Art History 101: Color Theory

Color theory has played a central role in art throughout history, shaping how viewers respond to images even before they consciously think about the...

Jimena Aullet 12 January 2026

10 November 2025 min Read

As one of the most enduring symbols in world mythology, the sphinx embodies a fascination with mystery, power, and transformation. From its origins in ancient Egypt to its reimagining in Greek legend and beyond, the creature’s form and meaning have continually evolved across time and culture.

The mythological creature originated in ancient Egypt around 2500 BCE, with the Great Sphinx of Giza recognized as its earliest known depiction. The sphinx later became part of the Greek myth of Oedipus, circulating in oral tradition by the 8th century BCE, with early literary allusions in Homer’s Odyssey, and most famously in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, first performed around 429 BCE. Throughout centuries, the sphinx has continued to evolve across cultures, reimagined in diverse forms and meanings in art and material culture.

As both protector and destroyer, enigma and muse, and seducer and liberator, the sphinx remains a potent reflection of shifting societal ideals and artistic imagination. The transformative symbolism associated with the sphinx reflects humanity’s shifting values, fears, and aspirations, evolving from its medieval Christian depiction as a demonic figure to its 19th-century reinvention as the alluring and dangerous femme fatale, and continuing to inspire modern interpretations in literature, art, and popular culture.

Great Sphinx of Tanis, c. 2550 BCE, Louvre, Paris, France. Photograph by Shonagon via Wikimedia Commons (CC0).

The iconography of the sphinx originated in Ancient Egypt (c. 3150 BCE—30 BCE). Depictions typically bore the head of a pharaoh with the body of a lion, reflecting rulers’ possession of bestial strength and bravery, yet with the intellect and wisdom of a human. Unlike later depictions, sphinxes were often depicted as male and associated with authority, protection from evil, and guardianship.

The Great Sphinx of Giza, c. 2575–c. 2465 BCE. © Ron Gatepain/Brittanica.

The Great Sphinx of Giza and the Louvre monument reflect these themes in their gargantuan size, symmetrical proportions, dignified expression, and commanding presence. The placement of the sphinx guarding temple entrances serves as a connection between the earthly realm and divine power, emphasizing its symbolic link to the goddess Ma’at, bearer of truth, order, harmony, morality, and justice, and the god Ra, the creator of the universe and guardian of humankind.

Sphinx, Attic red-figure pyxis, 5th century BCE, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France. Photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.5).

In ancient Greek tradition (c. 800 BCE—146 BCE), the sphinx represented a more sinister figure. Depicted with the head of a woman, the body of a lion, and the wings of a bird, it was seen as a cunning and merciless creature. Reflecting the culture of the civilization, the Greek sphinx embodies a dynamic, tumultuous, and often fatal journey toward truth, intertwined with the fragility of life. In contrast, the Egyptian sphinx is solid, static, and eternal.

According to Greek myth, the sphinx posed riddles to travelers and devoured those who could not answer correctly. The most famous iteration of this mythological creature appears in the story of Oedipus, who correctly answers the sphinx’s riddle, causing it to throw itself from a cliff in a state of self-destruction.

Sphinx of Naxos, 560 BCE, Delphi Archaeological Museum, Delphi, Greece. Photograph by Ricardo André Frantz via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

For the Greeks, the sphinx symbolized divine punishment and the enigmatic forces of fate. While Oedipus is anointed the King of Thebes following his conquest of the sphinx, his eventual downfall emphasizes the inescapability of fate and the tragic consequences of human ignorance, hubris, and pride. Greek sphinxes, though often depicted in a seated, regal posture, also guarding temple entrances, had connotations of warning, mystery, and trickery rather than benevolent protection.

Illumination in Livre du Tresor des hystoires des plus notables et memorables hystoires qui ont esté depuis le commencement de la creacion du monde jusques au temps du pape Jehan XXII (Ms 278), f. 35v, 1375–1400, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, France.

The sphinx reappears in the bestiaries of medieval art and folklore (5th to late 15th century), reinterpreted with a knight heroically defeating a beastly creature, as opposed to the sphinx’s self-imposed demise.

The sphinx acted as a symbol of paganism, demonic forces, and deception, reflecting the Christianization of the myth and anxieties about damnation and heresy. Its riddling nature and hybrid form made it a popular figure in allegorical texts, where it embodied temptation and evil. Manuscripts adopted the imagery of the sphinx to symbolize the triumph of Christian virtue over pagan sin, reflecting broader cultural beliefs.

Illumination from Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César, second redaction, British Library—Royal 20 D I, fol. 2v, c. 1330–1340, British Library, London, UK.

