4 European Events Harmonizing Art, Nature, and Techno Music

Techno and electronic music have always shared an intimate relationship with art, intertwining rhythms, beats, and melodies with visual expressions...

Celia Leiva Otto 30 May 2024

A fanciful costume, a theatrical pose, the right light… and for a few seconds the viewer is immersed in a “living picture.” You have probably recently seen in social media some pieces of art recreated from homes. But do you know it is not only a 2020-pandemic challenge? This play has quite a long history.

In the last few weeks we all learned staying at home can be both really boring… and really creative. One of the most engaging challenges was started on an Instagram account Tussen Kunst & Quarantaine (Between Art and Quarantine) and promoted by the Rijksmuseum. The Dutch action soon inspired other museums around the world, like the J. Paul Getty Museum or the National Museum in Warsaw, to spread the trend.

Inspiring (and often hilarious) recreations of the paintings are now trending on social media… but this is definitely not a new play. Let’s see how it looked in the past, especially in Polish culture.

The history of this para-theatrical art form known as tableau vivant reaches back to the late 18th century. At first, it was a kind of salon game, an added attraction at a costume ball, or a way to stave off boredom on a winter’s night. They gained wider popularity, however, in the following century by appearing on theater stages (as spectacular play finales), being put on at parades and fairs, or appearing at patriotic gatherings and emboldening crowd’s spirits. All it took was an appropriate subject and a skilled arrangement.

Interestingly, recreations of existing paintings were not all that common. In the 19th century, the main source of inspiration was literature, with tableaux vivants serving to illustrate scenes from the likes of Quo Vadis, The Trilogy, or Pan Tadeusz. Also drawn from were momentous events in Polish history, Biblical stories, and mythology. Sometimes, these scenes portrayed abstract notions like war and peace or the four seasons.

Even when no painting was used as a template, the ideal composition was supposed to look “like a painting.” Because of this, the most highly-praised arrangements were designed by painters. After all, who better than an artist to compose groups of figures, select the colors, and see to the lighting? “Arranging these play-like pictures is the esteemed painter and trained archaeologist Aleksander Lesser,” informed the magazine Kłosy in 1871 in a piece on “living pictures”, which is based on a drama by Deotyma (Jadwiga Łuszczewska) and staged at Warsaw’s Teatr Wielki.

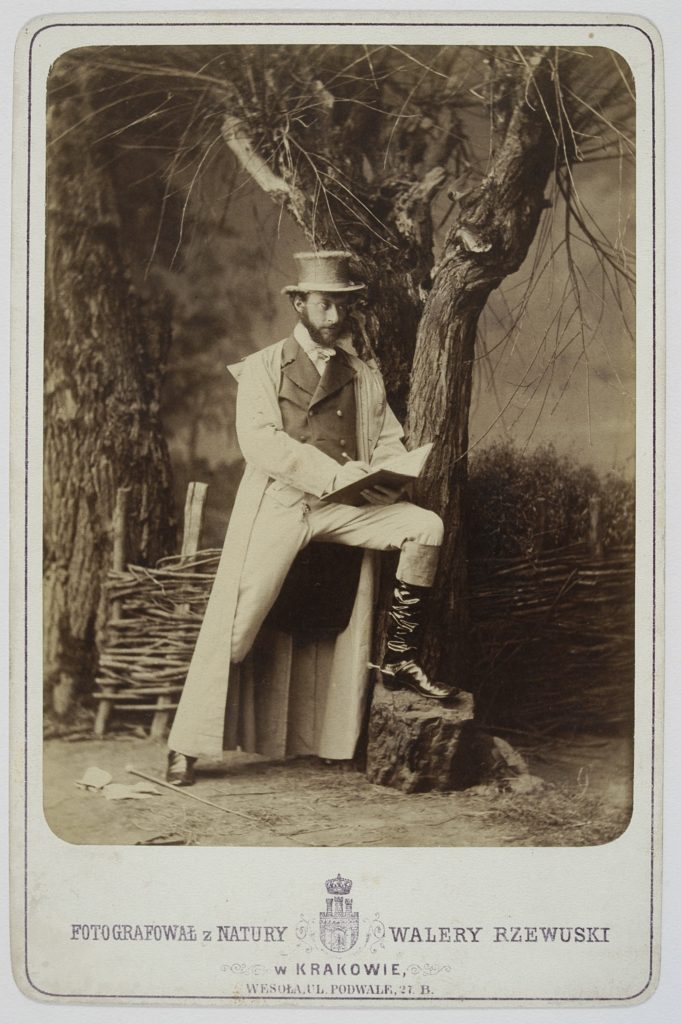

Often, many hours of preparation resulted in a show barely a few minutes in length. How could these fleeting moments be immortalized? The editorial board of Kłosy commissioned Lesser to produce six wood engravings “to commemorate the spectacle and to give the magazine’s remote readers a sense of what it was like.” Meanwhile, in 1884, Walery Rzewuski photographed a group of figures in costume as characters from Henryk Sienkiewicz’s With Fire and Sword. The photos documented the tableaux vivants shown at the Teatr Miejski in Krakow and were initiated by the pianist Marcelina Czartoryska. The novel’s cast of characters was enthusiastically portrayed by a group of aristocrat amateurs, with two young painters, Jacek Malczewski and Antoni Piotrowski, supervising the composition.

