Simon Hantaï was a Franco-Hungarian painter whose work is marked by a reflection on painting techniques. In an evolution that carried his art to abstraction he crossed path with several art movements (Surrealism in particular), techniques, and materials.

Hantaï’s artwork started in Hungary, his native country, where he was a student in Budapest at the School of Fine Arts.

This first period is the only figurative one in his work. We can see the artist’s search for his style through these paintings, drawings, and water colors. As a student he discovered many artists through his courses, Matisse and Bonnard‘s work in particular had a great influence on Hantaï’s art and the role of colors in it. We will see that this reflection on color will lead him to abstraction.

This oil painting is imbued with the influence of Matisse and Bonnard. First of all its title refers to the 1906 painting The Joy of Life by Matisse. Next the style and the colors echo his desire to break with realistic representations. The colors are characteristic of Fauvism and Les Nabis. Here color is the main subject of the painting, it is vigorous and alive. The short brush strokes, similar to those of Matisse and Bonnard, convey the idea of movement.

Later his attraction to French artists took him to France where he moved with his wife in 1948. She was the Hungarian painter Zsuzsa Biro.

Paris: the Center of Surrealism

Hantaï arrived in Paris in 1948 where he discovered its many museums and galleries. There he was immersed in French artistic culture. In post war France he met cubist, futurist, dadaist and surrealist artists. Under the influence of great artists such as Ernst, Dubuffet and Picasso he explored different mediums and techniques such as collage, frottage, grattage with razor blades, paint-run and even folding.

The following piece is an example of his work in collage. Here he associates painting with collage of painted papers. We can see discrepancies between the two brown sheets and between the glued part and the blue painted part. This underlines the difference between the two techniques, the evolution of his work, and the reflection around artistic material.

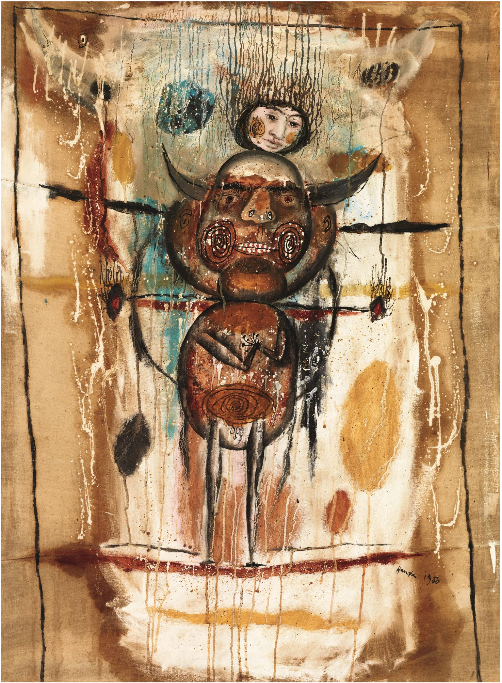

This piece from 1950 reflects this exploration. We can see the use of paint-run and different ways of working with it. It can go from top to bottom or from bottom to top, sometimes it is thrown, sometimes it is dropped. This painting sets itself between figuration and abstraction, it announces Hantaï’s interest in surrealism.

Simon Hantaï and the Surrealists

Surrealism in a Few Words

In 1924 the French poet Andre Breton first defined what the Surrealism was in his Surrealist Manifesto. He described surrealism as the expression of the mind uncontrolled by reason and expectations of society. The artists express themselves in all mediums (painting, sculpture, poetry, dance, etc).

If you want to discover the work of two major surrealist artists check out these articles on Max Ernst and Joan Miró.

A Turning Point

In 1952, Simon Hantaï anonymously dropped off one of his paintings on André Breton’s porch. It may sound strange but at the time it was a common practice to get the attention of well-known artists.

It turned out that Breton liked the piece so much that he displayed it in a gallery. Hantaï thus introduced himself and joined the Surrealist group. In 1953, Breton organized his first solo exhibition.

This piece combines several elements such as collage of printed illustrations, feathers, and bones. The elements all together reflect Hantaï’s exploration of artistic possibilities. Such possibilities are greater in Surrealism. Indeed, the movement encouraged the use of diverse materials. The Surrealistic influence is also visible in the exploitation of a Surrealist bestiary.

