5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

With thousands of years of continuous history, China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations. It is also one of the most culturally unique nations. Throughout many centuries, Chinese artists depicted landscapes, animals, and beauties with attention to detail. Instead of using flat canvases, they mostly created paintings on hand scrolls. Some of these paintings are now in the hearts of more than a billion people. Explore the top 10 most famous Chinese paintings spanning about 1400 years. And, perhaps, some of these handscrolls could also win your heart.

First, let’s dive into the Luo River and find a nymph.

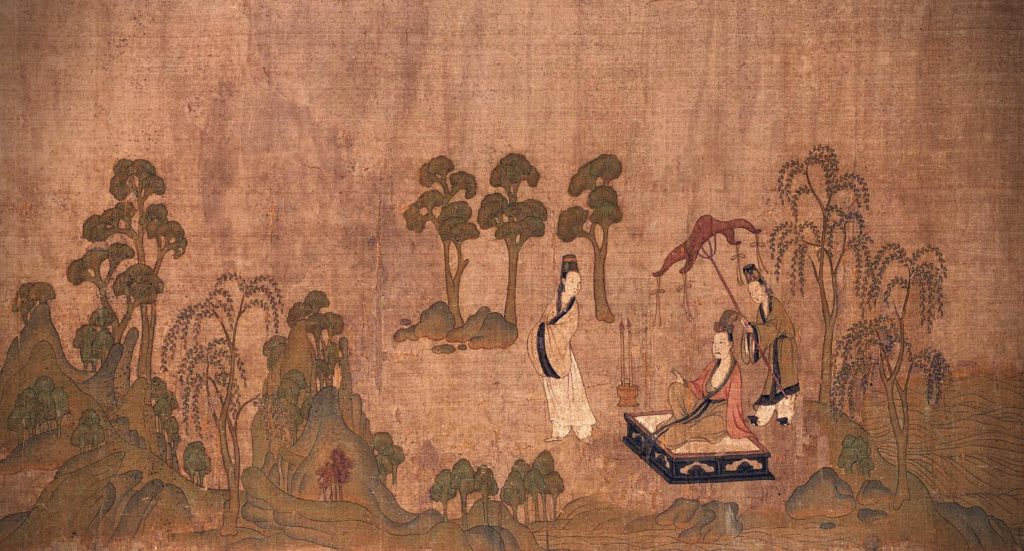

The legend has it that Cao Zhi (192-232), a prince of the state of Cao Wei, fell in love with the magistrate’s daughter. However, she married his brother, Cao Pi, and the prince became dejected. Later, he composed an emotional poem about the love between a goddess and a mortal. In the 4th century, Gu Kaizhi (ca. 344-ca. 406), a Chinese artist, was moved by the story and illustrated the poem.

Unfortunately, the original 4th-century painting was lost. However, artists made several copies of the Nymph of the Luo River, probably during the Song dynasty (960-1279). The painting is in the form of a long scroll, which describes the plot in sections. Therefore, as with all Chinese handscrolls, to understand their meaning, it is best to view them from right to left. Let’s unfold the scroll and find out about this beautiful story.

In the beginning, Cao Zhi travels with a group of attendants and has to cross the Luo River. Here, Gu Kaizhi gives full play to his artistic imagination. Through clever composition and the application of vivid colors, he depicts the meeting between Cao Zhi and the nymph, Fu Fei. She flows lightly and stops when she wants to go. Then, the prince finds out that Fu Fei is a nymph. Captivated by her charm, Cao falls in love with Fu Fei. In the poem, he praises the nymph’s beauty.

Gazing at her from afar,

She shines like the sun rising above the rosy mists of dawn;

Observing her close by,

She is as luminous as a lotus emerging from clear ripplets.Cao Zhi, Ode to the Nymph of the Luo River, 222. Translated by R.J. Cutter.

If you want to tell a person how beautiful they are, you can use this poem as a source of inspiration. As for the nymph, she is dignified, sometimes she wanders in the water, sometimes she flies in the clouds. Fu Fei is singing and dancing in the air, she and Cao Zhi see each other. Alas, the paths of gods and humans are different. The love between a mortal poet and a nymph does not last long. Thus, accompanied by flying fish and sea dragons with long antlers, Fu Fei bids Cao farewell, then vanishes. Cao is searching in vain for the nymph. Longing for her, he spends a sleepless night.

Cao Zhi’s poem is clearly a love story. However, it can also be interpreted as an allegory for his failed attempts to gain a position to serve the regime. Still, the poem speaks about the nature of love and reflects the brevity of life in a time of frequent war.

In many Chinese traditional paintings, nature is depicted prominently. However, because this handscroll narrates the story, the landscape serves as a mere stage for various scenes. Here, people and animals appear larger than simplified trees, clouds, and mountains. Moreover, birds and dragons, inhabiting the painting, make the atmosphere dreamlike. The monster with a dragon head and in the dressed-to-impress white pantaloon trousers seems to agree.

Furthermore, Gu Kaizhi depicts water as smooth, rippling, or swirling. These different representations reflect melancholy, excitement, or surprise. Although the monsters are running on the river, it looks as if they are soaring in the air. This approach enhances the atmosphere of the painting and makes it interesting and memorable. Now we can see why the Nymph of the Luo River is a masterpiece and a famous painting.

In the 7th century, Tibet admired the Tang dynasty of China. In 634, on an official state visit to China, Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo (569-ca. 649) fell in love with and pursued Princess Wencheng’s hand. He sent envoys and tributes to China but was refused. Consequently, Gampo’s army marched into China, burning cities until they reached Luoyang, where the Tang Army defeated the Tibetans.

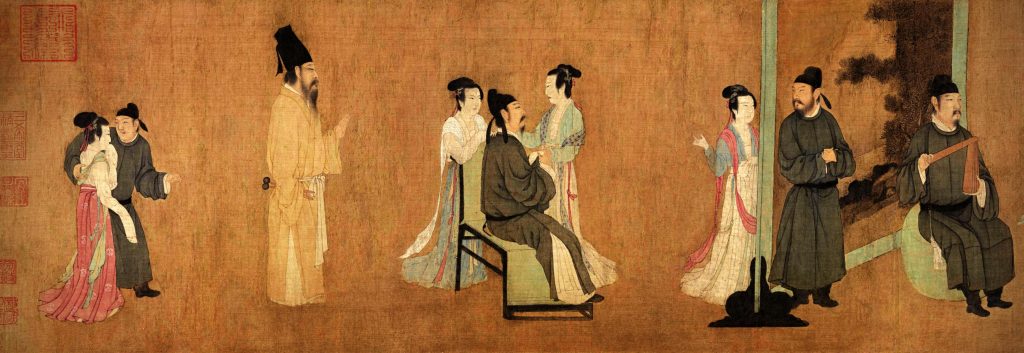

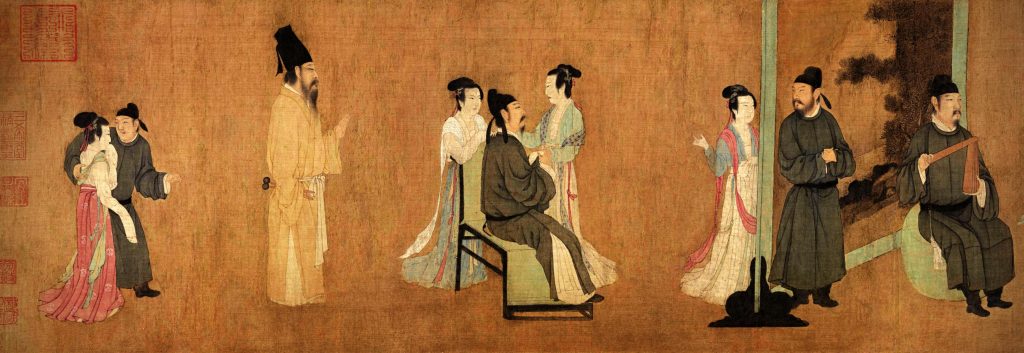

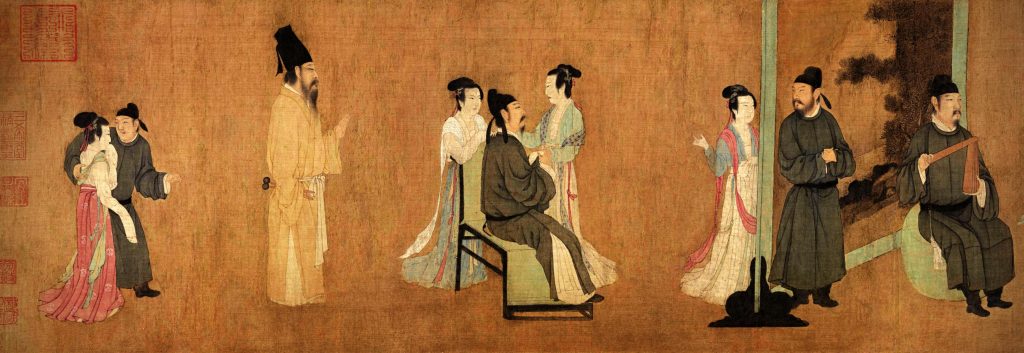

Nevertheless, Emperor Taizong (598–649) finally gave Gampo Princess Wencheng in marriage. Yan Liben (ca. 600–673), a Chinese artist, showed the encounter between the Tang dynasty and Tibet in his painting Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy. As with other early Chinese paintings, this scroll is probably a Song dynasty (960–1279) copy from the original. We can see the emperor in his casual attire sitting on his sedan.

On the left, one person in red is the official in the royal court. The fearful Tibetan envoy stands in the middle and holds the emperor in awe. The person farthest to the left is an interpreter. Emperor Taizong and the Tibetan minister represent two sides. Therefore, their different manners and physical appearances reinforce the dualism of the composition. These differences emphasize Taizong’s political superiority.

Yan Liben uses vivid colors to portray the scene. Moreover, he skillfully outlines the characters, making their expression lifelike. He also depicts the emperor and the Chinese official larger than the others to emphasize the status of these characters. Therefore, not only does this famous handscroll have historical significance but it also shows artistic achievement.

In 641, the Prime Minister of Tibet came to Chang’an to accompany the princess back to Tibet. The princess brought with her promises of trade agreements, maps on the Silk Road, and the dowry which contained not only gold but also fine furniture, silks, and porcelains. All in all, Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo had six consorts, four of them were native, and two were foreign. He is thought to be the first to bring Buddhism to the Tibetan people.

During the Tang dynasty (618–907), China had a prosperous economy and flourishing culture. In this period, the genre of “beautiful women painting” enjoyed popularity. Coming from a noble background, Zhou Fang (ca. 730–800), a Chinese artist, created artworks in this genre. His painting Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers illustrates the ideals of feminine beauty and the customs of the time.

In the Tang dynasty (618–907), a voluptuous body symbolized the ideal of feminine beauty. Therefore, Zhou Fang depicted the Chinese court ladies with round faces and plump figures. The ladies are dressed in long, loose-fitting gowns covered by transparent gauze. Their dresses are decorated with floral or geometric motifs. The ladies stand as though they are fashion models, but one of them is entertaining herself by teasing a cute dog.

Their eyebrows look like butterfly wings. They have slender eyes, full noses, and small mouths. Their hairstyle is done up in a high bun adorned with blossoms, such as peonies or lotuses. The ladies also have a fair complexion as a result of the application of white pigment to their skin. Although Zhou Fang portrays the ladies as works of art, this artificiality only enhances the ladies’ sensuality.

Holding a long-handled fan, the maidservant follows another palace lady. Although the maidservant stands in the foreground, the lady appears larger because of her higher status. She gazes at a red flower that she holds in her hand, ready to adorn her hair with it. A beautiful crane solemnly passes nearby.

By placing human figures and non-human images, the artist makes analogies between them. Non-human images enhance the delicacy of the ladies who are also fixtures of the imperial garden. They and the ladies keep each other company and share each other’s loneliness.

During the Festival of Flowers, courtiers adorned their hair with artificial flowers made of paper or silk. They held outdoor picnics to celebrate the revival of nature. The ladies admired the beauty of the flowers, but these blossoms also symbolized the fleeting nature of youth.

Zhou Fang not only excelled in portraying the fashion of the time. He also revealed the court ladies’ inner emotions through the subtle depiction of their facial expressions. Thus, showing the fashion of the time, this painting holds great significance in Chinese art. Nowadays, the Festival of Flowers is generally celebrated in March every year.

