Eugène Delacroix in 10 Paintings: Poetry, Passion, and Power

Early 19th-century French art was a battle between cool, crisp, precisely observed Neoclassicism and Romanticism’s passion for emotion, drama,...

Catriona Miller 3 July 2024

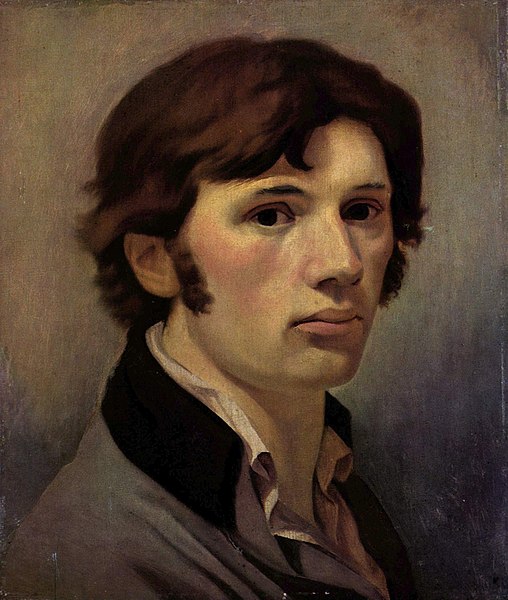

Philipp Otto Runge died of consumption at the same age as Christ, which to those who believe in signs might be crucial since Runge was a mystic who claimed to “see through the mysteries of God” and provided Brothers Grimm with a horrifying tale. Art critic Robert Hughes described him as “the closest equivalent to William Blake that Germany produced.”

Because he was a sickly child, Philipp Otto Runge often needed to stay home and his mother had to keep him busy. Therefore, she taught him scissor-cuts, an art which stayed with him all his life. His older brother Daniel supported his artistic talent by financially aiding Philipp when he went to Copenhagen and later to Dresden, where he met Caspar David Friedrich. Unfortunately, there are very few surviving paintings of Runge from this time. This is due to the great fire which overtook the Glass Palace of Munich in 1931, which destroyed most of them.

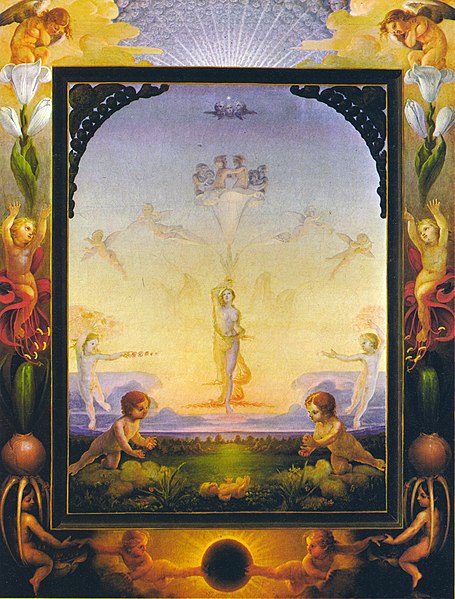

Like many Romantic painters, Runge was into a concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. This was meant to be the ultimate masterpiece, as it fused painting, sculpture, architecture, and sometimes even music and literature. Runge therefore intended to exhibit his work in a specially designated building. He planned a series to contain four paintings, representing times of the day. These were meant to be viewed with a music and literary accompaniment. Runge began with large-scale engravings of the works, which turned out to be successful. However, apart from the two versions of the painting you see above, he never painted other parts.

Although, the great writer and poet J.W. Goethe did not appreciate Runge’s Romantic painting, he definitely saw potential in his scientific writing (by the way, the two were good friends since their first accidental meeting in Weimar in 1803).

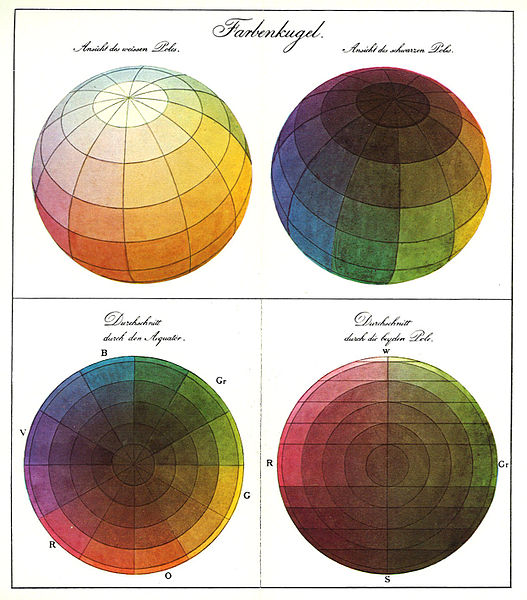

In fact, the treatise on colors Farben-Kugel (Color Sphere) that Runge managed to publish in Hamburg just few months before his death, was appreciated by both his contemporaries and a later generation of artists and art theoreticians, represented by Franz Marc, August Macke, and Paul Klee. The latter described the essay as the “teaching essential for the painting yet to come.”