However, Hantaï separated from the Surrealists, the movement had evolved and Hantaï wanted to go back to its fundamentals: an inner painting, freed by automatism.

We can see his use of automatism in A pale Flame, Barely Visible. The geometric patterns are repeated and are not narrative.

Separating with the Surrealists later lead him to new reflections about art and a desire to further explore abstraction.

The Gestuelle Period

Hantaï invented a new way of painting: he painted his canvases with vivid, strong colors, he then covered it with a greasy, darker color such as black or brown. Finally, he scraped the greasy layer with several tools (razors, metallic pieces of his alarm) to expose the vivid color below.

We can see the influence of Jackson Pollock and Abstract Expressionism in the strong and energetic gesture given here by the removal of material and also in the space that the notion of accident occupies.

However, Hantaï was not completely satisfied with this technique and continued his research.

Scriptural Period

This period is synonymous with Hantaï’s constant research and experience. At this point he completely questioned his work and techniques. His gestures are no longer big and violent, they evolved into microscopic ones. The multiplication of these tiny inscriptions contrasts with the size of the canvas, which emphasizes the meticulousness of this gesture.

In this work focused on writing he continues in his evolution into abstraction. Here he plays with different points of view. We see the artwork differently depending on how close we stand to it. The vision is thus distorted.

This period is best represented in two paintings:

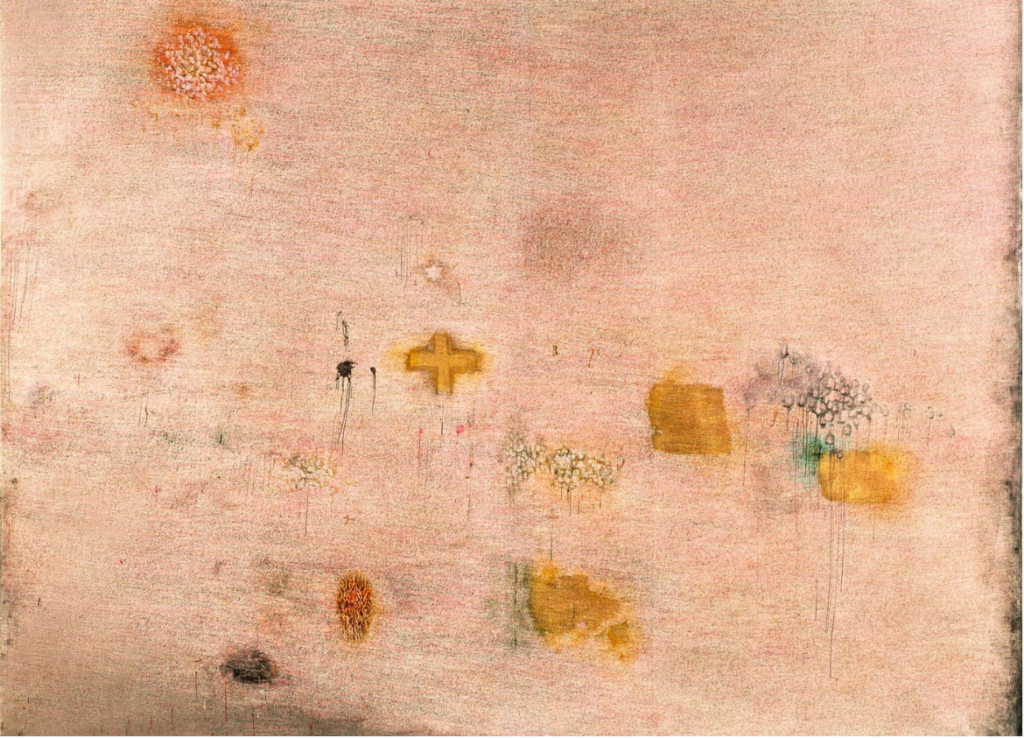

The Pink Writing

Pink Writing was made in 365 days. Each day of the year, the artist wrote sentences extracted from the Missal, a liturgical book for the Roman Catholic, and also from books on philosophy and mysticism. It is interesting to see that Hantaï only used red, green, purple, and black China ink. Even though no pink was used in the process the layering of these colors resulted a pink effect. The addition of the colors in our eyes makes it look pink, this is an illusion.

Since the words are signs that refer to Hantaï’s readings, the painting is a field with other signs that demarcate the space on the canvas: a Greek Cross and a Star of David.

