Summary

- Art historian Rose Valland began working at the Jeu de Paume museum in 1932. She oversaw the works kept in the museum’s basement while much of France’s art was evacuated during World War II.

- A secret program aiming to confiscate private artworks and Jewish collections was launched by the Nazis after they occupied France. Valland stayed with the Jeu de Paume, observing and recording the looted art.

- Valland created an archive that tracked the destination of the stolen masterpieces, including those that were not officially approved by Third Reich.

- With the Allies, Valland tracked a convoy during the German retreat. She managed to recover the entirety of the museum’s collections.

- Valland teamed up with the Monuments Men after Paris was liberated and later served in Germany as a Fine Arts officer to return looted artworks to their rightful owners.

- After returning from Germany, Valland became the curator of France’s National Museums and published her memoir, a crucial account of preserving Europe’s cultural heritage.

A Life in Art

Born in a small rural village in southeastern France, Rose Valland showed an early interest in art. In 1918, she began formal studies in Lyon. Like many artists, she then moved to Paris, the then-epicenter of the art world, where she earned degrees in art and art history from the École Nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the École du Louvre, and the Sorbonne.

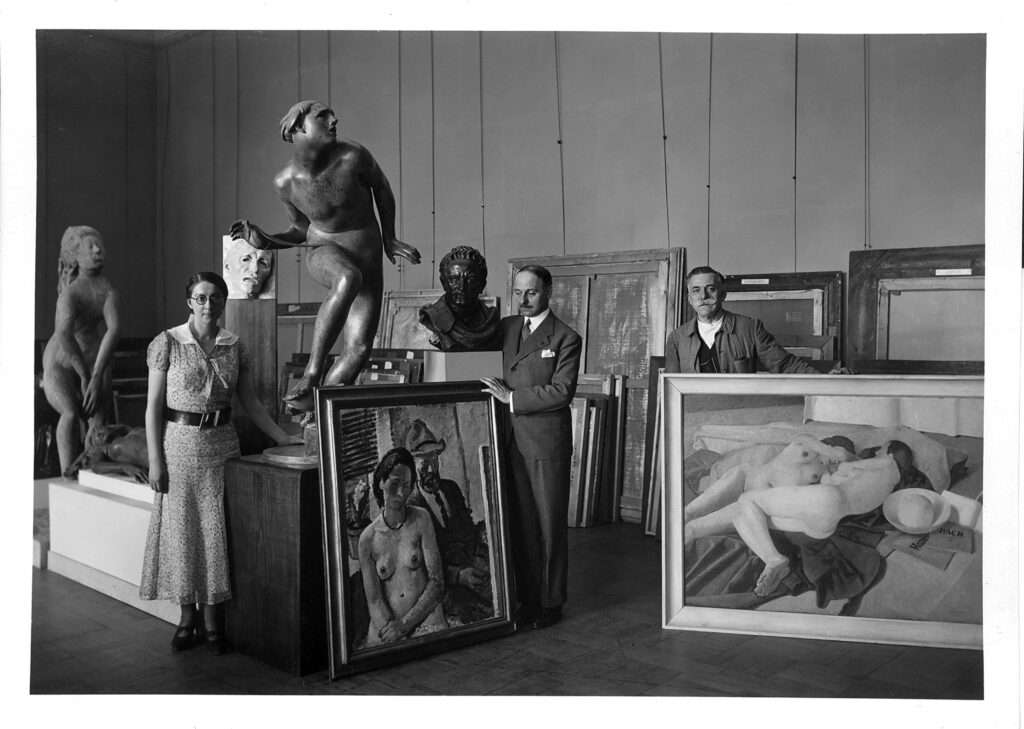

Rose Valland, André Dézarrios and an attendant during the installation (or deinstallation) of the exhibition Italian art of Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries at the Jeu de Paume Museum from May to July 1935. Photo: Archives nationales, France, 20144707/289 (box no. 1). Courtesy of Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

In 1932, a job opening at the Jeu de Paume in the Tuileries Garden near the Louvre offered her a step toward fulfilling her dream. She began working as an assistant, taking care of its collections of foreign contemporary art. It was an unpaid position, but she was determined that things would change once she had proven her worth. And they did. Though in ways she could never have imagined.