The performers taking part in a tableau vivant would freeze, motionless and silent, and the audience could add to it. Published in an 1884 edition of Kłosy was the poem Posłannictwo muzyki by Deotyma with an annotation reading: “… poem recited during a presentation of tableaux vivants at the Music Society on St Cecilia’s Day and 6 December.” The same issue also contained an illustration depicting the scenes. The caption below provided information on the composition’s creators (among them was the painter Wojciech Gerson) and on the type of music accompanying the event (e.g. “dance” music or “battle” music).

Tableaux vivants were also put on at family gatherings. In the pages of Wędrowiec, Janusz Korczak wrote in 1900:

“These long winter evenings. How can we make them more enjoyable for our children and youngsters? There are amateur theatres, tableaux vivants, improvised concerts, board games, recitations, discussions, group reading, a bit of dancing. […] All it takes is to choose something suitable, round up a jolly group and the fun starts.”

Janusz Korczak

He recommended “tableaux vivants with general themes like the four seasons” as well as more educational ones on “historical or geographic subjects.”

Scenes from Polish history were staged during patriotic festivities, both while Poland was under foreign partitions and during the interwar period. For instance, in 1920, the anniversary of the January Uprising was commemorated in Vilnius with “a range of speeches, choral and solo concerts, and, to cap it off, tableaux vivants illustrating the era of the January Uprising, composed on the basis of paintings by the renowned Polish painter Artur Grottger,” as informed the magazine Pod Karabinem and published by the Vilnius branch of the Voluntary Legion of Women.

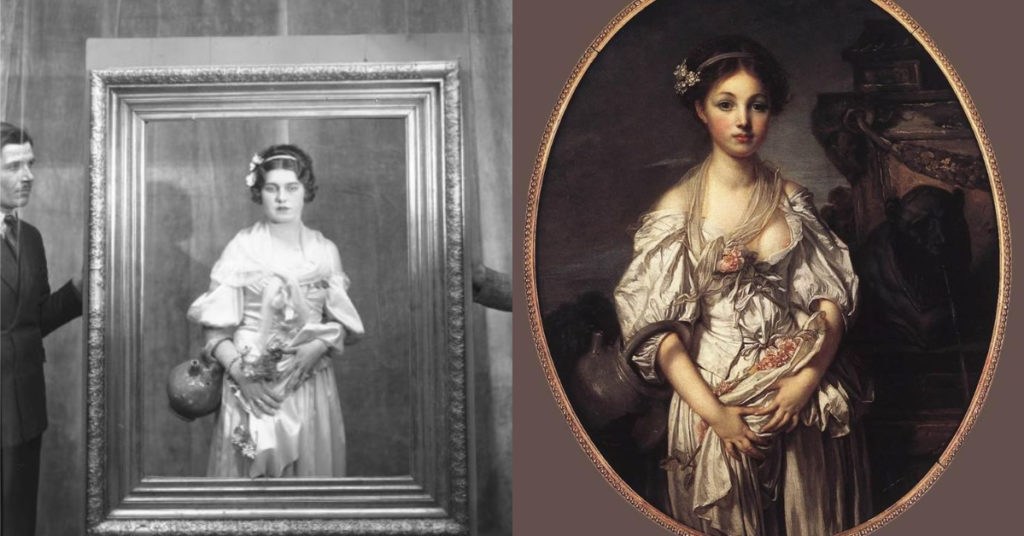

Thematic tableaux vivants also appeared during charity drives. The Nowy Dziennik Daily reported in May 1932 that the Youth Aid Society was organizing a “Grand Evening of Tableaux Vivants. The most famous canvases from Europe’s museums will be reproduced by the fair ladies of our city. Shown will be works by masters like Velázquez, Van Dyck, Vigée Le Brun […] and many others.” Taking on the roles of the paintings’ heroines were actresses from an amateur theater in Krakow. Photographs preserved in the National Digital Archive show the professionalism of the costume design; but, as Maria Gerson-Dąbrowska advised in a brief manual titled Obrazy żywe [Living pictures] from 1920, costumes can be made from “bed linens, throws, curtains, shawls, muslin, or fur. All that’s needed is some creativity and a skilled hand.”

This article was published on the educational website Historia Poszukaj maintained by the National Institution for Museums and Public Collections.

Author’s bio:

Karolina Dzimira-Zarzycka – art historian and Polish philologist. Author of popular science articles about Polish culture and women’s history, published in online magazines and journals, as Historia:poszukaj, Culture.pl and Szajn. Instagram: @karolinadzimirazarzycka.

Author: Karolina Dzimira-Zarzycka, Translation: Simon Wloch

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!