Buddhism’s Arrival

Buddhism arrived in China from India around the 1st century BCE. However, it did not achieve widespread popularity for another three centuries until around 220 CE with the political collapse of the Han Dynasty. Buddhism gained popularity because it addressed the tumultuous period of instability and suffering with the promise of salvation and enlightenment.

Dated Works

As a philosophical religion, Buddhism appealed to a wide range of socioeconomic devotees. Devotional objects representing the Buddha and bodhisattvas quickly entered many households, ranging from rural peasants to the urban elites.

For almost 2,000 years, Chinese artists have been creating countless Buddhist works, including images of the Buddha. However, the chronology of Chinese Buddhist art is sometimes difficult to determine due to the lack of dated works. Nevertheless, several important works are dated and help establish a timeline. Buddha dated 338 is one such work. It is a masterpiece of both Buddhist art and Chinese art with deep historical significance.

Chinese Buddhism

The sculpture was created in 338 CE in Hebei Province during the Later Zhao dynasty (319–351). It is the earliest known dated Chinese Buddha statue; as such, it sets the official dated beginning of a long tradition of Chinese Buddhist sculpture.

Composition

Buddha dated 338 is a figural seated statue of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. It measures 16 in. tall (40 cm) from the topknot down to the rectangular base. It was created from a base of leaded bronze covered with a thin layer of gold. An early Chinese Buddhist text stated that the Buddha was golden and radiated light. Therefore, gilt bronze was a natural choice as a medium. The mercury gilding supplied the reflective radiance while the bronze prevented prohibitively expensive solid-gold manufacturing.

Ushnisha

One of the most identifiable markers of the Buddha is his ushnisha, which is a protuberance on top of his head. Many Chinese Buddhist texts say that it represents the “crown” of the Buddha for achieving Enlightenment as the King of the Dharma. Earlier statues from India depict the ushnisha as a fleshy knob. Later Chinese interpretations, such as this Buddha, use a hair topknot which aligns closer to a Chinese aesthetic for a Chinese devotee.

Facial Ideals

As Buddhism spread across different countries and cultures, images of the Buddha adapted to local aesthetic tastes. The face of the Buddha conforms closely to Chinese ideals. The face is round with large, wide, almond-shaped eyes. It has strong eyebrows and a defined nose. Unlike Indian prototypes that frequently possessed a mustache, Chinese ideals preferred a clean-shaven and smiling face. Therefore, this Buddha statue has a more Chinese, smooth, and happy appearance.

Gandharan Robe

The robe of the Buddha drapes elegantly from his shoulders in concentric folds. The regularity and consistency of the folds create a harmonious pattern that implies balance and fluidity. It is not a naturalistic depiction of real-world fabric, but a supernatural or ethereal depiction of spiritual shrouding. This fabric style is heavily influenced by Gandhara, which was an ancient Indo-Aryan civilization in the area of northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. This vital trading partner was one of the early entry points of Buddhism into China, and with it, some of its aesthetic art influence.

Hand Gesture

The positioning of the Buddha’s hands has long played a vital role in the diffusion and interpretation of Buddhist art. In Buddha dated 338, the Buddha folds his hands across his stomach.

Some scholars believe that the artist misrepresented the dhyana mudra (meditation gesture), which normally presents the palms facing upward and the thumbs elevated and barely touching each other. These same scholars believe the artist was either misinformed or ignorant of Buddhist gestures since Buddhism was still fairly new to China.

However, other scholars believe this Buddha’s hand gesture is perfectly intentional. With his palms facing his body, and overlapping across his stomach, it creates the formal Chinese gesture of reverence. Therefore, like possessing a topknot and excluding a mustache, this Buddha is assimilating Chinese aesthetic and culture.