Packing the Louvre

On May 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler unleashed his forces on Western Europe. As early as war was declared in September 1939, Jacques Jaujard, director of the National Museums, launched a preemptive evacuation of France’s national art collections. As paintings and sculptures had to be prepared and packed on-site, the Louvre turned from a sanctuary of art into a massive packing yard. This also proved to be a considerable challenge, especially with monumental works including the Nike of Samothrace and oversized canvases. The artworks were afterward transported to countryside châteaux. Château de Chambord was one of them that served as the main depot.

Rose Valland oversaw the Jeu de Paume’s collection. As a smaller institution, only a portion of its works could be relocated. The rest were hidden in the museum’s basement, as staff watched events unfold with growing anxiety.

The Nike of Samothrace being removed from the Louvre in August 1939. Pierre Jahan, Archives des museés nationaux. ResearchGate

A Secret Plan for Plunder

All the while France was reeling from occupation, the Nazis were plotting a cultural takeover. A secret program was launched to identify and “retrieve” artworks of German origin or those loosely connected to the cultural history of the Reich. On June 30, 1940, Hitler ordered all artworks, public or private, to be handed over for “safekeeping.” German officers began inspecting depots and inventories, quietly laying the groundwork for the seizure.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Adolf Hitler admire a painting looted from a conquered territory. World Jewish Congress.

But this vast operation had been hidden from public view. The Nazis knew that if their true intentions became known too soon, their plan would have failed before it had started. As she looked back on the secrecy and subtlety of the maneuvers after the war, Rose Valland confirmed her apprehension. Had the Nazis acted sooner, nothing could have stopped them.

They would have carried out one of the greatest removals of artworks the world has ever known. Napoleon’s booty would have been paltry by comparison.

The Art Front: The Defense of French Collections 1939–1945.

Until 1942, the fate of France’s national collections remained uncertain. They were eventually recovered, largely due to Goebbels postponing the plan until after a future peace treaty. The only exception was the Ghent Altarpiece, which was taken from Château de Pau with help from the Vichy regime.

The ERR Takes Control

While France’s national collections had been saved, private collections, especially Jewish-owned, were not. The German embassy in Paris initially overseeing the seizure was soon replaced by the ERR, a Nazi task force for cultural looting backed by Göring. ERR officers started by using rooms in the Louvre to sort the art they took possession of, but space quickly ran out. They requested access to the Jeu de Paume, perfectly suited for their needs: central, secure, and discreet.

