Masterpiece Story: The Setting of the Sun by François Boucher

With sweet putti, handsome gods, beautiful nymphs, vibrant colors, and elaborate compositions, The Setting of the Sun is a testimony to François...

James W Singer 8 February 2026

As Europe burned during WWII, Wassily Kandinsky, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1933, lived as a recluse in his Neuilly-sur-Seine apartment. In that confined world, painting became a shelter, a kind of oasis of brightness and optimism. In times of war, as if seeking refuge in nature, Kandinsky populated his abstraction with a multitude of cellular forms and small, fantastical creatures. One of such works is his fascinating Sky Blue.

Born in Moscow in 1866, Wassily Kandinsky didn’t begin formal art training until relatively late. He studied law and economics at the University of Moscow only to abandon that career at 30 and move to Munich in 1896 to study painting at the Academy of Fine Arts. In Munich, and through years of travel and immersion in Europe’s most experimental circles, Kandinsky grew increasingly dissatisfied with art as mere representation.

Around 1910, his work tipped decisively toward non-objective abstraction, and in 1911, he co-founded Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) with Franz Marc and others, pushing a more expressive, “spiritual” language of color and form

Wassily Kandinsky, Landscape with Factory Chimney, 1910, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

The First World War forced him to leave Germany in 1914 and return to Moscow, where contact with the Russian avant-garde sharpened his geometric language. In the 1920s, that impulse crystallized at the Bauhaus, where he taught from 1922. Geometry moved to center stage: circles, arcs, angles, and the dialogue between straight and curved lines, visible in works such as Yellow-Red-Blue (1925), where strict organization coexists with vibrant chromatic life.

Wassily Kandinsky, Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

When Nazi pressure led to the Bauhaus’s closure, Kandinsky left Germany in 1933 and settled near Paris. In the relative seclusion of those final years, the cool rigour of Bauhaus geometry gradually softened into a lighter, more playful vocabulary, setting the stage for the floating micro-world of Sky Blue.

Despite the growing hardships of war, Kandinsky refused to emigrate to the United States and spent his final years in France, settling with his wife in Neuilly-sur-Seine in December 1933. He turned their apartment into a makeshift studio, working by the bay windows overlooking the Seine and the distant outline of Fort Mont-Valérien—light, he later noted, that subtly expanded his palette.

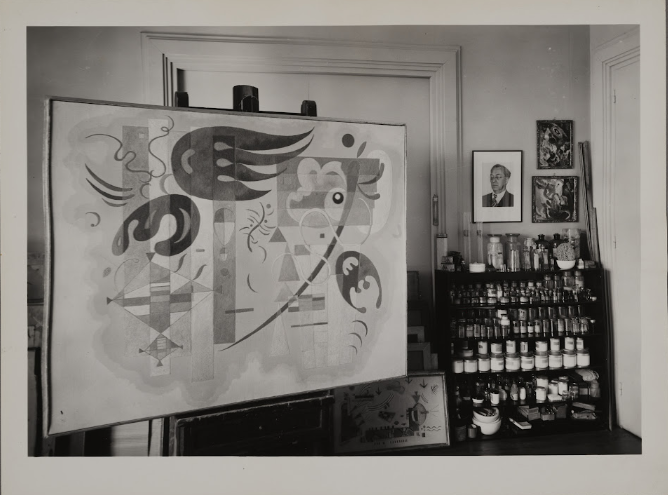

Wassily Kandinsky’s studio in Neuilly-sur-Seine when he died, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

Paris placed him within a dense artistic network, from Léger and the Delaunays to Mondrian and Breton. However, he relied mostly on a smaller circle of close friends such as Jean Arp and his wife Sophie Taeuber-Art, Alberto Magnelli, and Joan Miró. Still, recognition was hard to secure. In a scene shaped by Cubism, Surrealism, and above all Picasso, Kandinsky largely remained on the margins, determined to preserve his own voice.

Wassily Kandinsky, The Little Red Circle (Le petit rond rouge), 1944, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Detail.

It was a remarkably productive period. He produced around 144 paintings and more than 200 watercolors and gouaches, although he sold very little. Many of these works were acquired by Solomon R. Guggenheim, one of his most enthusiastic supporters. After the summer of 1942, shortages in occupied France forced him to use improvised supports such as wood or cardboard. His palette darkened, and his compositions became more detailed and structurally complex.

Artistically, those years brought renewal. The cool rigor of Kandinsky’s Bauhaus geometry softened into a more organic, nature-inflected abstraction, filled with buoyant forms and a brighter palette that blended pastel tones with sharper, acidic accents. Sky Blue belongs to this late period—and you can feel the shift at once. The outlines loosen, the shapes stop behaving like strict geometry, and the whole image seems to float. Against a blue ground, biomorphic forms—soft-edged, brightly colored—drift like tiny living creatures suspended in a sky-blue sea.

Wassily Kandinsky, Sky Blue (Bleu de ciel), 1940, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France.

The title suggests it may be a mistake to get too distracted by the tiny biomorphic figures, and that the real focus should be on the background. Blue was Kandinsky’s favorite color, and in his writings, he links it to the sky and to a pull toward the infinite. Here, the ground takes on a nuanced blue tone, seemingly neutral, but undoubtedly suggestive: it is not a flat background, but a kind of air, the sky blue that he could glimpse from the window of his studio towards Fort Mont-Valérien.

