Allegorical “Millefleurs” Tapestry with Animals

Medieval tapestries commonly gathered real and mythical animals such as the deer and the unicorn, a quintessential medieval symbol.

In this symmetric composition, the birds form a circle around the tree at the top of the composition. As for the mammals below, they create another one around the unicorn and between the three trees. It is as if this assembly is joyfully dancing in a flower field. Yet, this tapestry is an allegory: all the elements represented are Christian symbols. Only the millefleurs background — French for thousand flowers — doesn’t have a religious meaning.

The person who commissioned the tapestry was definitely wealthy. A bit similar to photographic resolution nowadays, the more detailed a tapestry, the more expensive it would be.

As the title suggests, Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) painted a stag in all his majesty. The fog between the animal and the misty mountains behind him indicate the stag has climbed to the highest peak. The mountains in the background are high, but not as high as the royal antlers crowning the animal. The head proudly raised, the stag is looking upon his kingdom.

If this picture reminds you of something it is because it has been used ad nauseam in British marketing. Nonetheless, it is still considered a natural treasure. It must be said that this artwork contains a lot of meanings in so few elements. More than a heightened idealization of nature, the stag encompasses key values of the Victorian era such as heroism, pride, and elegance.

Founding member of the Expressionist art movement Der Blaue Reiter, Franz Marc (1880-1916) liked to paint animals. For the artist, who envisioned a spiritual quality to his art, their incorruptible nature was a means for this goal.

In this painting, one can recognize a tiger from behind. In fact, it is the only element that the viewer is able to clearly identify. As if he heard a sudden noise from behind, the tiger turns excessively to the left, almost creating a circle with his body.

Dramatically dynamic, the image is made of multidirectional applications of colors colliding with one another. Enhanced with angular black outlines, it creates an intense visual effect. Even the colors, bold and subjective, are exaggerated. According to Marc’s symbolic significance of the colors, the red surface surrounding the tiger — even merging with the tail — could signify that the predator is about to attack.

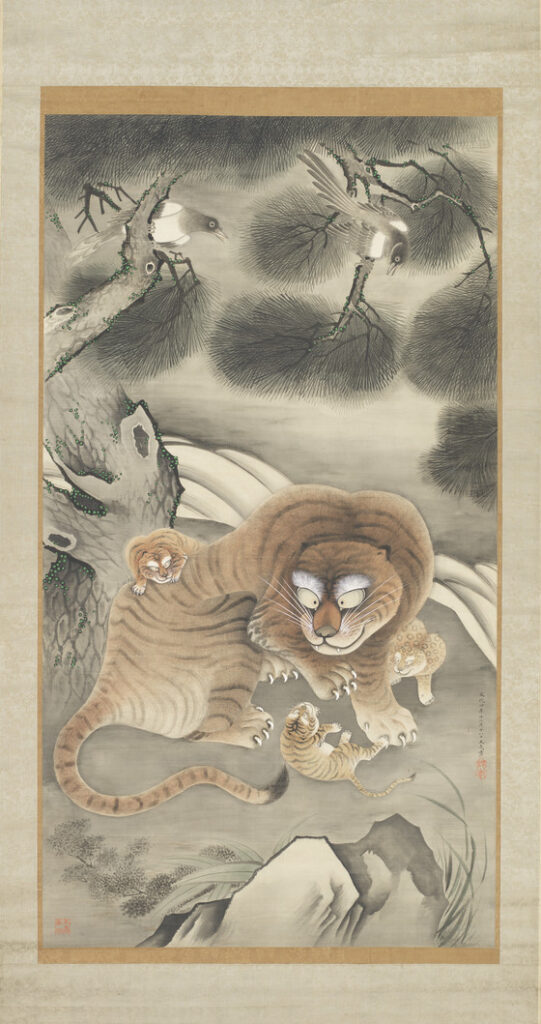

On the contrary, the tigers of artist Tani Bunchō (1763-1841) have no ferocity. We can even perceive a large smile on the adult, who tenderly looks at his progeny. The pair of magpies sitting on a branch above, a symbol of happiness in Asian culture, accentuate the harmony.