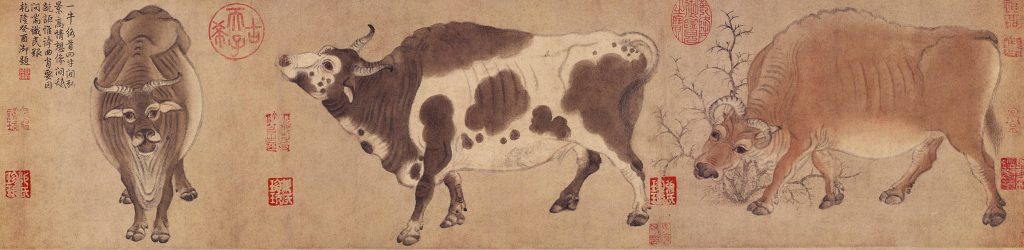

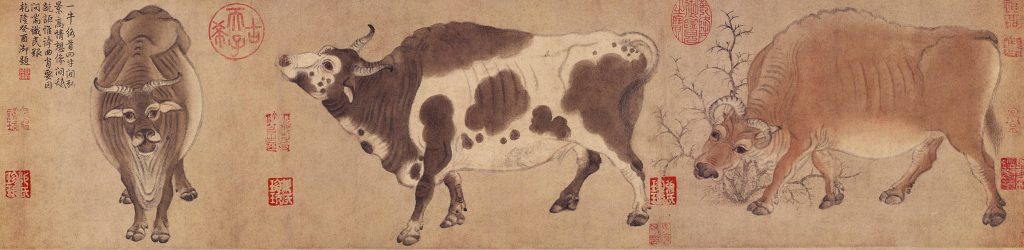

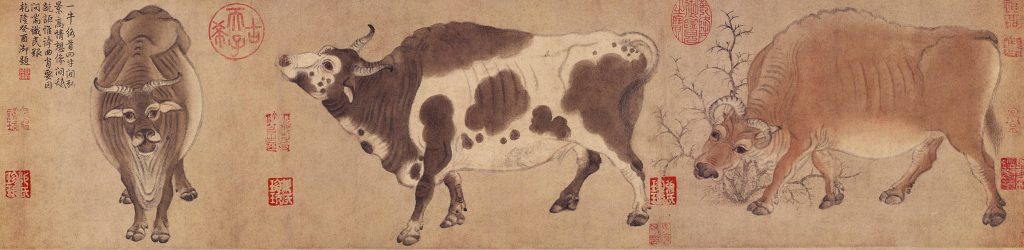

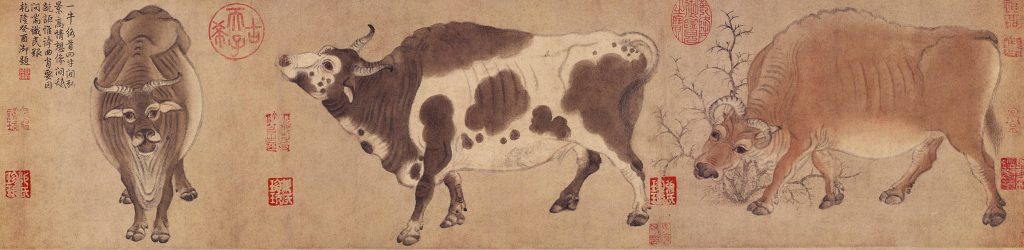

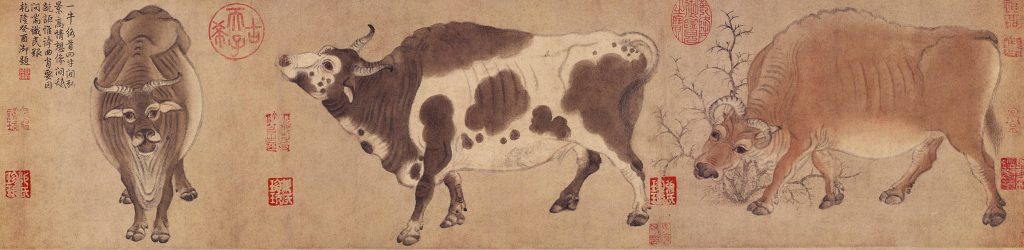

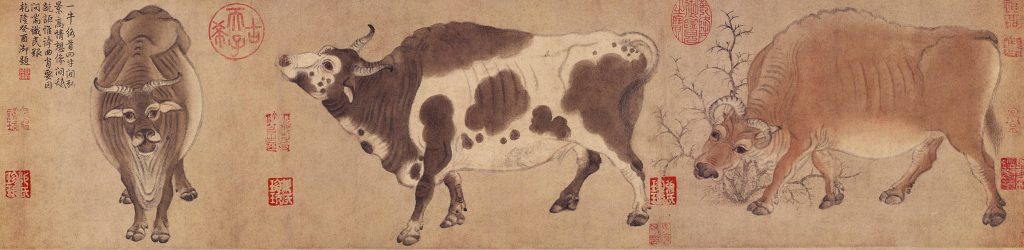

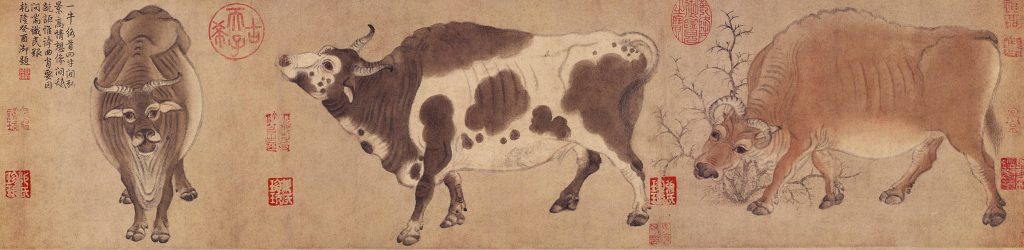

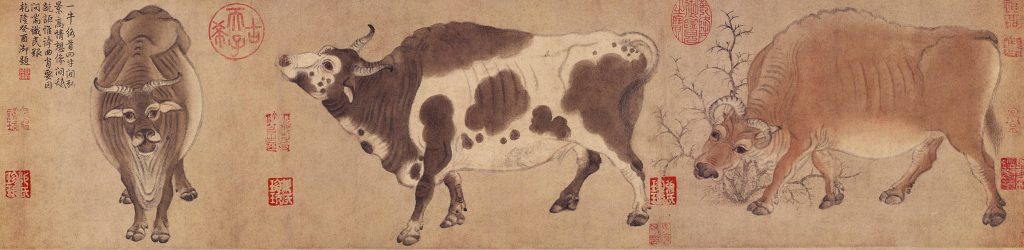

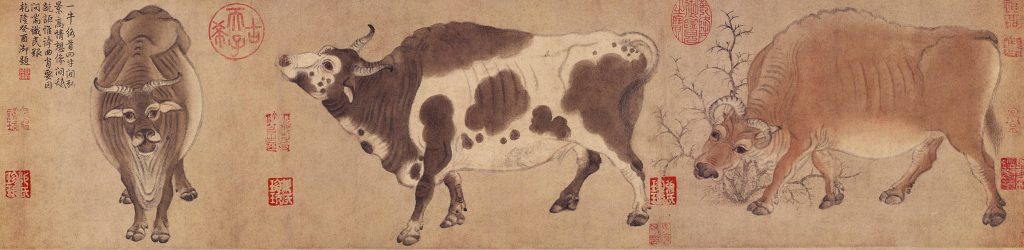

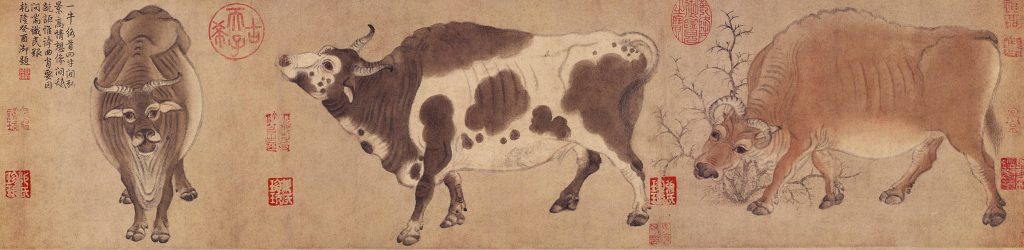

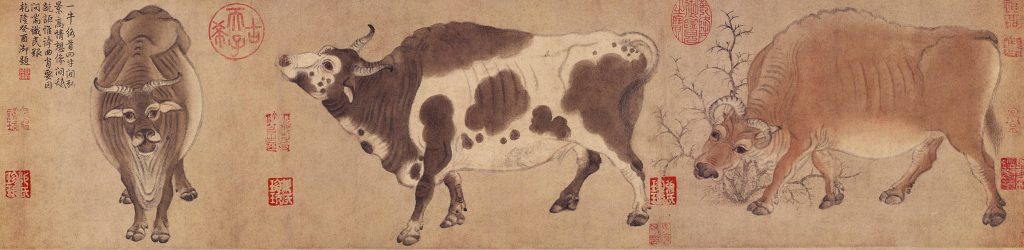

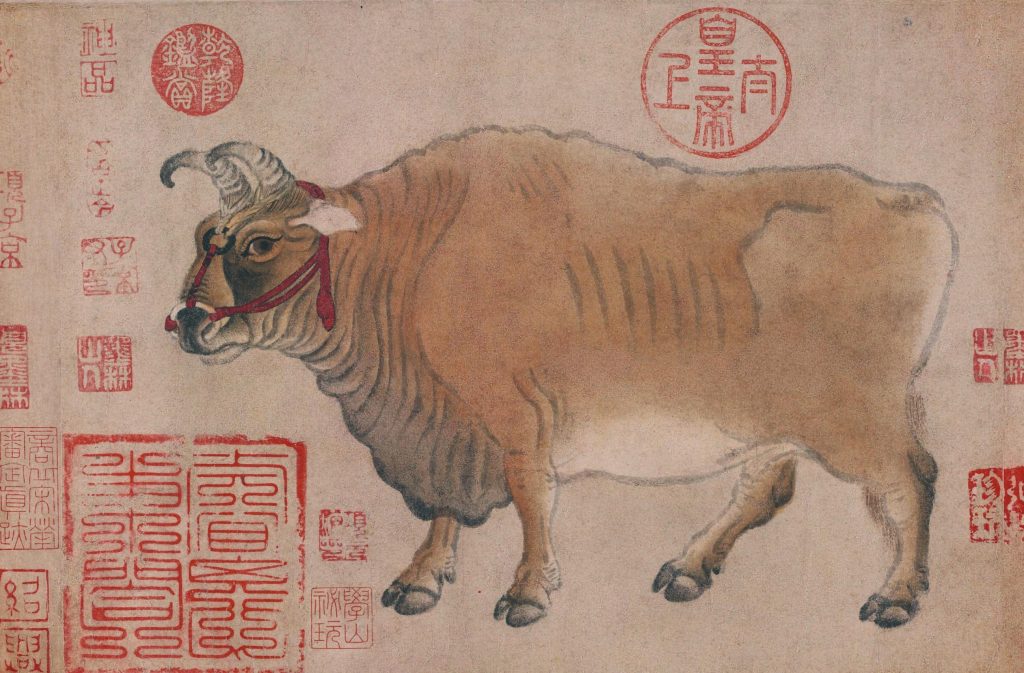

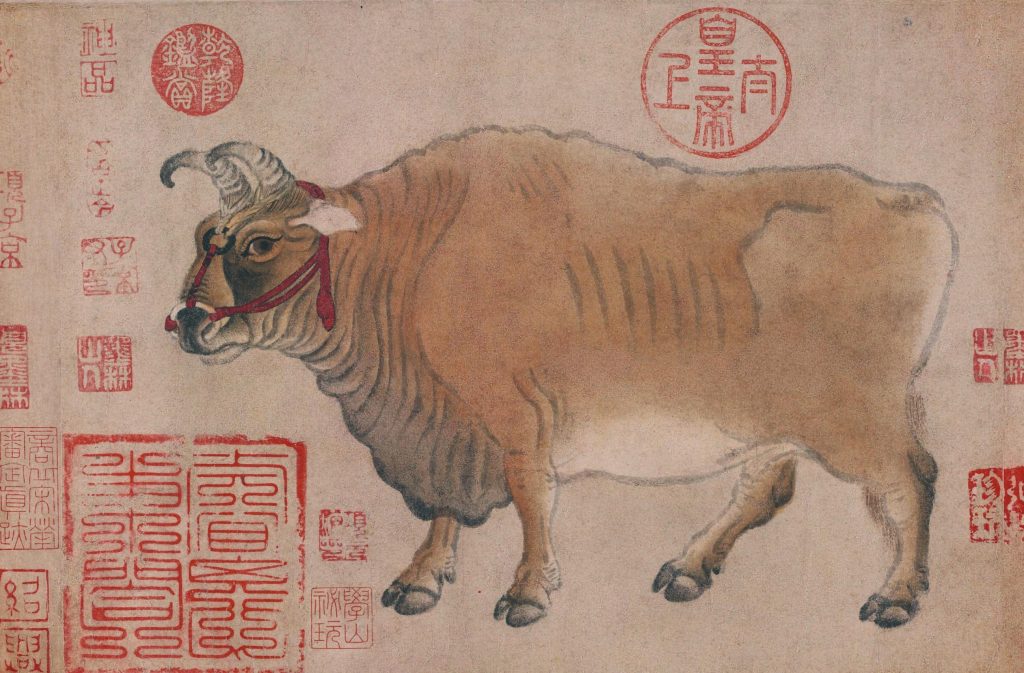

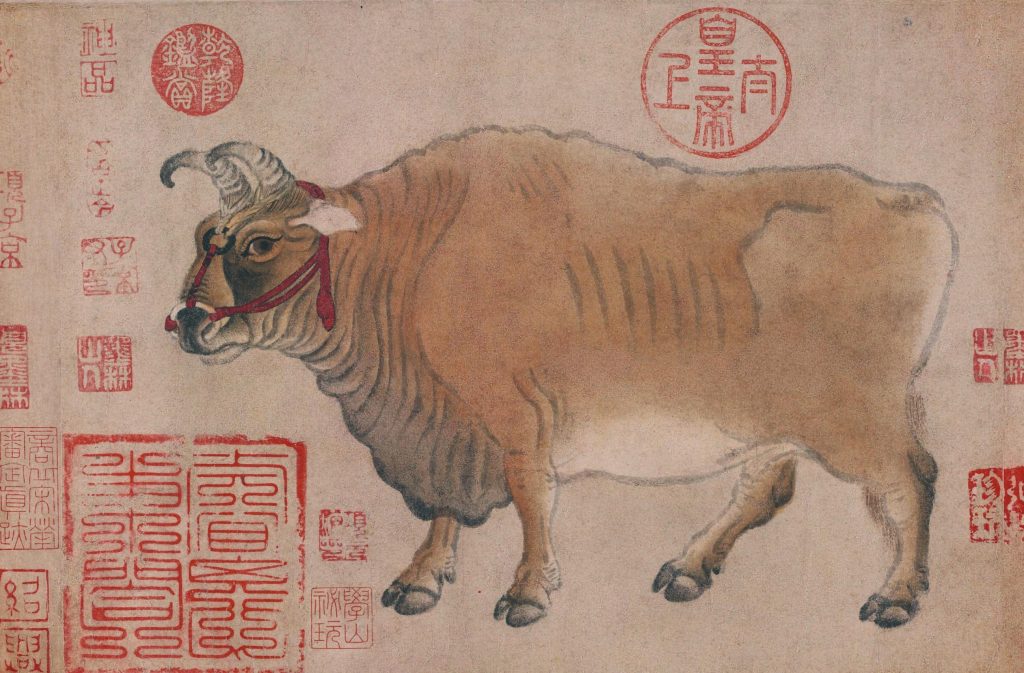

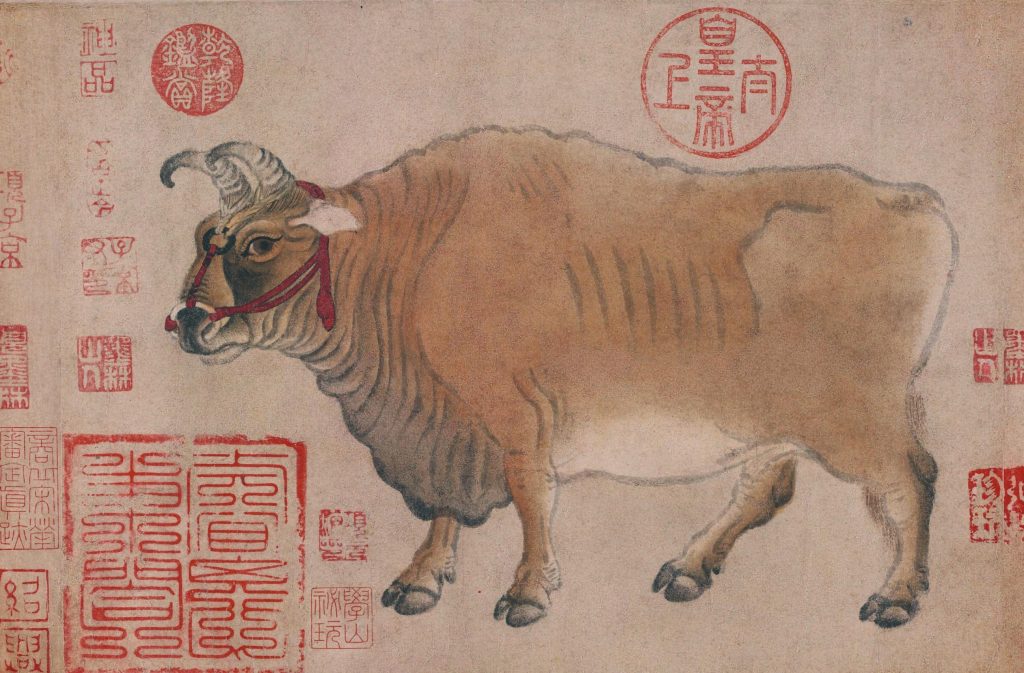

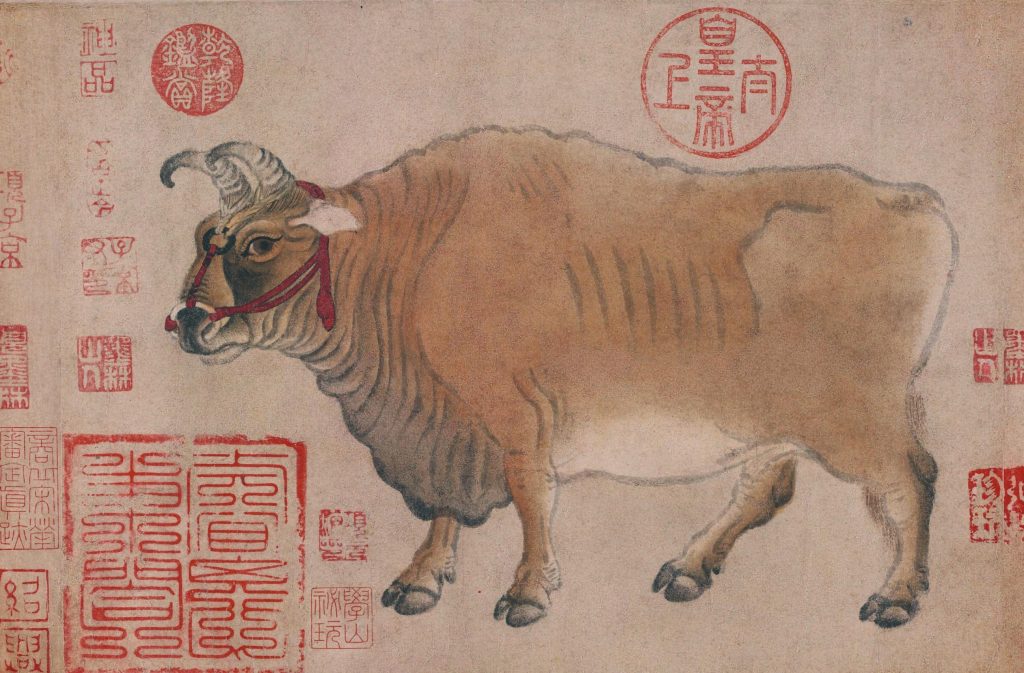

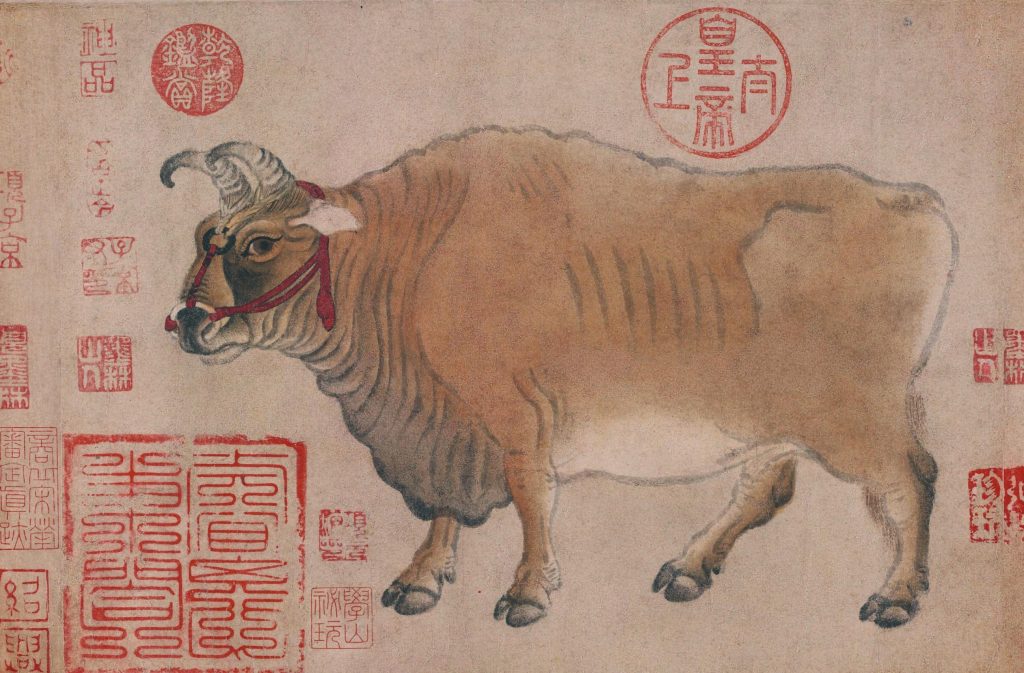

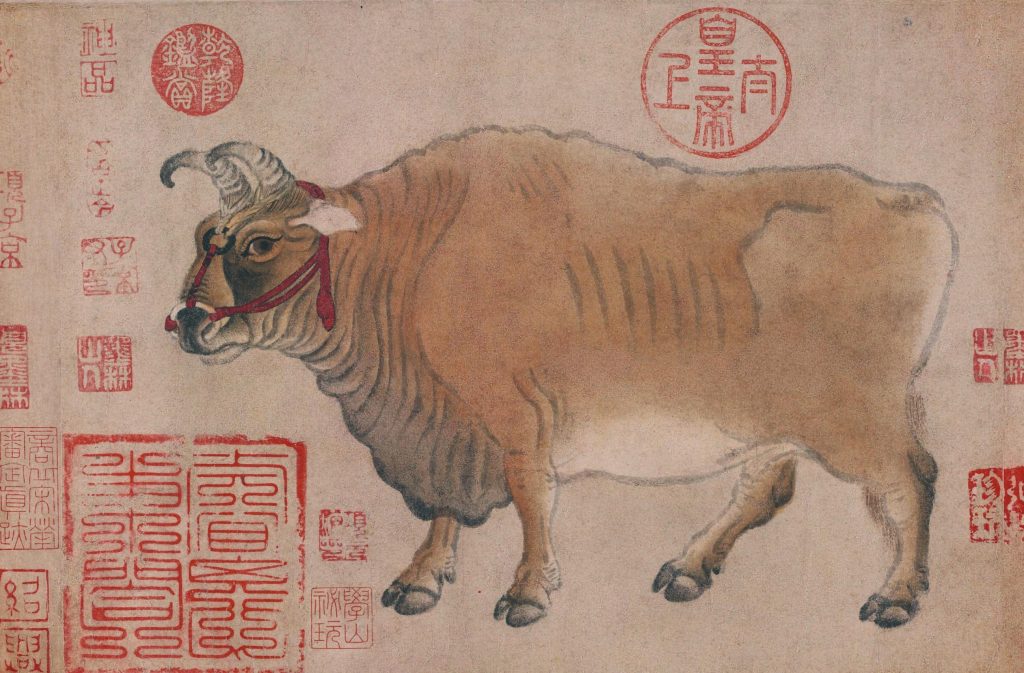

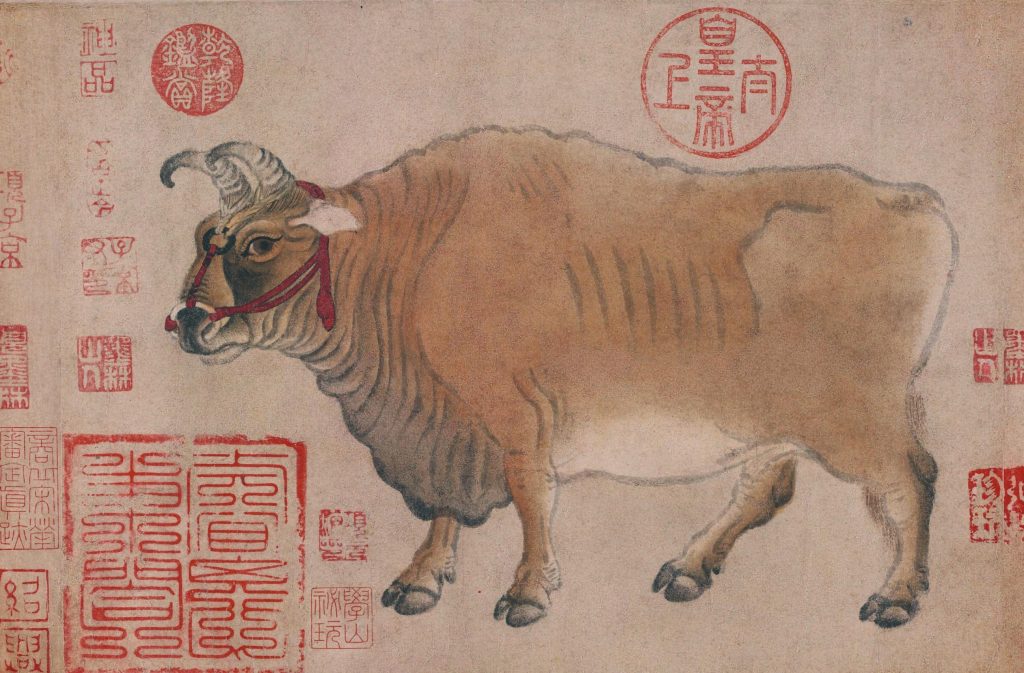

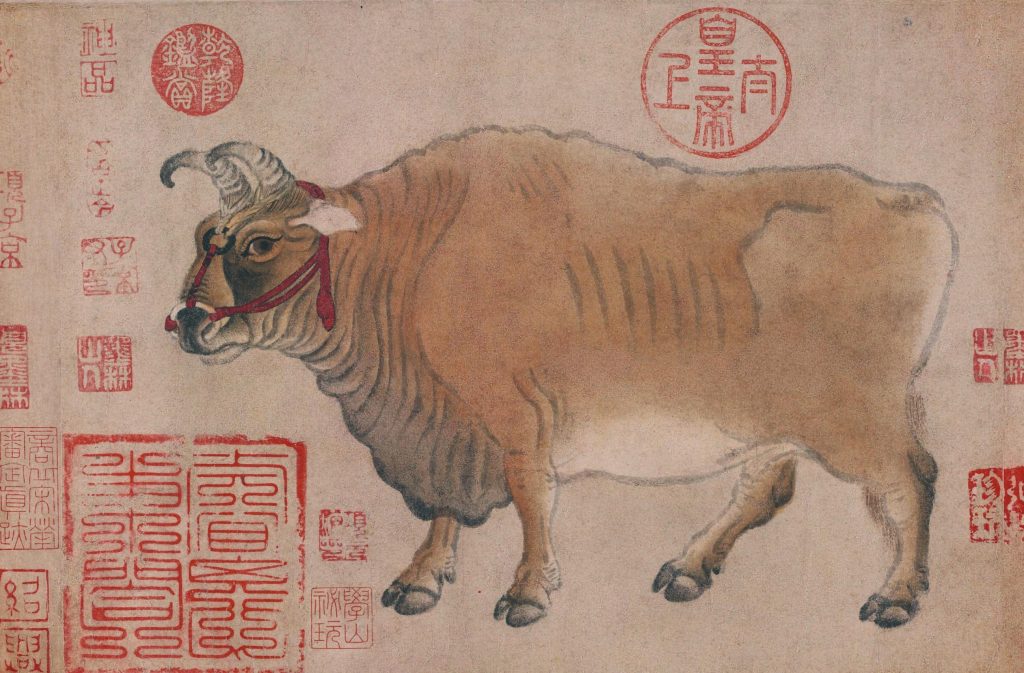

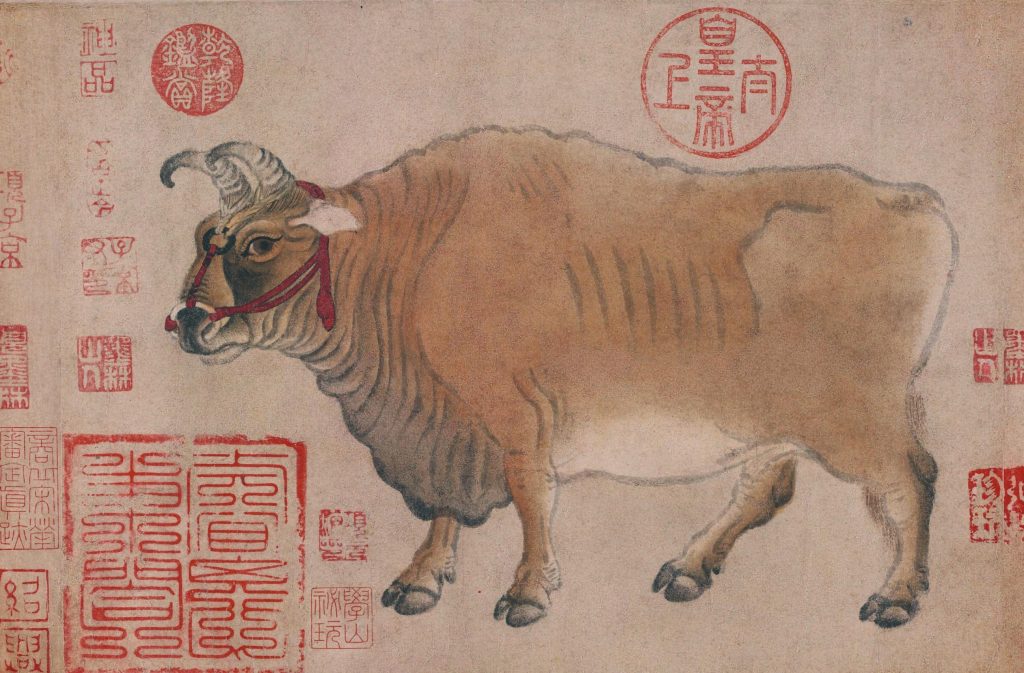

Han Huang (723–787), a chancellor of the Tang dynasty (618–907), painted his Five Oxen in different shapes from right to left. They stand in line and appear happy or depressed. We can treat each image as an independent painting. However, the oxen form a unified whole. Han Huang carefully observed the details. For example, horns, eyes, and expressions show different features of the oxen. They are all interesting characters, just like the five brothers. But which ox would you choose?

As for Han Huang, we do not know which ox he would choose and why he painted Five Oxen. In the Tang dynasty, horse painting was in vogue and enjoyed imperial patronage. By contrast, ox painting was traditionally considered an unsuitable theme for a gentleman’s study.

Did Han Huang compare himself to the ox with a rein? When he placed the ox with the bush in the same painting, he could imply that he preferred a retreat and a leisurely life on the mountain. However, judging by his career and high position, Han Huang probably did not want to go into seclusion. Therefore, by painting the ox with a rein, he could show his loyalty to the emperor.

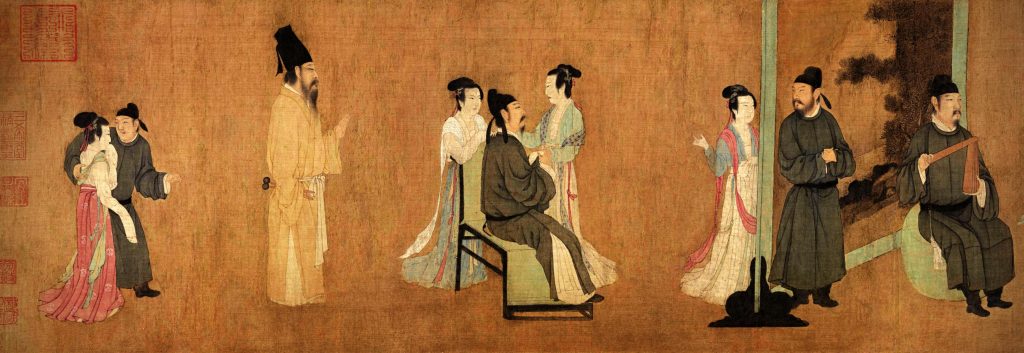

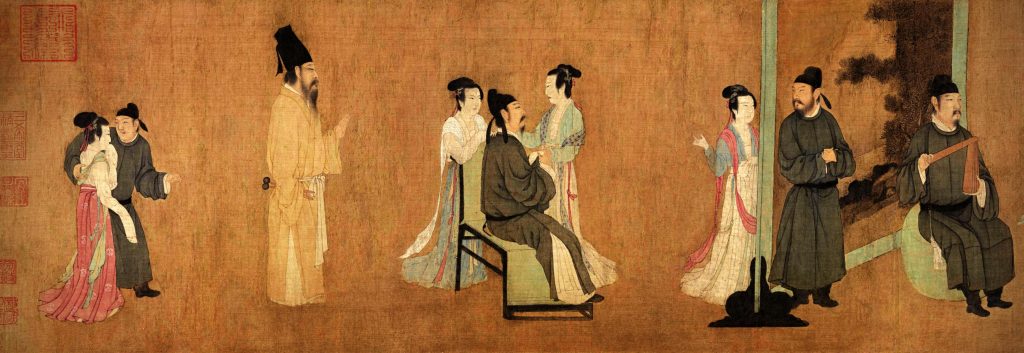

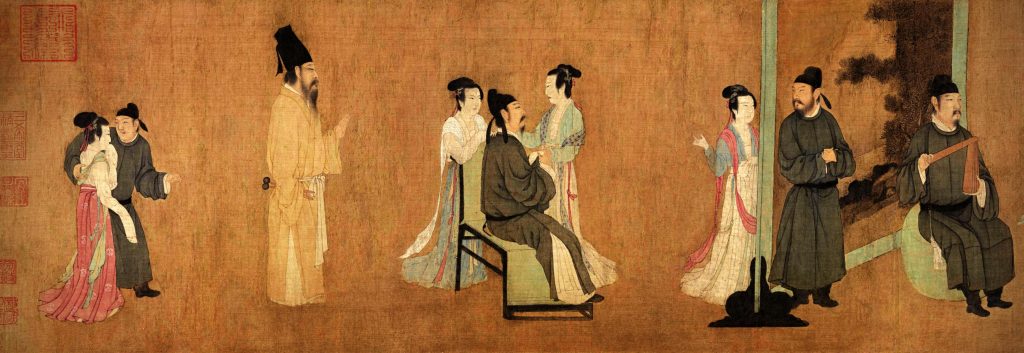

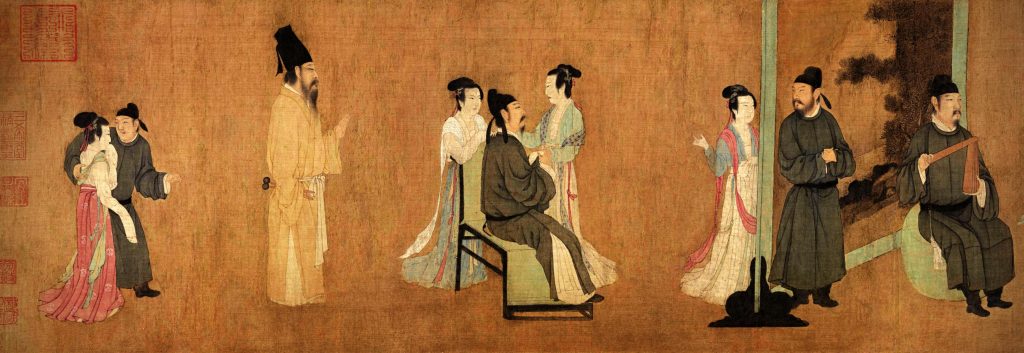

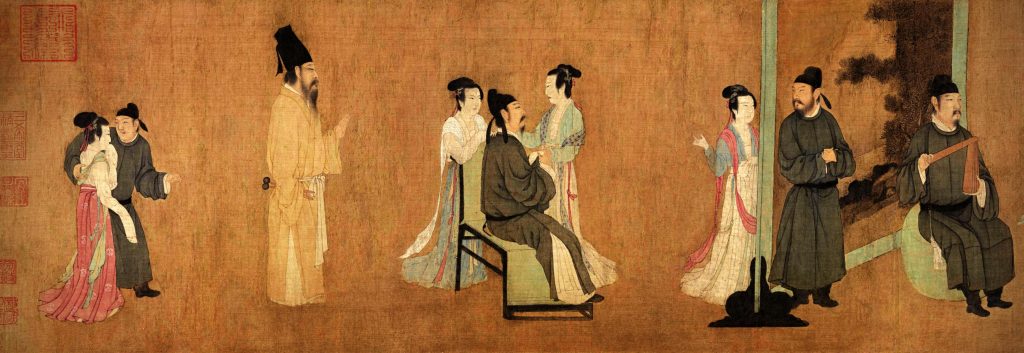

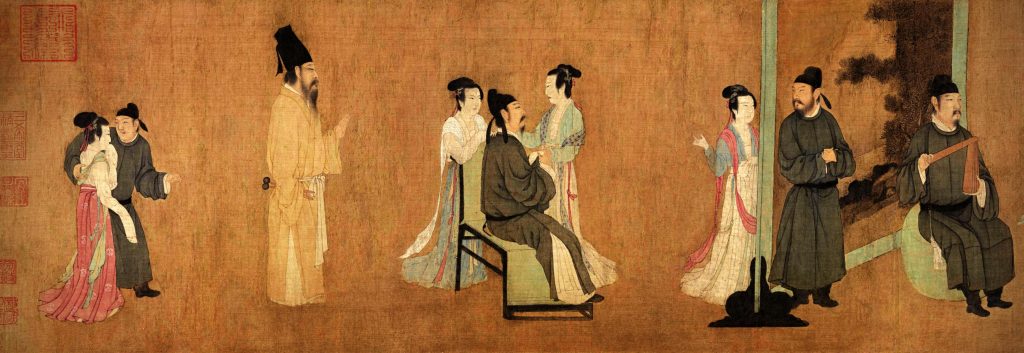

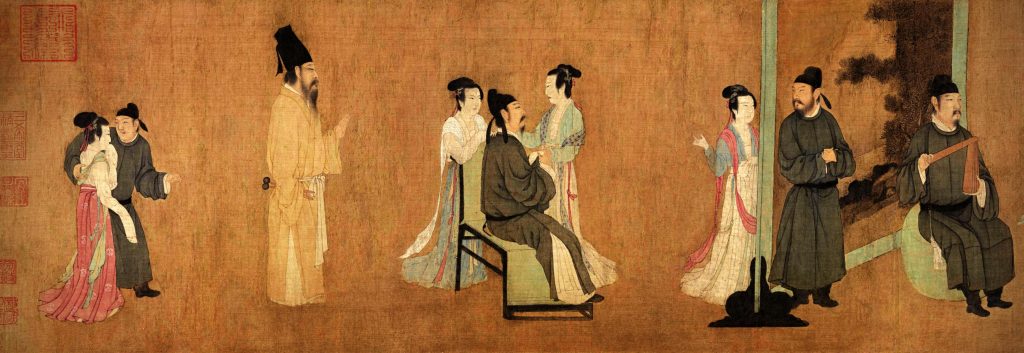

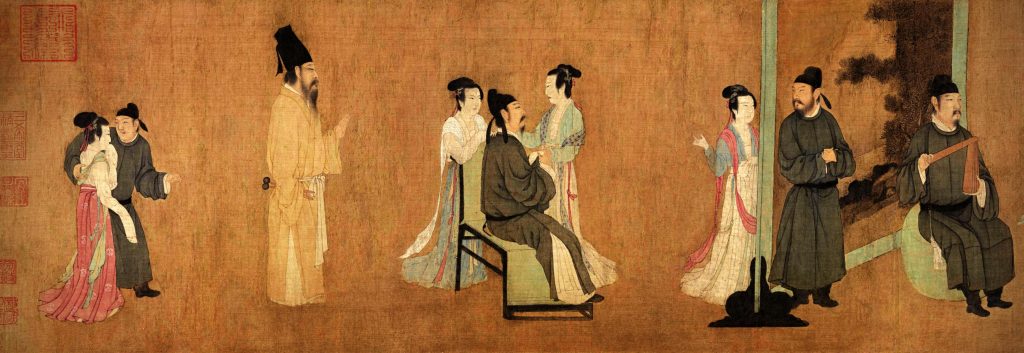

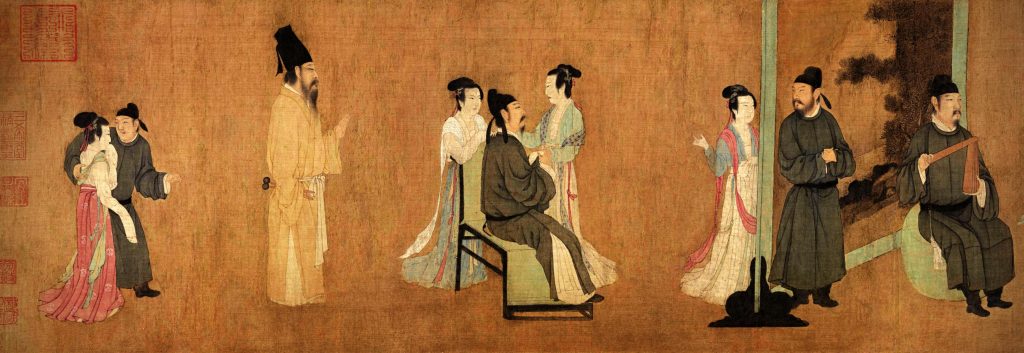

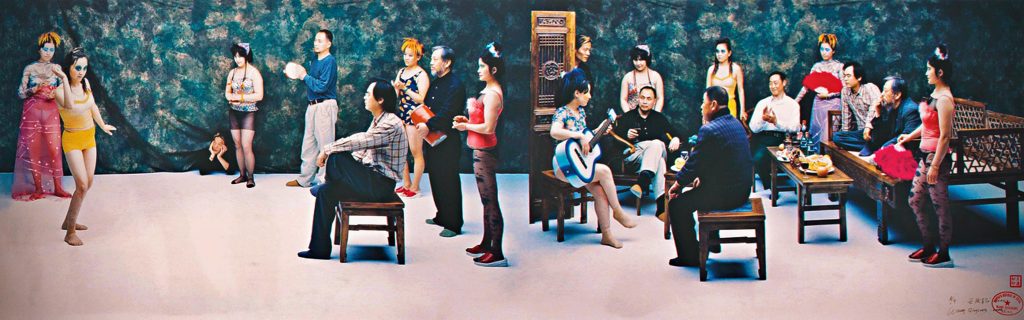

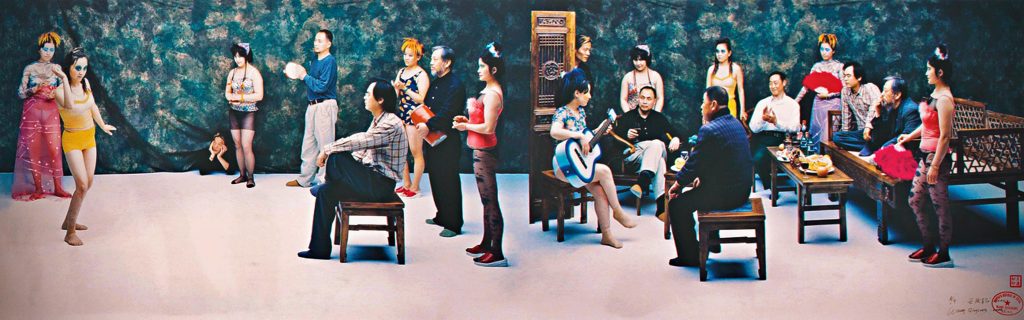

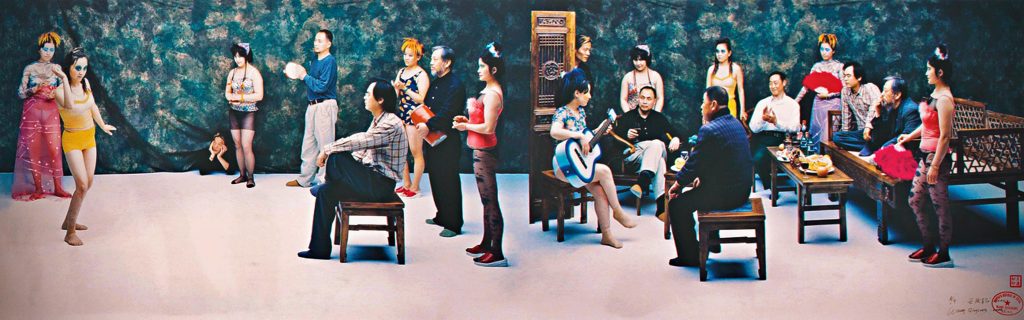

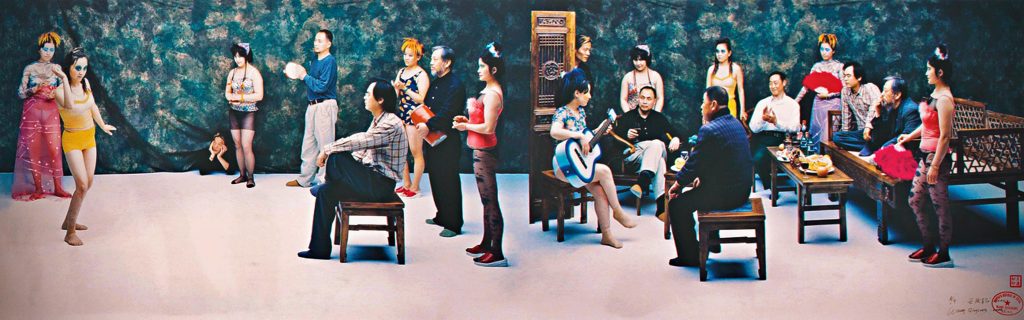

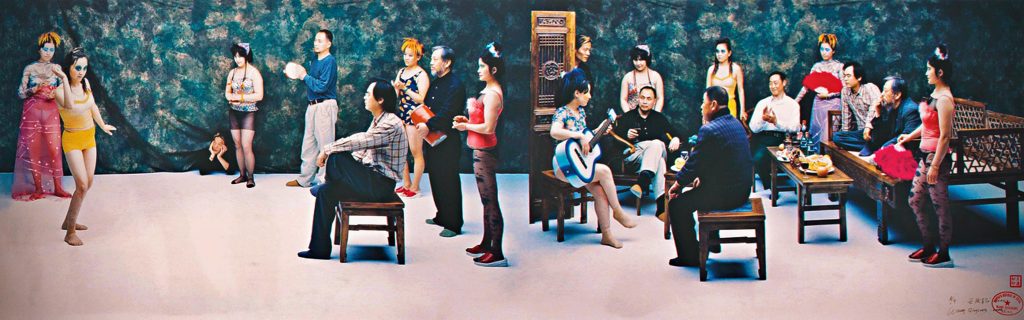

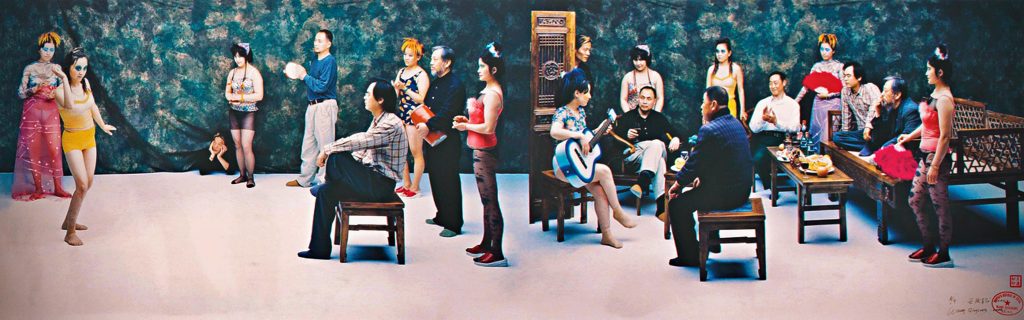

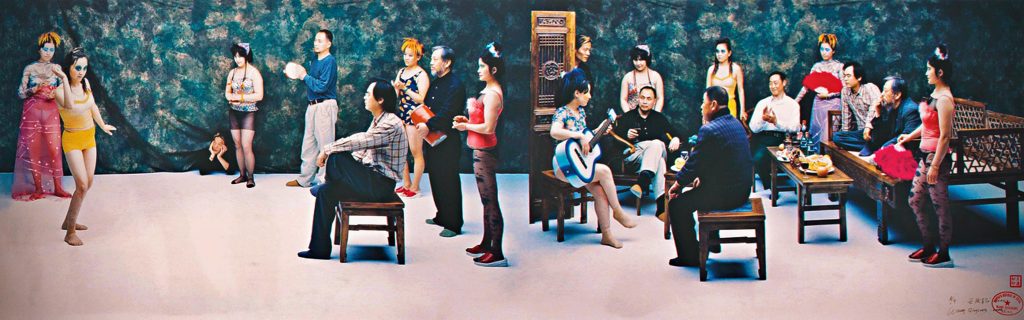

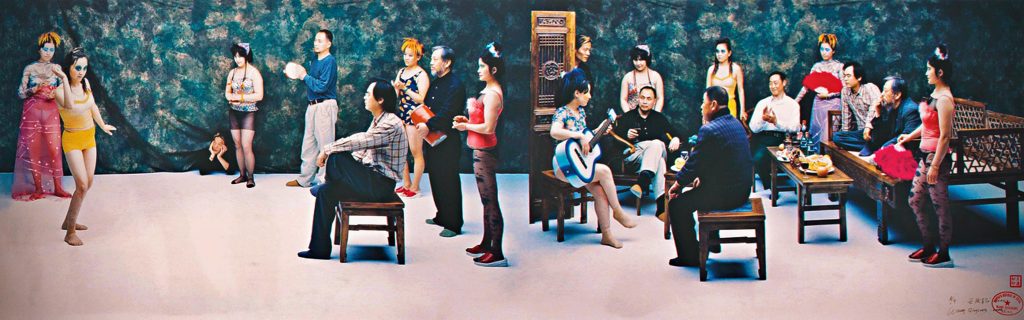

Suppose that you are Emperor Li Yu (ca. 937–978), but your official, Han Xizai, misses morning audiences with you and refuses to become prime minister. What would you do? You would try to find out what is going on, right? That is precisely what Li Yu did. To check what Han Xizai was doing at home, Li Yu sent Gu Hongzhong (937–975), a court painter. Therefore, he recorded what Han Xizai (902–970) did by painting The Night Revels of Han Xizai.

