotic temptress seem inappropriate and reductive when representing Salome the historical figure. Perhaps it’s finally time to look at the myth of Salome with a fresh perspective—and give her more credit than she has been given so far.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!