Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

20 February 2024 min Read

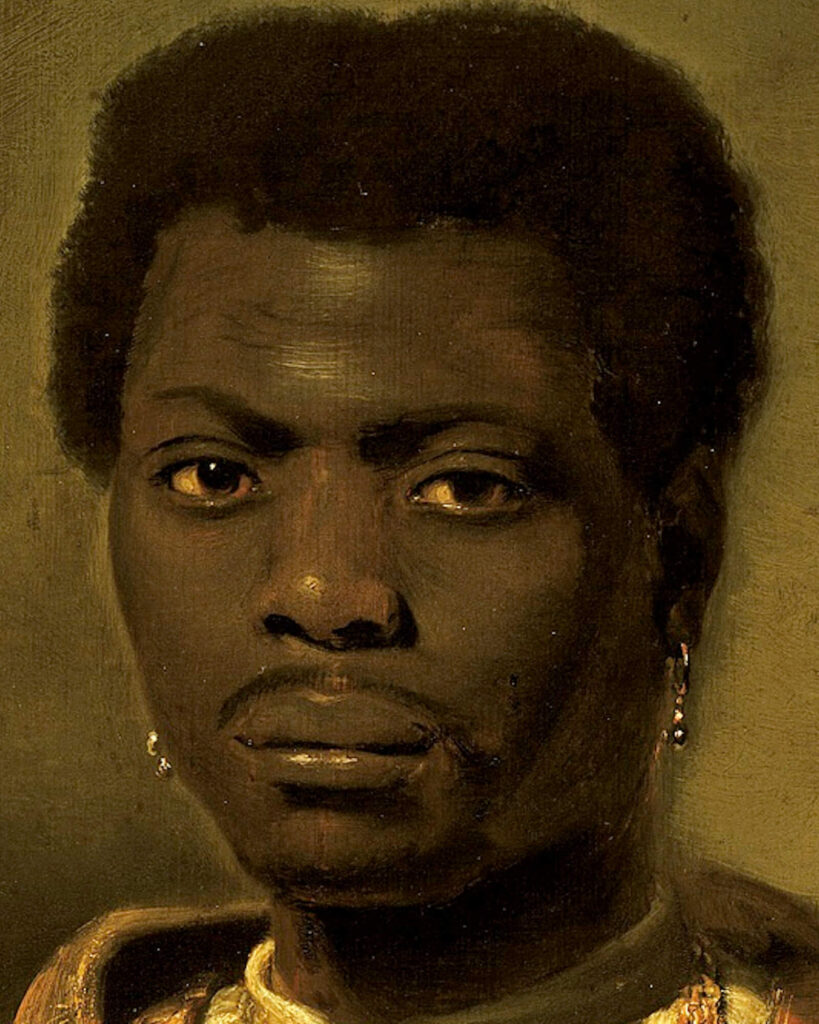

White subjects have dominated the Western art tradition for millennia, while people of color have been vastly underrepresented and misrepresented. The Dutch Golden Age is no exception. However, it has some sparkling examples of when people of color were portrayed in a noble, positive, and elevated light. For example, Hendrik Heerschop, a little-known artist, painted one such image: The African King Caspar. It is a dramatic break from the white elite and the domestic scenes that typically dominate the Dutch Golden Age. That is to say, Hendrik Heerschop’s The African King Caspar is a piece of social complexity.

The birth of the Dutch Republic in 1581 to the Rampjaar (Disaster Year) in 1672 commonly marks the Dutch Golden Age. It was a time when the Dutch Republic was among the leading nations for art, trade, science, and military. The art world boomed as countless artists, Hendrik Heerschop among them, produced countless paintings. Anyone with good finances and with a sense of posterity could commission portraits. Anyone with spare income and with a sense of beauty could acquire landscapes. So, even those with limited means and with a sense of hope could buy prints. This was a time when the art world penetrated all levels of society from the wealthy to the poor. That is to say, there was literally some form of art for everyone. However, despite art’s wide-appeal and wide-availability, people of color were still dramatically few.

The white elite dominated the Dutch Golden Age. People of color were rarely included, and when they were mostly were portrayed, it was as slaves and servants relegated to the background. This is why Hendrik Heerschop’s The African King Caspar is such an exception. For example, there is no white dominating or lording over the African man. The king sits proudly with dignity and grandeur. He is not a lowly domestic, but instead he is an honorable African king.

The African King Caspar depicts the Biblical King Caspar from the Adoration of the Magi. In the Biblical story, three wise kings, or magi, approached the infant Jesus with gifts. King Melchior, the oldest magi, brought gold to represent the infant’s regality. The second oldest magi, King Caspar, brought frankincense to represent the infant’s divinity, while King Balthasar, the youngest magi, brought myrrh to represent the infant’s humanity. Hendrik Heerschop’s The African King Caspar depicts the magi holding his gift of frankincense. It is inside the precious vessel between his hands.

What is ultimately sad about Hendrik Heerschop’s The African King Caspar is that we know so little about the artist and the sitter. We know Hendrik Heerschop worked in Haarlem, Netherlands. He created genre scenes, and painted in the style of Haarlem classicism. The sitter, however, is unknown. History has forgotten his name.

On the other hand, what we do know is that the depicted in The African King Caspar has the facial features of a specific individual. That is to say, this African man is not a generic composition (tronie). He is not an idealized or imaginary model. Slavery was not allowed in the Netherlands during the 17th century, therefore the African sitter was free and may have been a neighbor or an acquaintance of the artist. This probably means what we have in The African King Caspar is a free African man being painted in the guise of an African king by a white Dutch artist who specialized in genre scenes.

Since The African King Caspar is not the portrait of a living African king, it does not have the same social prestige and recognition as a commissioned European royal portrait. There is one exception of a portrait of an African official from the 17th century that you can read about here. Consequently, it is a rare piece of historical, social, and artistic importance. Like women, people of color have been marginalized in art books, class lectures, museum collections, and social dialogue for too long. I hope recognizing the beauty found in The African King Caspar will be another step towards this collective recognition and reevaluation.

P. Bakker. Pieter De Grebber. The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2017 [Accessed June 20, 2020].

N. Siegal. Dutch Golden Age Art Wasn’t All About White People. Here’s the Proof. The New York Times, March 13, 2020 [Accessed June 20, 2020].

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!