It turned out that Han Xizai was disillusioned with the regime. He refused to serve and instead, he was having fun and enjoying his life. Gu Hongzhong presents a continuous story, describing the whole scene as a narrative. The painting is divided into sections as the scene progresses, with the screens as dividers. There are more than forty figures in the painting, all lifelike and with different expressions.

For example, in the first scene, we can see Han Xizai in futou, a tall black hat, listening to the pipa, a Chinese musical instrument. The person in the red attire is a Chinese scholar. In the next scene, Han Xizai is beating a drum for the dancers. After a break, he continues to further entertain himself and listens to the music, meanwhile, his guests talk with the singers.

Gu Hongzhong cleverly arranges the composition. Each scene is relatively independent, but the composition is unified. The artist places a candlestick in one of the scenes to point out the specific time. At first glance, this painting is about personal life. However, it also hints at many customs of that period.

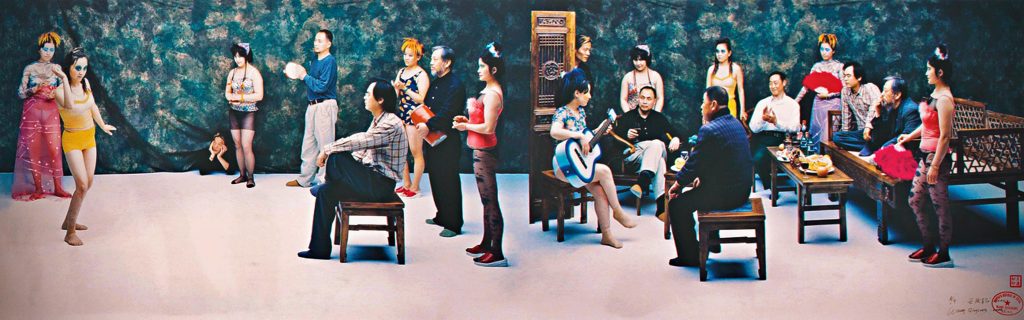

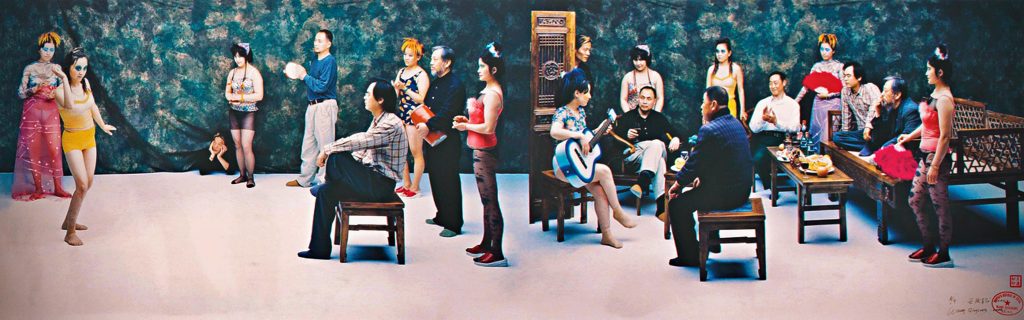

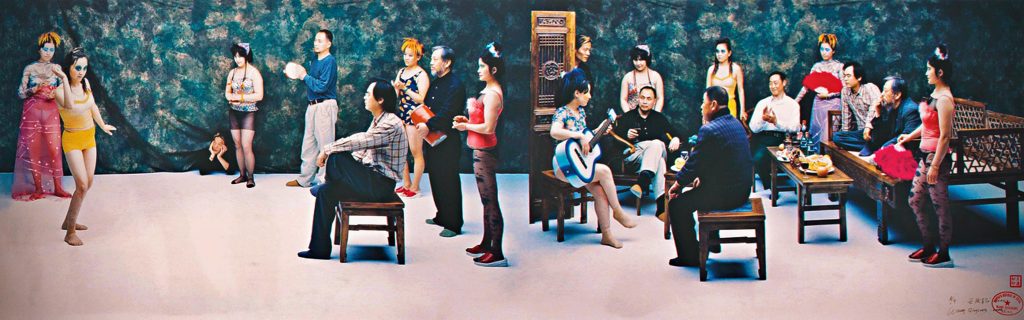

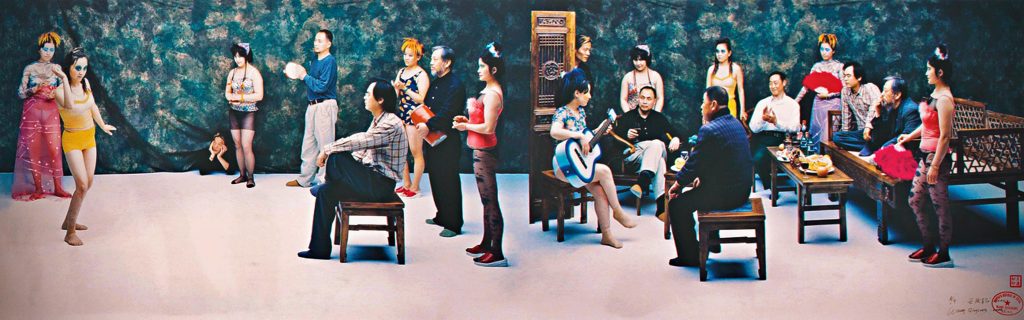

In 2000, Wang Qingsong, a conceptual artist, created The Night Revels of Lao Li based on Gu Hongzhong’s work. In his photograph, he shows his characters in contemporary clothes to comment on current Chinese culture. His guests include average-looking men, dressed in plain casual slacks and dark shirts, lounging in house slippers. Here, Wang Qingsong is not a spy for the state or imperial court. He turned into a kind of cultural spy, appearing as a curious outsider to this strange, artificial world.