The sphinx is depicted with the head and torso of a seemingly ordinary woman, usually in a fearful or defensive position, rather than regal, adorned, or imposing. The defeat of an untrustworthy and malicious woman can be interpreted as the reinforcement of patriarchal Christian values, denouncing the seductive powers of women. The temptation was viewed as sin, which men ought to conquer. This provides a reading of the medieval adaptation of the sphinx as a recognizably human woman, in an age of religious revision and male dominance.

Oedipus and the Sphinx, manuscript of Histoire ancienne jusqu’à César (Ms 562), f. 67v, c. 1260–1270, Bibliothèque municipale de Dijon, Dijon, France. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

As a deeper cultural analysis, suspicion of women and their association with mysticism, beastliness, and dark forces, is brought into realization with the witch trials of the 15th century.

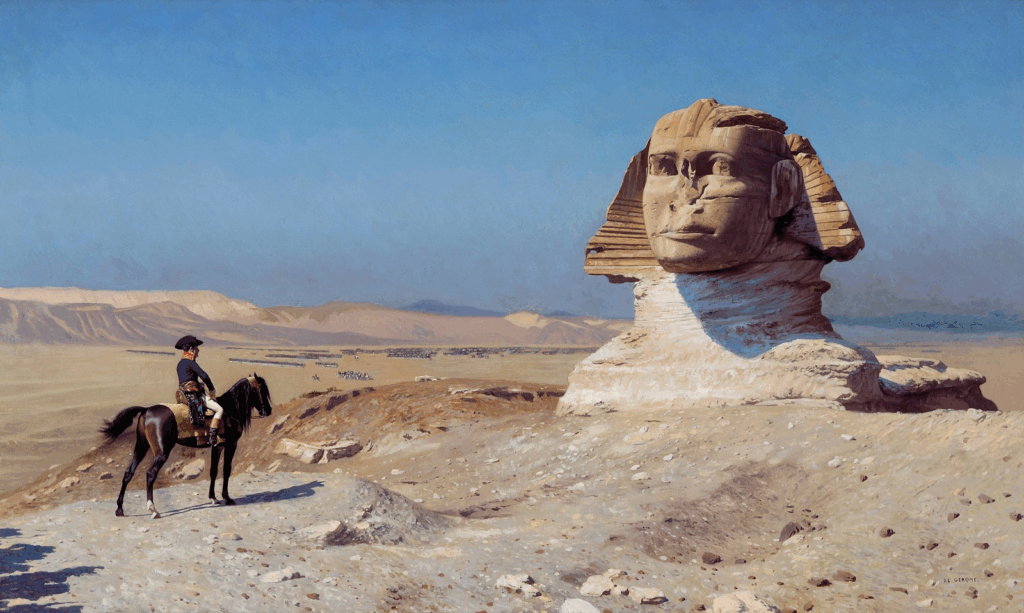

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, 1886, Hearst Castle, San Simeon, CA, USA.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (c. 1867–1868) explores the tension between European colonialism, then justified as a civilizing and progressive mission, and the monumental legacy of ancient civilizations. The painting contemplates the enigmatic nature of time, conveyed through its stillness and the sphinx’s solid, immovable, yet weathered presence. Bonaparte, embodying societal movement, ambition, and turbulence, is rendered diminutive in comparison to the enduring permanence of history.

