Summary

- Constance Mayer started her career studying under Jean-Baptiste Greuze, a painter of sentimental genre scenes, but she eventually shifted to a more emotionally driven art.

- With influences from Jacques-Louis David, Mayer took up a cool, Neoclassical style and started to explore more serious subjects.

- Mayer joined the studio of Romantic painter Pierre-Paul Prud’hon. The two artists made art together with mutual respect. Prud’hon created sketches that Mayer then painted onto the canvas with her own interpretation.

- Mayer did not focus on just one subject. She painted sensual mythological themes but also portraits, particularly of women.

- Her later paintings, like The Dream of Happiness, can be seen as proto-Romantic with their dramatic use of light and emotional charge.

- Mayer died by suicide, which might have been affected by her tragic romantic involvement with Prud’hon. For a long time, she was erased from art history, and her work has been miscredited to Prud’hon despite the latter’s respect for her legacy.

Constance Mayer, the Student

Constance Mayer was born in the 1770s into a well-to-do Parisian family, who seem to have encouraged her ambitions to become an artist. We know little about her early life, but given that her father was a government official in the capital, she must have been affected by the French Revolution. Her first art tutor was actually imprisoned during The Reign of Terror of 1793-1794. Sometime during the mid-1790s, Mayer joined the studio of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, a prolific and popular producer of sentimental genre subjects. Greuze ran a large studio with a number of female students, including Mayer’s close friend Jeanne-Philiberte LeDoux, who also had a successful career as a painter of children.

Greuze’s soft, reassuring domestic scenes were an escape from the political and social trauma of the period. His moralizing images of God-fearing happy families, good mothers, and idealized children were full of observed detail and busy action, designed to involve his audience.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Spoiled Child, 1760s, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

None of Mayer’s paintings from this period have survived, although they were described as being very close to Greuze’s own style. We know that after her death, a number of works were cataloged as the “studio of Greuze” but were probably painted by Mayer herself. While she was working with him, she achieved considerable success, exhibiting a range of works, including miniatures, portraits, and genre scenes at the Paris Salon from 1796.

She continued to paint similar subjects throughout her career. Her last unfinished picture, The Grief-Stricken Family (1821), portrayed a miserable attic scene with a poor family mourning the loss of a child. The Happy Mother (1810) and The Unfortunate Mother (1810) show how Mayer successfully moved away from Greuze’s fussy compositions to develop her own style of pared-down, emotionally-driven genre. In The Happy Mother, a woman is breastfeeding her baby. The woodland setting emphasizes the naturalness of the bond between them. The soft backlighting, creating a halo-like effect, implicitly reminds us of Madonna and Child.

Constance Mayer, The Happy Mother, 1810, Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

The Influence of Jacques-Louis David

During 1801, Mayer spent some time in the studio of Jacques-Louis David. David was the most famous painter in France at the time, the founding father of Neoclassicism, and a leading figure of the Revolution. Neoclassical art aimed to return to the ideals of the ancient world, with idealized drawings from the nude, morally and politically serious subjects, high finish, and subdued tones designed to appeal to the intellect rather than the emotions. David’s style was exemplified by The Death of Marat (1793), almost the exact artistic opposite of Greuze’s softly painted, pastel-colored sweetness, with its stark, plain background, hard-hitting subject, and rectilinear composition.

Constance Mayer, Self-Portrait of the Artist with her Father, 1801, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CO, USA.

The self-portrait which Mayer exhibited at the 1801 Salon shows the immediate impact of David on her work. She represents herself and her father with a bust of Raphael and fragments of classical sculpture, emphasizing that she wants to be taken seriously as part of an academic art tradition. The studio setting is bare, stripped of all Greuze’s fussy detail. The palette is cool and unemotional.

The painting shows how self-aware and ambitious Mayer was. She represents herself in the plain Grecian style, which was the height of Revolutionary fashion, a deliberate reaction to the elaborate excess of 18th-century court dress. Previously, she had exhibited a self-portrait entitled Citizeness Mayer. In both cases, she is saying: “I am a radical, modern woman.” She shows herself opening her own folder of sketches, emphasizing her active role as a producer of art. And she is not afraid to be ambitious, suggesting she is capable of emulating Raphael, who was considered the greatest artist of all time.