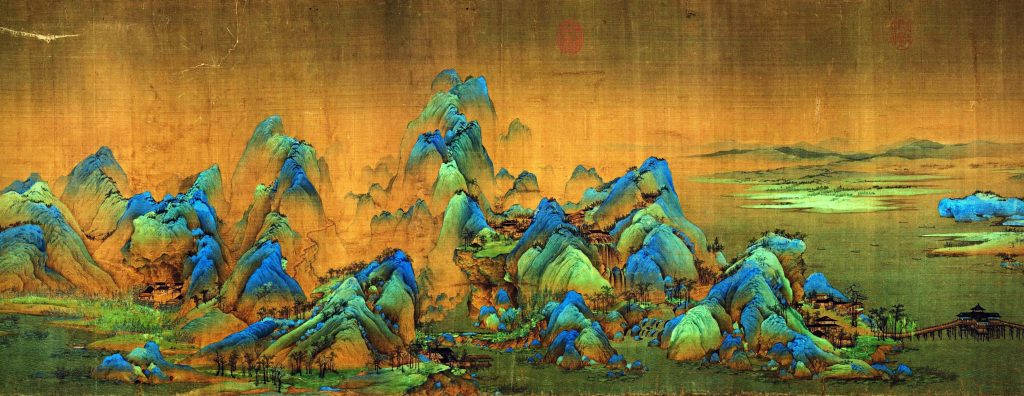

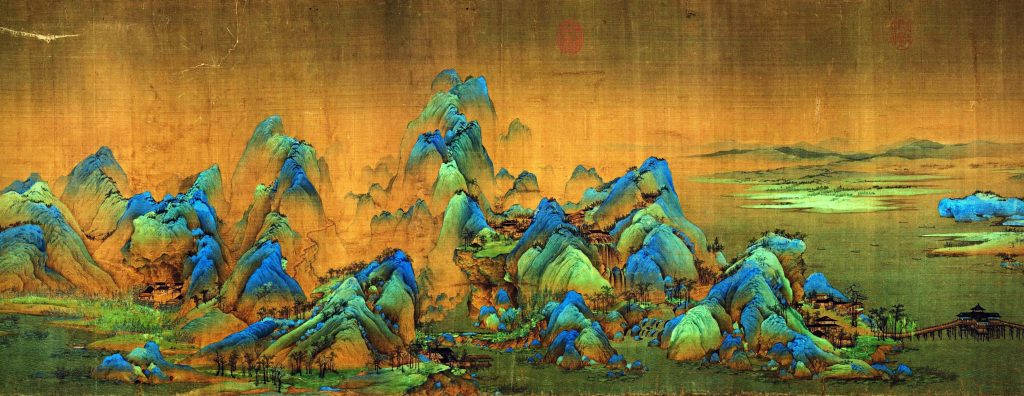

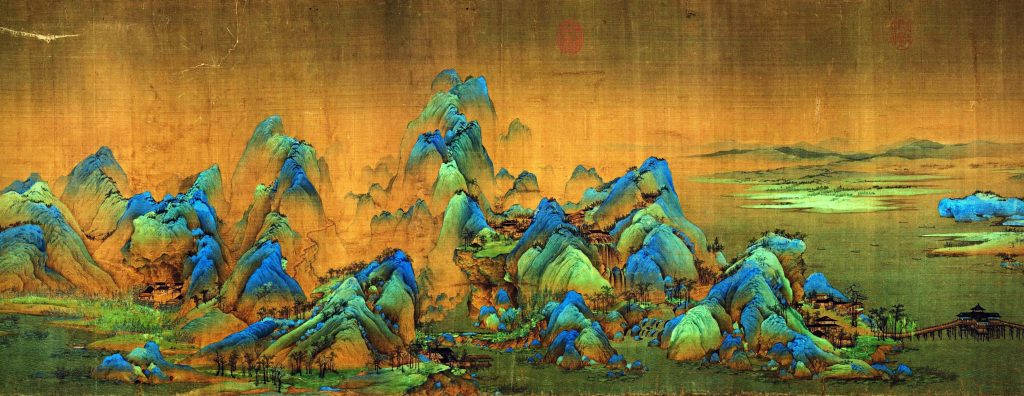

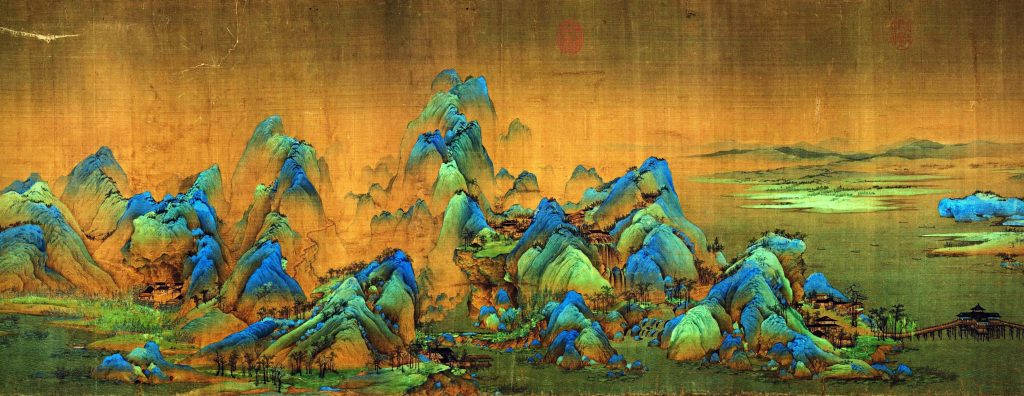

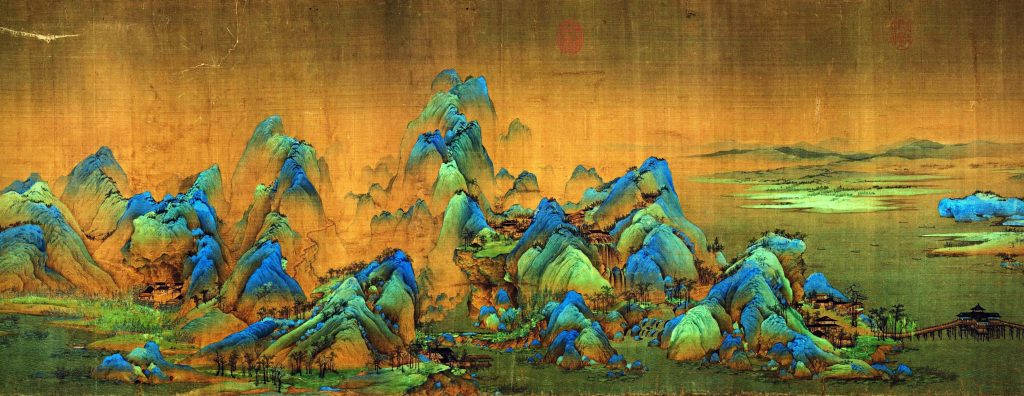

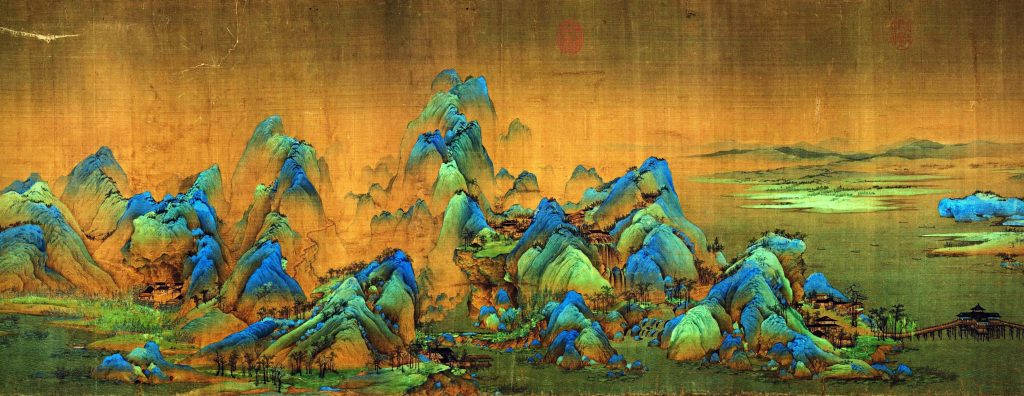

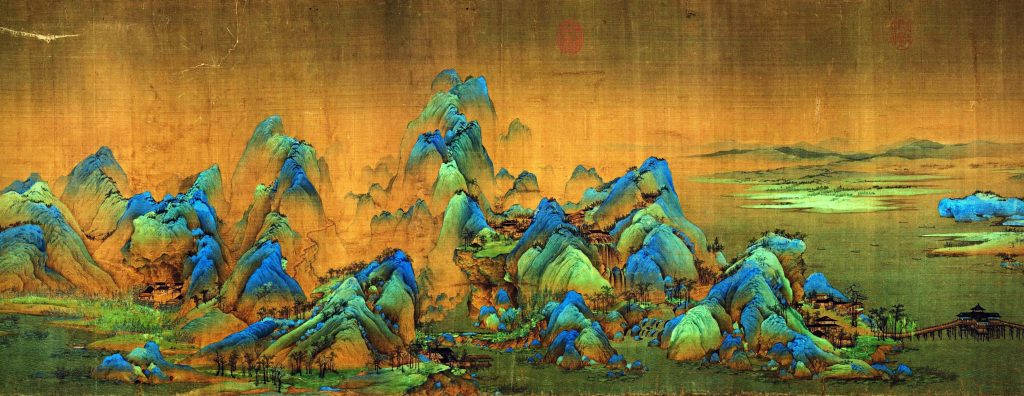

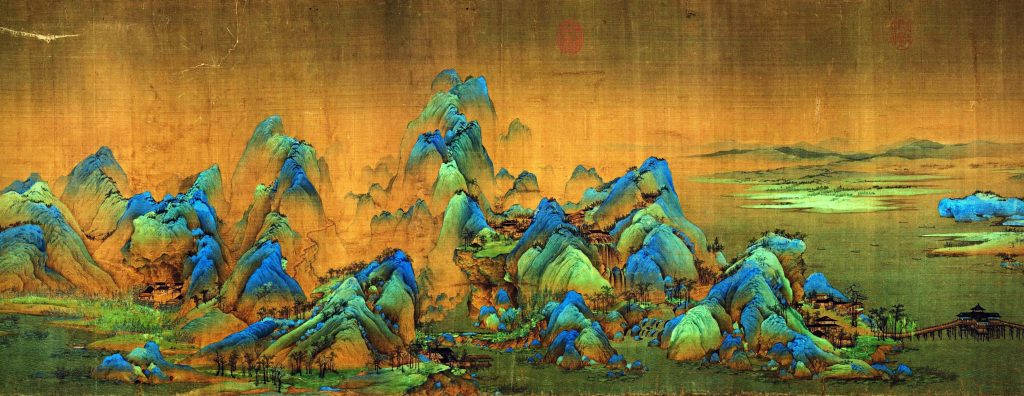

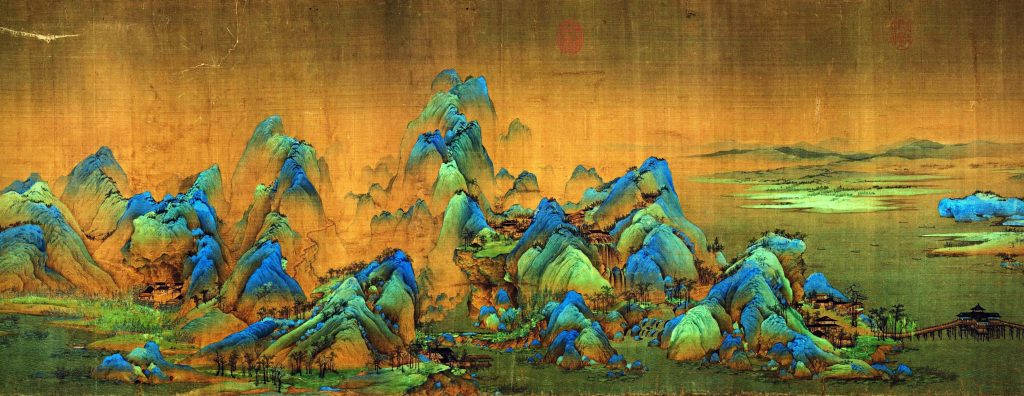

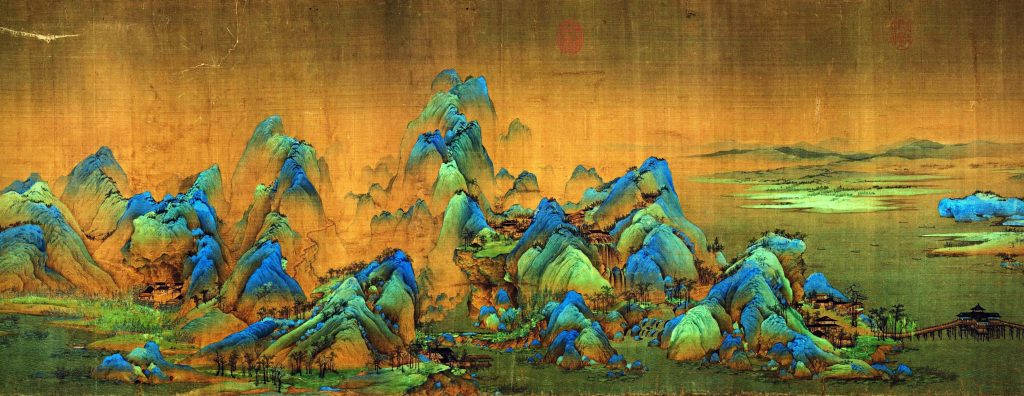

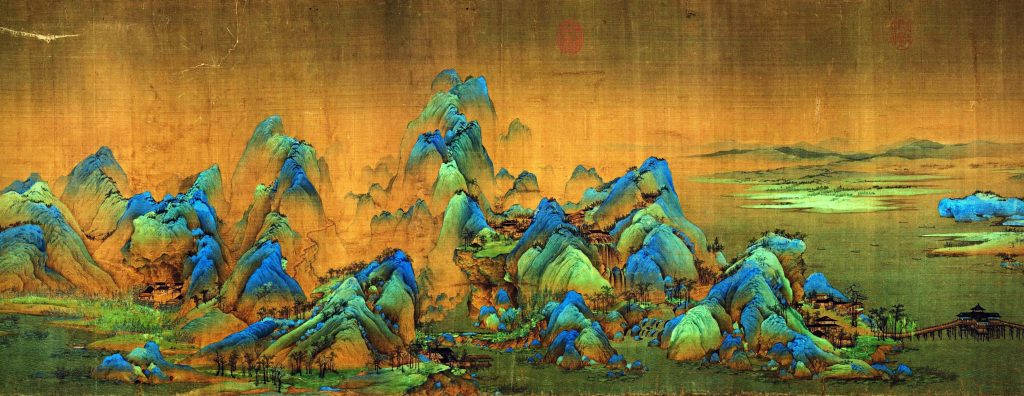

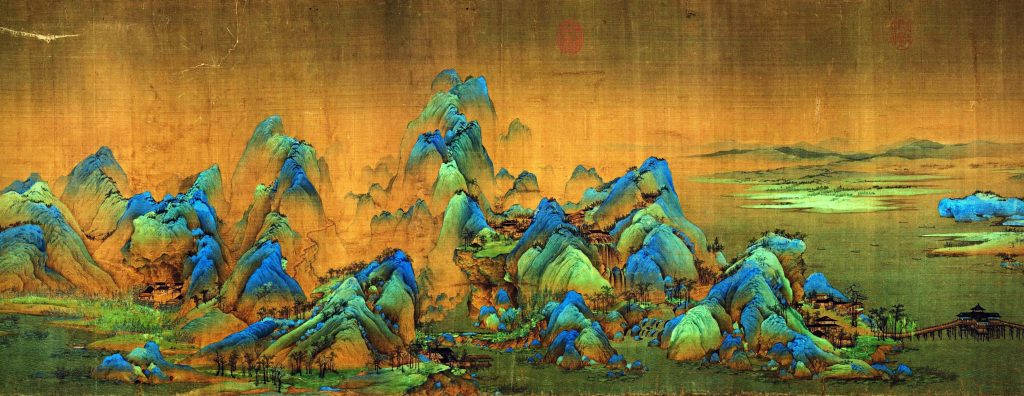

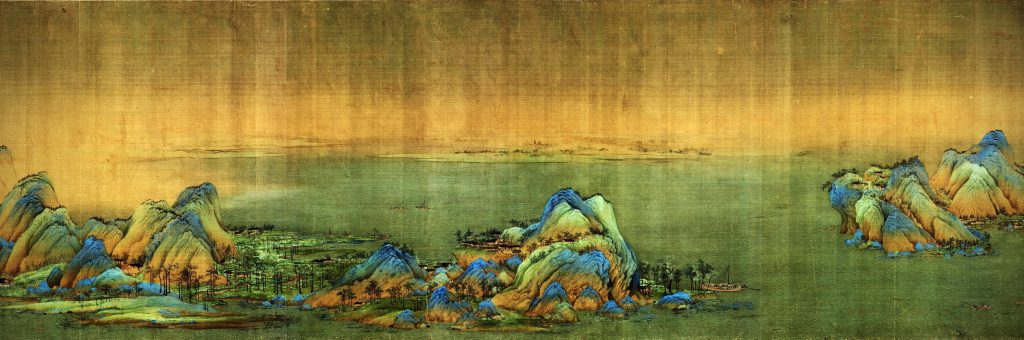

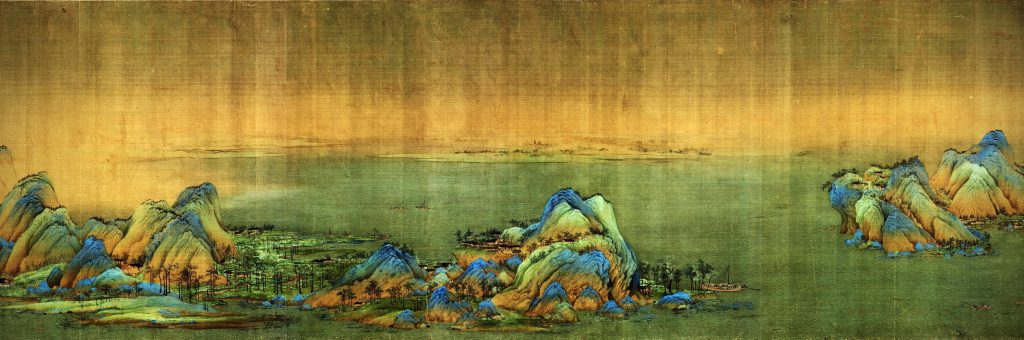

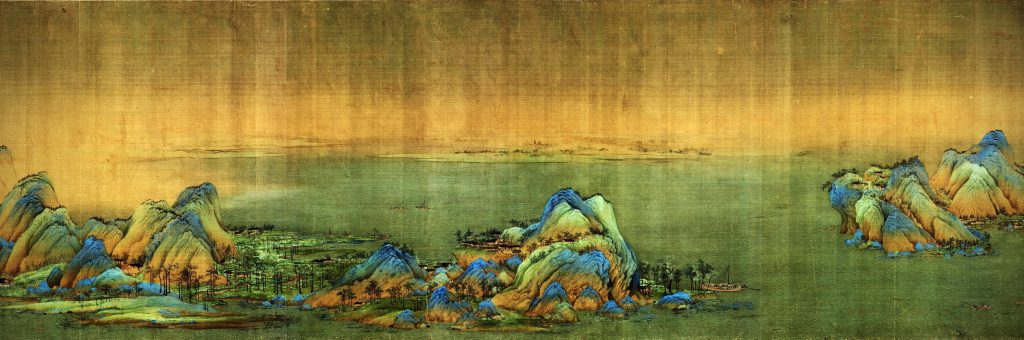

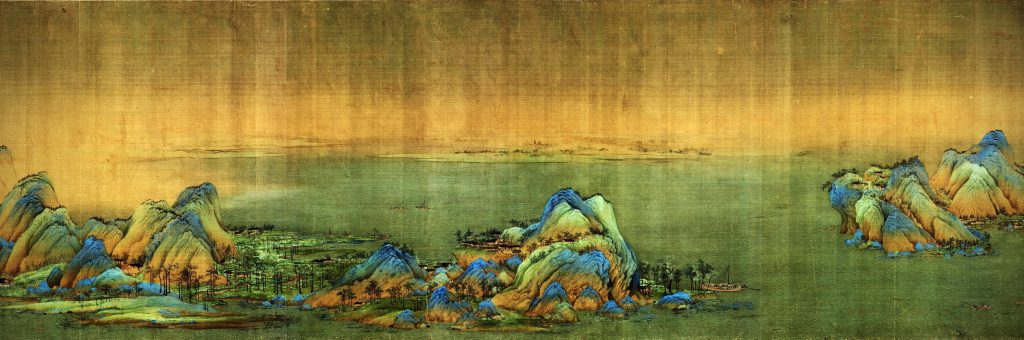

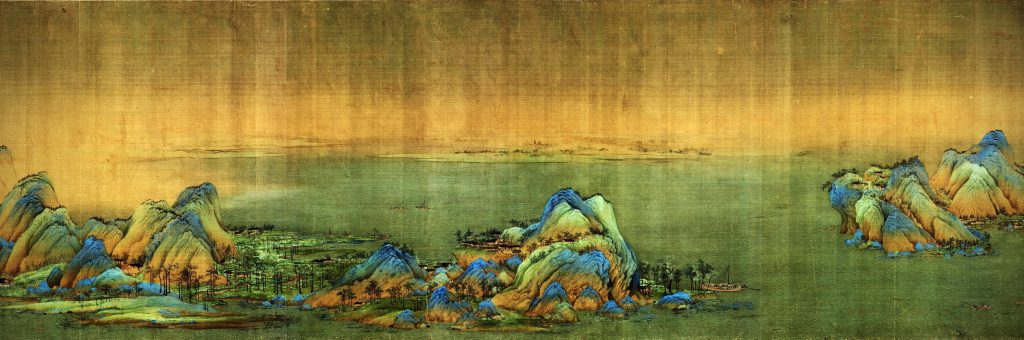

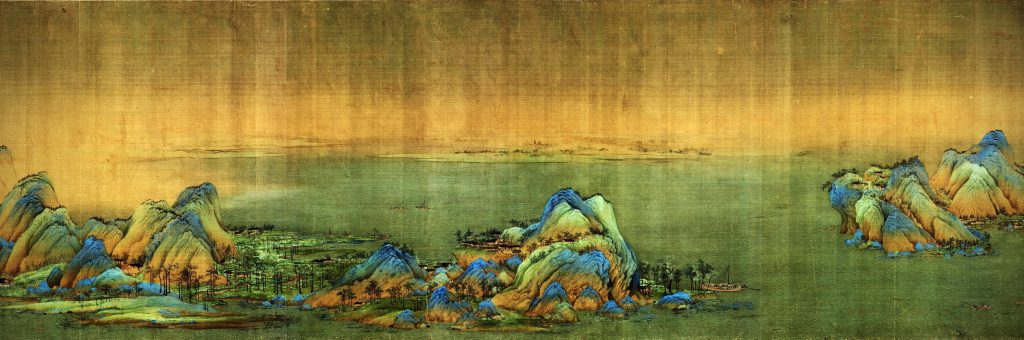

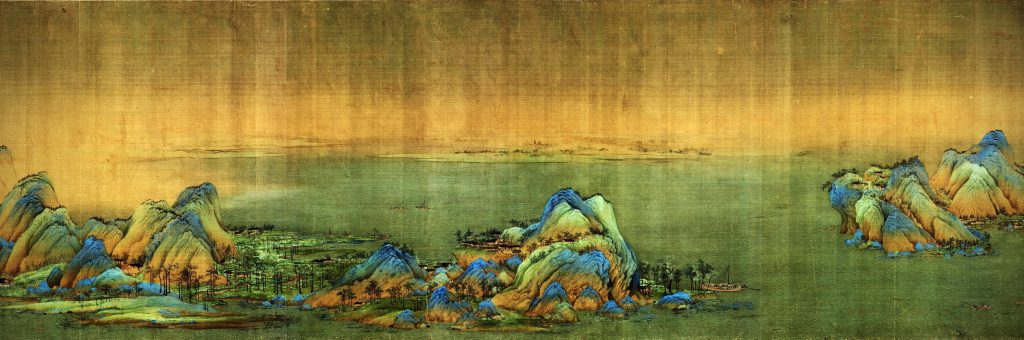

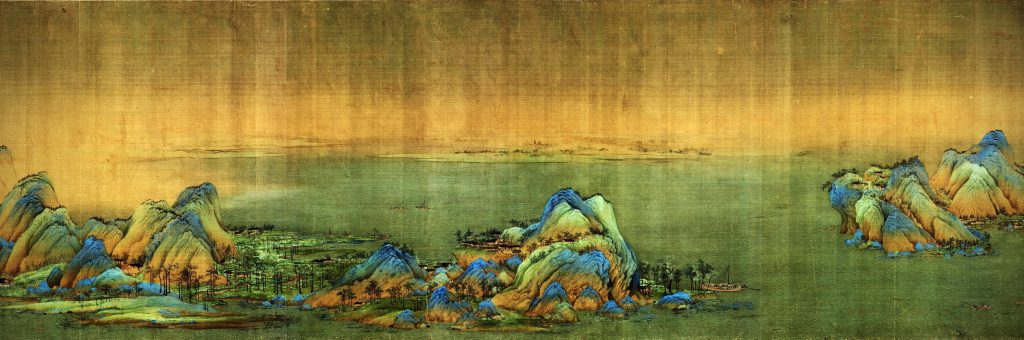

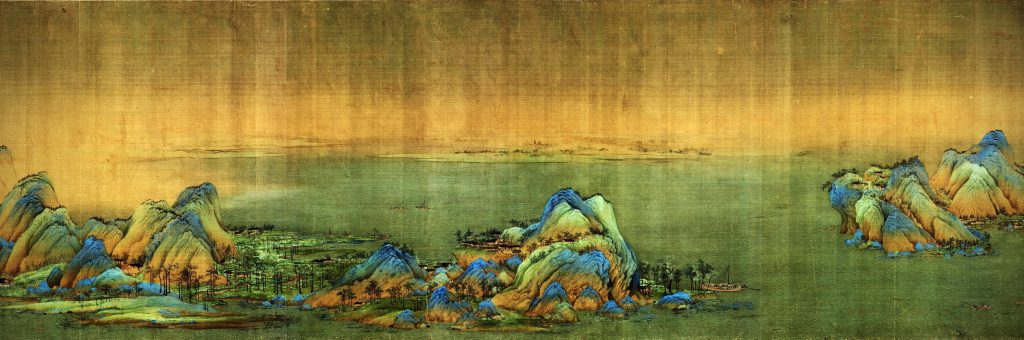

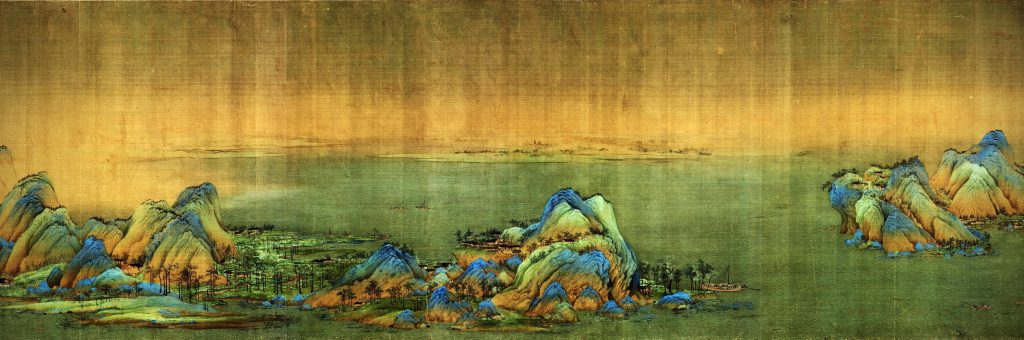

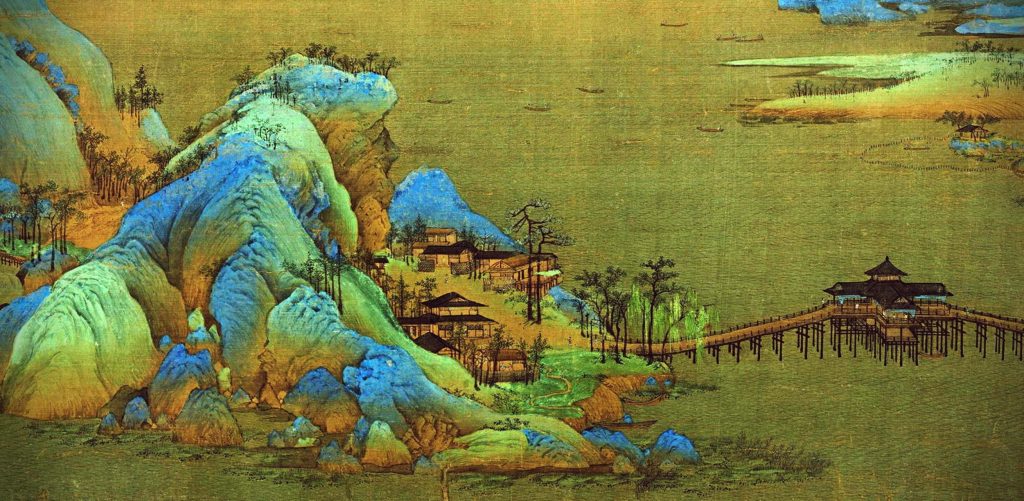

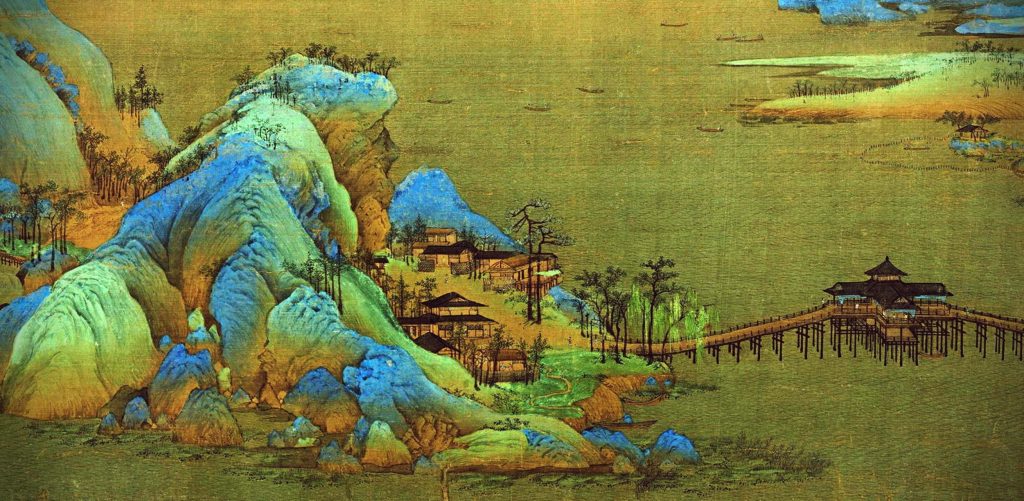

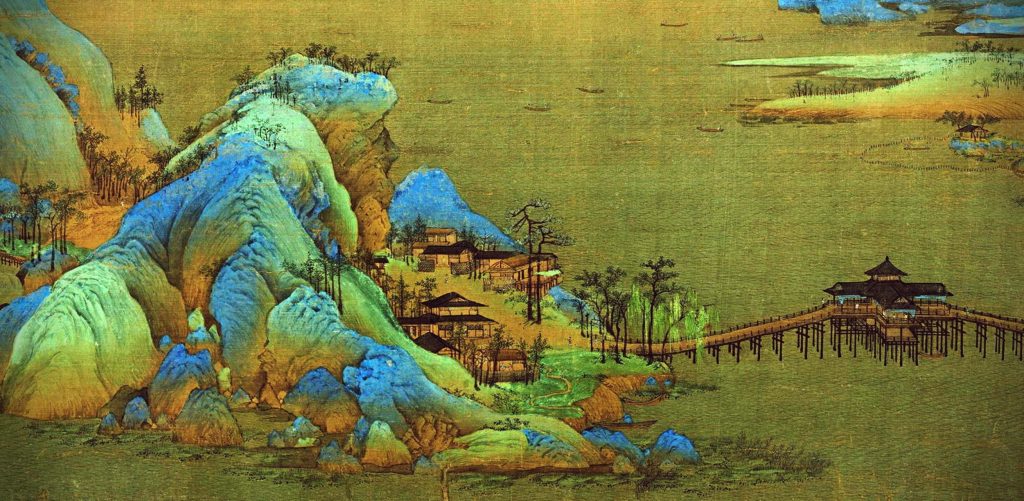

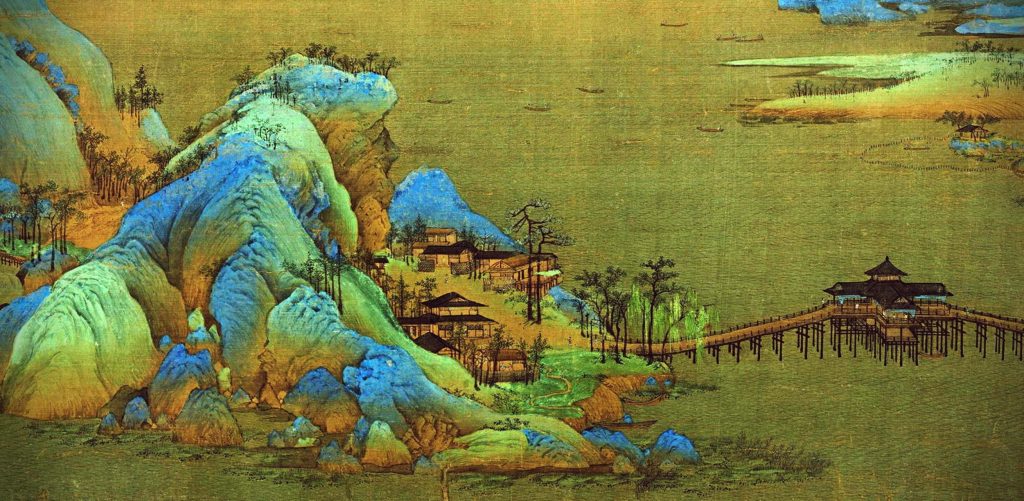

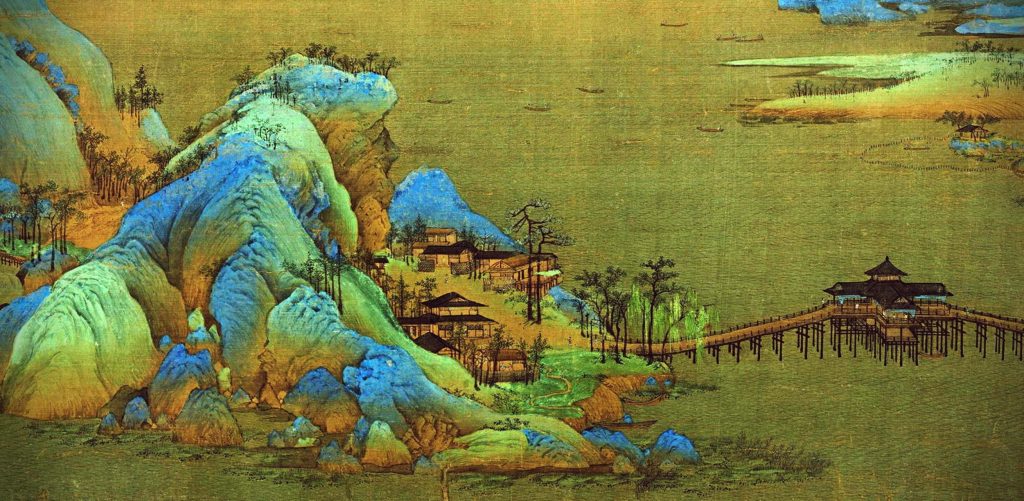

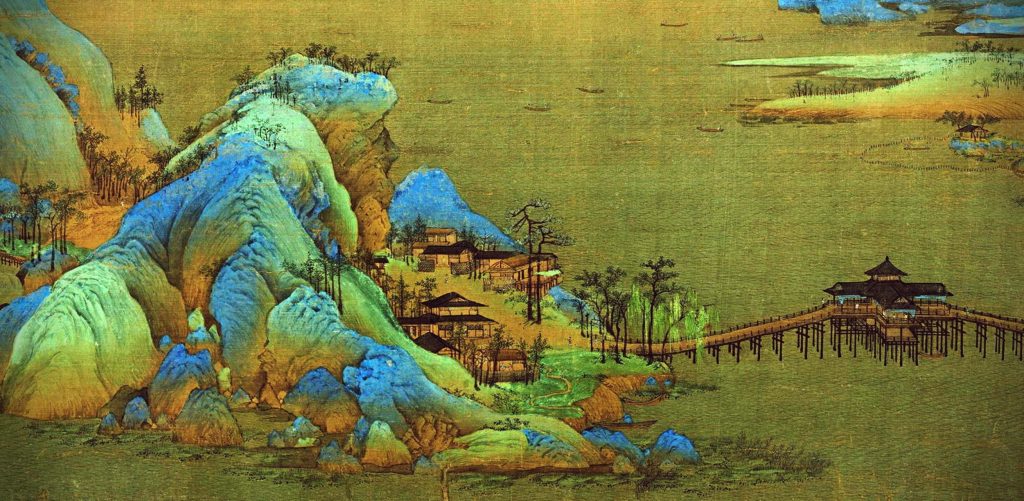

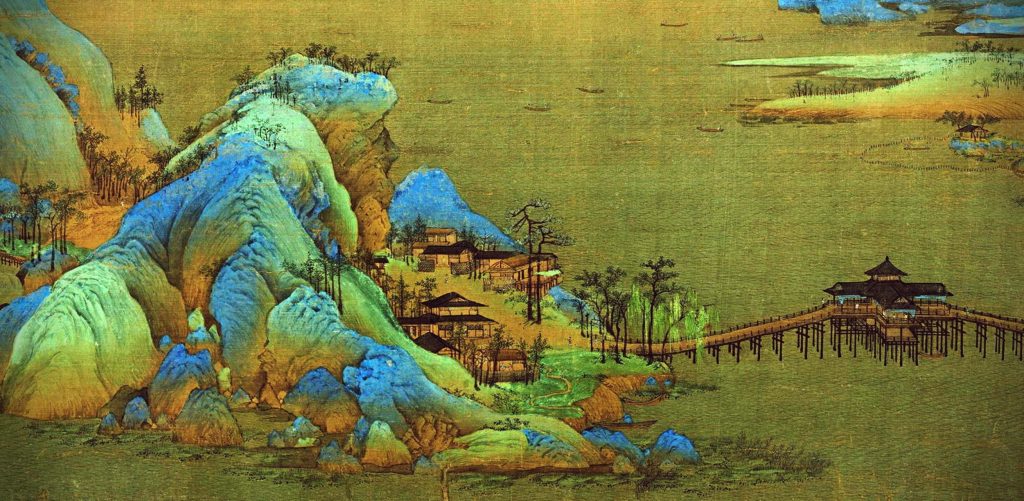

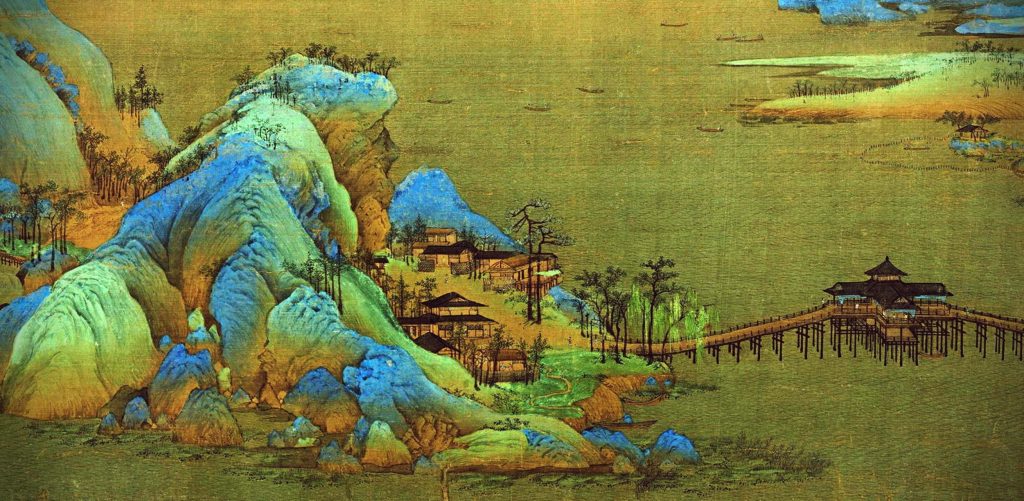

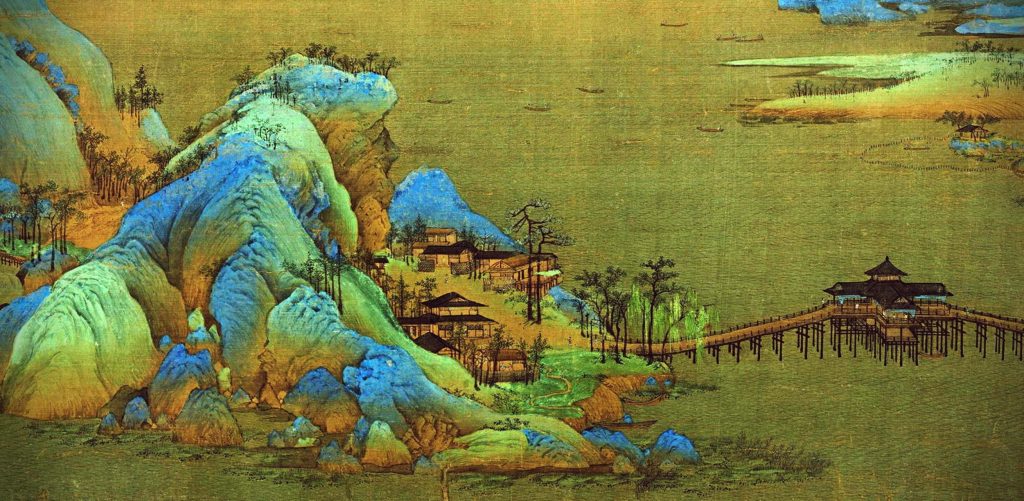

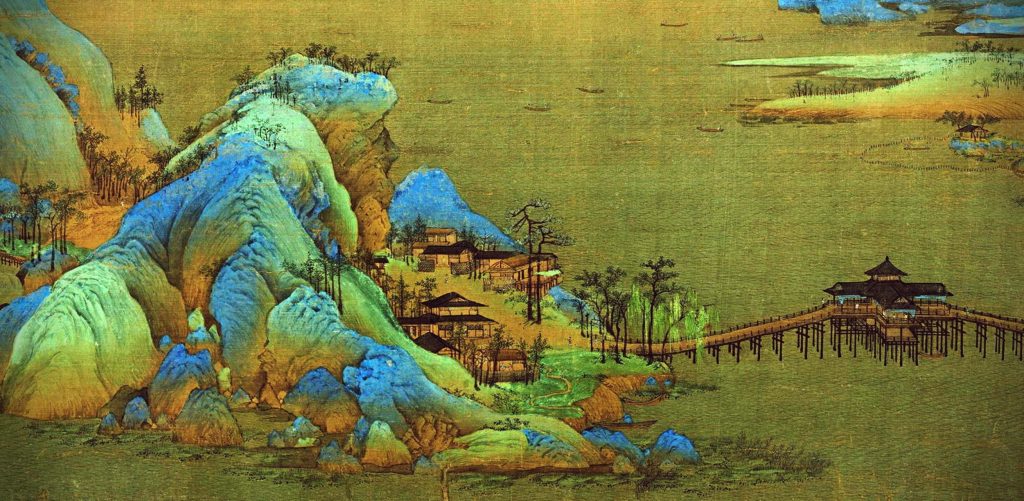

Not only did officials and scholars revel in listening to music but they also found pleasure in depicting nature. One such painter was Wang Ximeng (1096–1119). He was a prodigy and Emperor Huizong of Song supposedly taught the artist. Wang Ximeng painted A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains when he was only 17 years old in 1113. He died several years later but left one of the largest and most beautiful paintings in Chinese history. It is nearly twelve meters in length.

The painting is a masterpiece of a “blue-green landscape.” Azurite blue and malachite green dominate, and the artist also uses touches of pale brown. Wang Ximeng employs multiple perspectives to present a landscape. He shows us all the richness of the scenery with its green hills, temples, cottages, and bridges. The image is stunning in its sweeping scale, vivid colors, and minute details. If you zoom in, you can even see winding paths leading to secluded spots.

With meticulous brushwork and superb technique, the artist expresses deep admiration for the grandeur of nature. In his painting, mountain formations rise and fall between a cloudless sky. Thus, Wang Ximeng opened up a new world, a landscape you will never be tired of exploring.

