An Homage to Tadeusz Rolke in 10 Photographs

Tadeusz Rolke, hailed as an icon and legend of Polish photojournalism, died in his native Warsaw in July 2025, at the age of 96. He dedicated his...

Guest Author 6 October 2025

Artist Carrie Mae Weems was born in Portland, Oregon, USA. Now in her seventies, she is still actively working, and is considered one of America’s most important photographers. Her Kitchen Table Series was produced over a year from 1989 to 1990. Every day, she took photographs in her own kitchen, centered around a plain wooden table. These unique representations of domestic life in photographs are perhaps Weems’ best-known work.

Consisting of 20 photographic prints accompanied by 14 text panels, Carrie Mae Weems‘ Kitchen Table Series has come to possess immense significance. As well as being in and of themselves beautiful works of art, the images are also a message to all of us, but especially to women artists and to artists of color, that representation matters.

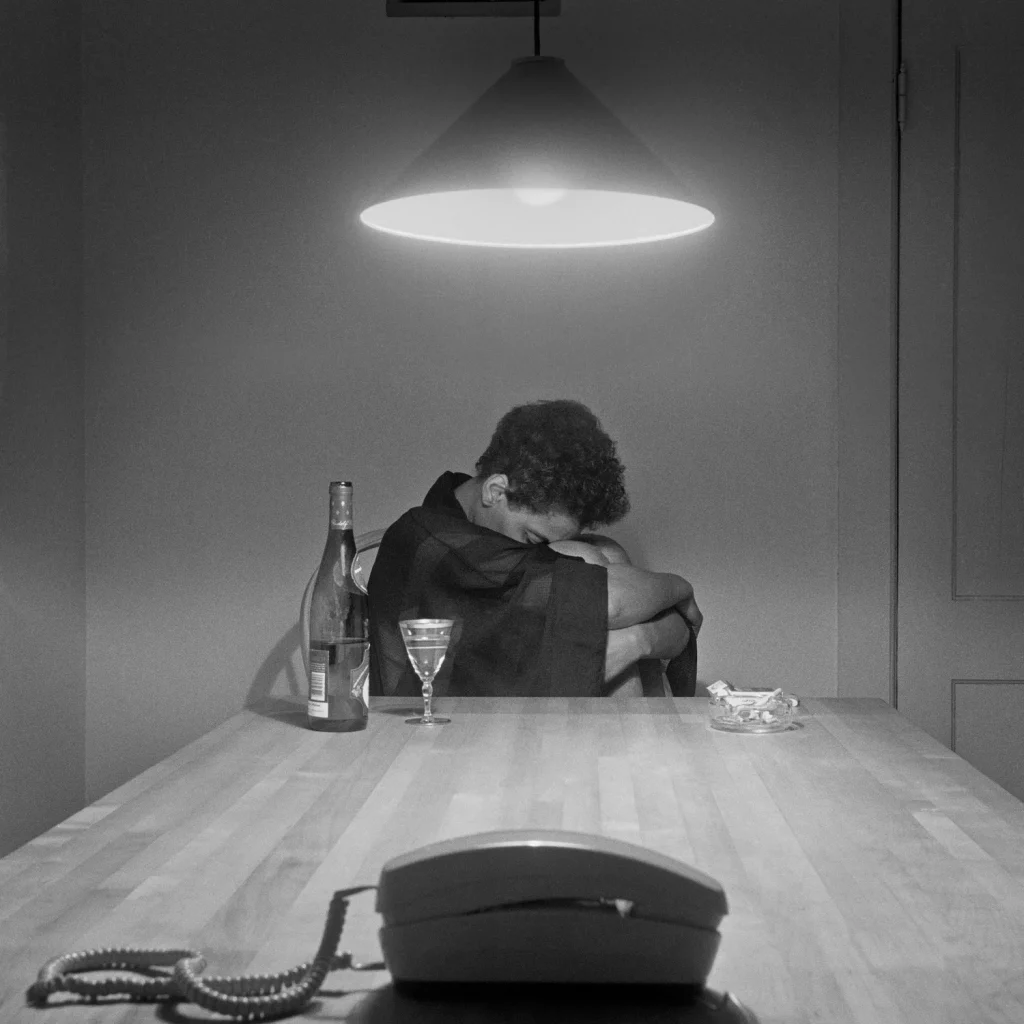

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Man Smoking), 1990. Artist’s website.

This is a rare chance to look deep into women’s lives. A series of black and white photographs witnessing, recording, and celebrating a sacred space. This is where the strong family bond of African American communities is seeded. Quite literally, where it is fed. Each image asks questions of us. The artist is giving voice to important and vital parts of life that have previously been considered unimportant. Weems is exploring huge social issues: race, gender, parenting, love, and identity. But she is also showing us the small, ordinary objects and intimate moments that make up the details of life. Weems called this “making the invisible visible.”

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Children), 1990. Artist’s website.

Historically, in art as in life, Black communities have been seen as scientific specimens, anthropological subjects, or sexy exotica. To steal a reference from the gaming world, they are seen as NPCs—non-player characters, quietly filling in the space behind the main (white) action. Think of the Black maid in Edouard Manet’s painting Olympia. Or the anonymous men in Robert Mapplethorpe’s Black Male series.