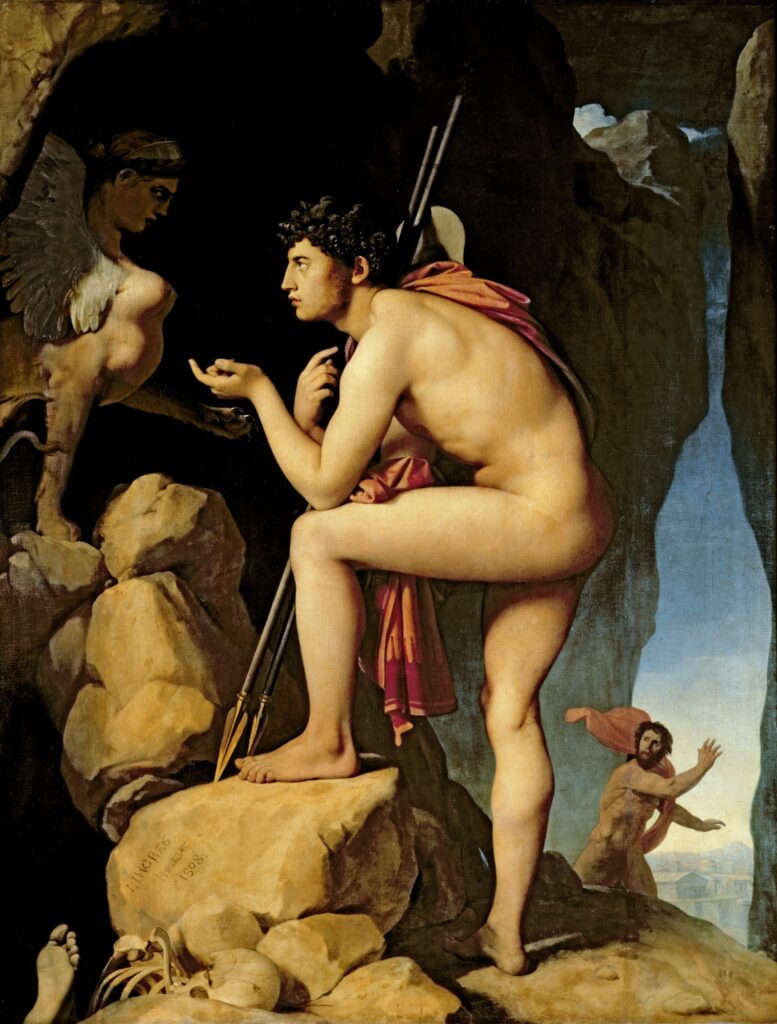

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Oedipus and the Sphinx, c. 1826, National Gallery, London, UK.

Taking inspiration from the Greek myth, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Oedipus and the Sphinx (1808–1827) depicts the sphinx as small, sexualized, and static. Seemingly unafraid of it, Oedipus dominates the composition. He is positioned, leaning in close to it daringly and inquisitively, illuminated by the light, whilst the sphinx remains partly hidden in the darkness of the cave, its chest being the most visible part of its body. The bones piled on the floor indicate that despite the sphinx’s alluring appearance, it is lethal.

19th-century art and ideology explicitly developed the symbolic significance of the feminine sphinx. Within this period, many Greek mythological figures were incorporated into popular art movements. This included Circe, associated with animal kinship and known for turning men into pigs, Medea, known for murdering her adulterous husband and children, eradicating his legacy, and Medusa, a monstrous woman known for turning men into stone.

These recurring themes formed the trope of the femme fatale, which characterized sexualized women who tempted, manipulated, and corrupted men with their dangerous sensuality, leading to their moral demise and threatening their dominance.

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Gustave Moreau’s Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864) bears similarities to Ingres’s portrayal, as Oedipus and the sphinx engage in an arresting and daring gaze. They seemingly challenge one another in a sexualized power struggle in which Oedipus fearlessly confronts the small-framed sphinx whom he looks down upon.

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Wanderer (The Equality Before the Face of Death), 1888, Musée de la Cour d’Or, Metz, France.

Juxtaposing this, Moreau’s Oedipus and the Wanderer (1888) emphasizes the dangerous and intimidating nature of the sphinx, whose large, illuminated wings dominate the composition. Elevated and surrounded by darkness, a cowering figure, and dead bodies, this interpretation alludes to an alternative dynamic in which men give way to the creature’s power. In this interpretation, the sphinx represents an explicit threat, its prominent chest reminding the viewer that the threat is gendered and sexualized.

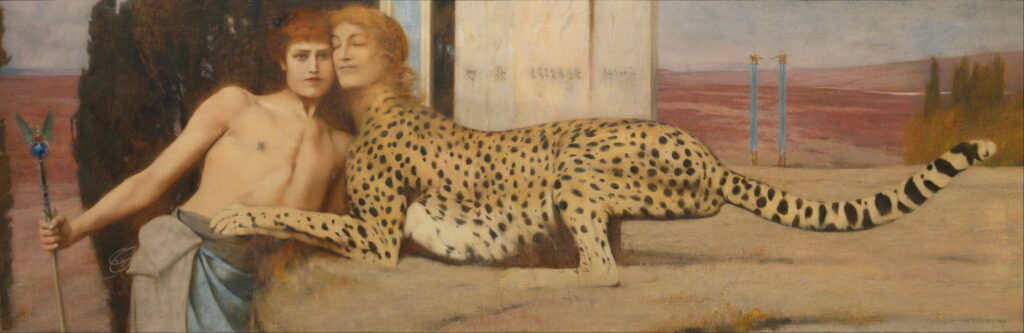

Fernand Khnopff, Caress of the Sphinx, 1896, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium.

Fernand Khnopff extended the imagery of the sphinx as a femme fatale, depicting them physically interacting with men, seemingly as an adoring pet, subserviently rubbing their faces against them. Khnopff, aligning with many symbolist artists, adopted the misogynist idea of the spiritual, intellectual male, juxtaposing the carnal and bestial woman. The androgyne, depicted in Caress of the Sphinx (1896), appears as a feminine man, understood as the highest ideal by incorporating the beauty of a woman with the intellect and strength of a man.

Fernand Khnopff, An Angel, 1889, Städel, Frankfurt, Germany.