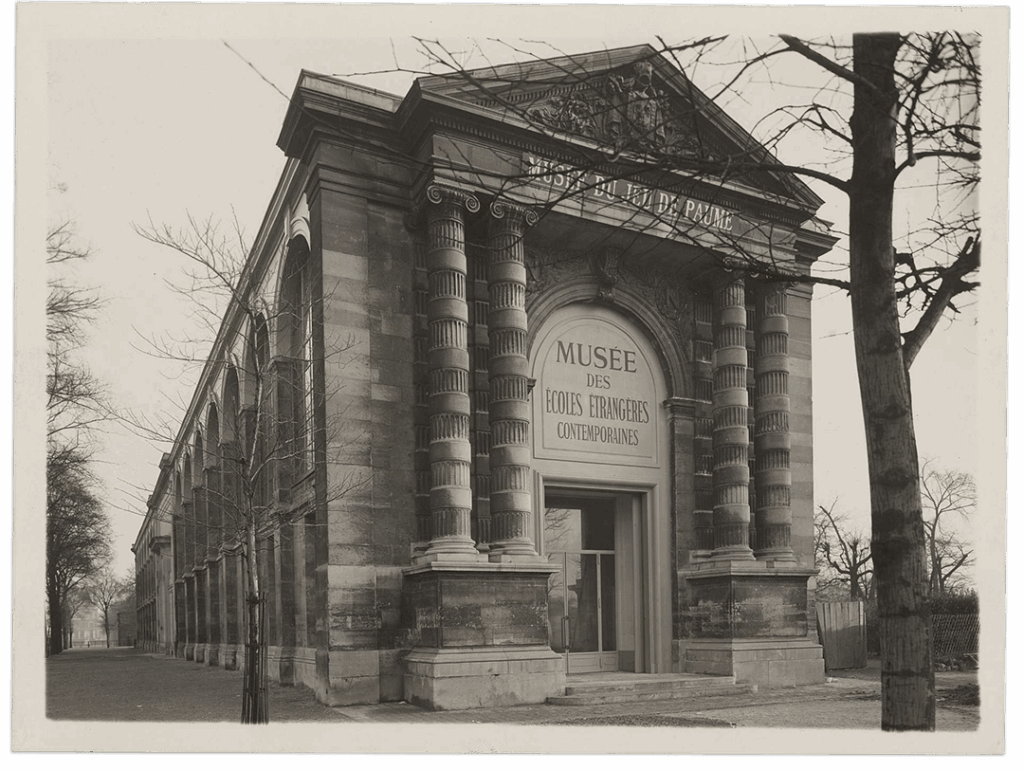

Jeu de Paume in 1933, Archives Nationales, Paris, France. Christie’s.

When the Nazis took over the Jeu de Paume, Jacques Jaujard saw a chance to keep someone inside, Rose Valland. With her deep knowledge of French collections, exceptional memory, and understanding of German, she was the right person to track the looted art. Her task was simple, observe and record without being caught. Would she accept the risk? Absolutely.

Inside the Lion’s Den

On November 1, 1940, Nazi trucks filled with looted art pulled up at the Jeu de Paume. Soldiers gained control of the museum before they began hauling the artworks to the site. Paintings were dropped, stepped on, or piled up without protection. In less than a day, over 400 crates had been brought in.

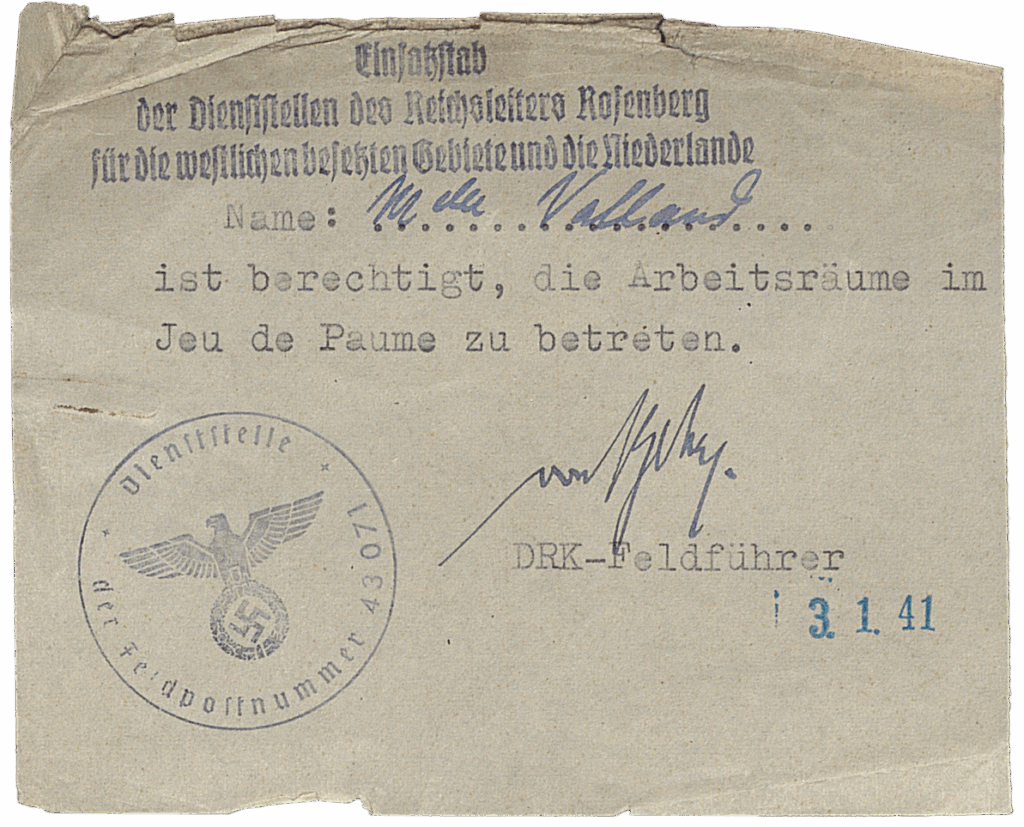

ERR access pass for the Jeu de Paume issued to Rose Valland, 3 January 1941, Archives Nationales, Paris, France. Christie’s.