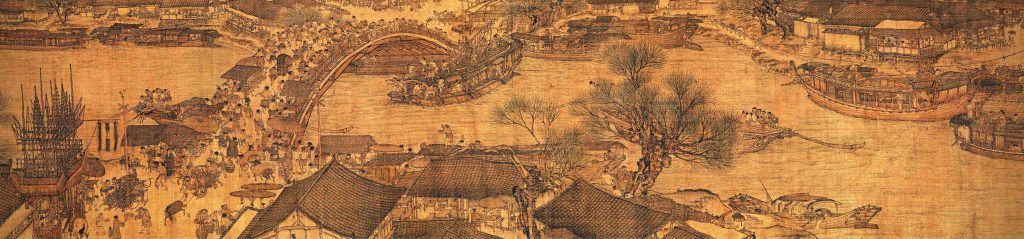

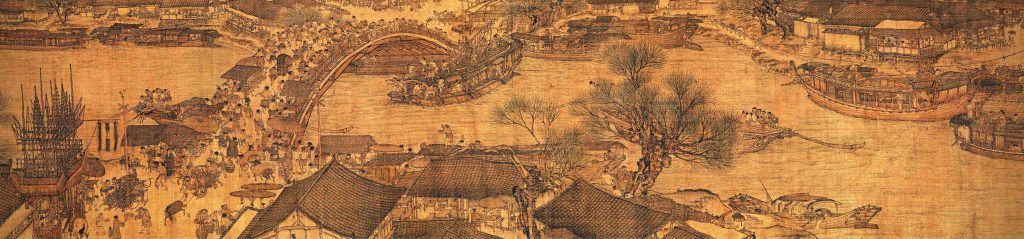

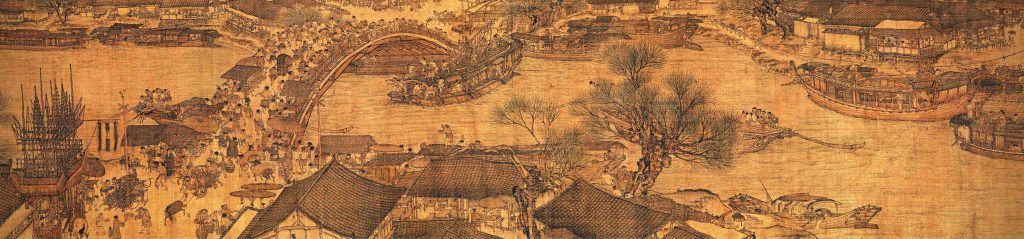

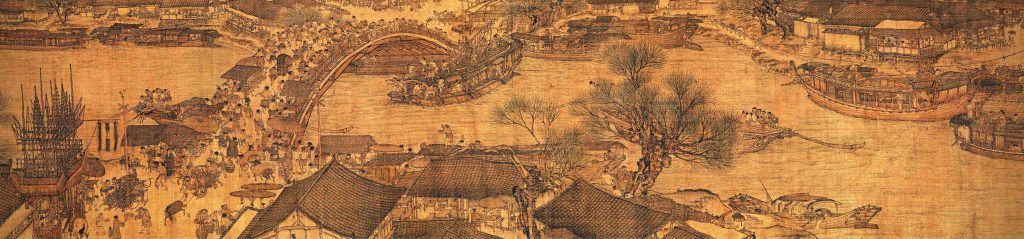

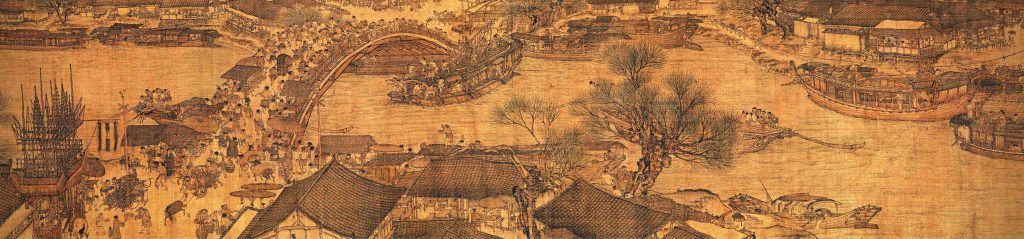

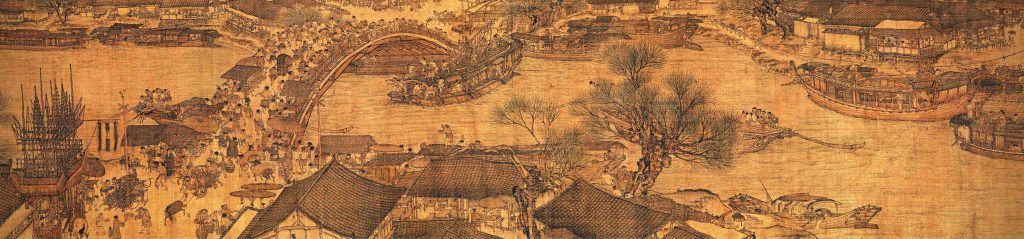

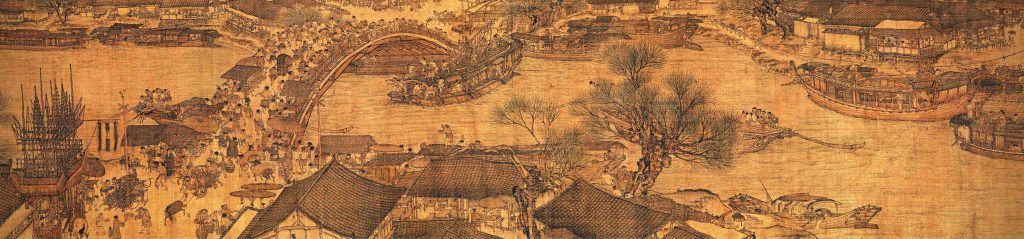

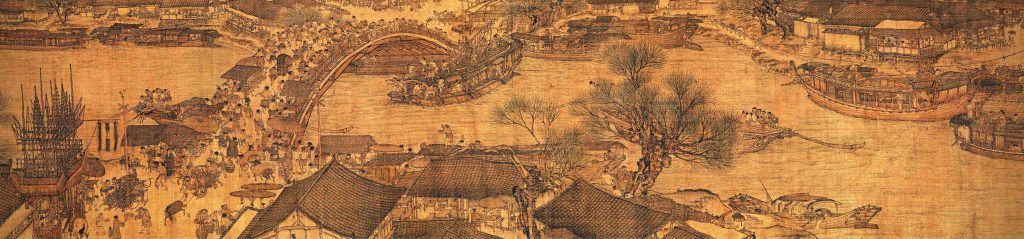

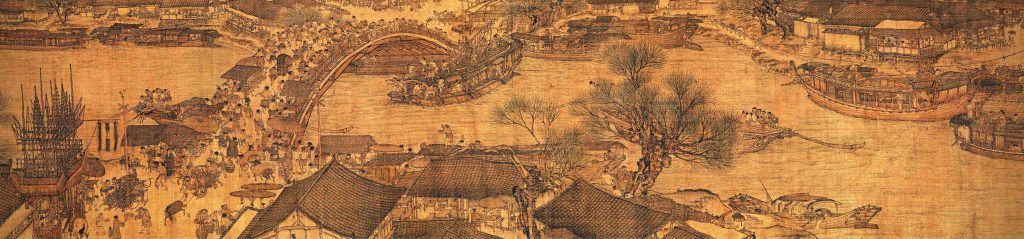

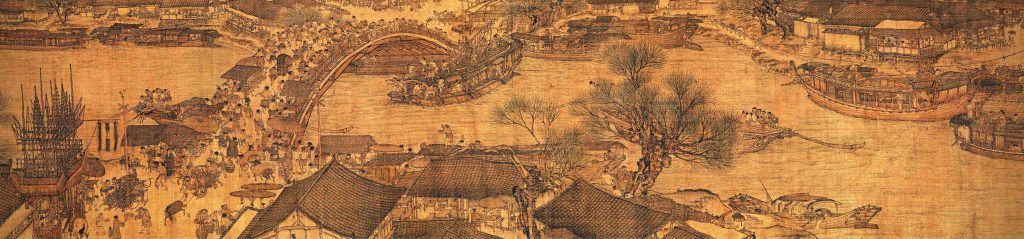

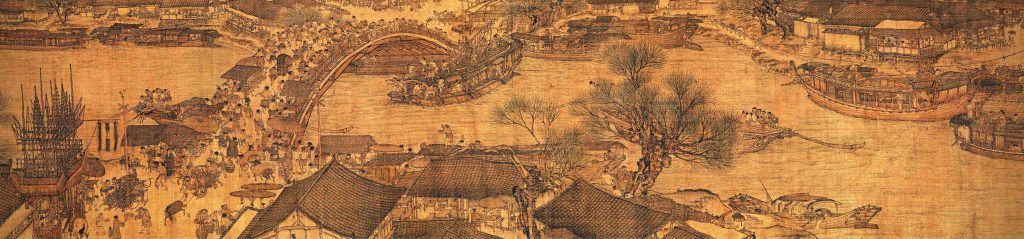

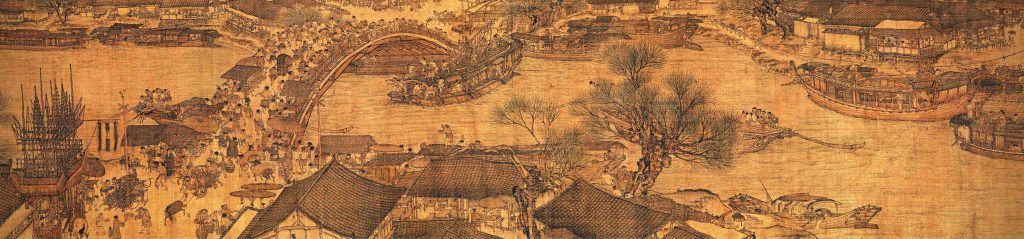

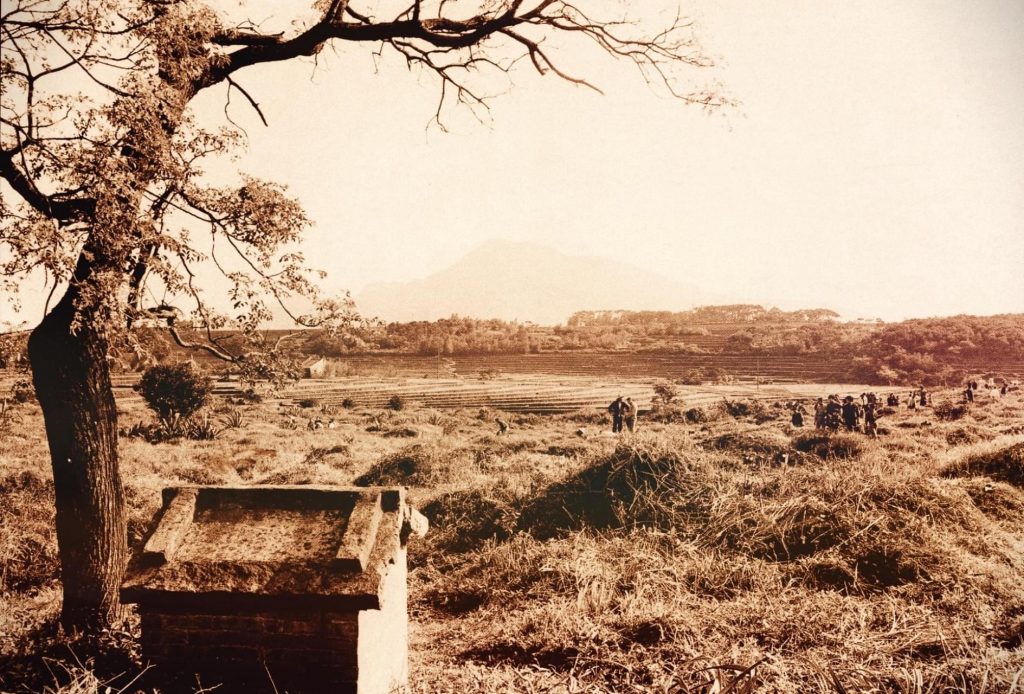

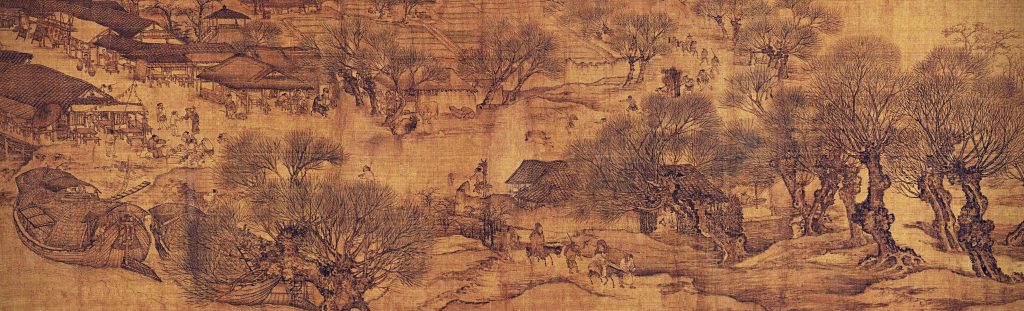

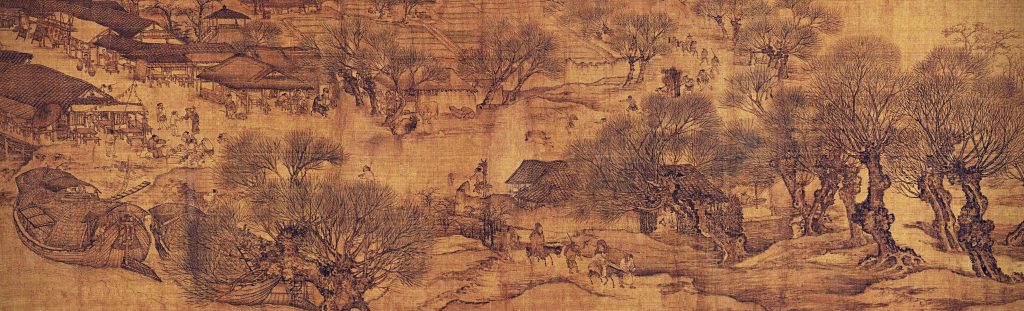

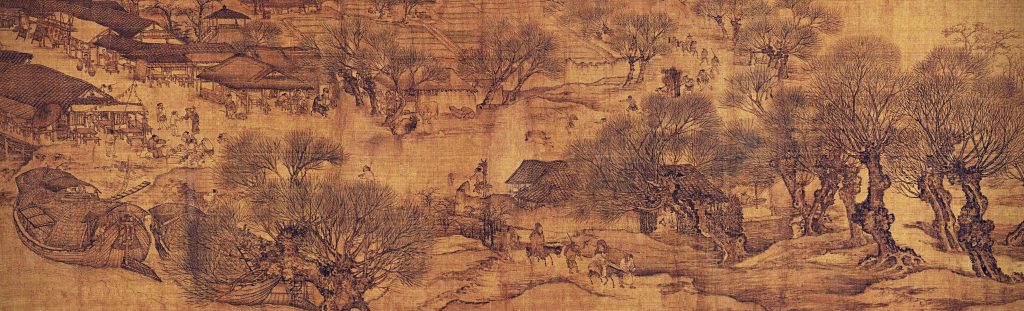

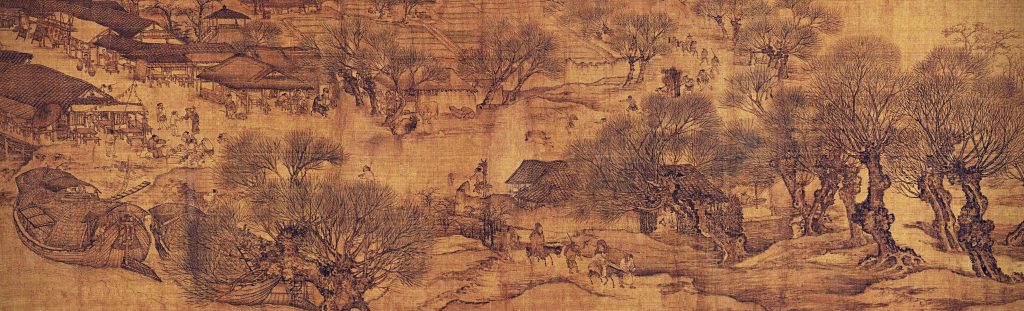

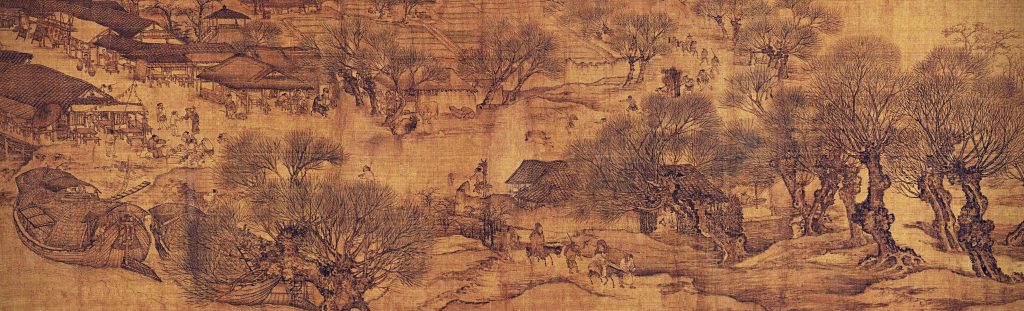

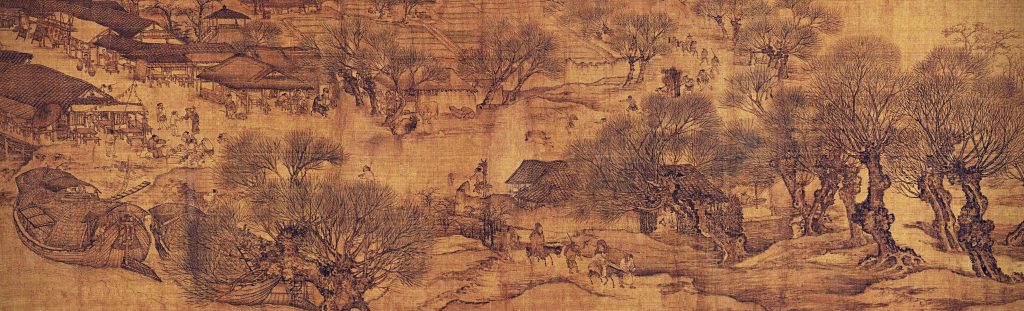

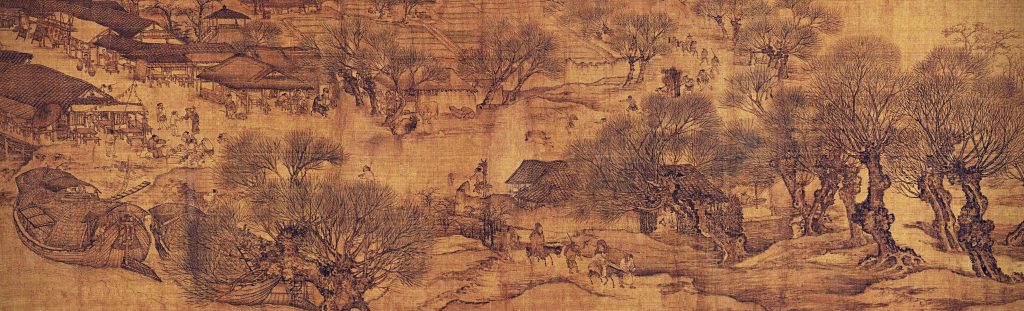

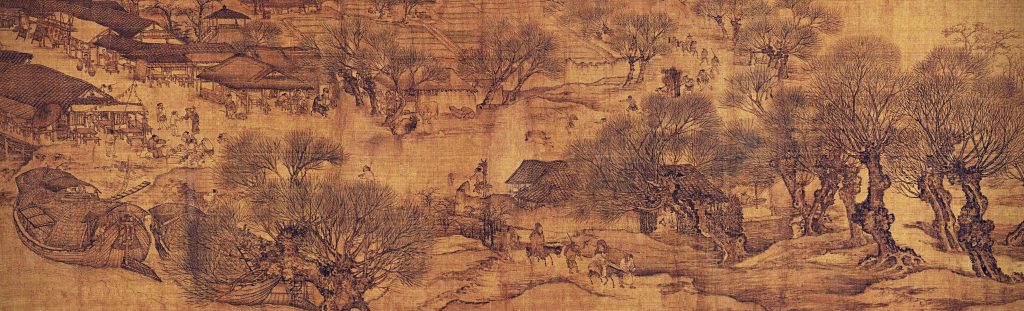

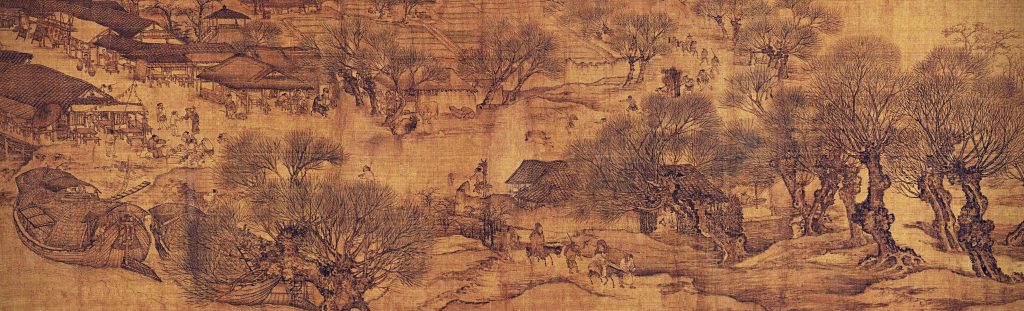

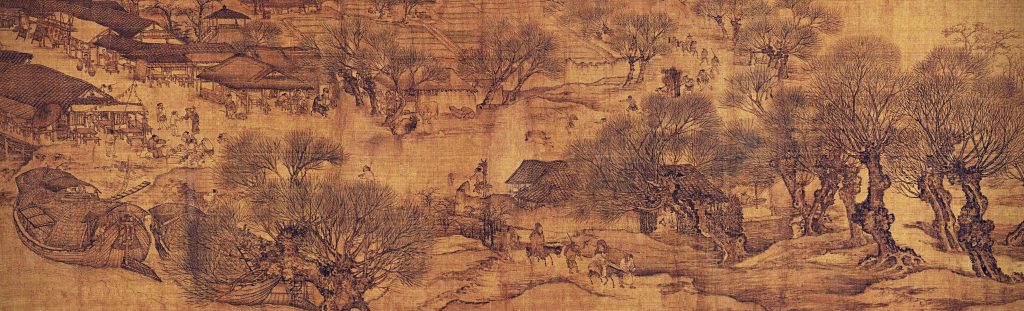

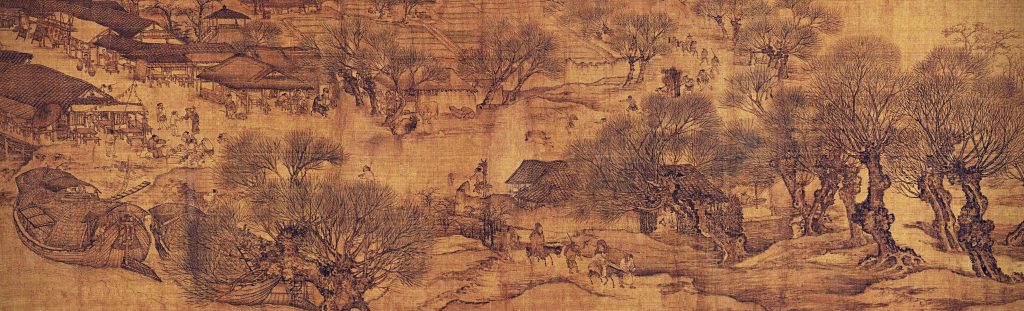

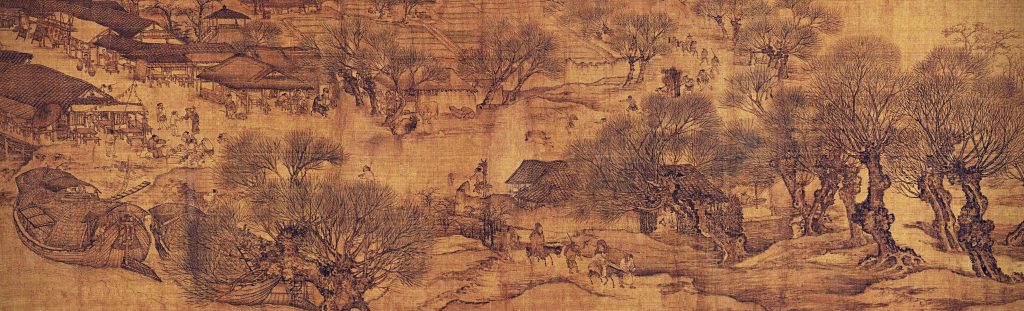

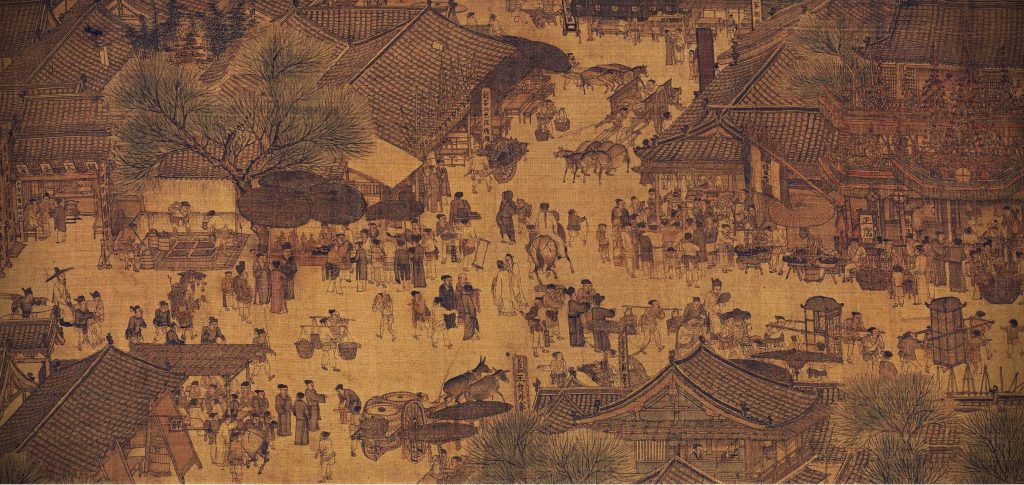

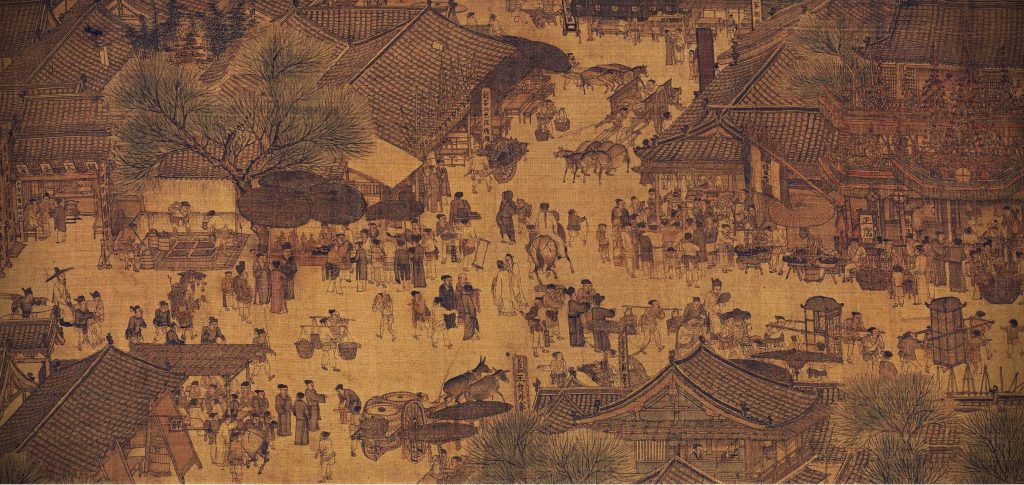

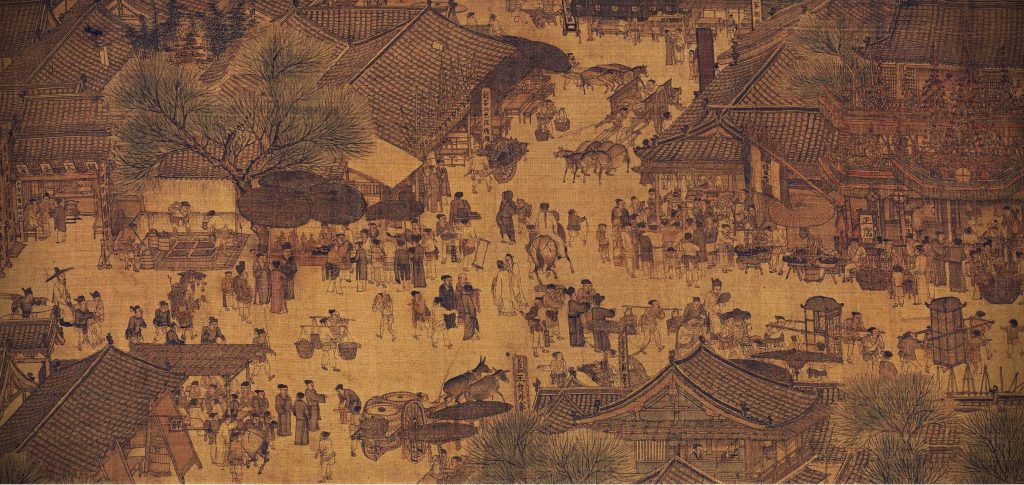

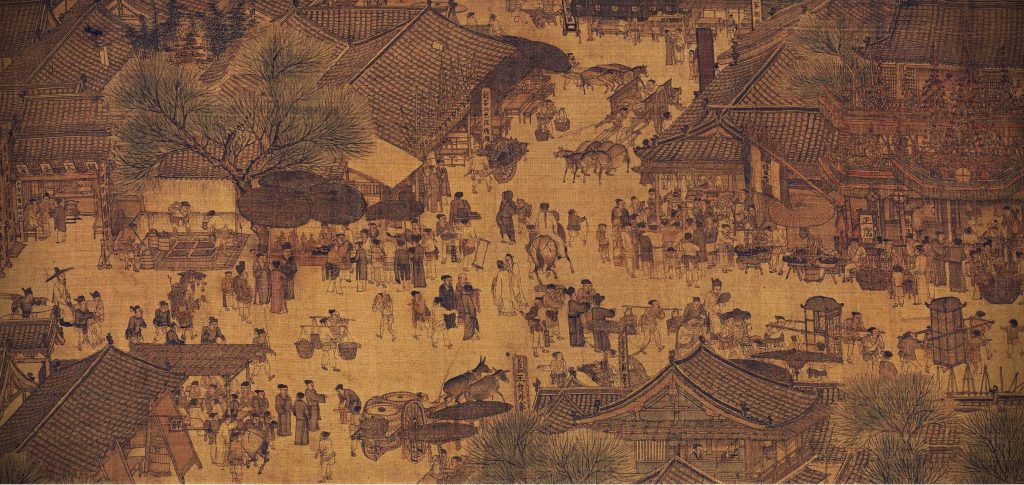

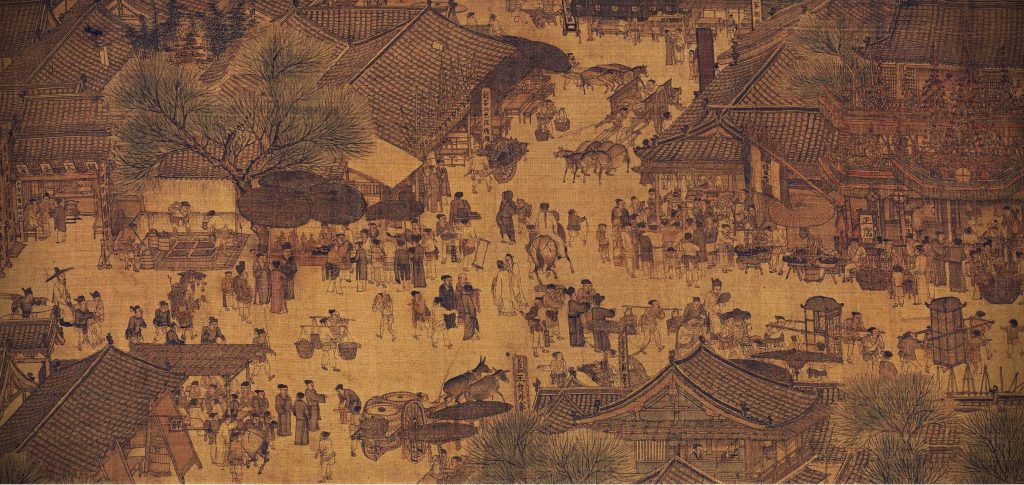

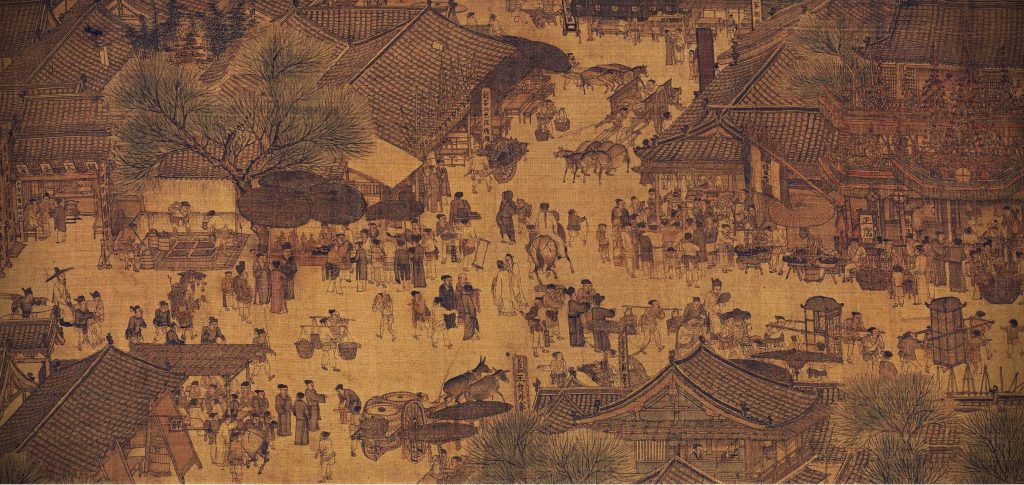

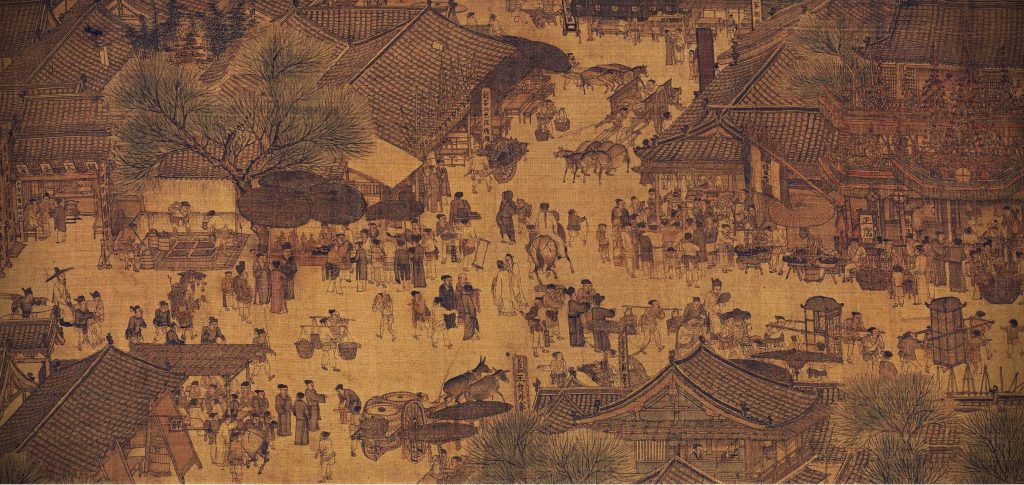

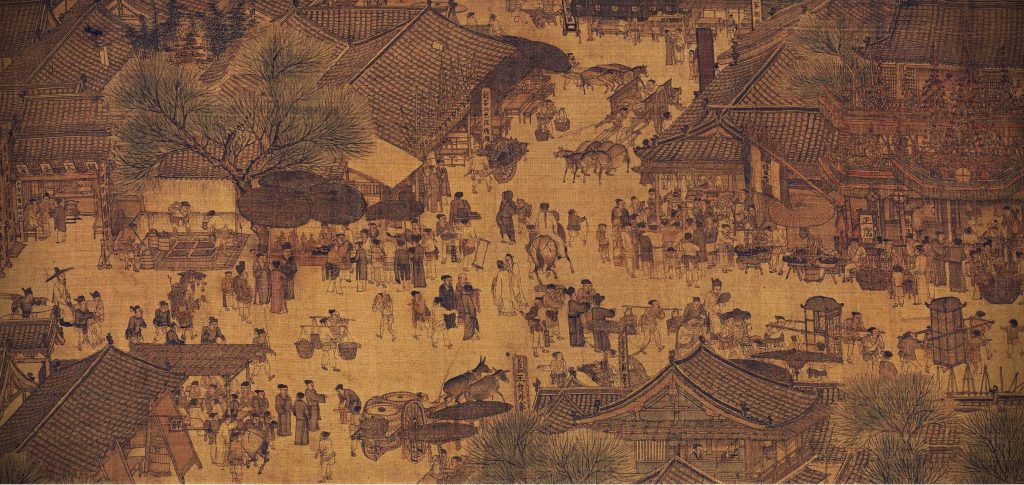

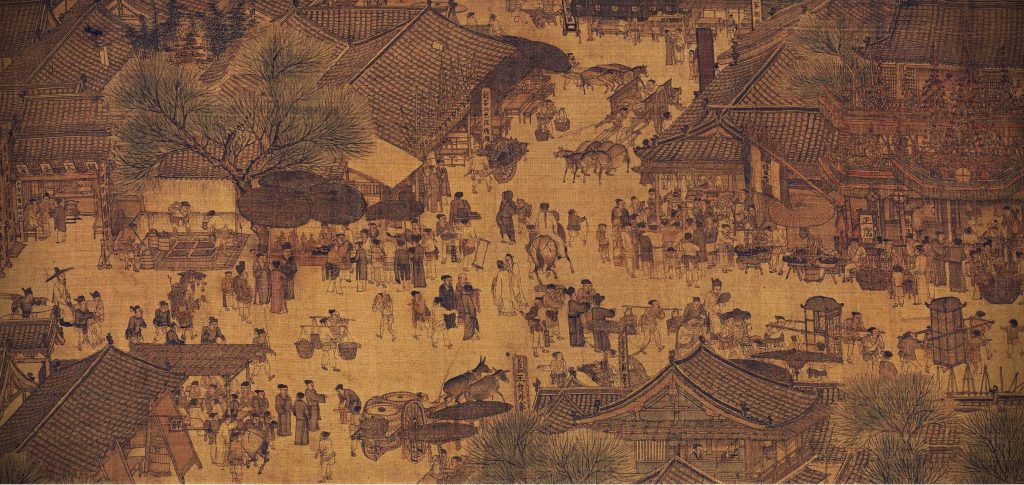

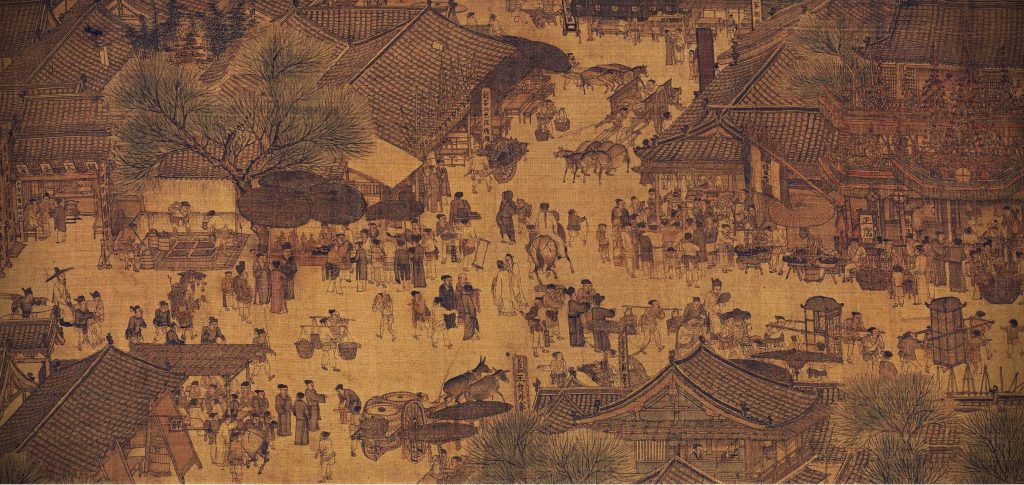

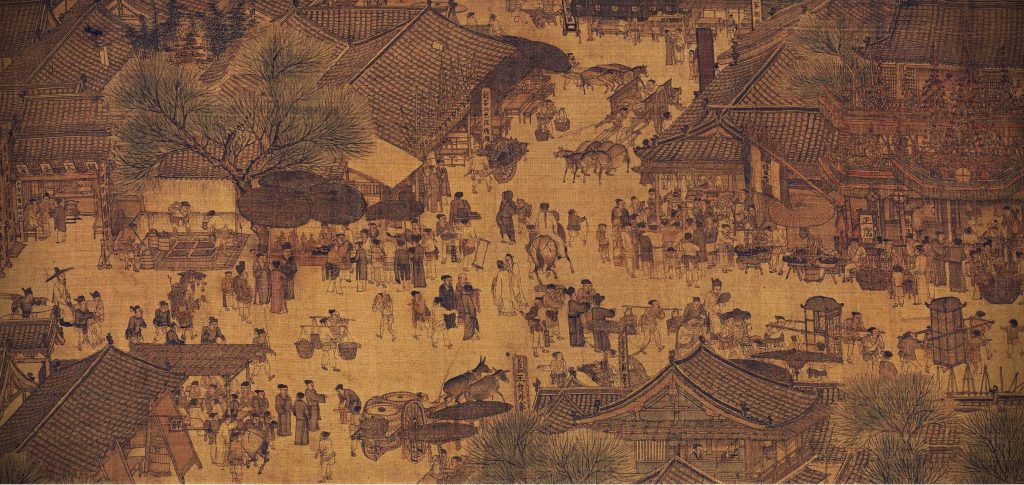

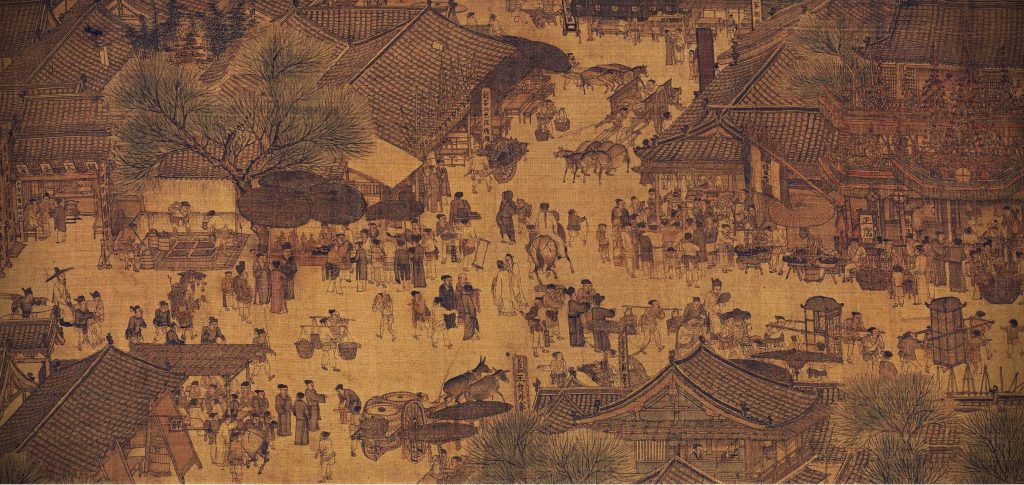

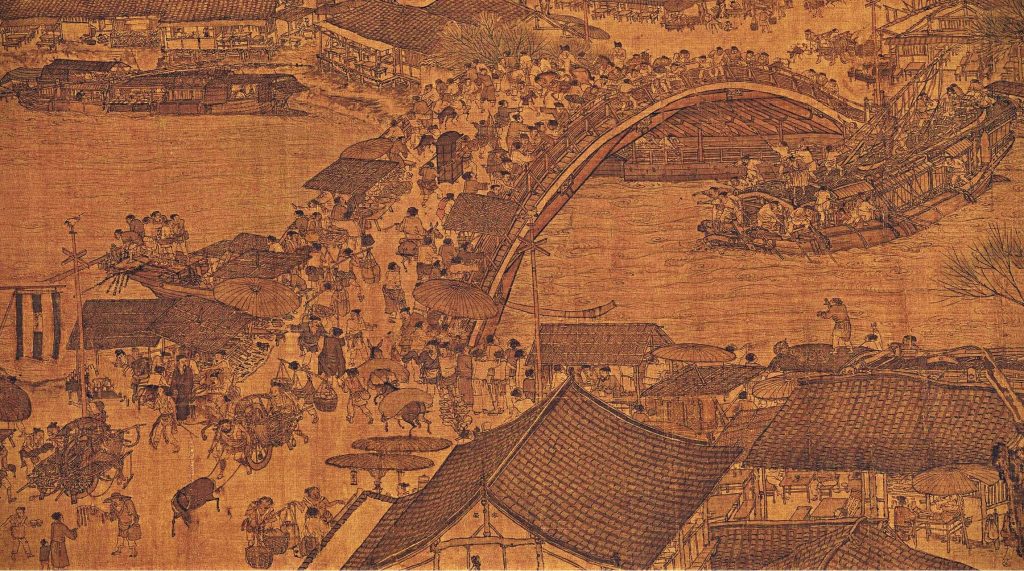

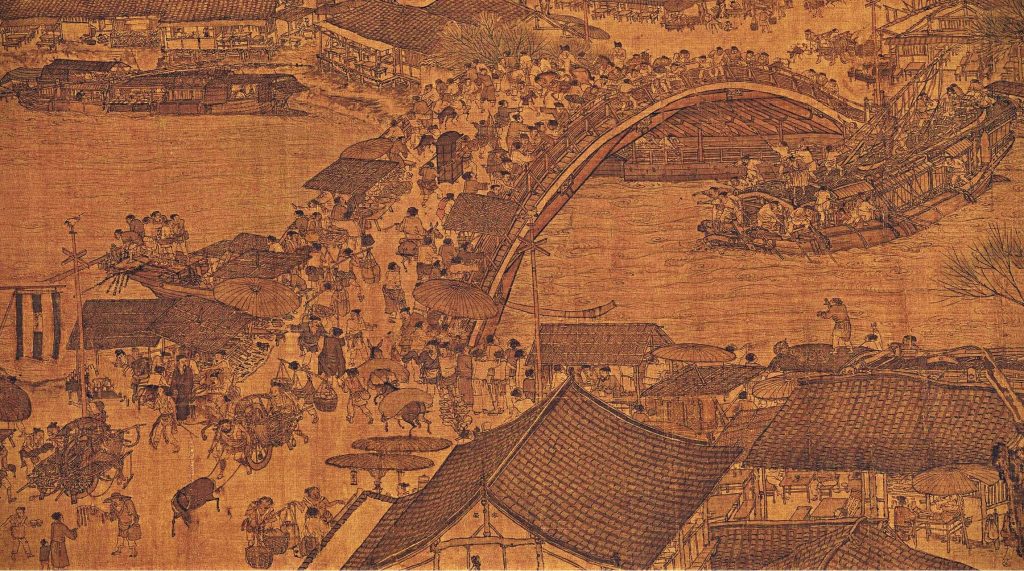

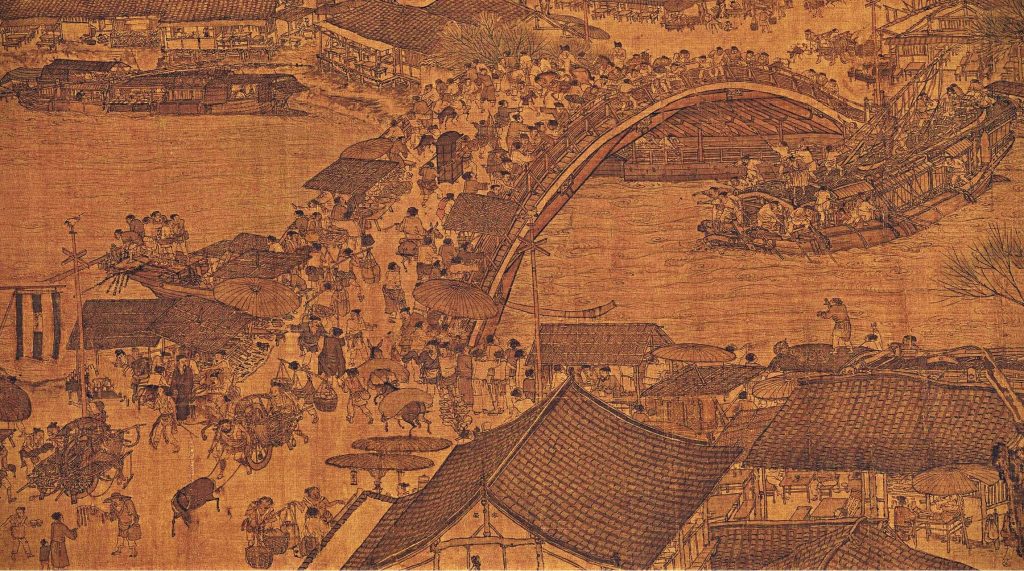

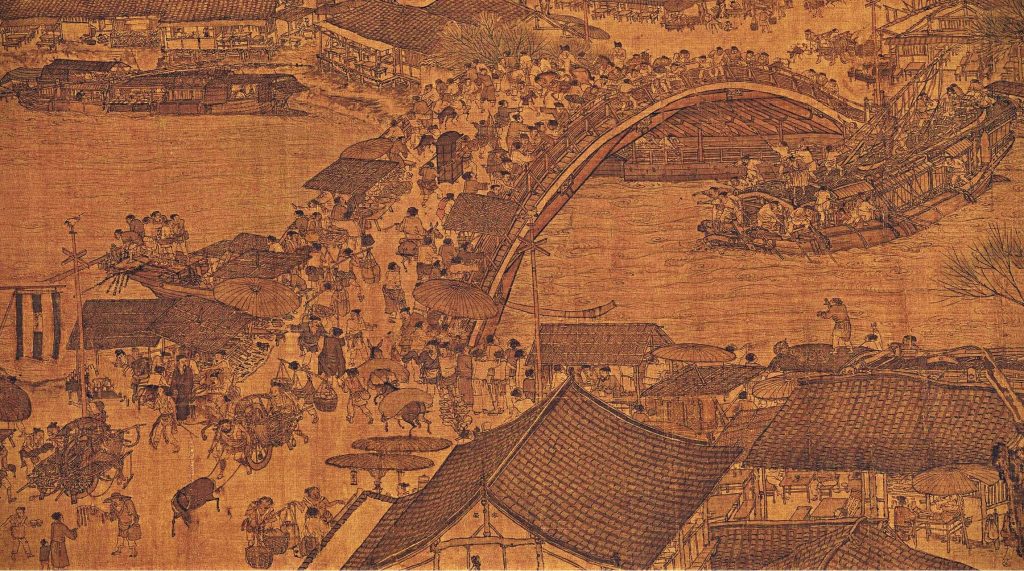

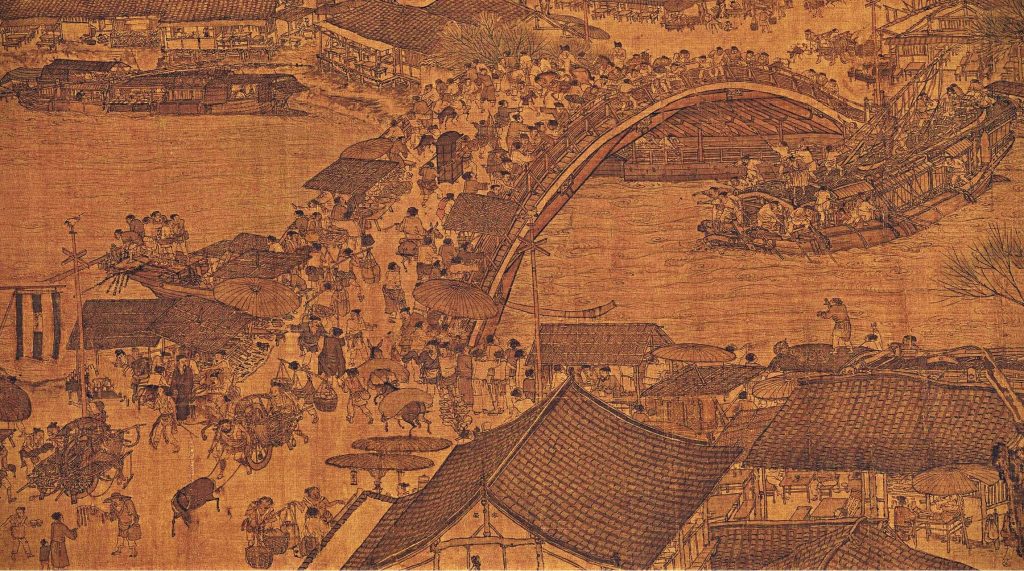

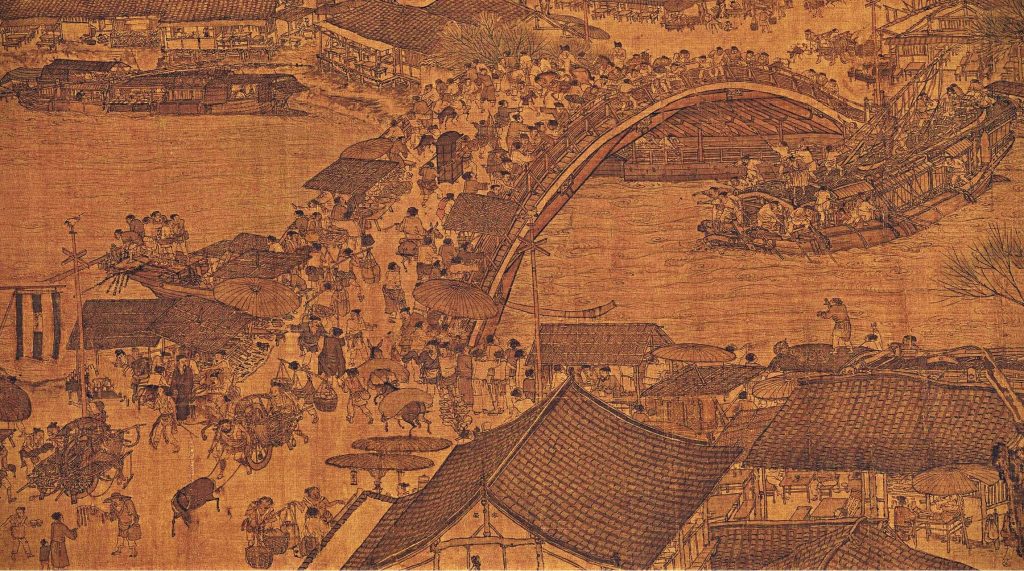

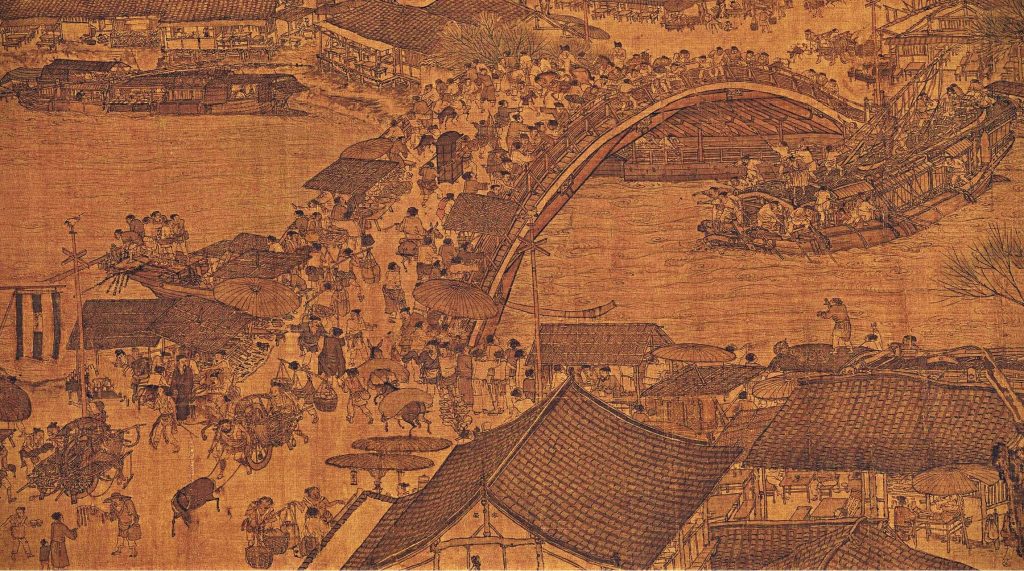

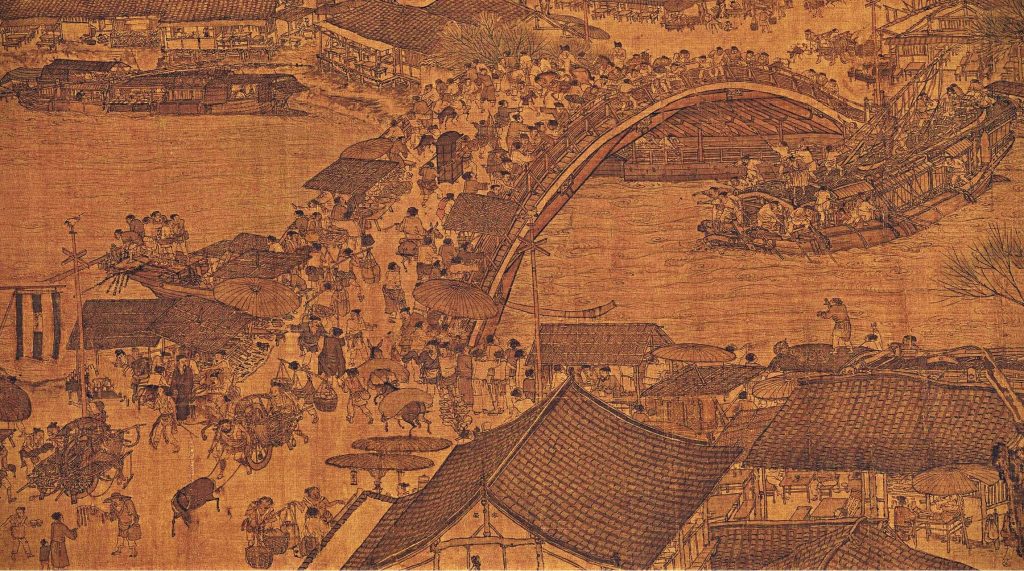

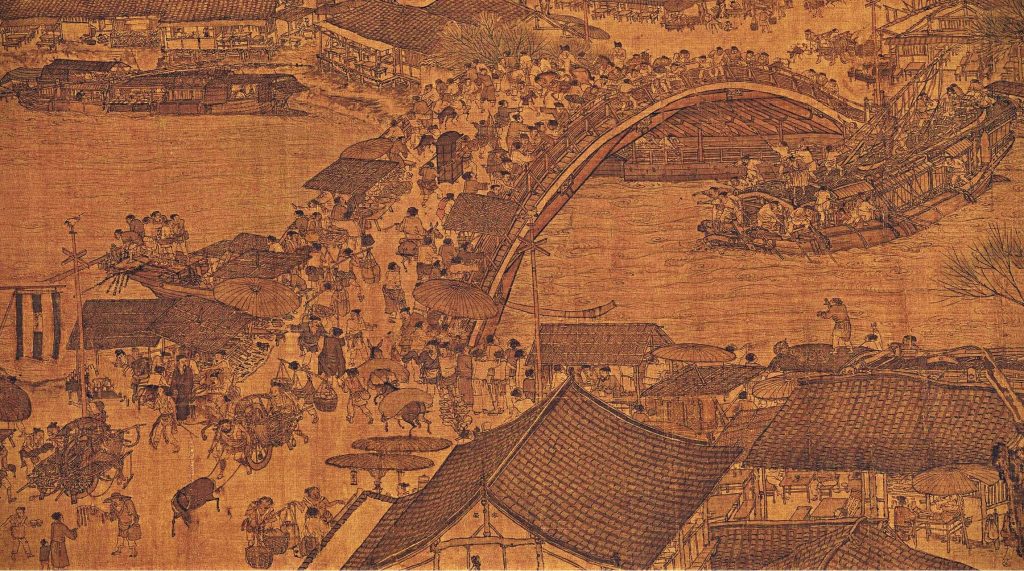

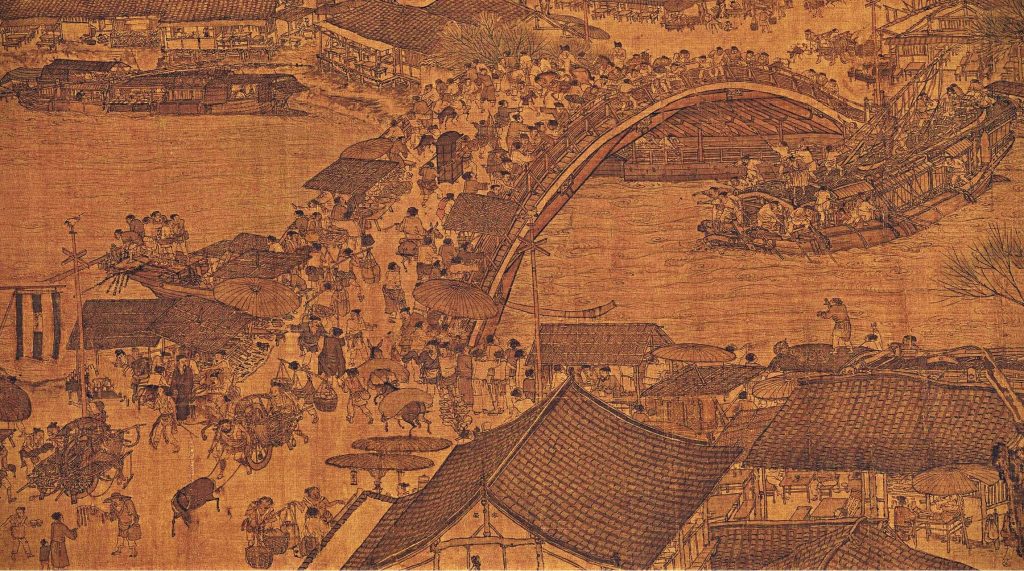

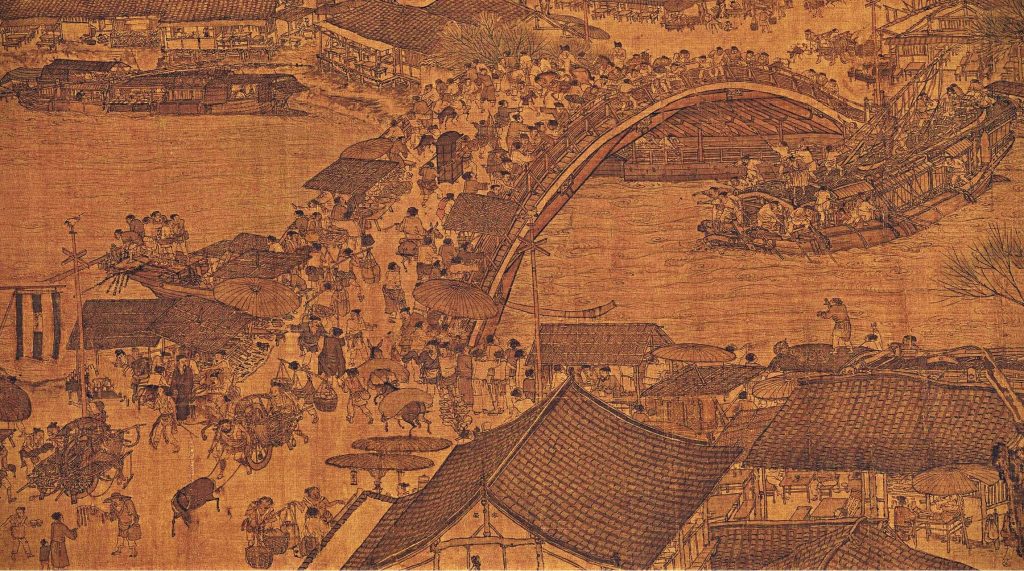

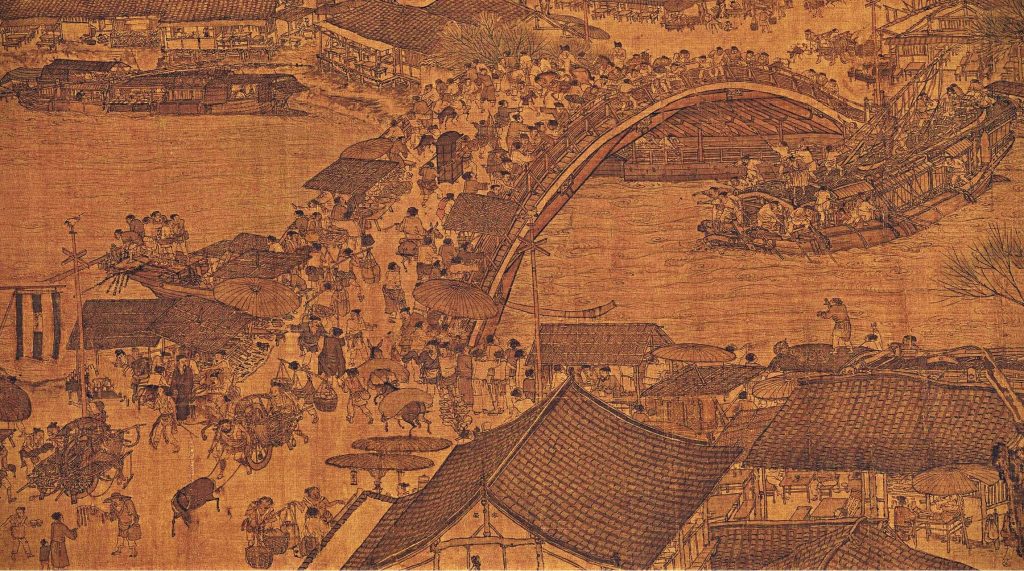

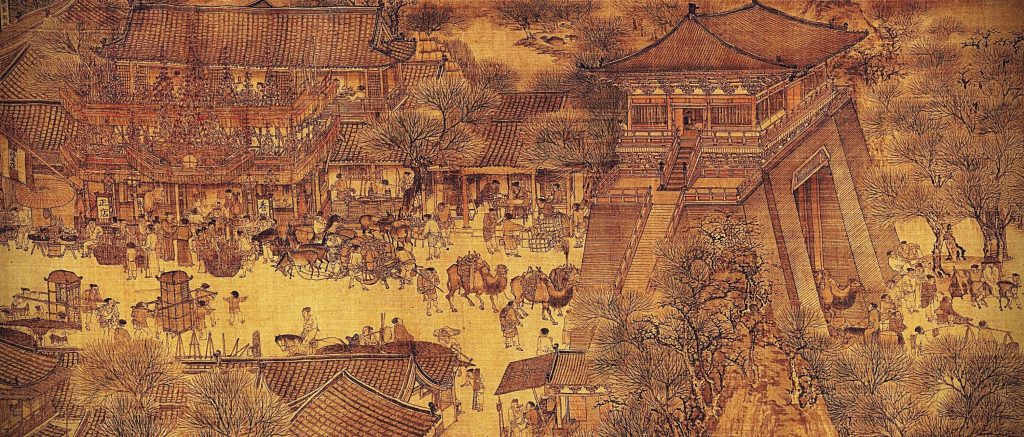