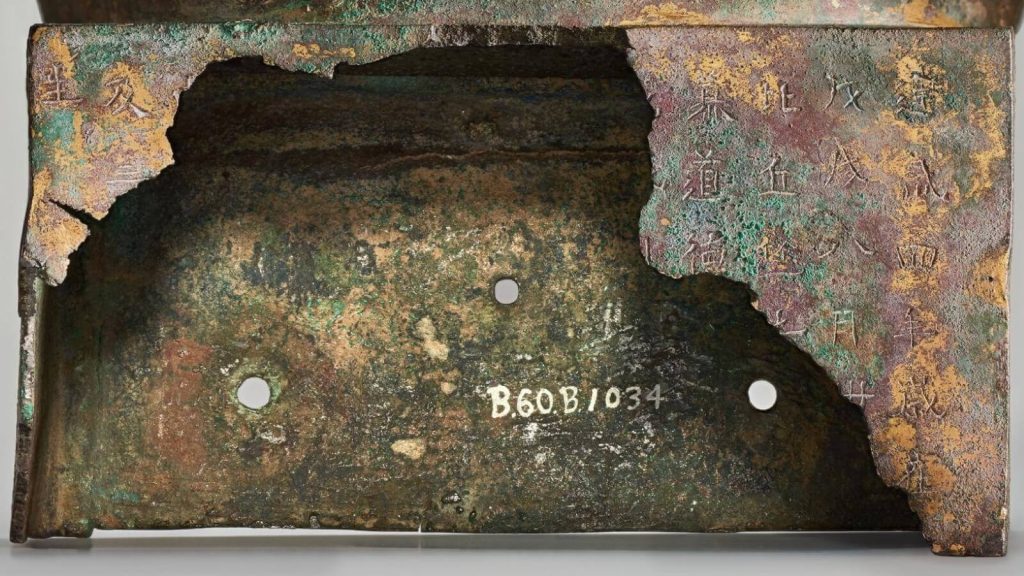

Base

The Buddha sits on a box-like rectangular base. It appears to be void of decoration, but it has three substantial holes in the front panel. Why are there holes in the base?

Missing attachments once adorned the front facade. Scholars believe that a pair of lion ornaments was inserted in the left and right holes, while a lotus motif filled the central hole. The lions represented regality, strength, and power. They also symbolized the Buddha’s teachings as they are frequently referred to as the “Lion’s Roar.” The lost lotus represented Enlightenment, and along with the lion, is one of Buddhism’s most powerful symbols.

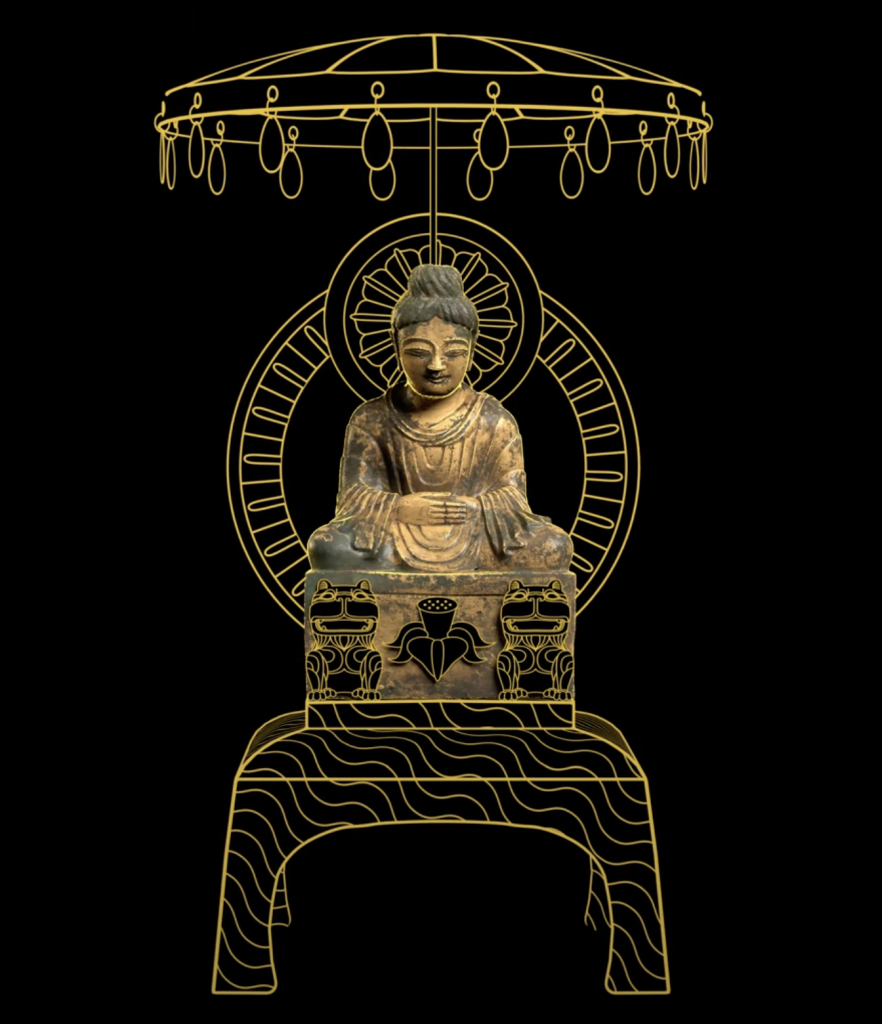

Reconstruction

At over 1,600 years old, this figure of Buddha lacks many of its original features that have perished over time. On top of the topknot is a deep shaft that once allowed an inserted canopy to rise from the top of the head. This canopy would have represented royalty and symbolized auspiciousness.