The history of photography consists mainly of images taken by white photographers for white audiences. In this sense, photography is like so many other art history narratives, characterized by exclusion and oppression. Weems adored the work of so many artists through history, but she was acutely aware of their blind spots.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Woman with Friends), 1990. Artist’s website.

I cannot rely on these artists and they have disappointed me greatly. As much as I love them and revere them, I am also very, very disappointed with their engagement of the historical body of the Black self, the Black body, the Black imagination.

Interview with Carrie Mae Weems, September 12, 2015, National Gallery of Art YouTube.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Eating Lobster), 1990. Artist’s website.

Carrie Mae Weems challenges the accepted norms of art history. She said her question was how to insert a body into the record that had not been there before, or had been pushed to the background. Her photography is the answer. We, the viewers, sit across the table, watching and witnessing as she uses her camera to tell stories about women, people of color, and the working classes. We see mother, wife, lover, daughter, friend, neighbor in powerful and poetic performances. The images are cinematic and theatrical, yet also quietly domestic and oh so ordinary.

When we come across these astonishing and iconic scenes by Weems, the impact is incredible. Highly composed, like a 17th-century Clara Peeters domestic still-life painting (see below), but also ultra-modern like a contemporary documentary film.

The location Weems chooses for this series is the key to understanding her work. The kitchen is a highly gendered space—the realm of the housewife. The kitchen can be a sanctuary, but also a cage; a haven, but also a battleground. We might be there in pleasant solitude or in painful isolation. Both harm and healing occur in this space, all of it mostly ignored by artists for centuries.

It wasn’t until female French Impressionists like Berthe Morisot and ex-pat American Mary Cassatt painted their worlds that we peeked inside the domestic sphere (see the images below). But these domestic paintings were more often the sitting room, the nursery, and the boudoir. These privileged women did not sit in their kitchens.

Carrie Mae Weems used herself in her Kitchen Table Series photographs, performing as an archetypal everywoman. When asked why she used herself as a model, her answer was simple: she was at home and she was available! This artist is very aware that the kitchen table is a stage where life’s biggest (and smallest) moments play out. The kitchen is a private yet communal space. She uses her own body as a landscape to explore the complex realities of human emotion and daily life.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Woman with Daughter), 1990. Artist’s website.

Moods change across these photos. At times, Weems is gently exploring the idea of womanhood and family. But in other images, we are more aware of that bright overhead light—the light of interrogation, with a harsher and more challenging tone. The camera is fixed in position, but the characters and their feelings can change.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Man Reading Newspaper), 1990. Artist’s website.

Work by Black artists is almost always assumed to be about “Blackness,” while a white artist is considered to be sharing truths about the universal condition. Weems has always been clear that the Kitchen Table Series is not just about race. Every woman can relate to something in this work. And every man can identify scenes from their past or present lives.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Woman and Phone), 1990. Artist’s website.

A Black female artist faces huge intersectional challenges in the worlds of art and academia, as well as in general society. Carrie Mae Weems certainly rises to the challenge—her work is triumphant!

The feminist activist and writer bell hooks explored themes of intersectionality in her book Teaching to Transgress (1994, Routledge). She explored the idea of people who were straddling two or more worlds, trying to make space for themselves. She wrote: “They must believe they can inhabit two different worlds, but they must make each space one of comfort. They must creatively invent ways to cross borders… to subvert and challenge the existing cultures.” Weems, in her life and in her art, seems to have always been striving for that.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Nude), 1990. Artist’s website.

Three decades on, the Kitchen Table Series is still so utterly contemporary. And Weems’ work continues to inspire. She is an artist who empowers both viewers and other artists. Once she got a seat at the art world table, she made it her mission to ensure that the doors are flung open and that seats are available for the artists who come after her. We will end with a wonderful poem about the kitchen table by Joy Harjo, poet and performer, of the Muskogee (Creek) Nation.

Carrie Mae Weems, Kitchen Table Series: Untitled (Woman Standing Alone), 1990. Artist’s website.

The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat to live.

The gifts of earth are brought and prepared, set on the table. So it has been since creation, and it will go on.

We chase chickens or dogs away from it. Babies teethe at the corners. They scrape their knees under it.

It is here that children are given instructions on what it means to be human. We make men at it, we make women.

At this table we gossip, recall enemies and the ghosts of lovers.

Our dreams drink coffee with us as they put their arms around our children. They laugh with us at our poor falling-down selves and as we put ourselves back together once again at the table.

This table has been a house in the rain, an umbrella in the sun.

Wars have begun and ended at this table. It is a place to hide in the shadow of terror. A place to celebrate the terrible victory.

We have given birth on this table, and have prepared our parents for burial here.

At this table we sing with joy, with sorrow. We pray of suffering and remorse. We give thanks.

Perhaps the world will end at the kitchen table, while we are laughing and crying, eating of the last sweet bite.

Joy Harjo, poem from The Woman Who Fell From the Sky, 1994, WW Norton and Company.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!