Tani Bunchō was an artist from the 18th-19th century who took part in the bunjinga trend — or so called Nanga school, an art mixing Chinese motifs and Japanese aesthetics. For example, we know the adult tiger in Bunchō’s scroll is a male because it has stripes. There aren’t any tigers in Japan and at that time it was thought that the leopard was a female tiger. Therefore males were represented with stripes and females with leopard spots.

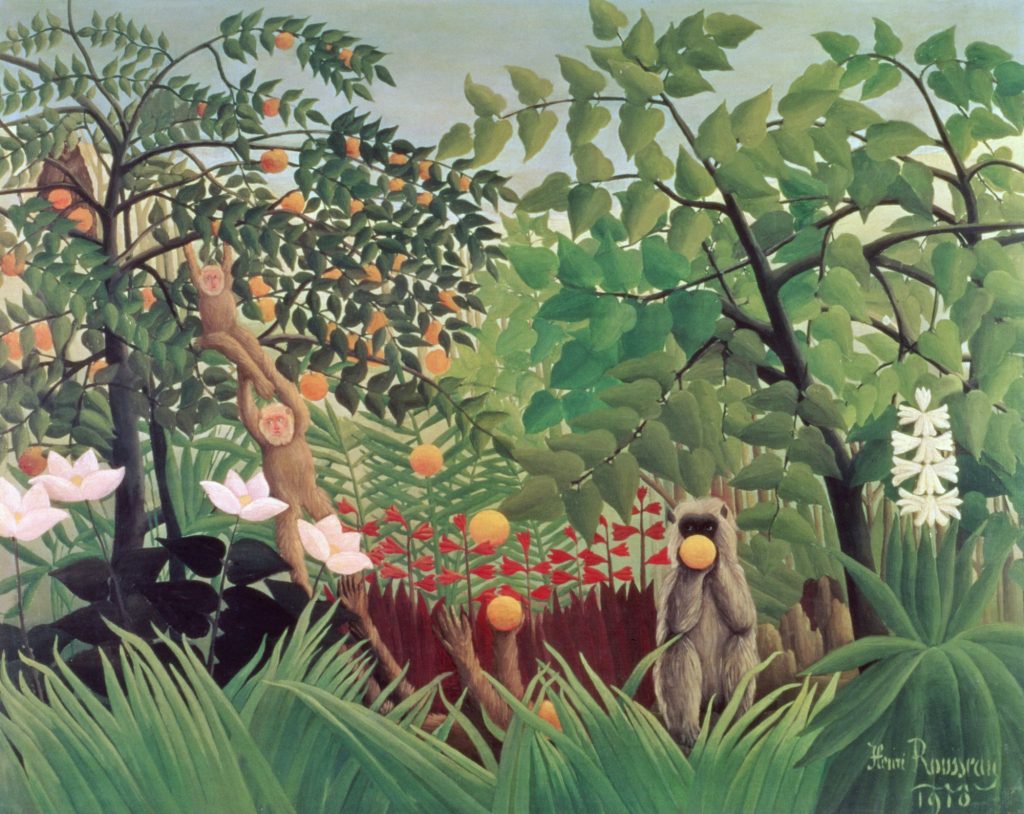

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) was a self-taught artist whose work is often characterized as both naive and primitive. Oddly enough, little has been said about the fierce tension often present in his work. Indeed, Henri Rousseau’s jungle is often the setting for hunting or fighting scenes, whether it is humankind versus animals or animals against one another.

In this specific painting a detail disturbs the apparent playfulness of the scene. Right in the middle bottom, one can see the arms of a monkey. The rest of the body hidden behind the high herbage, it would seem that the animal just fell down from his comrades hanging on tree branches above. To make things worse, heavy oranges are falling on the poor lad. This picture, hidden in the bigger narrative, definitely questions and contrasts the apparently idyllic scene.

The Kongouro from New Holland

George Stubbs (1724-1806) was a British painter from the 18th century, renowned for portraying animals in a scientific exactitude from live observations. Yet The Kongouro from New Holland is an exception in his career. The naturalist Joseph Banks, who visited Australia as part of Captain Cook’s first expedition, commissioned the artist to paint the animal from an inflated skin and some drawings.