Khnopff clearly delineates the distinction between the spiritually attuned androgyne and the bestial, untamed, primordial woman through the embodiment of a sphinx. An Angel (1889) further demonstrates the taming of a sphinx, representing the taming of female carnality.

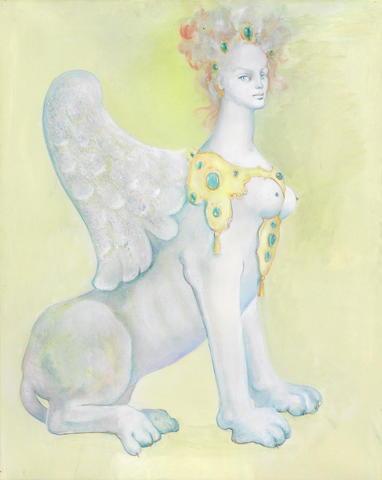

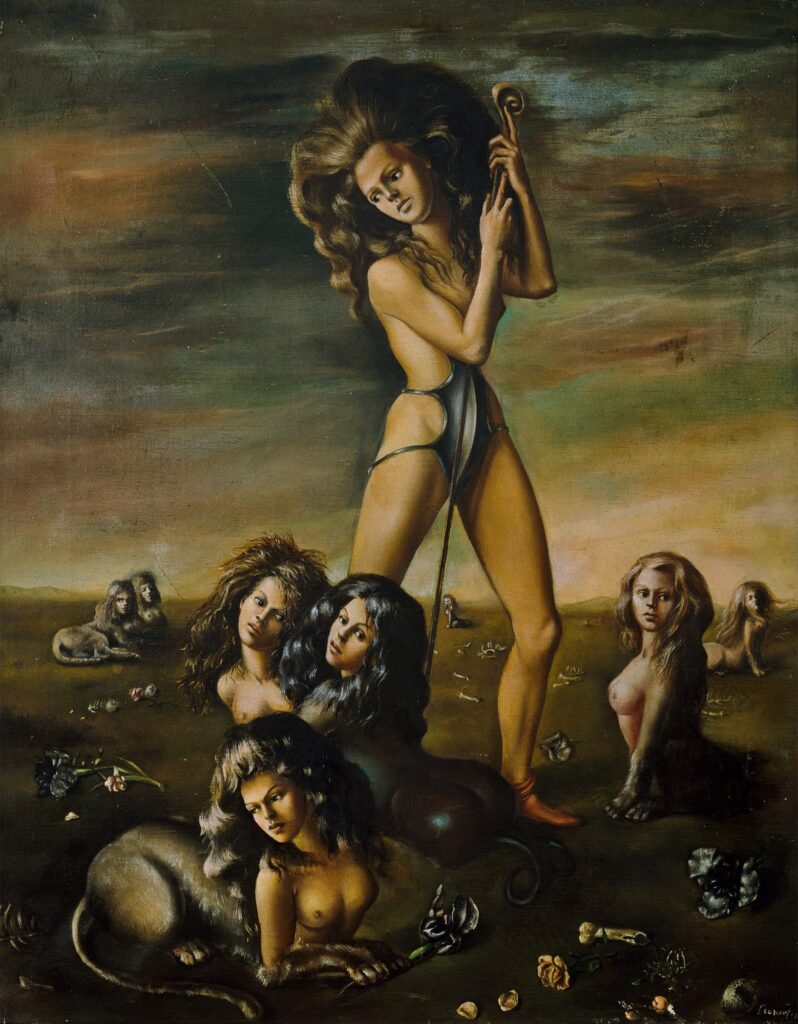

Leonor Fini, Sphinx Ariane, 1973. Bonhams.

Leonor Fini, along with other women Surrealists, reappropriated the figure of the sphinx in defiance of the 19th century’s dominant Symbolism, which cast it as an emblem of the dangers of feminine seduction, as well as the inferiority of women. Fini’s sphinxes are otherworldly, powerful, intimidating, and enigmatic. By excluding male figures, she overturns the Oedipal myth where the sphinx is destroyed by male challengers. Instead, Fini reclaims it as autonomous and matriarchal.

Leonor Fini, The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes, 1941, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, Italy.

In The Shepherdess of the Sphinxes (1941), Fini presents a commanding figure presiding over an untamed sisterhood of sphinxes. The metal breastplate can be read as evoking a chastity belt, reflecting both the suppression of female sexuality in earlier interpretations of the sphinx and its reconfiguration here as a symbol of power, with its staff symbolizing sexual autonomy. The half-woman, half-lion sphinxes appear satiated and confident, seemingly in the aftermath of a feast. Reinforcing their intimidating unity, bones and eggshells are scattered across a withering landscape of death and degeneration, yet these motifs are juxtaposed with the transformative connotations of the hybrid women.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!