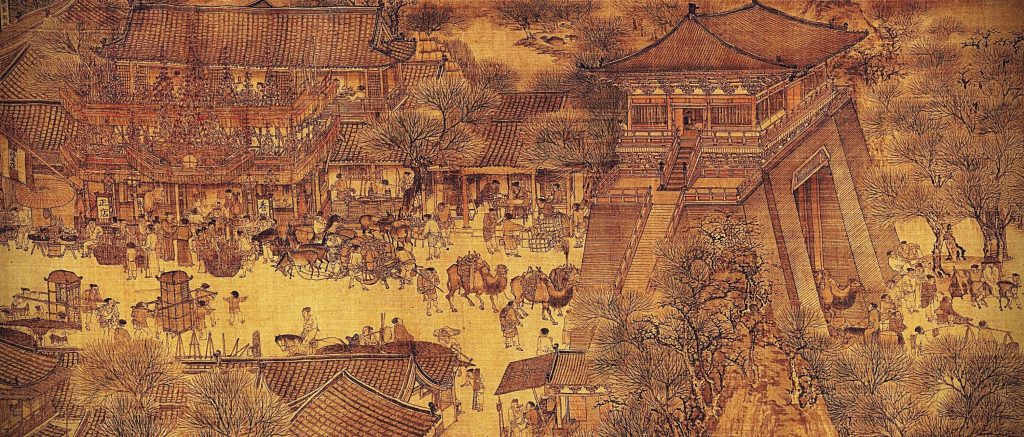

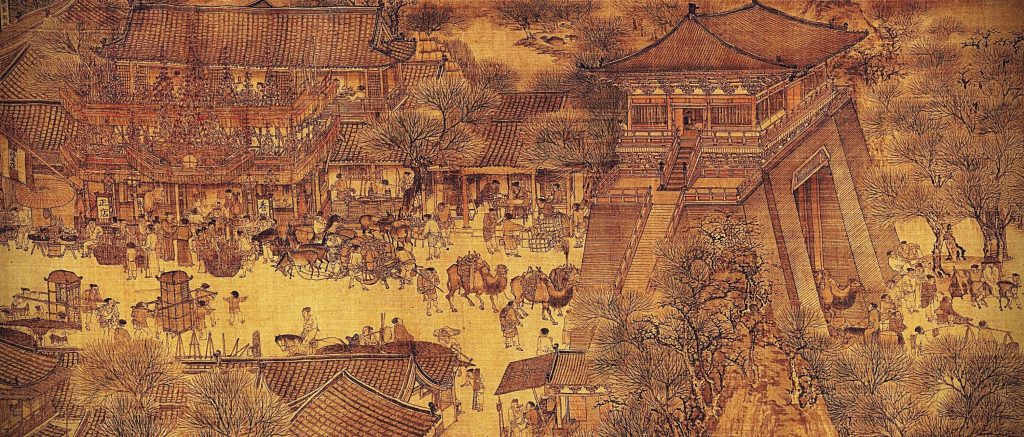

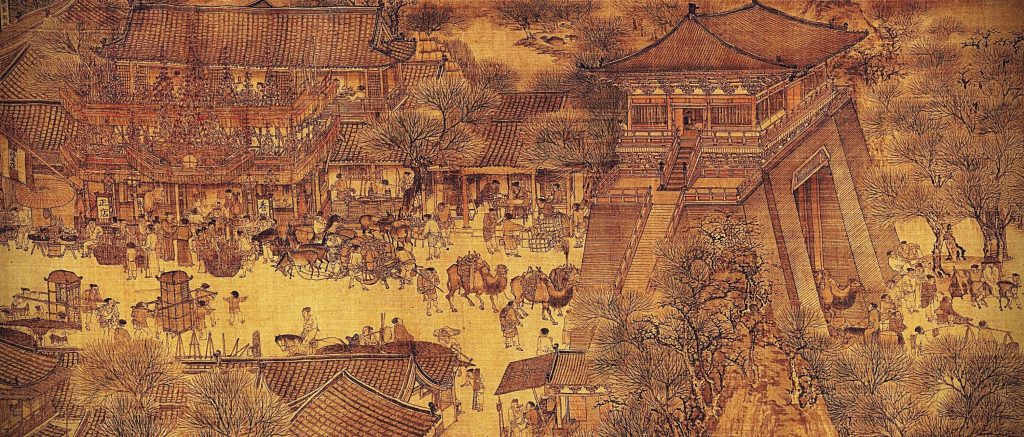

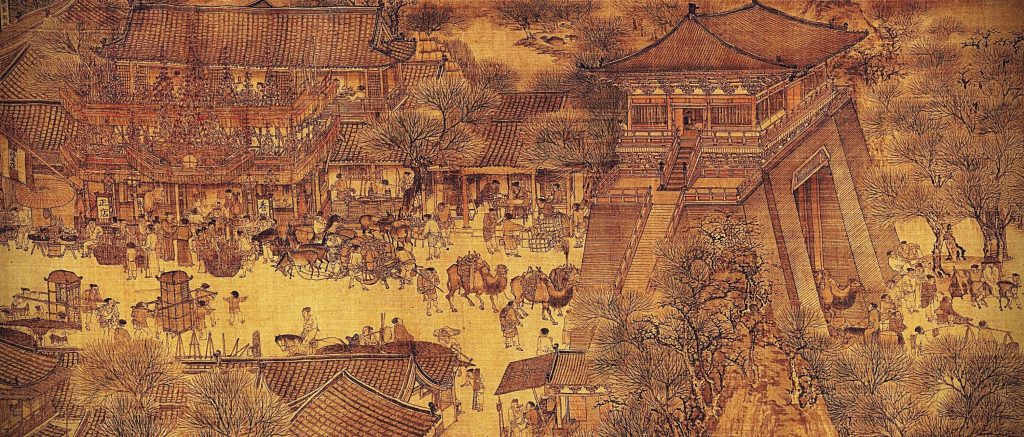

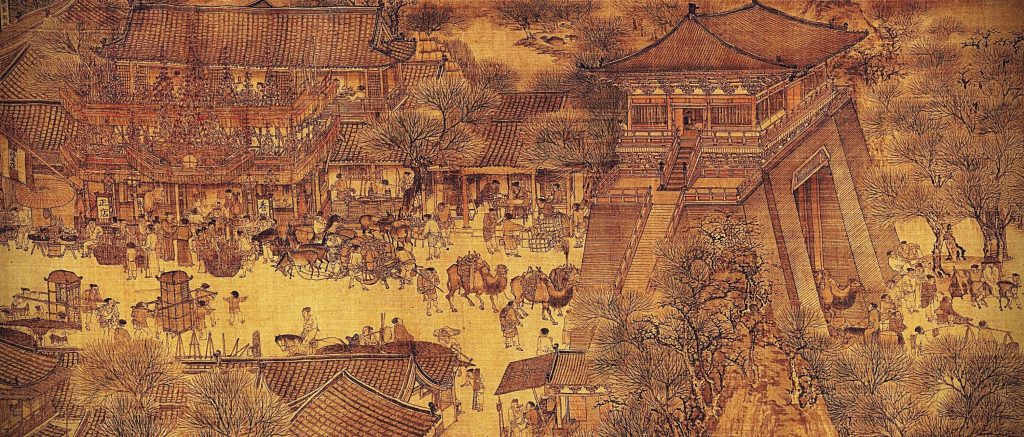

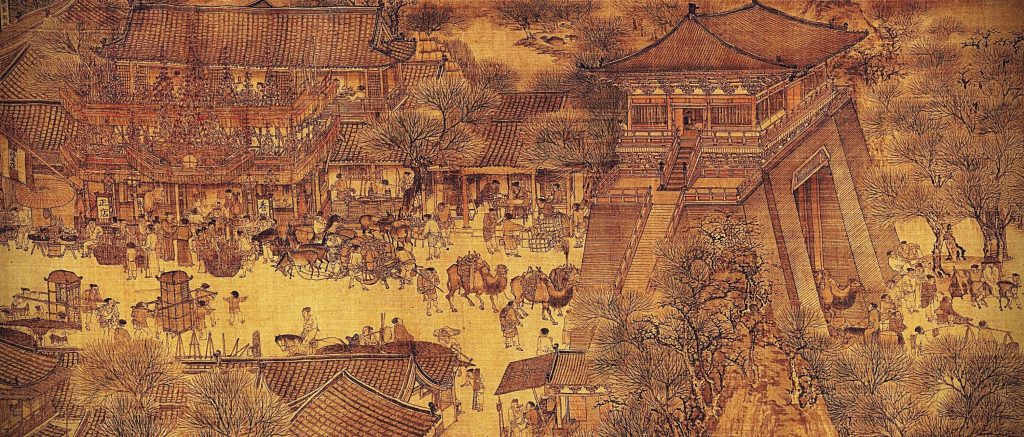

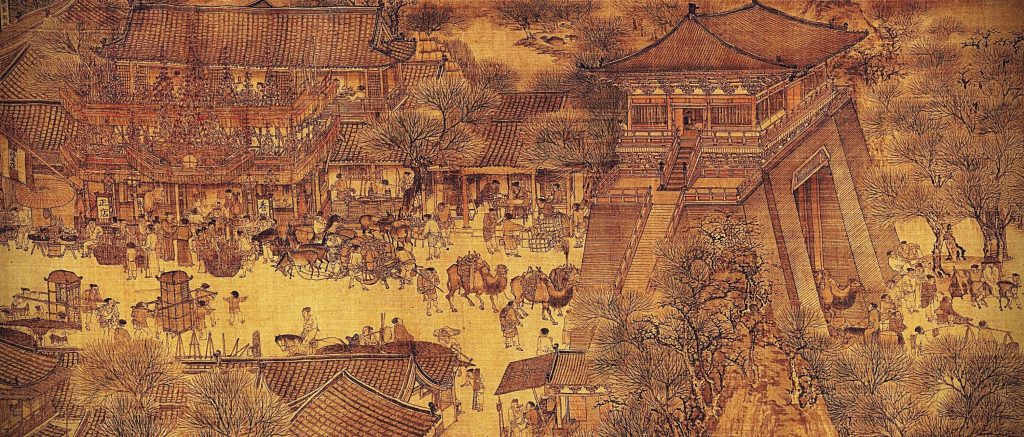

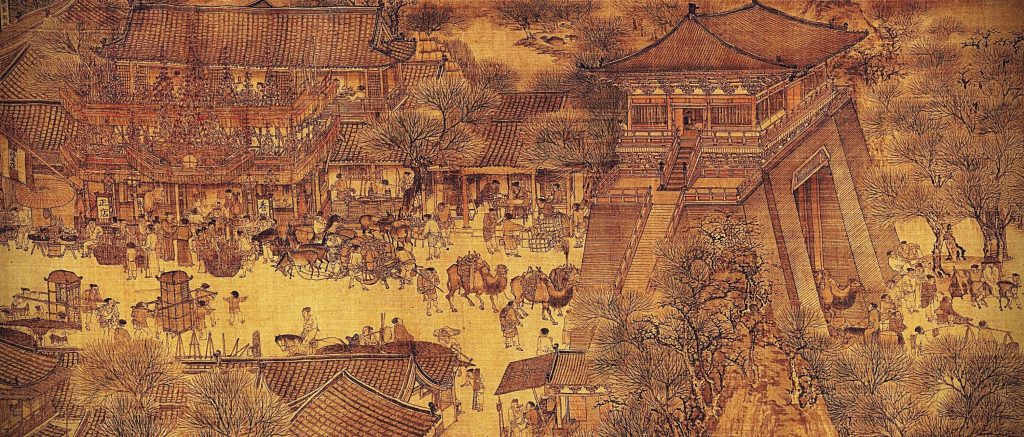

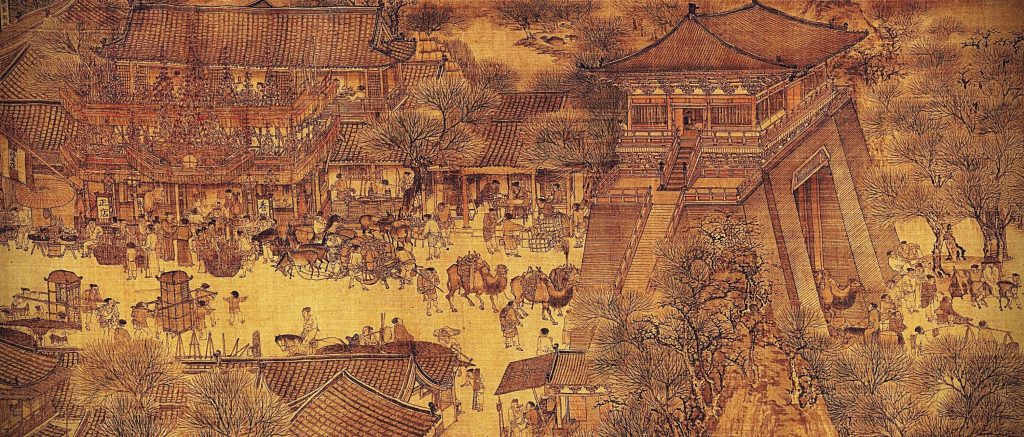

Another artist, Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) also depicted the landscape in his work Along the River During the Qingming Festival. However, instead of concentrating on the vastness of nature, he captured the daily life of the people of Bianjing, present-day Kaifeng. His work reveals much about life in China during the 11-12th century. For example, it depicts one river ship lowering its bipod mast before passing under the prominent bridge of the painting. The myriad of people interacting with one another reveal the nuances of the class structure during the festive days.

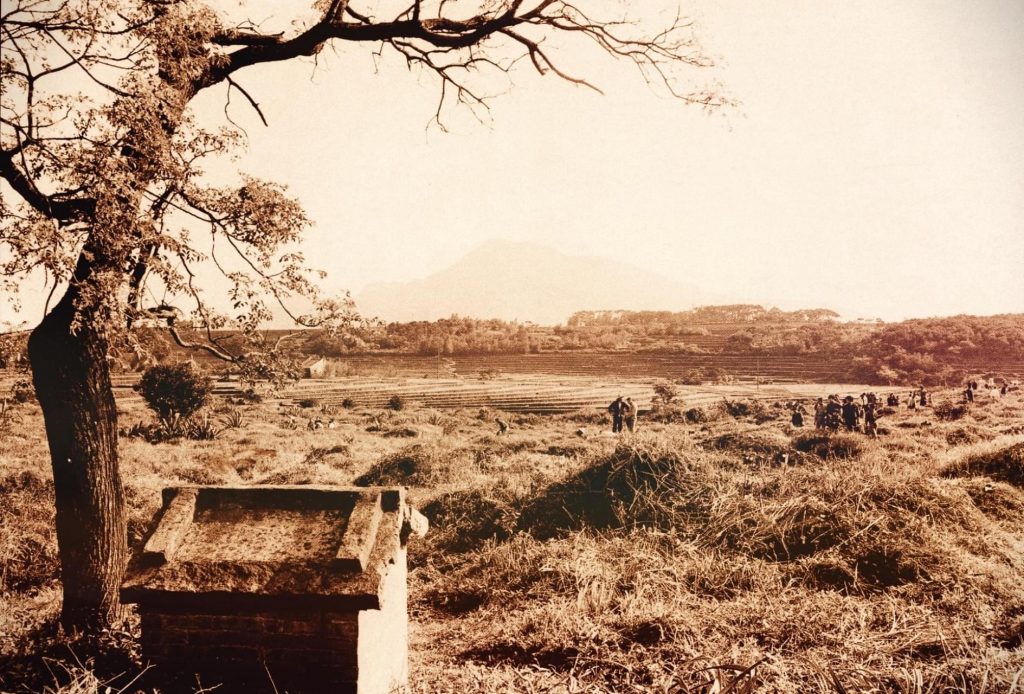

The Qingming Festival has been observed by the Chinese for over 2500 years. During this festival, which takes place between April 4th and 6th every year, Chinese families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean the gravesites. They also pray and make ritual offerings to them. Offerings typically include traditional food dishes and the burning of incense.

Rather than showing ceremonial aspects this painting depicts the festive spirit of the Qingming Festival. Zhang Zeduan portrays the lifestyle of all levels of society from rich to poor. He offers glimpses of period clothing and architecture. Furthermore, the painting is thought to be the most renowned work among all Chinese paintings. It has even been called “China’s Mona Lisa.”

In this five-meter-long scroll, Zhang Zeduan managed to include 814 people, 28 boats, 60 animals, 30 buildings, 20 vehicles, 8 sedan chairs, and 170 trees. There are two main sections of the painting: the countryside and the densely populated city. The right section is the rural area with crop fields, farmers, goatherds, and pig herders. Meanwhile, on the left, urban area, you can see people from walks of life. For example, someone is loading cargo onto a boat, others are begging, and monks asking for alms.