That same day, Rose Valland quietly began her work. No German expert supervised her. No proper inventory system was in place. The Nazis even sent their agents to walk her out of the building, but she chose to stay. Without drawing attention, she began recording everything: what arrived, what left, and where it was sent.

The Jeu de Paume was converted into a “special concentration camp” created for works of art. Each day, new “prisoners” arrive, which only added to the surreal experience.

The Art Front: The Defense of French Collections 1939–1945.

Within months, the museum had become the central hub of Nazi looting. Valland’s secret lists included masterpieces by Vermeer, Raphael, and Velázquez. Soon came crates filled with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist treasures by Monet, Renoir, Degas, Van Gogh, Matisse, and more.

Tracking the Looted Art

At the Jeu de Paume, Rose Valland turned observation into resistance. She discreetly noted everything she saw or overheard, using any excuse to move around the building and identify artworks and their owners. Her real mission was to find out where the looted works were going. It took months to piece together scraps of information, but she was patient. Even German officials made mistakes, and those slips often revealed key details. She also chatted with French workers hired by the Nazis. Casual small talk during routine tasks often led to useful clues. Combined with her secret records of Göring’s personal visits, these fragments became crucial for tracking stolen art. She kept detailed notes and met regularly with Jacques Jaujard to share updates. Quietly, Rose Valland built the most important archive of Nazi looting in France.

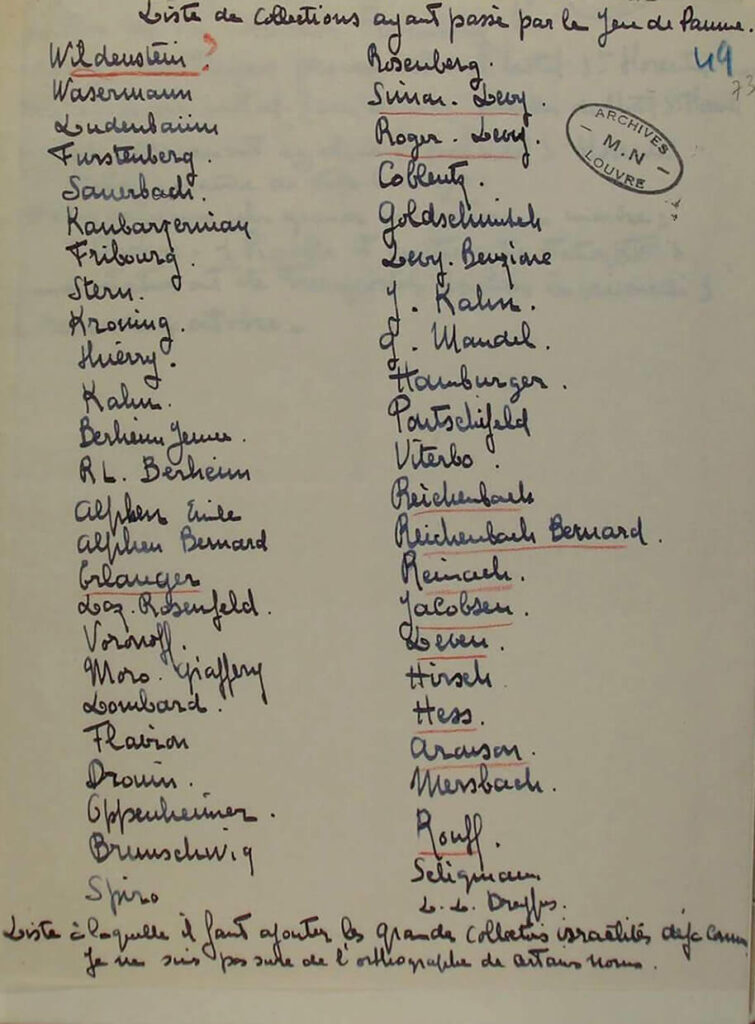

Page from Rose Valland’s wartime notes, Archives Nationales, Paris, France. Christie’s.

