Shiva Nataraja – The Hindu Lord of the Dance. Iconography and Symbolism

Nataraja, the manifestation of the Hindu god Shiva as the Lord of the Dance, holds a profound significance in Hindu mythology and symbolism. Depicted...

Maya M. Tola 3 June 2024

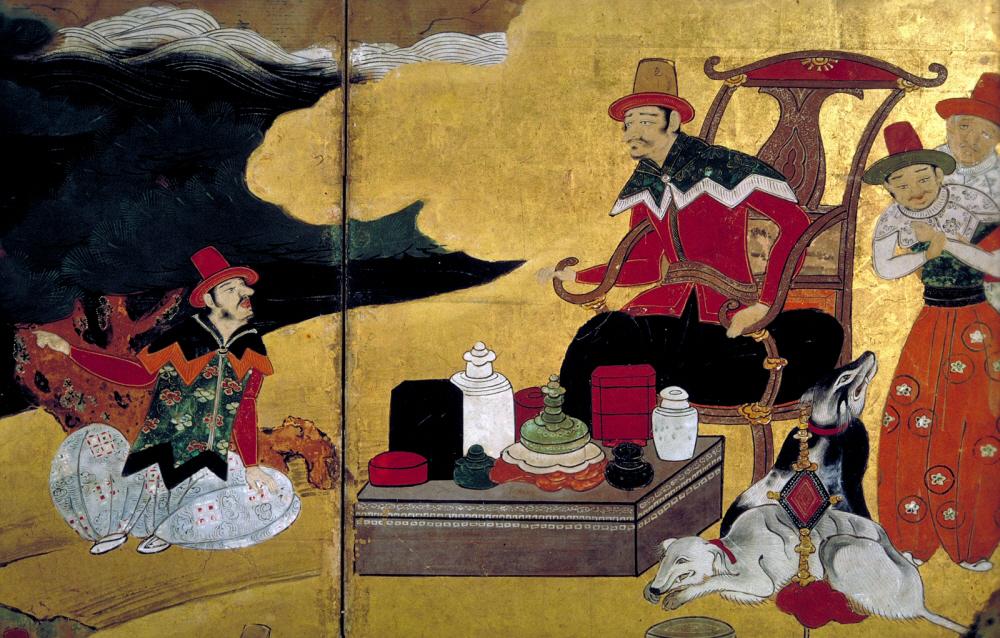

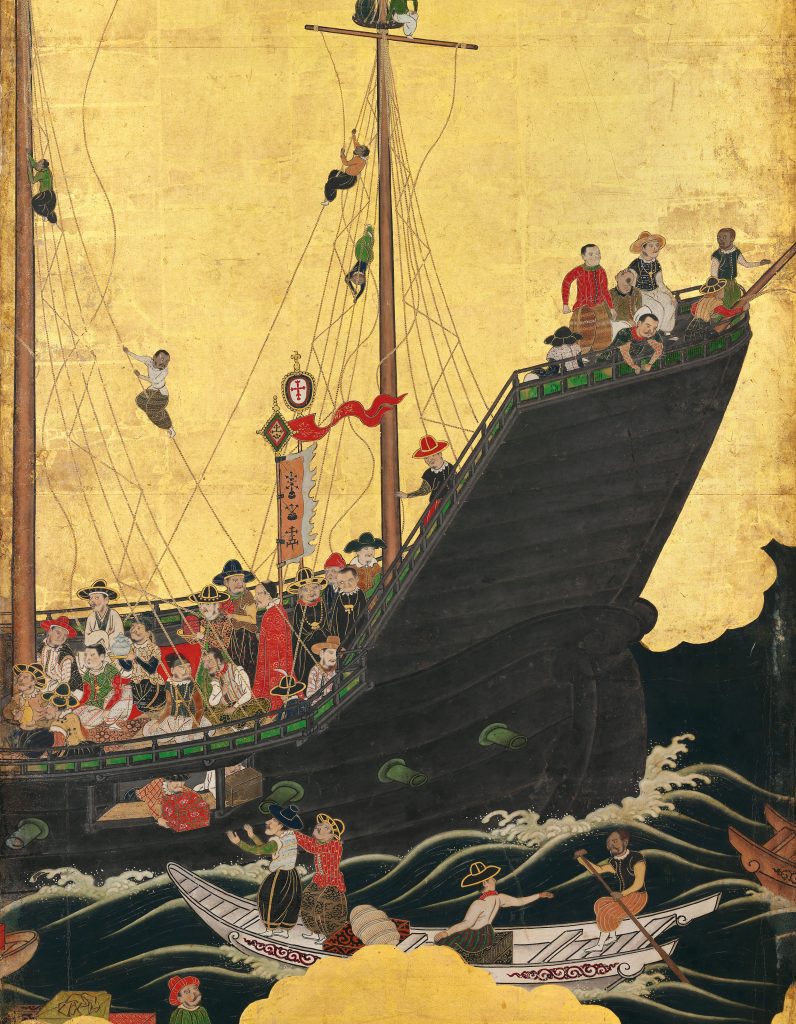

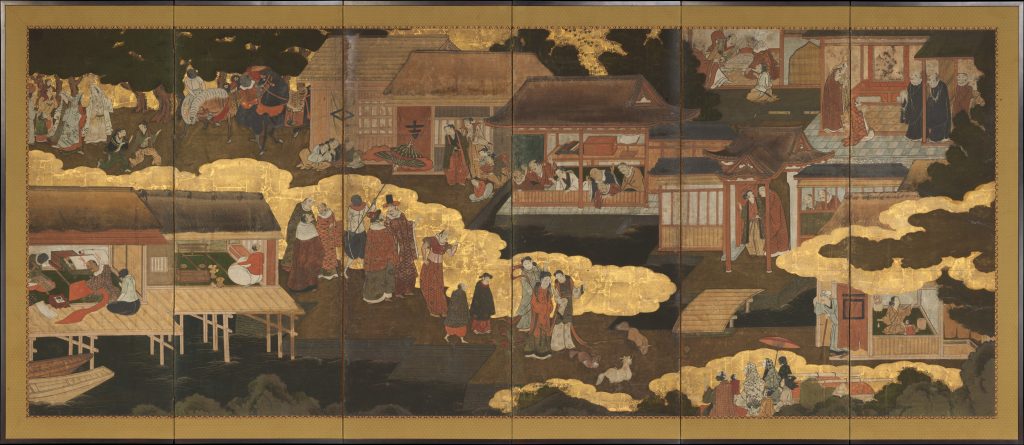

Masterfully crafted into hinged leaves and enclosed within a lacquer frame, the Japanese Namban folding screens or the Namban byōbu contain a fascinating visual record of the arrival of Portuguese ships at the island of Kyushu in 1543. The incidental visit from these exotic foreigners was the primary theme of these artworks. These screens are the culmination of Japanese curiosity and bemusement as well as their considerable apprehension at the unexpected arrival.

Byōbu or folding screens have ancient Chinese roots dating back to the Han Dynasty in the 8th Century. The tradition spread across the Far East and developed independently in Japan. Byōbu are often comprised of a set of panels that are decorated with artwork and calligraphy and they may even serve practical purposes as room dividers.

Namban art refers to a broad area of work, a testament to the first cultural exchange between Southern Europeans and the Japanese in the 16th century. It covers a wide variety of art produced in both Japanese and Western styles. The Namban screens are but one of its manifestations that provide a vivid, albeit not entirely visually accurate historical record that encapsulates the Japanese reaction to their first foreign visitors.

Namban or Nanban is a Sino-Japanese word that translates into “southern barbarians”. This rather harsh term was used to refer to the merchants and travelers who docked on Chinese ports from the South, particularly referring to the South Asian and Southeast Asian merchants and traders. This term spread to Japan and evolved to include the Portuguese who arrived from the Southern sea route.

In 1543 a terrible storm caused a Chinese ship to drift onto Tanegashima, a small Japanese island near Kyushu. This ship happened to be carrying three Portuguese travelers, Japan’s first-ever European tourists. Thereafter, several more ships followed and there was an influx of merchants and missionaries eager to bring their wares and their faith to this newly discovered market. Merchants imported precious and semi-precious metals, textiles, lacquer, etc. to Japan. Francis Xavier, the notable Jesuit stationed in Goa, became the first to introduce Christianity to Japan in 1551.