However, we see how carefully she had to position herself, as a woman in what was essentially a man’s world. She was very close to her father, and in one sense, this is a personal tribute to him and the support he had given her. Yet, he also represents a safe male presence who is guiding her in her career and to whom she is deferring. He is the one at the center of the composition, who is directing her towards Raphael.

Constance Mayer, A Muse, c.1800, Wikipedia Commons (public domain).

Mayer and Prud’hon

In 1802, Mayer began working in the studio of Pierre-Paul Prud’hon. He was sixteen years older than her, and arguably the more famous artist, but he was in a rut. Never very productive, Prud’hon preferred drawing to painting and frequently found it difficult to finish compositions. Stylistically, his works retained a soft smokiness that was seen as old-fashioned in an art world dominated by David.

Mayer herself was too established of a painter to be just a student. From the start, their relationship seemed one of mutual respect and collaboration. Mayer gave Prud’hon a new impetus and direction. Equally, he gave her a cloak of masculine respectability which allowed her to pursue the painting career she wanted.

Constance Mayer and Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, Innocence Preferring Love to Fortune, 1804, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Innocence Preferring Love to Fortune was exhibited at the 1804 Salon under Mayer’s name but has since frequently been cataloged as a painting by Prud’hon. In fact, like many of their works, it is collaborative. Prud’hon had been thinking about the subject and the composition for years: there are at least 12 preparatory sketches by him. Allegorical subjects, in which figures were used to represent ideas, fascinated him. But it was Mayer who put the paint on the canvas. It was quite common for students to paint part of a picture, usually less important areas like draperies. This is not what happened here. Prud’hon handed the idea over, giving Mayer free reign to interpret it.

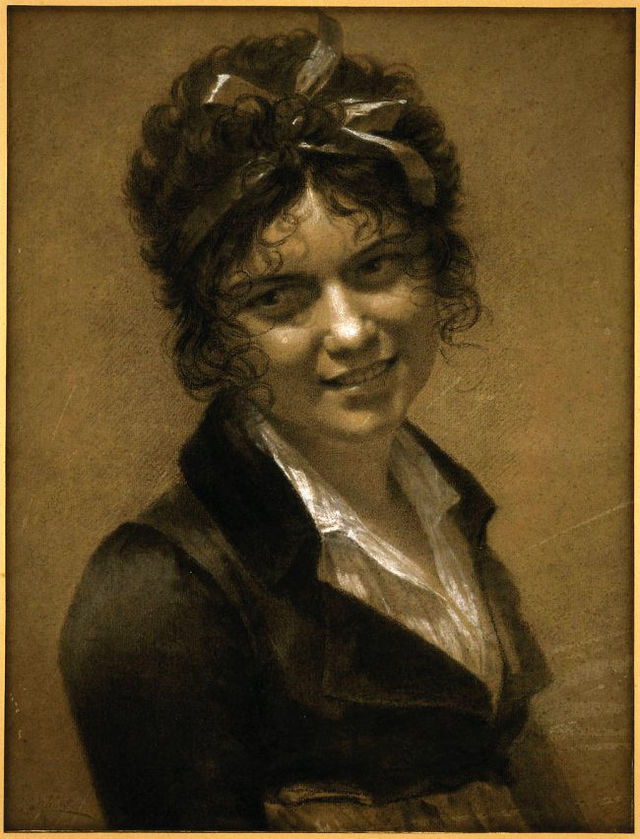

Pierre Paul Prud’hon, Constance Mayer, (chalk) c.1804, Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Their relationship had another dimension. Prud’hon had a chaotic domestic life, six children, and a difficult marriage. In 1803, his wife was admitted to an asylum. Mayer seems to have stepped in as housekeeper, nanny, and general assistant. It is easy for us to assume that their relationship was also sexual, although there is no direct evidence. They never lived together and they destroyed their letters.

Yet, as Prud’hon’s intimate chalk portrait of Mayer shows, they were clearly very close. Mayer is laughing, open-mouthed with real affection in her eyes, and Prud’hon has lavished enormous care on naturalistic details like the curls bouncing around her face.

Mayer, the History Painter

Constance Mayer, The Sleep of Venus and Cupid, 1806, Wallace Collection, London, UK.

At the time Mayer was working, the so-called “history painting” of mythological and classical themes was considered the highest form of art. Women were thought to be too emotional and unintellectual to undertake it. And because it involved the representation of the nude, it was considered unsuitable.