In the 1812 edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, one tale bears an annotation that it had been provided by Philipp Otto Runge. It’s one of the most terrible and frightening ones, dealing with murder, child abuse, and cannibalism (!). I’m not going to tell you the plot, but what is important to emphasize is the centrality of the titular juniper tree around which all characters’ actions revolve.

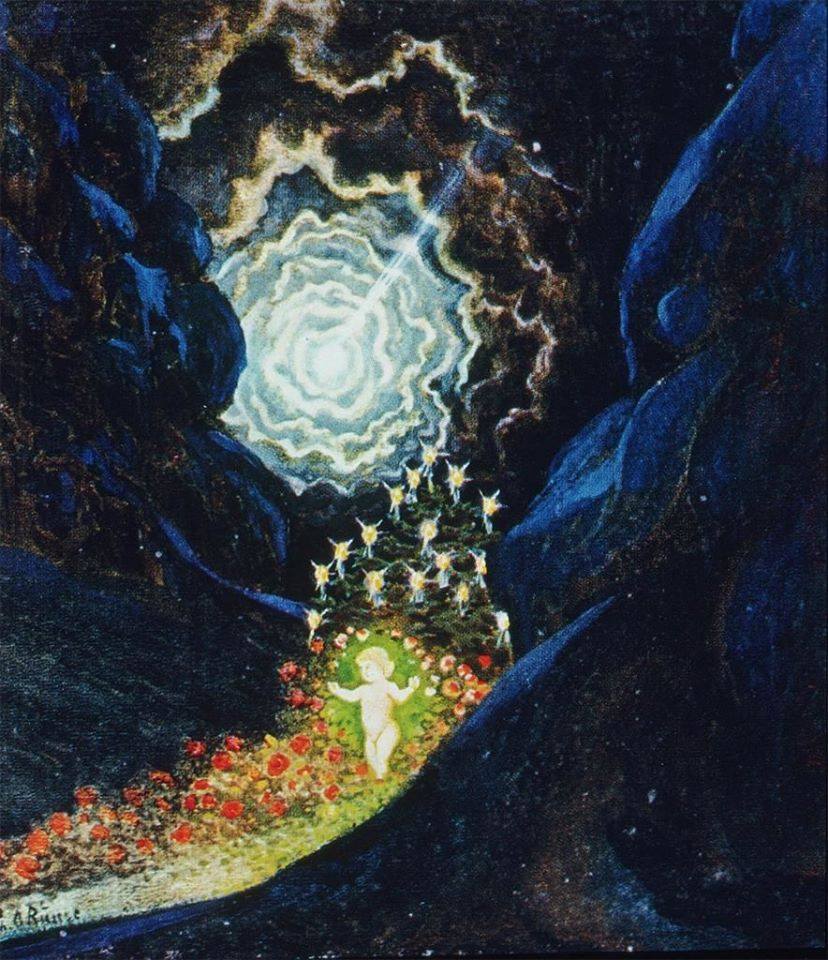

For Runge, inspired by the writings of a German Christian mystic Jakob Böhme, the tree symbolized the cosmic harmony between the spheres of the Sky, the Earth, and the Men. “The spirit is found in trees,” he wrote. While searching for harmony, Runge found it in the unity of colors, forms, and numbers. Blue, yellow, and red were to symbolize the Trinity: blue stood for God the Father and the night, red for morning, evening, and Jesus Christ, while yellow represented the Holy Spirit.

Runge was a Christian mystic who deeply believed that science was imbued with symbolism, in which mathematics holds hands with Kabbalah, chemistry with alchemy and physics with occultism. He once wrote that:

Science has reached the clarity of opinion. Yet the thoughts and experiences stretch their wings towards a country of nostalgia way further than Japan.

Author’s translation of the quote found in Il pittore che scriveva le fiabe dei fratelli Grimm, StileArte – Quotidiano di Cultura Online.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!