For someone who actually never encountered a kangaroo in person, Stubbs managed to provide the overall character of the marsupial: big feet, long tail, small arms and alert attitude. Although the painting is considered a national treasure, I thought something was odd about this kangaroo. After comparing it with pages of photographs, I realized that the legs are anatomically incorrect.

This subtle error would not have been known in 1772 though. Indeed, if the kangaroo is now a popular Australian symbol, this painting was its first depiction in Europe.

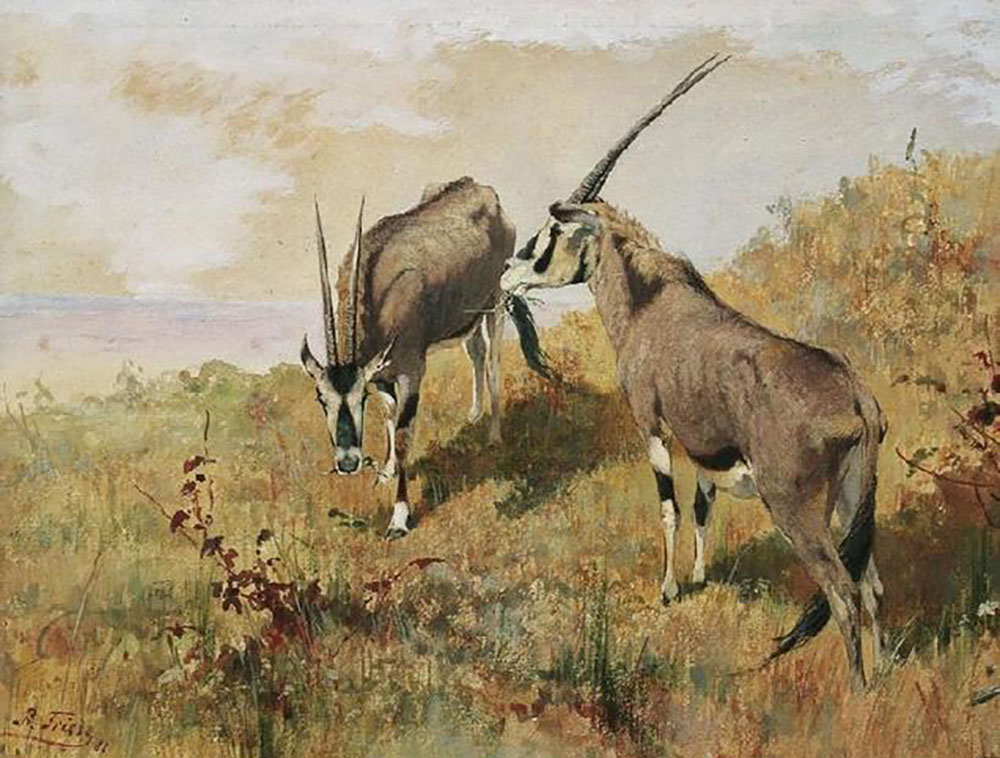

Zwei Antilopen (Two Antelopes)

German artist Richard Friese (1854-1918) was often on the move, from Eastern countries to polar regions. Therefore, Friese knew not only animals from different countries but he also had knowledge of their natural habitats.

The artist gave as much importance to portraying animals as to paint landscapes. In this painting, a couple of antelopes peacefully graze on top of a hill . Despite the thick application of the brush, the artist gave particular attention to details, such as variations in the tones of the animals’ coats. While one is focused on the ground the other is looking at the horizon, toward a large area of water.

One can almost feel the fresh air sweeping through the land, perceptible by the slight inclinations of the vegetation as well as the mane of the antelope which turns its back to the viewer. The viewer cannot see what the animal is observing. Yet, as the shadows suggest the beginning of the day, it may as well be admiring the sunrise. After all, why should we humans be the only ones to appreciate it?