Facing the Danger

Working inside the Jeu de Paume came with constant risks. Rose Valland was accused of sabotage, theft, and even of signaling the enemy when a skylight illuminated a blacked-out Paris. The most distressing charges were related to missing artworks. Valland had to endure harsh interrogations by both the Gestapo and the military police. Despite repeated orders not to return, she always found a way back. Her role supervising building staff was her reason to stay.

All these incidents, which were multiplying, caused me constant apprehension and worry. In fact, such feelings overwhelmed me as soon as I was in front of the doors to the Jeu de Paume.

The Art Front: The Defense of French Collections 1939–1945.

She was caught only once, decoding shipping addresses, but managed to talk her way out. Still, the Nazis grew suspicious. She refused to sign the Nazi gag order, and wouldn’t let her colleagues sign it either, deepening their distrust. At one point, she learned they planned to send her to Germany, and kill her. Still, she stayed. With support from French staff, Valland held her post. Her secret reports from inside the museum remained French Resistance’s only source of intelligence on Nazi looting.

The Tragedy of Modern Art

Among the many looted works, some didn’t fit Nazi ideals and were labeled Entartete Kunst (degenerate art). Hidden in what Rose Valland called “the chamber of horrors,” these pieces were officially despised but secretly valued. Hitler himself approved the selective “salvaging” of some, not for admiration, but to help fund the war effort. Between 1941 and 1943, the Nazis orchestrated at least 28 exchanges, documented by Valland, trading “degenerate” pieces for more traditional works. Others weren’t so lucky and were smashed and burned in the museum courtyard.

Photograph of the Martyr’s Room, taken at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris, 1940. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

The Last Convoy

The Allied landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944, marked the beginning of the end. But for Rose Valland, it marked the most dangerous phase of her mission. As Nazi defeat loomed, would they destroy the looted art? Or impose threats toward her?

On August 1, 148 crates were sent from the Jeu de Paume to a nearby train station. A convoy was being prepared to transport these treasures to Germany. Five railcars were sealed, but the train wasn’t yet full, dozens more, filled with looted furniture, were still being loaded in a process that dragged on for ten days. Valland saw her chance. She alerted Jacques Jaujard, who would plan to intercept the train with the French rail company. The numbers of the train cars Valland recorded served as essential evidence, allowing the shipment to be tracked.

Rose Valland, Edith Standen, and colleagues supervising the loading of recovered artworks. Christie’s.

Mechanical issues bought them time. The train was delayed for 2 days in Le Bourget. Just as it was about to depart, a detachment from General Leclerc’s division intercepted the convoy. Against all odds, the entire shipment was recovered. One month after it had left the Jeu de Paume, Rose Valland proudly escorted the crates back with all the artworks remaining intact.

This was a modest triumph, a stepping stone on the path to recovering all the looted works of art, my action regarding the ERR had not been useless.

The Art Front: The Defense of French Collections 1939–1945.

The Liberation of Paris

As the Allies approached Paris, protecting the remaining artworks became paramount. When the uprising began, German patrols watched the Jeu de Paume closely to guard the many original paintings still hidden in the basement. German troops soon fortified the museum, turning it into a military outpost. Bu the final assault came even more swiftly. Within hours, the Germans surrendered.

But Valland stayed to defend the collections. Accused of hiding enemy soldiers, she was forced to lead a search at gunpoint. Nothing was found. Recognizing her commitment, soldiers helped secure the site. No paintings were lost. Thanks to her courage, the Jeu de Paume survived the war.

Valland and the Monuments Men

The arrival of the Monuments Men brought new uncertainty. Rose Valland was cautious. Could the Americans be trusted? If she shared what she knew, would they return the stolen art, or keep it?

