The Story of Cupid and Psyche

In the Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass), Apuleius tells the story of Cupid and Psyche. Venus was jealous of the the princess Psyche’s beauty and decided to take revenge on her by making her fall in love with the worst mortal man. She instructed her son Cupid to carry out her plan. However, he fell in love with the princess himself and they secretly married.

Cupid came to his wife only under the cover of darkness and forbade her to look at him. Nevertheless, one night, Psyche came to the bedroom to see him sleeping. A drop of oil that accidentally dripped from Psyche’s lamp awakened Cupid. Angry with his wife, he left her.

Driven by love, Psyche embarked on a quest to find Cupid, eventually locating him in the realm of Venus. In a bid to humiliate her, Cupid’s mother set forth challenging and perilous tasks. With the aid of other gods and the forces of nature, Psyche successfully overcame these challenges. Ultimately, the gods bestowed upon Psyche the gift of immortality, allowing her and Cupid to share an eternal life of love.

Antonio Canova

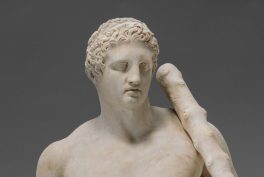

Antonio Canova worked at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries during the era of Neoclassicism in Western Europe. The philosophy of the Enlightenment, the discoveries made as a result of the excavations of Herculaneum (since 1738) and Pompeii (since 1748), and the ideas of the German art historian Johann Winkelmann influenced the emergence of Neoclassicism. In his works, including the Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture, Winkelmann formulated the basic principle of art – orientation to antiquity and its imitation. This had a big impact on many painters and sculptors of that period, who created their works in accordance with Winkelman’s theory. Being a representative of Neoclassicism, Canova filled his works with ancient Greek and Roman subjects: Daedalus and Icarus, Orpheus and Eurydice, Perseus, Venus, Cupid and Psyche, etc.

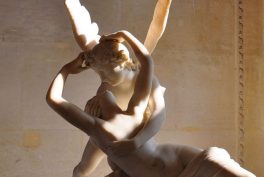

Cupid and Psyche is the theme that Canova reproduced in various forms. Firstly, he created the famous Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, and later, its second version which is now displayed in the Hermitage Museum. Soon, Canova again turned to the story and created sculptural composition Cupid and Psyche, again in two copies which are now displayed in the Hermitage and the Louvre.

In this work, Canova depicted the characters standing and wingless. The sculptural group Cupid and Psyche is more static, precisely because of the lack of wings. Canova masterfully worked with the material and composition bringing the feeling of lightness and youth. The pair represents tenderness and innocence. Cupid embraces Psyche, who puts a butterfly in his hand. For the ancient Greeks, a butterfly symbolized the soul. In addition, both characters are immersed in contemplation of an allegorical butterfly, thus giving the impression of quiet beauty.

Bernini School

Antonio Canova is not the only sculptor who depicted Cupid and Psyche. Baroque artists were no exception. Art of the Baroque era was penetrated by theatricalism, emotionalism, and exaggeration. Both painters and sculptors used spiral lines, emphasized expressions of emotions, and avoided tranquility.

At the end of the 17th century, a sculptor of the Gian Lorenzo Bernini school, presumably Giulio Cartari, created the sculptural composition Cupid and Psyche. According to Apuleius, it was forbidden for Psyche to see Cupid’s face, however, she crept up to her sleeping lover with a lamp in her hands, a drop of hot oil from which was about to wake Cupid up. This moment was depicted by the sculptor with virtuosity. In this sculptural group, Baroque manifests itself through movement, theatricality, and spiral composition. The folds on the clothes and the bed, and the slipping drapery of Psyche create the illusion of movement. The poses of the characters unwind the composition spirally, starting at Cupid’s feet and ending with Psyche’s hand raised above her lover’s head.

Theodor Friedl

In the 19th century, the Austrian sculptor Theodor Friedl also took on the story from Metamorphoses. It is known that Friedl studied under the sculptor Anton von Fernkorn, who rediscovered the Baroque style for Vienna. Around 1890 Theodor Friedl created the sculptural group Cupid and Psyche in the Baroque manner. The composition of Cupid and Psyche is dynamic: the drapery slides off Psyche’s body and Cupid is depicted in the moment of flight, with his wings spread, ready to pick up Psyche and fly away with her. Having studied the Baroque art, including Bernini’s sculpture, as well as the work of Anton von Fernkorn, Friedl made the seemingly impossible: gave the stone movement and the effect of a caught moment.

Johan Tobias Sergel

Swedish sculptor Johan Tobias Sergel, like Antonio Canova, worked in the Neoclassical style in the 2nd half of the 18th century. Following the rules of Neoclassicism, he endowed the sculptural group with harmony and quietness even though he depicted Psyche in the dramatic moment, praying for Cupid to stay. We can see the lamp near her knees, which tells us the moment followed her observation of Cupid sleeping. Sergel shaped the axis of the composition through Cupid’s almost still body. This work manifested Neoclassical ideals, indifferent to vortices and spirals, as well as the vivid drama of the Baroque.

Summing up the comparison of several sculptural groups of this subject matter, attention should be paid to the following: despite the inherent theatricality of Baroque sculpture, Neoclassicism is not devoid of movement and natural feeling either. Sculptures of Cupid and Psyche, created by Antonio Canova and Johan Tobias Sergel are not perceived by the viewer as static, but rather filled with a smooth and gentle energy between depicted characters and a calm atmosphere, without additional drama.