Wassily Kandinsky, Sky Blue (Bleu de ciel), 1940, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Detail.

Traditionally, backgrounds tend to be softer than the foreground, so that the viewer’s gaze is focused on the “main element.” In Sky Blue, Kandinsky breaks with this hierarchy. The background is as intense as the shapes themselves, if not more. Why do that? Because Kandinsky is not primarily trying to describe a scene, but to tune in to the viewer. The blue field becomes the psychological setting of the painting, the element that strikes you first and most continuously, while the floating forms act less as subjects to be interpreted than as sensations to be accompanied.

In other words, the key question is not simply “what are these shapes?” but “what does this blue mean to me?” In Kandinsky’s own words, the more expressive the work, the less it is subject to a single, stable meaning, and that opening, that invitation to keep asking questions and feeling, is precisely where its spiritual power begins.

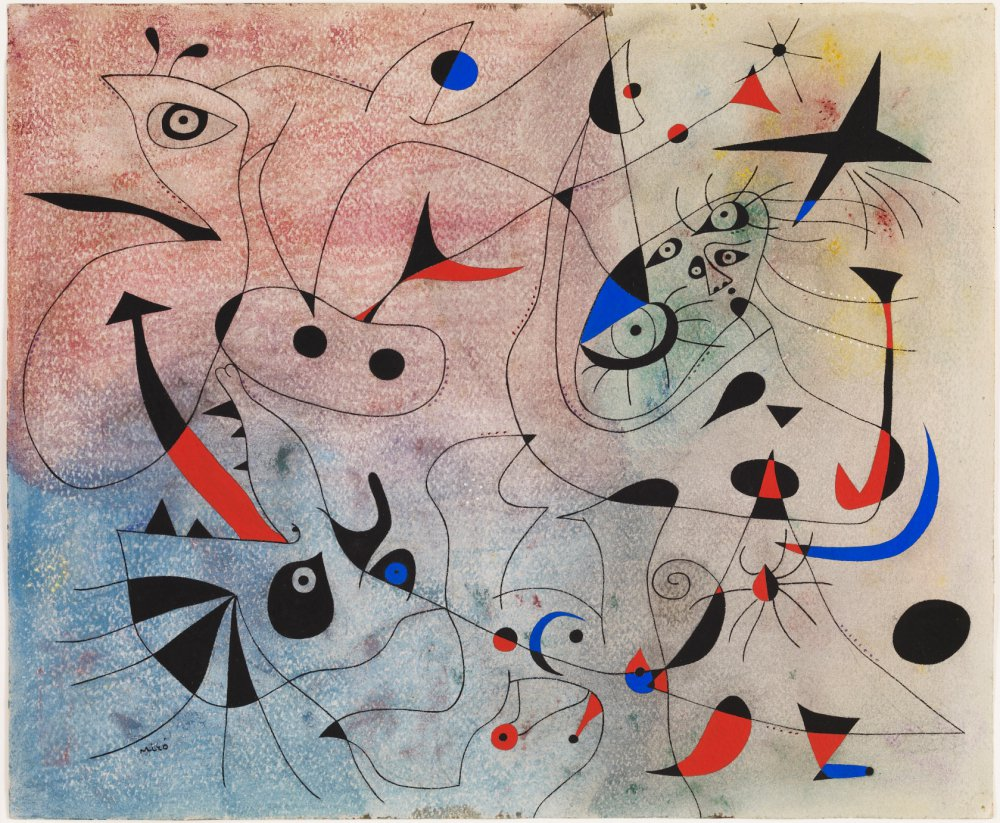

Even if Kandinsky wants the background to take centre stage, it’s hard not to linger on the peculiar figures that animate the space. In Paris, he absorbed the biomorphic vocabulary encircling him—shapes associated with artists such as Jean Arp, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, and Joan Miró—while developing a language that is unmistakably his own. Some critics have noted affinities with Miró’s Constellations: the sense of organic drift, the playful scale, and the bright insistence of primary colors.

Joan Miró, Morning star (L’Etoile matinale), 1940, Fundación Joan Miró, Barcelona, Spain.

The tiny, imaginary beings—half-animal, half-fantastic—also recall the vivid pattern designs Kandinsky produced in the early 1940s for decorative textiles made for the Société industrielle de La Lys, where stylized forms scatter across the surface like motifs in motion. This lightness of touch and chromatic sparkle has led some critics to describe Sky Blue as a “chinoiserie”—a label meant less as imitation than as a shorthand for its ornamental rhythm and color sensibility, sometimes associated with East Asian art.

In Sky Blue, Kandinsky shows how abstraction can be both rigorous and deeply humane. What first reads as a simple field of color becomes a psychological space—an atmosphere that holds the viewer—while the tiny biomorphic figures add rhythm, play, and a sense of fragile life. Painted in the shadow of war, the work doesn’t deny darkness so much as propose another register: a shelter made of color, where looking becomes a quieter form of resilience. In the end, Sky Blue invites us to stop asking only what we see, and to notice what we feel as the painting slowly “tunes” our attention.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!