A typical composition of these screens portrays the Japanese shore on the right and the ocean on the left. The screens depict the relatively tall foreigners of different races in exotic clothing. These are lively depictions of the hustle and bustle of a busy port. The screens go into great detail including the arrival of foreign ships, the loading, and unloading of cargo, and foreign warriors. Locals feature on the screens too, often inspecting their guests.

Also included in these artworks are the newly introduced Christian icons, such as churches and priests. Thus indicating that the missionaries’ trips to Japan bore fruit despite the eventual ban on Christianity in 1641.

Several of the Namban byōbu were painted by well-known artists of the elite Kano-school, known for their great precision and careful attention to detail. It is, therefore, interesting to note that the representations in these artworks were sometimes implausible. The ships appear to be imagined or adapted from European artworks and not the typical ships that the Portuguese employed along this route. Furthermore, the female Europeans depicted were dressed in Chinese rather than European garb. It has been theorized that this was likely due to the fact that these artists may have never actually seen a foreign ship or European female with their own eyes. Although trade flourished, the foreign visitors were restricted to certain areas of a designated port and were constantly supervised during their stay in Japan. Meanwhile women were not permitted to disembark onto Japanese ports at all and stayed on the merchant’s ships during their stop. These policies were implemented to discourage any notion of long-term settlement by these southern barbarians!

The Portuguese dominated the European-Japanese trade industry for nearly a century until an eventual decline after the Japanese ban on Christianity in 1641. Once Portuguese trade came to an end, Namban arts declined as well. It is estimated that 60 to 80 Namban byōbu are in existence today, leaving behind an artistic tribute to the unexpected initiation of the world’s first trade relationship between Japan and Europe.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!