Masterpiece Story: The Rainbow Portrait

Queen Elizabeth I is known throughout history as one of the most famous British Queens. Even without a husband, she successfully ruled England for 45...

Anna Ingram 8 July 2024

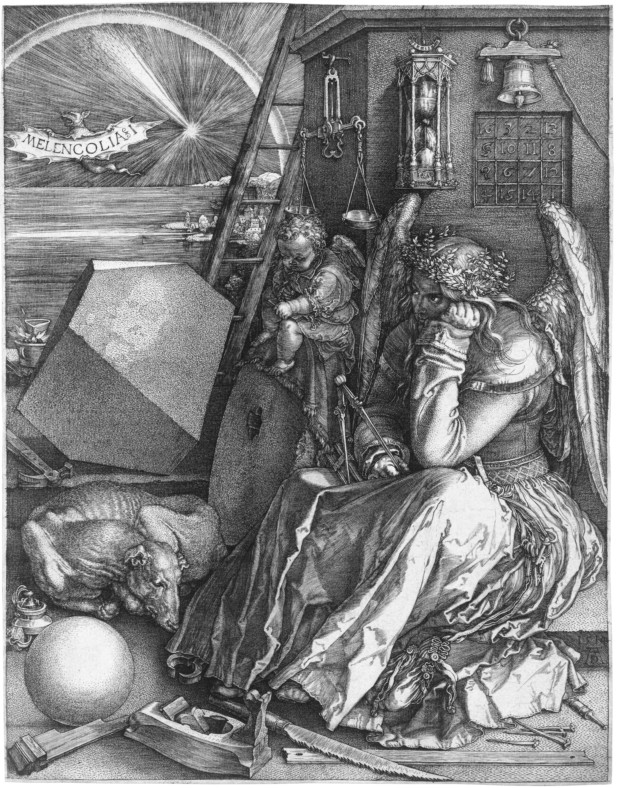

A renowned print, famously titled “Melencolia I” and crafted by Albrecht Dürer, stands as one of the most captivating works in art history. Within this unassuming monochromatic masterpiece, a plethora of symbols and significances lie encoded. Are you prepared to unveil all of its enigmatic secrets?

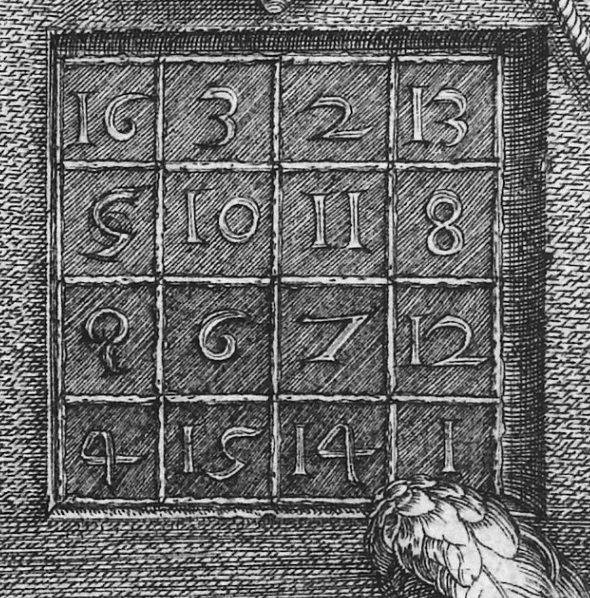

The title of the print comes from the archaically spelled “melancholy”, Melencolia I, appearing within the engraving itself. It is the only one of Dürer’s engravings to have a title on the plate. The date 1514 appears in two places – in the bottom row of the magic square and above Dürer’s monogram at the bottom right. It is likely that the “I” refers to the first of the three types of melancholia defined by the German humanist writer Cornelius Agrippa. In this first type, called Melancholia Imaginativa, ‘imagination’ predominates over ‘mind’ or ‘reason’. Creativity in the arts was the realm of the imagination, considered the first and lowest in the hierarchy of the three categories of genius. The next was the realm of reason, and the highest was the realm of spirit.

Melencolia I is an allegorical composition that has been the subject of many interpretations. There are two main ones:

Some art historians suggest that the image references the depressive or melancholy state. There are a couple of symbols that can suggest this:

An autobiographical interpretation of Melencolia I has been suggested by several historians, like art history superstar, Erwin Panofsky. According to this interpretation, the print may be a representation of the artist beset by a loss of confidence. Shortly before Dürer drew Melencolia I, he wrote: “What is beautiful, I do not know.”

In medieval philosophy, each individual was thought to be dominated by one of the four humors. Melancholy, associated with black gall, was the least desirable of the four, and melancholics were considered the most likely to succumb to insanity.

Renaissance philosophy, however, also connected melancholy with creative brilliance. Consequently, while this notion transformed the perception of this temperament, it also instilled in the self-aware artist a profound awareness of the formidable risks inherent in their talent. The winged embodiment of Melancholy, seated in a state of despondency with her head resting on her hand, grasps a caliper and is surrounded by various instruments associated with geometry. Geometry is one of the seven liberal arts that form the foundation of artistic creation, and it was through this discipline that Dürer, perhaps more so than many other artists, aspired to attain excellence in his own work.

It would be ironic if this portrayal of the artist, immobilized and impotent, were to epitomize Dürer’s own artistic prowess at its zenith.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!