The painting is thus a part of a ritual. The process is repetitive and asserts Hantaï’s position in favor of automatism. He builds his scriptural work on this automatism.

To Galla Placidia

Hantaï dedicated this painting to the Roman empress Gallia Placidia but above all it was a reference to her mausoleum in Ravenna (Italy). The artist found inspiration in the mosaics of the mausoleum. Its brownish colors are due to the addition of several different colors, similar to the painting. In Hantaï’s work it results from a multitude of lines whose contrasts offer effects of light and movement. We can see a cross in the light effects, which echoes the mausoleum: it’s part of the first Christian mosaic.

This scriptural period therefore was a turning point in Hantaï’s work. It sits between a complete questioning of his previous work and the result of it in his following and final period.

Folding Technique

The folding technique did not appear for the first time in this period. Hantaï already experimented with it but here it becomes systematic.

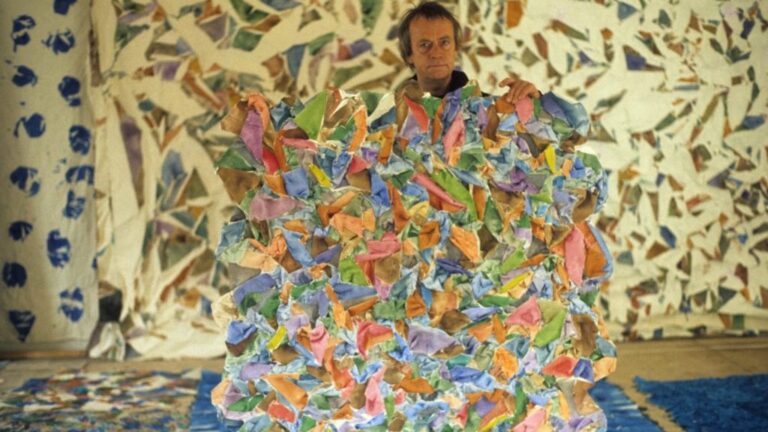

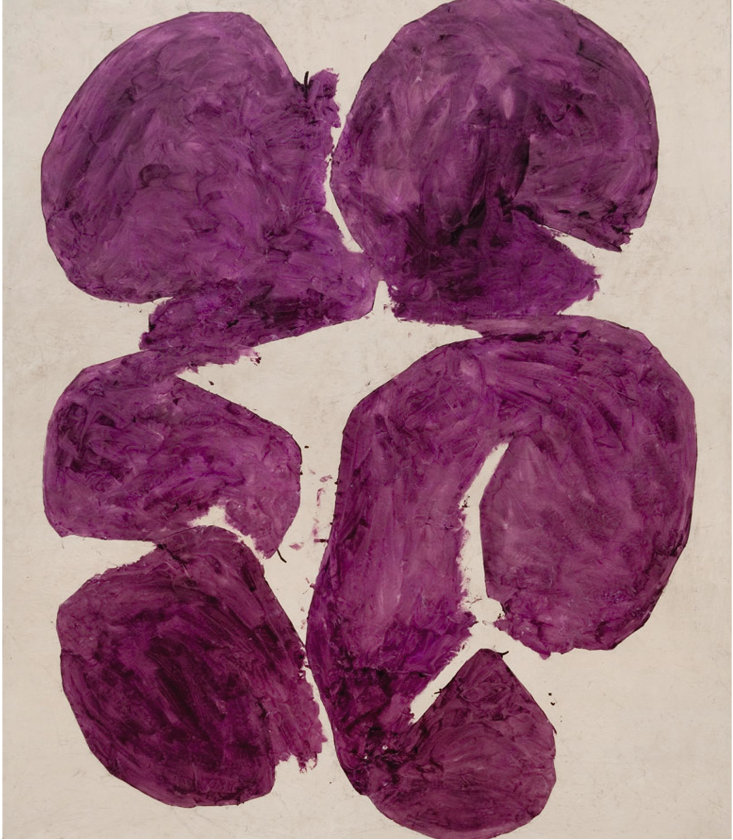

It consists of folding a large canvas and painting on the exposed areas. Once the canvas is unfolded, the colors turn into discontinuous and unpredictable forms. Contrast appears between the painted parts and those hidden in the process. This contrast gives birth to both abstract and poetic forms.