Her doubts faded quickly. In November 1944, the recently created French Commission for Art Recovery named her secretary. She led inspections of former Nazi depots, joined by Lieutenant James Rorimer. After working closely with him, Valland came to trust his mission. When he was sent to Bavaria with the Seventh Army, she handed him her most valuable resource: her full archive on Nazi looting.

Monuments Man Captain Walter I. Farmer with Monuments Women Captain Rose Valland and Captain Edith A. Standen, private collection. Courtesy of Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

Beyond the Frontlines

By early 1945, it became clear that Rose Valland needed to follow the Allies into Nazi Germany. On May 4, she was commissioned as a lieutenant and Fine Arts officer in the French First Army. Once in Germany, her knowledge proved invaluable. She tracked down former ERR officials, including Dr. Schiedlausky, who confirmed the accuracy of her list of Nazi depots and helped complete it with details on their contents. This led to the discovery that many works, including the famed Ghent Altarpiece, were moved to Altaussee, Austria, in the final months of the war.

Ghent Altarpiece at Altaussee, c. 1945, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Valland stayed in Germany for eight years, helping recover and identify looted art. She got promoted to captain and worked tirelessly. One would often see her in uniform, cigarette in hand, inspecting artworks and coordinating returns. And she continued her work until years after the war had stopped.

A Silent Legacy

After returning from Germany in March 1953, Rose Valland expanded her search for missing artworks. She was honored by France, the United States, and Germany. Yet the recognition that meant the most came in 1952, when, after twenty years of service, she was finally named curator by the National Museums of France. Still, Rose Valland’s name remained relatively unknown in her own country for decades. Perhaps it was because she didn’t come from the elite circles of the art world. Or maybe, in postwar France, many simply preferred not to look back.

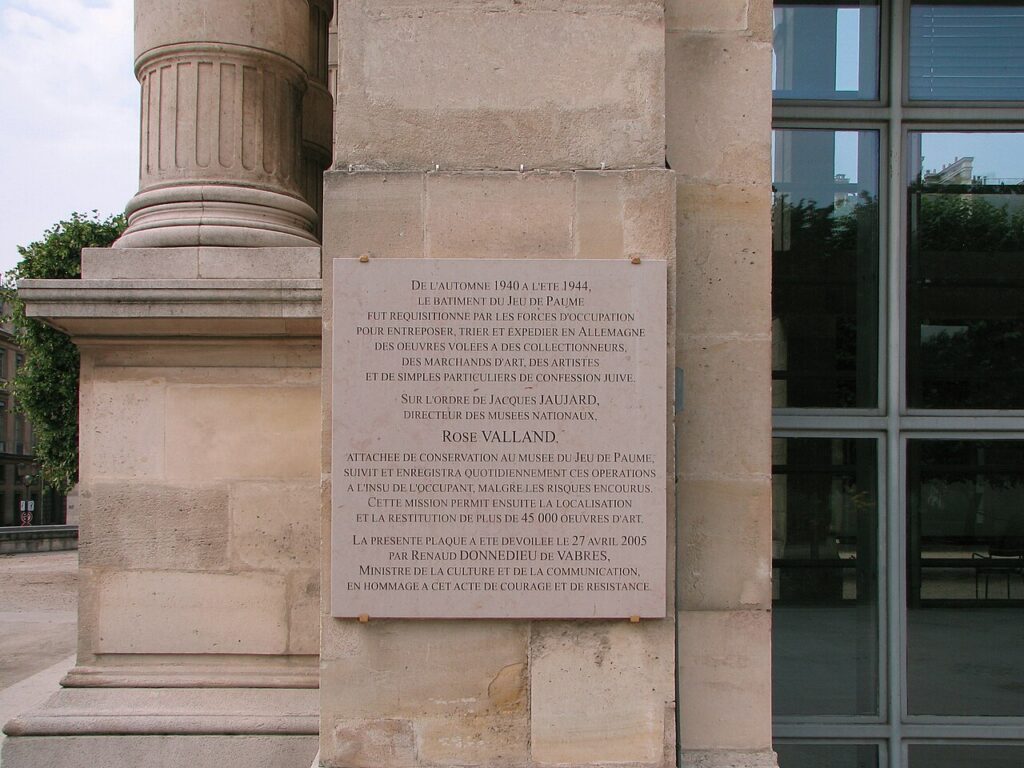

Commemorative plate on the wall of the Jeu de Paume, Paris, France. Photograph by TCY via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

In 1961, Rose Valland published her memoir, Le Front de l’Art, a firsthand account of her mission inside the Jeu de Paume. Just a few years later, her story caught Hollywood’s attention. In 1964, her story loosely inspired The Train (1964), a Hollywood film starring Burt Lancaster. Decades later, she reached new audiences through George Clooney’s The Monuments Men (2014), based on Robert Edsel’s book.