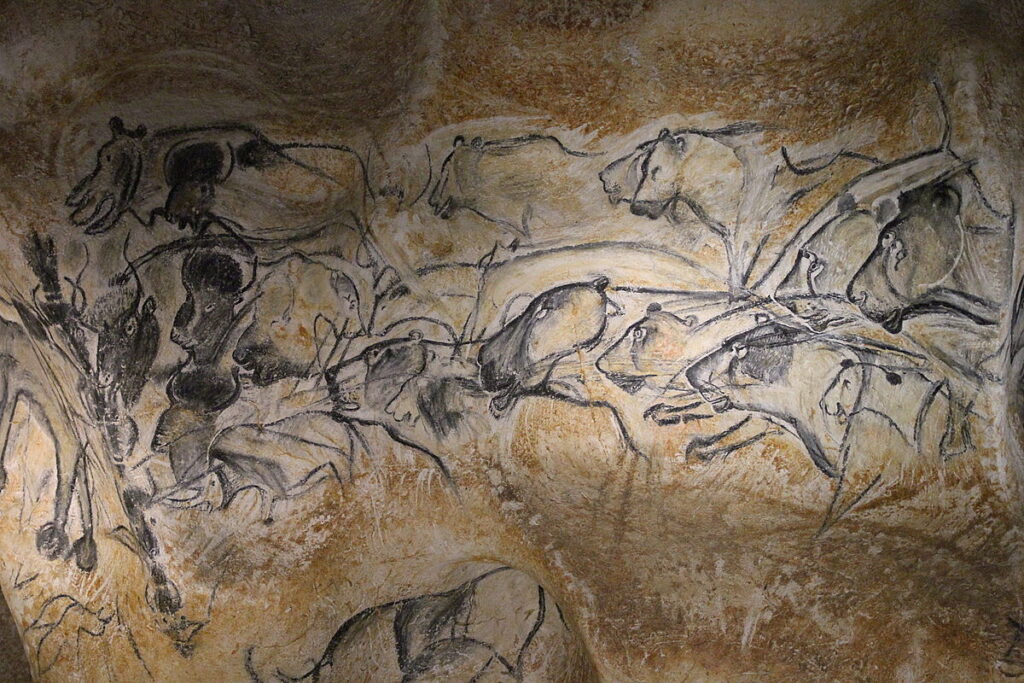

The Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave

Discovered in 1994 by a group of speleologists, the Chauvet Cave appeared to be twice as old as the famous Lascaux Cave. An exact replica of the cave is open to the public but only a few had the privilege to step into the real site. Among them is the film director Werner Herzog whose movie Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) tries to recreate the experience with 3D cameras.

For Herzog, the people who painted the hundreds of animal figures used the depth of the cave as well as the irregularity of the rocky wall to create a feeling of movement, which he calls proto-cinema.

This interpretation adds up with all the other ones. To this day, no one has been able to identify the purpose of prehistoric cave art such as Chauvet’s. Was it religious? Purely aesthetic? Or even scientific? One thing is for certain, these powerful yet fragile creatures made out of charcoal keep fascinating.

If this oil painting looks familiar, it is because it was done after Albrecht Dürer’s (1471-1528) most celebrated Young Hare. In fact, Hans Hoffmann is mostly known for his ability to imitate the Renaissance Dutch Master while still keeping his own style.

Going beyond Dürer’s photographic precision, Hoffman gives a bit more liveliness by introducing the animal into a natural environment. Yet the scene remains strange. Compared to the meticulous treatment of the plants and animals accompanying the rodent, the background seems fake. The plants themselves don’t appear to be growing from the ground, but set on it. Moreover, it is unlikely to find Lady’s Mantle, Harebell, and Thistle in the same place.

By combining together different elements of the natural landscape, Hoffman created an idealized pastoral scene using still life genre codes. Still, this work cannot be defined as such. Here, the animal is alive, evolving in nature instead of being suspended by a hook in a kitchen.

We couldn’t talk about animals without rabbits, those adorable furry creatures. And what is more cute than one rabbit? A family of rabbits! In Western tradition, rabbits have usually been a pretext for artists to show off their skill. It must be said that it is quite a challenge to imitate the soft texture of the animal’s fur.

In this painting Norval Morisseau (1932-2007) didn’t focus on the materiality but rather on the spirituality of the animal. Each body is synthesized into black shapes, contrasting with the bright colors of the different blocks inside it. The simplicity of the composition combined with vivid color contrast gives a powerful energy to the image.

Native Canadian, Norval Morisseau developed his artistic style without any other influences than Ojibwa stories, legends, and shamanism. The artist didn’t just paint images. He used secret symbols from his culture that he believed were themselves charged with secret energy once put on the canvas.