The main focus of the scroll is where the great bridge crosses the river. Vendors extend all along the Rainbow Bridge. You can see the bustling activity with a multitude of people. You wonder if the boat will crash into the bridge as it approaches at an awkward angle with its mast not completely lowered. The crowds on the bridge and along the riverside are gesturing toward the boat.

Because of its skillful representation of life in the Song dynasty (960–1279), this painting has been imitated, copied, and forged many times. The story has it that Qiu Ying, a 16th-century artist who painted beautiful copies of Along the River During the Qingming Festival, prompted forgers to produce forgeries of his copies.

The painting has been treasured so much that the Qianlong Emperor may have composed the following poem on the Qing copy of the painting:

The bustling scene is truly impressive.

It is a chance to explore vestiges of bygone days.

At that time, people marveled at the size of Yu,

And now, we lament the fates of Hui and Qin.The poem on the copy of the painting, Qianlong Emperor, 1742.

Some people believe that this painting was created as the artist’s message to the emperor to discern dangerous trends beneath the surface of prosperity. You can observe that few guards stationed at the city gate and the docks appeared not to be alert. The name of the painting could also be ironic and refer to a bright and enlightened era instead of the festival.

Nevertheless, the work became so famous that artists created a 3D animated, digital version of the painting called The River of Wisdom. It is roughly 30 times the size of the original scroll. The computer-animated mural has moving characters and objects and portrays the scene in four-minute day and night cycles. Today, the animation is on permanent exhibition at the China Art Museum, Shanghai.