In this technique Hantaï expressed questioning about the artistic gesture, he wanted to make art without using any specific talent.

“How to make the exceptional banal? How to get exceptionally banal? Folding was a way to resolve this issue. Folding did not proceed from anything. It was only necessary to put yourself in the state of those who have not seen anything yet, to put yourself in the painting. We could fill the folded canvas without knowing where were the edges. Therefore we don’t know where it stops. We even could go further and paint with closed eyes.”

Catalog of Simon Hantaï’s donation to Paris’ Modern Art Museum, 1998

In this catalog, Hantaï described his process for each series of paintings. We can see an evolution in his treatment of colors, the color white in particular.

An Exploration of Color

His series named Meun, after the village Hantaï lived in, is a reflection on color and light; how they respond to each other, how they influence each other.

At first sight, the Meun paintings are monochromes. Hantaï discovered that in a certain light, the addition of the white unpainted part of the canvas and the painted one reveal a new color. This mysterious and unexpected color can be compared to the appearance of the pink in the previous painting Pink Writing. White thus becomes a central element in Hantaï’s work.

White conveys a form of dynamism in the painting. Therefore, the painted and unpainted parts are equally important. The presence of the white is more and more accentuated, it almost takes over the painting that supports it.

“Folding is made in a way that restricted colored areas, activates the white, and reveals the multiplicity of its values.”

Catalog of Simon Hantaï’s donation to Paris’ Modern Art Museum , 1998

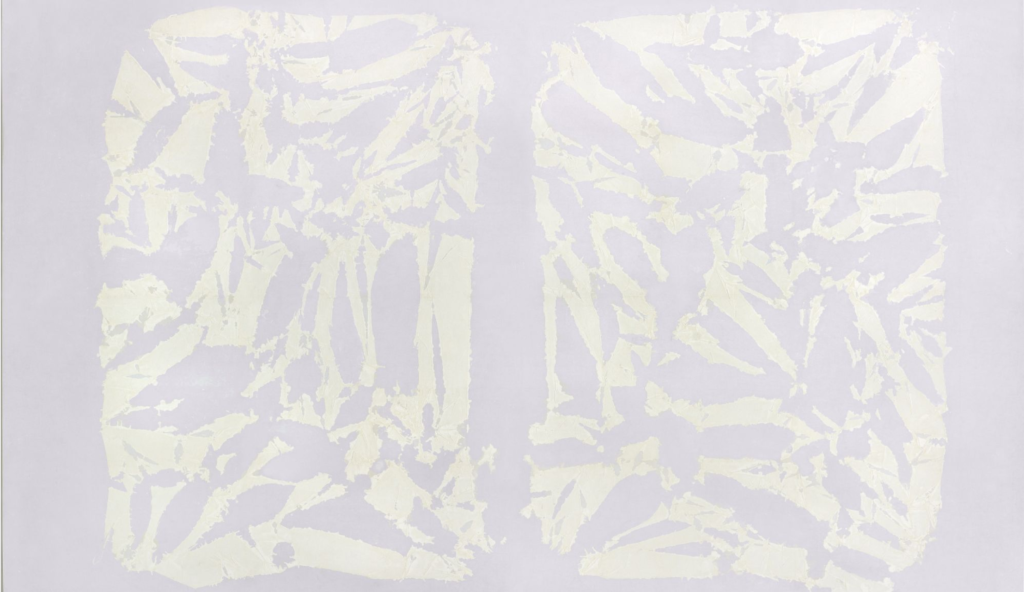

The artist completes his reflection on the interaction with the white in his last series: The Tabulas.

In 1982, the exhibition Tabulas Lilas displayed five paintings of white paint on flax canvas. In the light, from the contrast between two tones of white emerges a third color: lilac.

The End of the Journey

Hantaï had reached the climax of his career and at this point he decided to retire. For fifteen years he refused to take part in any exhibitions or other public events. Nevertheless, he did not stop working. He then accumulated all his new paintings in his Paris flat. In 1997, he began to take part in exhibitions again and gave many of his paintings to the city of Paris and the Pompidou Center. He passed away in 2008, after years of artistic research, leaving a rich legacy for generations of amateur artists to come.

You can explore Simon Hantaï’s work in his archives.