It is clear that Mayer had ambitions to be a history painter and working with Prud’hon allowed her to achieve her aim. In 1806, Mayer was commissioned by Empress Josephine to paint The Sleep of Venus and Cupid. It was arguably the high point of her career, a large-scale history painting, completed entirely by her, for a prestigious client.

It also shows how much Mayer had developed from her days in Greuze’s studio. The warm, rich tones and soft, sfumato shading show the influence of artists like Correggio who Prud’hon greatly admired from his time spent training in Italy. Like much of Mayer’s work, it is deeply sensual, not just in the positioning of the female figure, but in the way the light falls on the flesh.

Portraits

Constance Mayer, Amable Tastu, c.1817, Musee de la Cour d’Or, Metz, France.

Unlike many women artists, Mayer seems determined not to have been pigeonholed or restricted in her range of subject matter. She was a successful portraitist, particularly of women. Amable Tastu, a well-known poet who was also a friend, is represented as a Romantic heroine in Mayer’s 1817 canvas. She sits, holding one of her compositions, her chin resting on pensive fingers, looking out with a faraway look in her eyes as if she is seeking inspiration. The dark, tree-filled landscape behind acts as a foil to her almost luminous white gown, the red shawl giving a sense of life and passion lurking underneath her fashionable pale skin.

Proto-Romanticism

Constance Mayer, The Dream of Happiness, 1819, Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Tastu’s portrait, like The Happy Mother, sees Mayer exploring the effects of light and landscape for dramatic and emotional effects. Her most ambitious painting, The Dream of Happiness (1819), uses strong chiaroscuro and a stormy moonlit sky. It is a work of contrasts. The female figure is dreaming peacefully, cradling her child, yet has an almost ghostly paleness. The boat is drifting down the river of life guided by Fortune and Love, but the draperies blow threateningly in the gathering wind. Maybe happiness is only a dream.

Mayer’s work can be seen in the context of the new Romantic emphasis on emotion and mood. Artists and writers were turning away from an interest in classical subjects and the Enlightenment’s belief in the power of reason. Optimism was replaced by new doubts. Alongside The Dream of Happiness at the 1819 Salon hung Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa.

Mayer’s Tragic Death

The painting also perhaps reflected the uncertainties of Mayer’s personal life. She was suffering from depression, worried about getting old, and increasingly dissatisfied with her relationship with Prud’hon. French law did not allow divorce, even though Madame Prud’hon was in an asylum. The artist’s children resented Mayer and blamed her for their mother’s illness. She had also spent considerable amounts of her own money supporting his family. Prud’hon’s wife died in 1820, leaving the artist finally able to remarry. Whether she was already his mistress or not, Mayer clearly expected to become his wife. Prud’hon was adamant that he had no intention of re-marrying. In 1821, taking his razor, Mayer cut her own throat.

Constance Mayer, Phrosine and Melidore, Musee Magnin, Dijon, France.

Prud’hon completed Mayer’s final canvas, exhibited it in the 1822 Salon, and organized an exhibition of her work in tribute to her. He died himself only two years later, perhaps unable to cope with the loss of his long-time companion and helper. In the years after her death, Constance Mayer was effectively written out of history. Any works which she and Prud’hon had collaborated on were ascribed to him, as were most of those entirely by her own hand. This was partly about money – his pictures sold for more – and partly about art historical prejudice which assumed the older, male artist was the “genius” and the younger woman could only be a mere assistant.

Constance Mayer, Self Portrait, c.1801, Bibliothèque Marmottan, Boulogne-Billancourt, France.

Better Together

For feminist art historians like Germaine Greer, who wrote about her in The Obstacle Race (1979), Mayer became almost a martyr figure. Misused, sexually exploited, and unappreciated, she was literally “engulfed” by the predatory older man. At best, she was besotted by him. At worst, she was groomed. Her 1801 Self-Portrait seemed evidence of a confined and miserable existence. Yet, it seems obvious that Mayer was a determined and capable woman: financially independent, artistically ambitious, and well aware of the benefits which working with Prud’hon could bring. It also seems clear that they were very close, partners in every sense of the word. Until the tragic events of 1821, they enjoyed 20 years of successful collaboration.