The Art of Memory

Her legacy lived on not only in the works she helped save, but in the admiration of those who understood the scale of her achievement. Fellow Monuments Men and Women described her as indispensable. Her knowledge, courage, and unwavering commitment made the recovery of stolen art possible on a scale that would have been unthinkable without her.

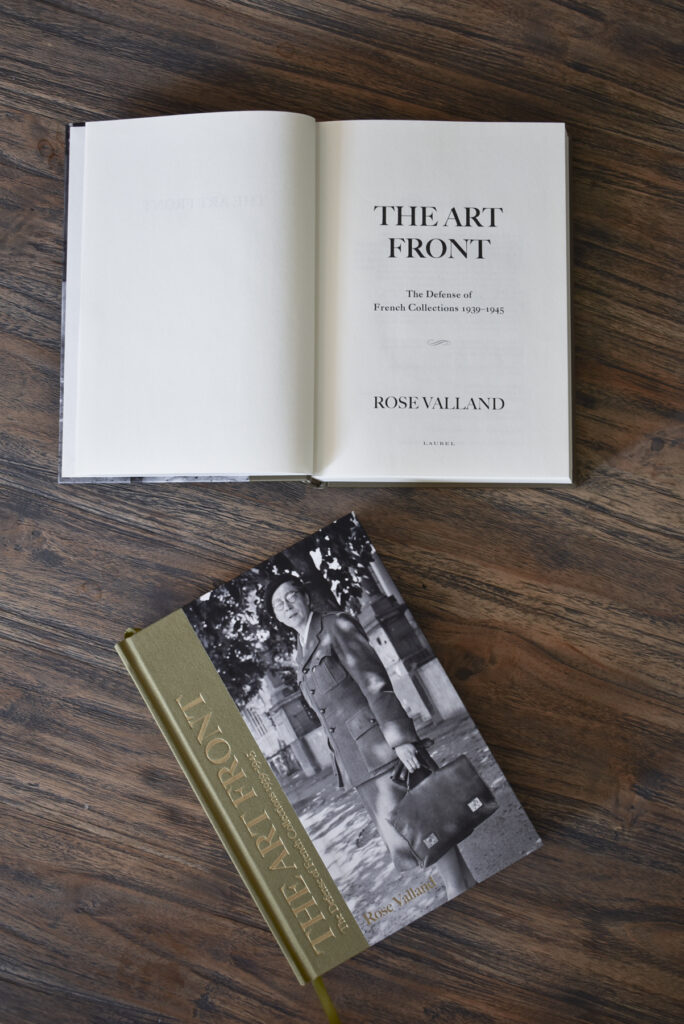

The new English translation of Rose Valland’s The Art Front. Courtesy of Monuments Men and Women Foundation.

With the first English translation of The Art Front, published by the Monuments Men and Women Foundation, Rose Valland’s voice finally reaches new audiences. As Anna Bottinelli, President of the Foundation, explains: “Rose Valland’s incomparable courage and dedication had to be known, in her own words, and accessible to readers worldwide. Translating her complex and deeply nuanced accounts of the wartime years was a difficult undertaking, one that had not been attempted before. Since its release, the response has been deeply rewarding, scholars recognize it as an irreplaceable primary source, while non-experts are deeply moved by her legacy. That her quiet bravery still resonates so strongly today underscores both the significance of this project and the enduring importance of safeguarding cultural heritage.”

Thus, her story is no longer confined to footnotes or archives, it stands as a powerful reminder of the role individuals can play in defending what defines us. Her courage wasn’t loud. It was revealed in small, steady acts of resistance, the kind that quietly shape history.