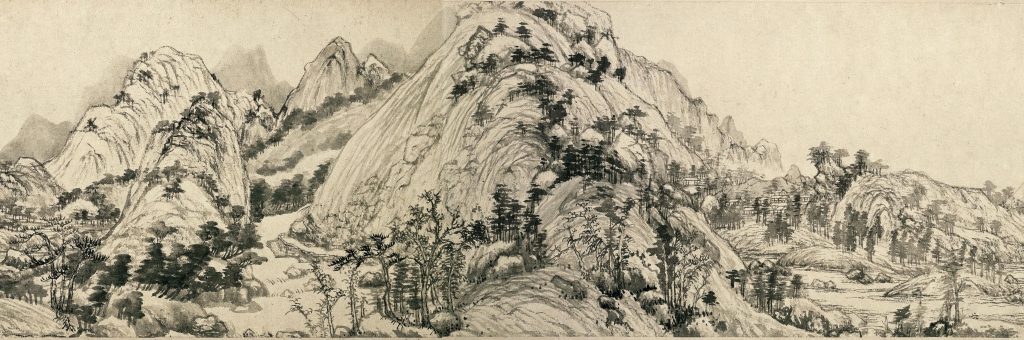

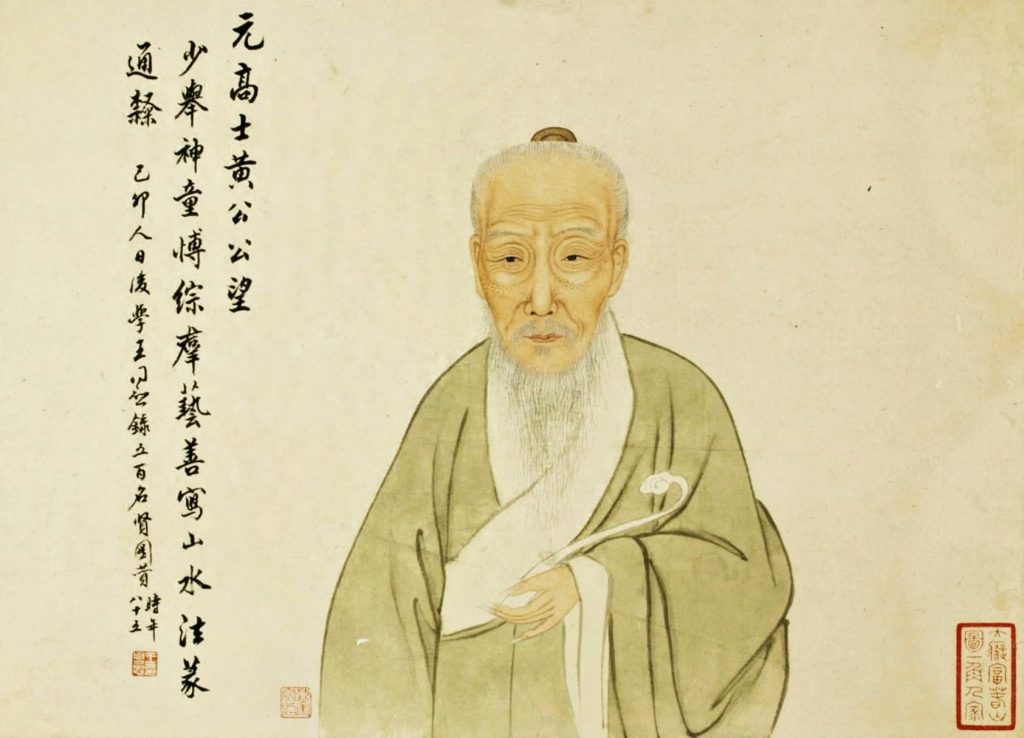

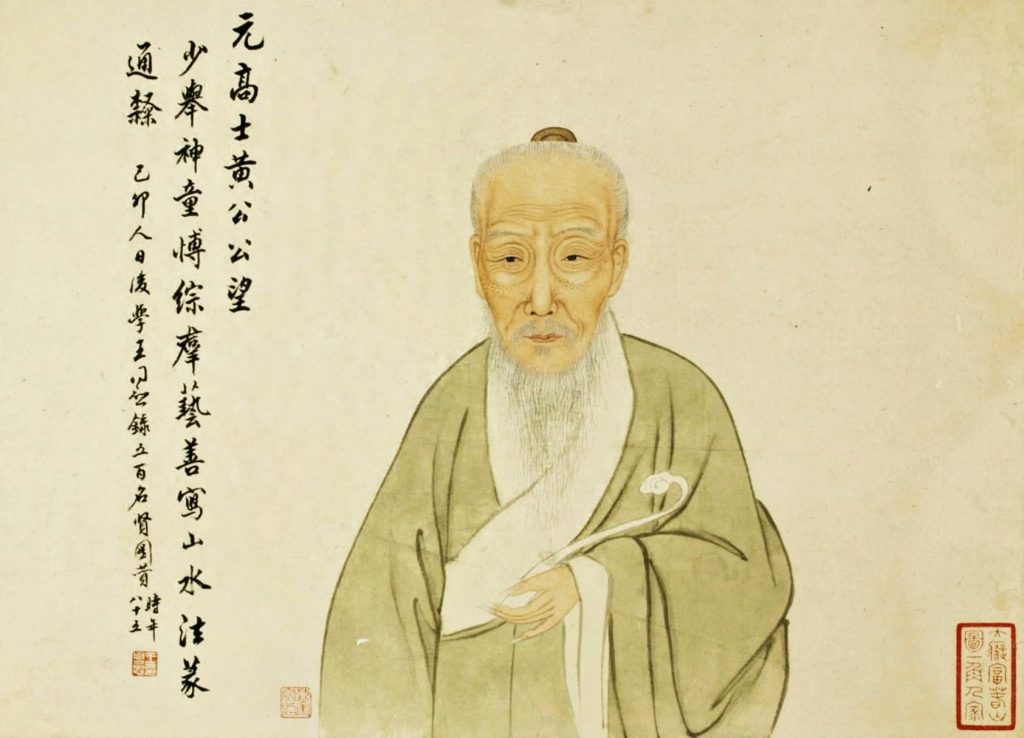

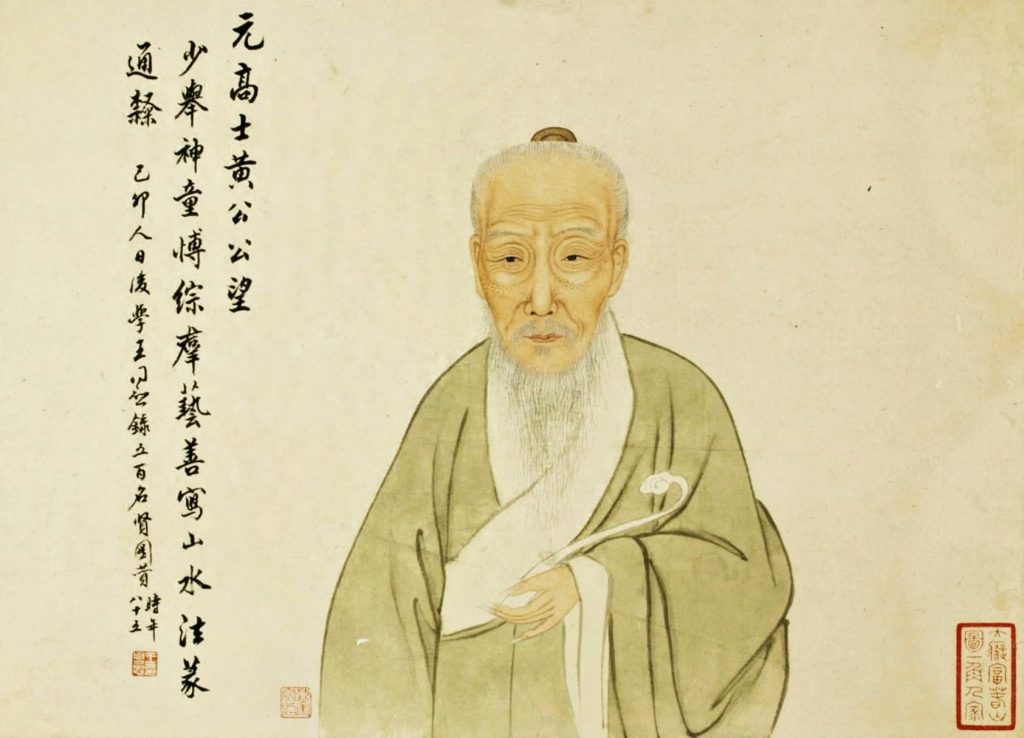

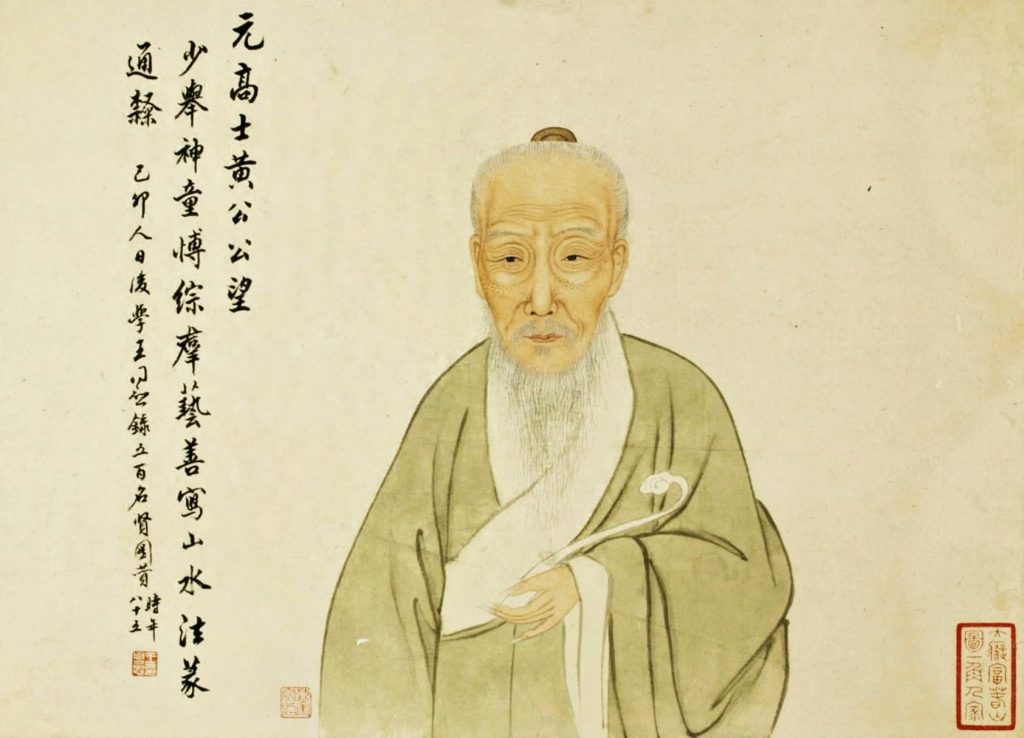

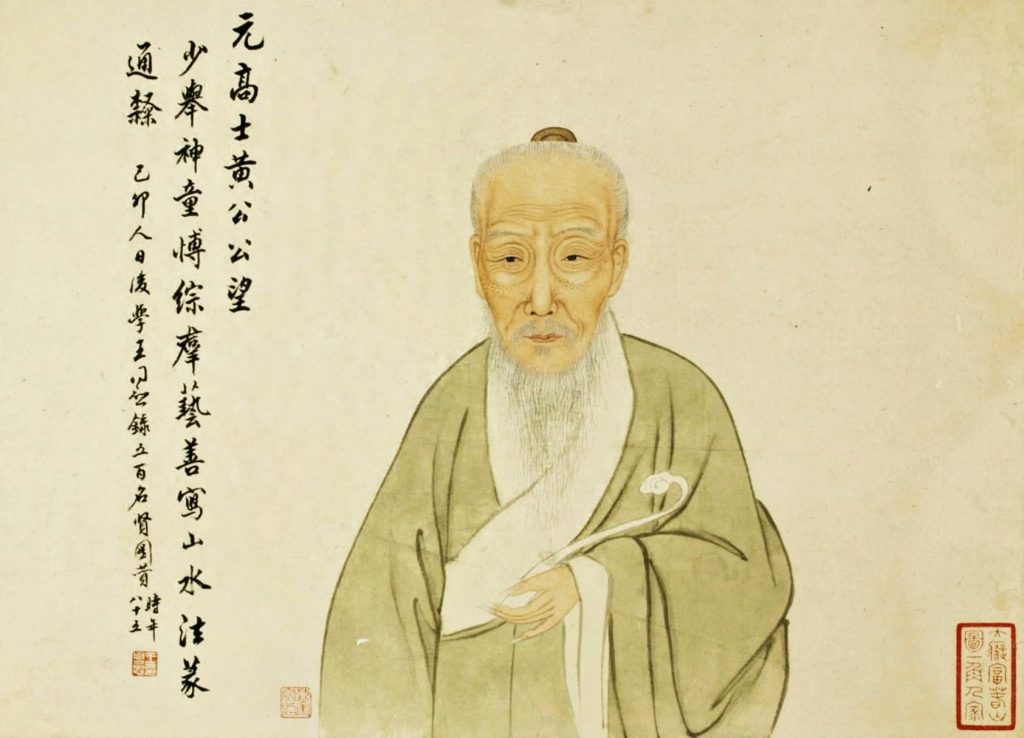

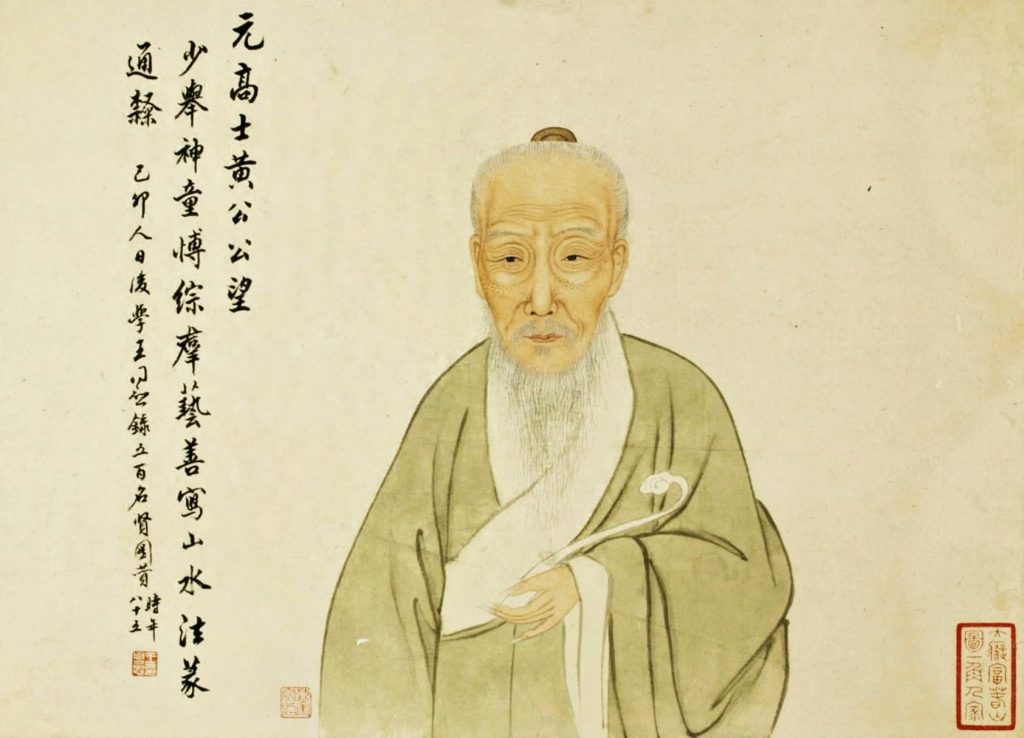

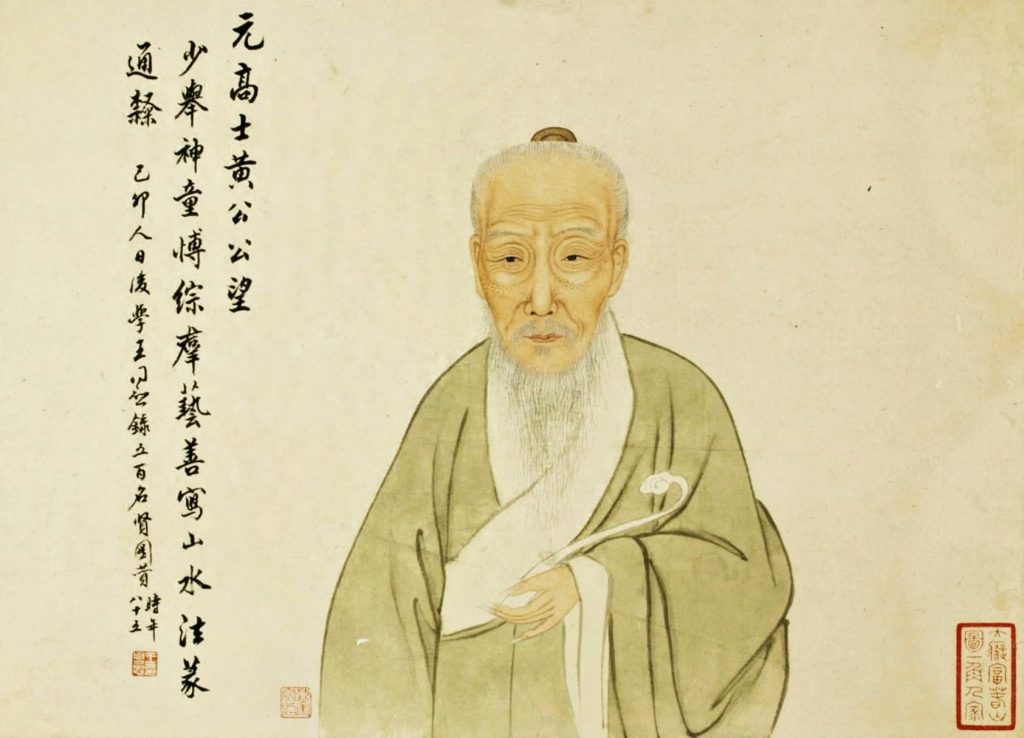

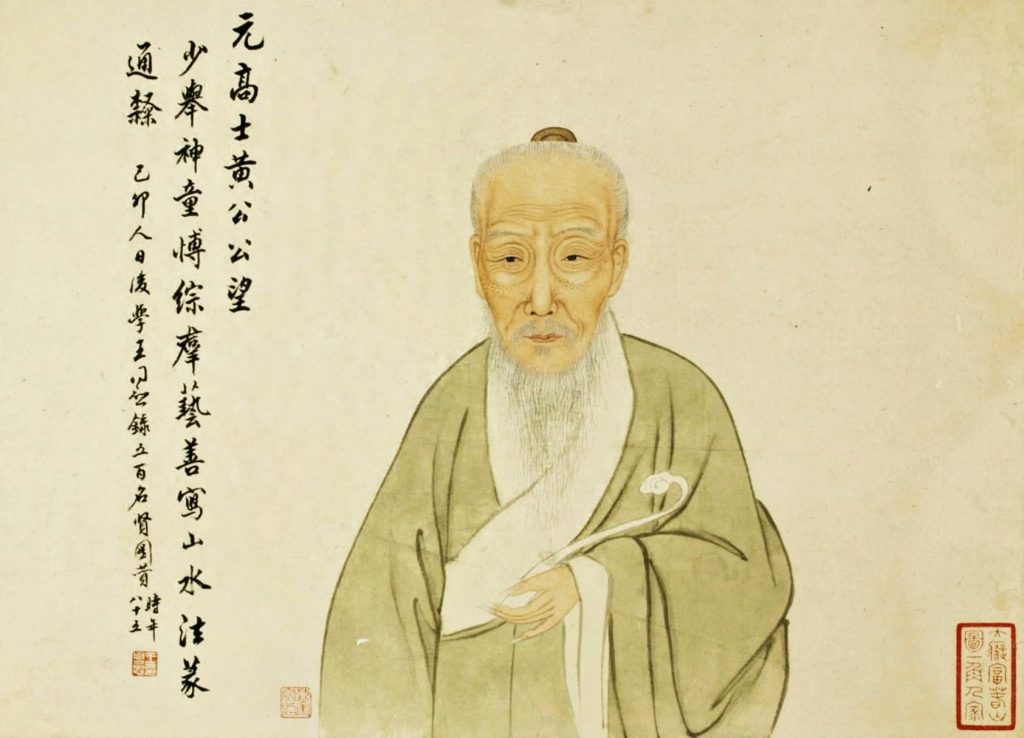

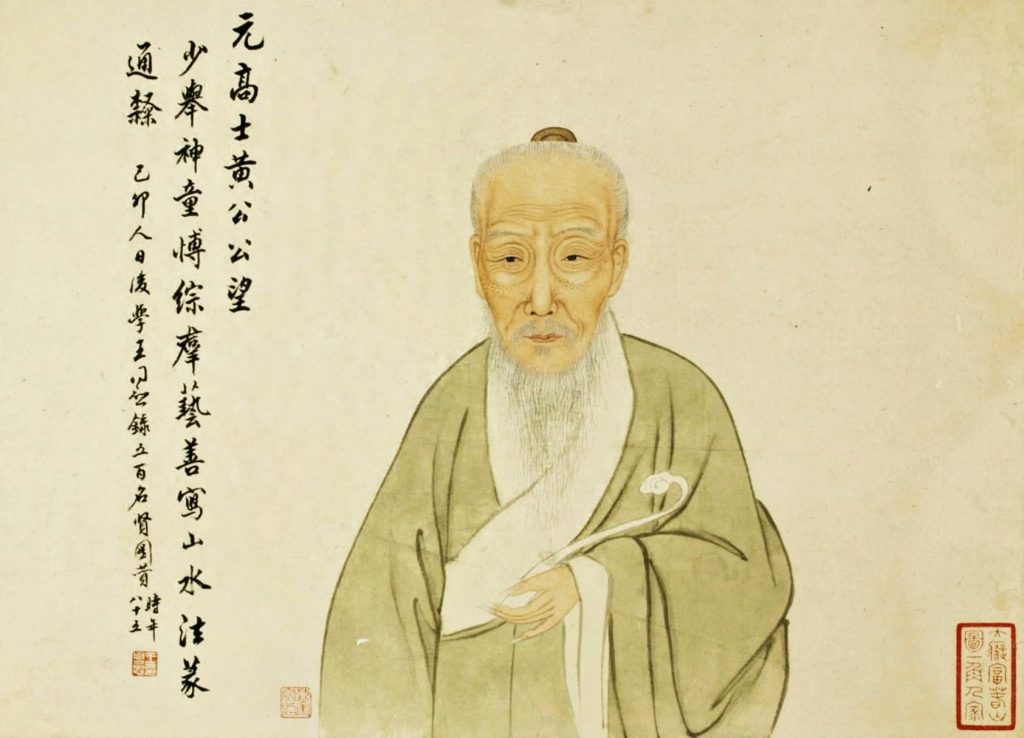

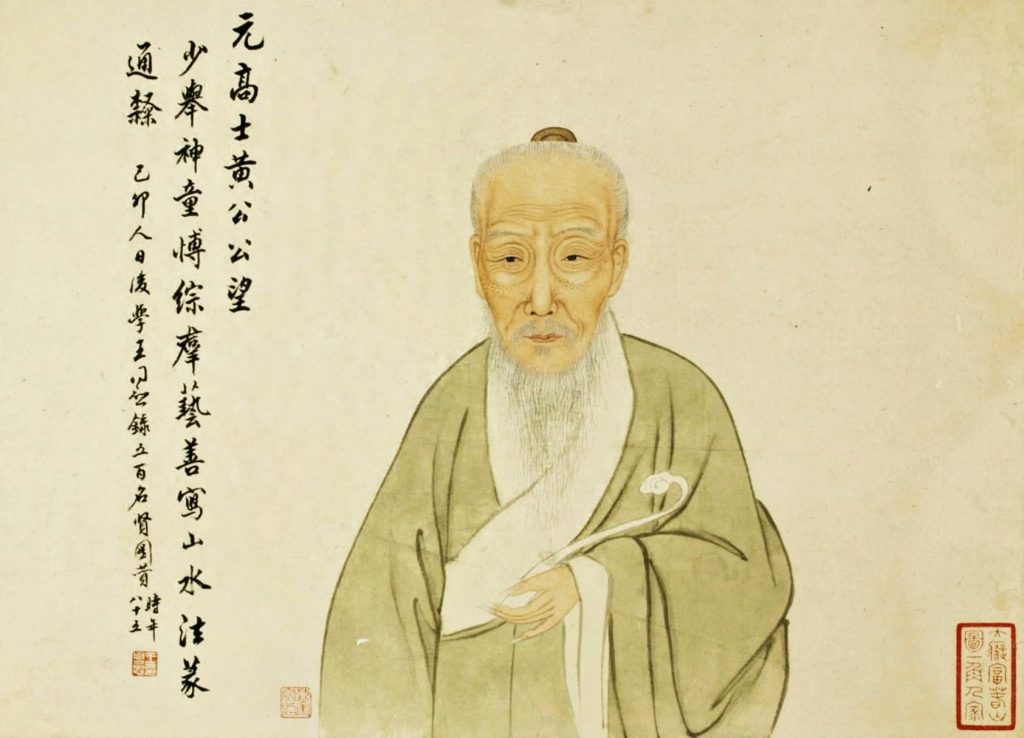

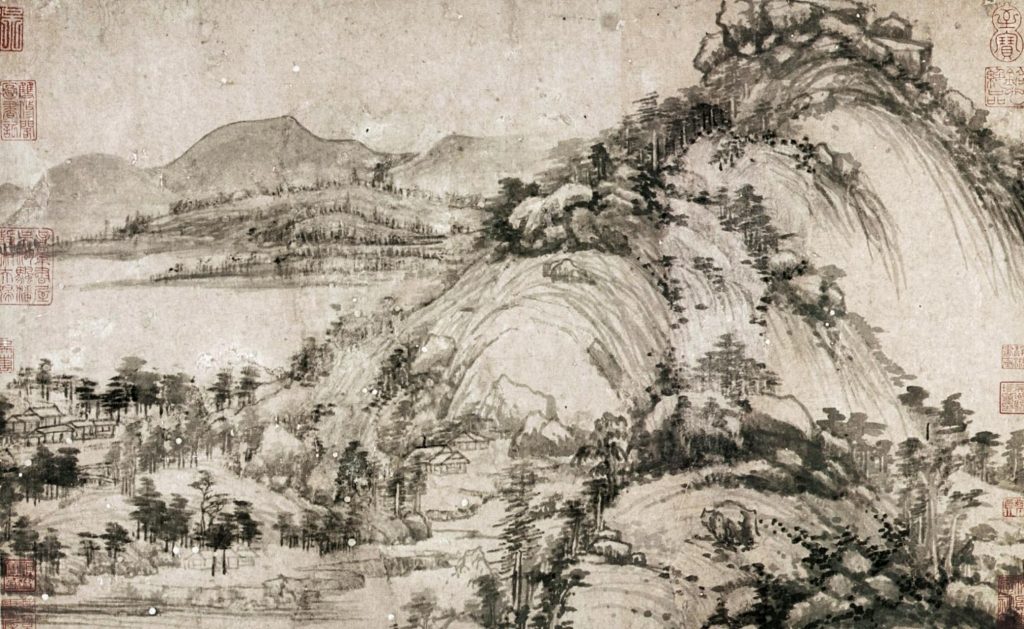

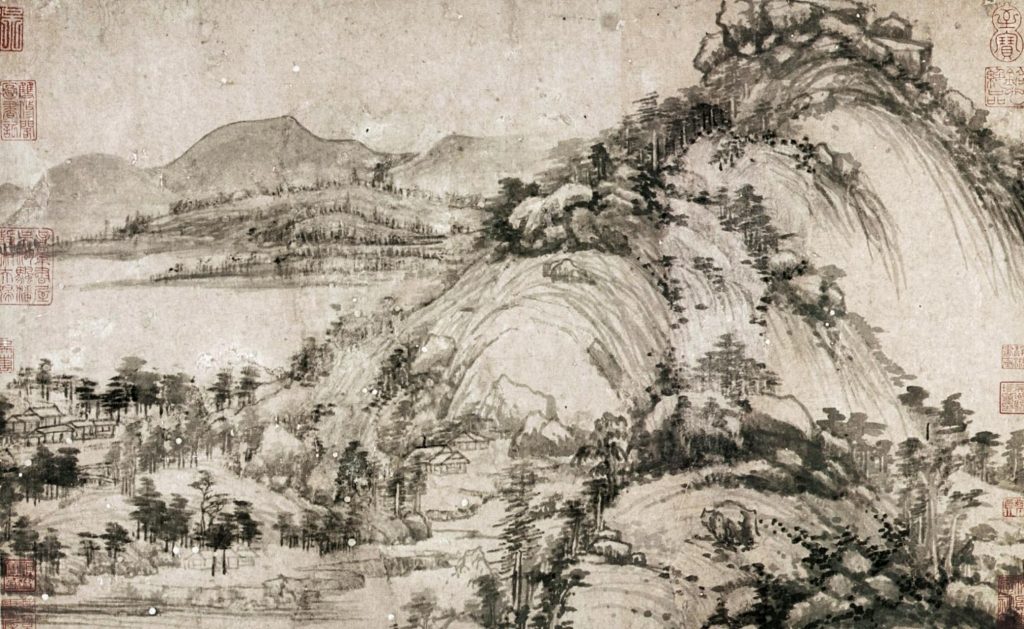

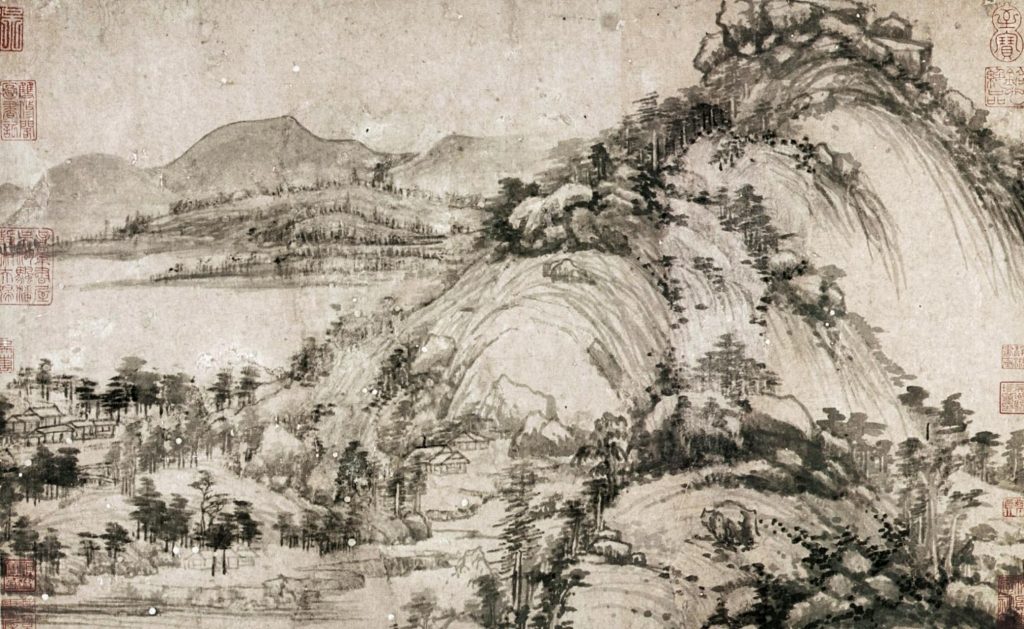

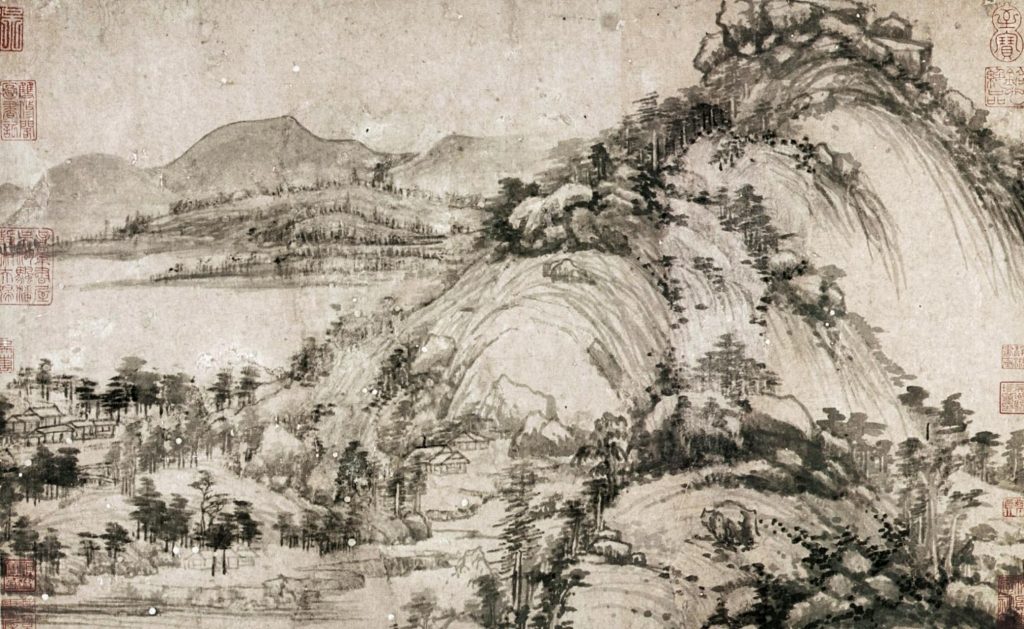

Huang Gongwang (1269–1354) was only 10 years old when the Song Dynasty fell to the Yuan Dynasty. Therefore, many painters openly opposed official tendencies in art. They did not want to live in the capital and work at the Mongolian court. In their paintings, these artists turned to the themes developed in the Song dynasty, such as retreat into nature.

Like many intellectuals of the time, Huang Gongwang found his path to a good career severely limited. He held a minor post as a legal clerk for several years. However, he was charged with tax violation and briefly imprisoned. Completely disillusioned, he then retreated into Taoism. His several nicknames reflected his attitudes: Lonely mountain peak, Abode of Purity, or Silly Taoist Priest.

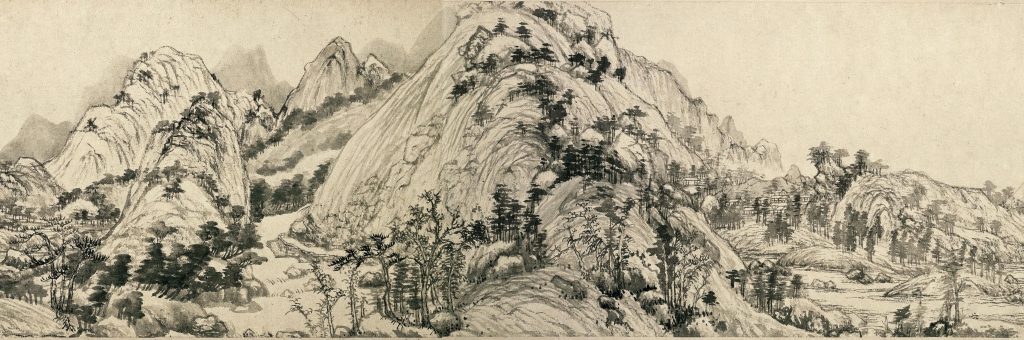

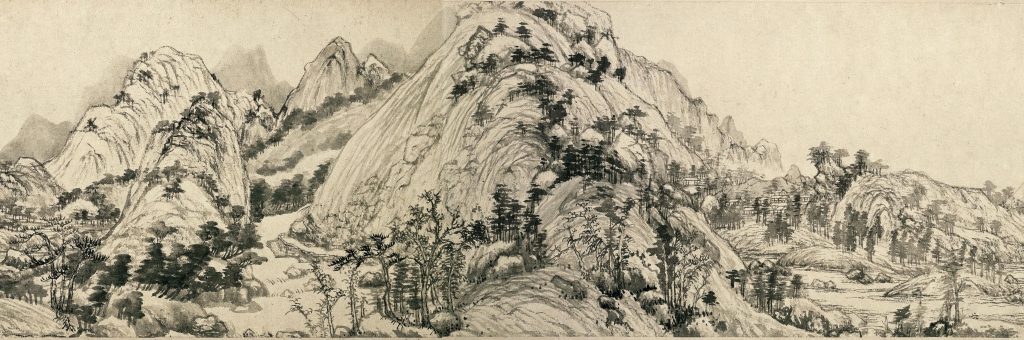

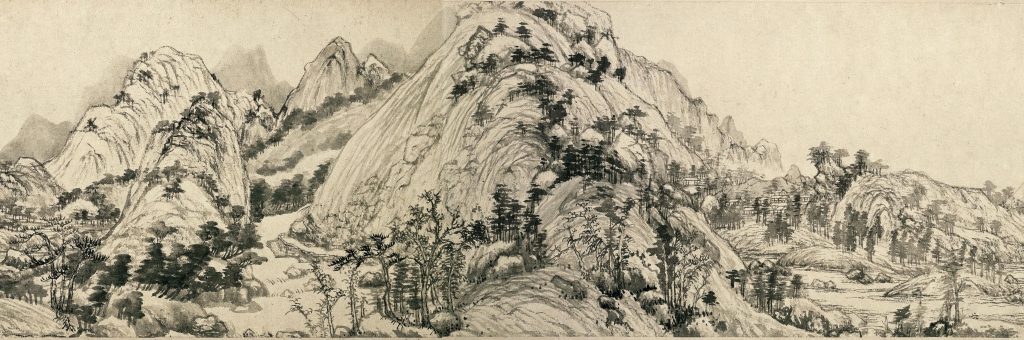

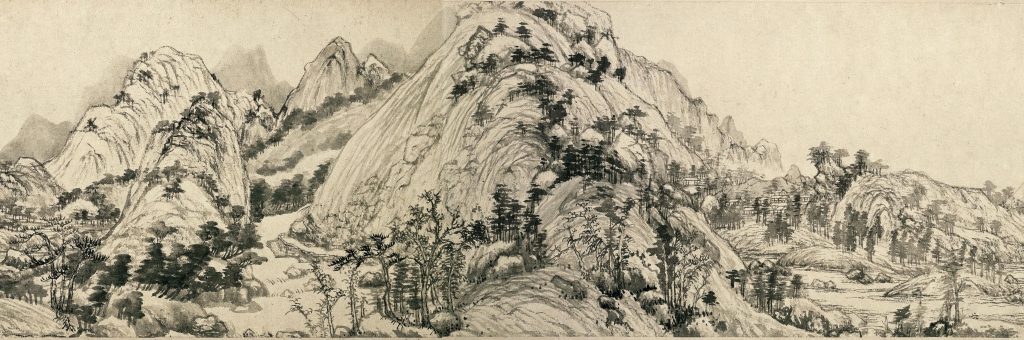

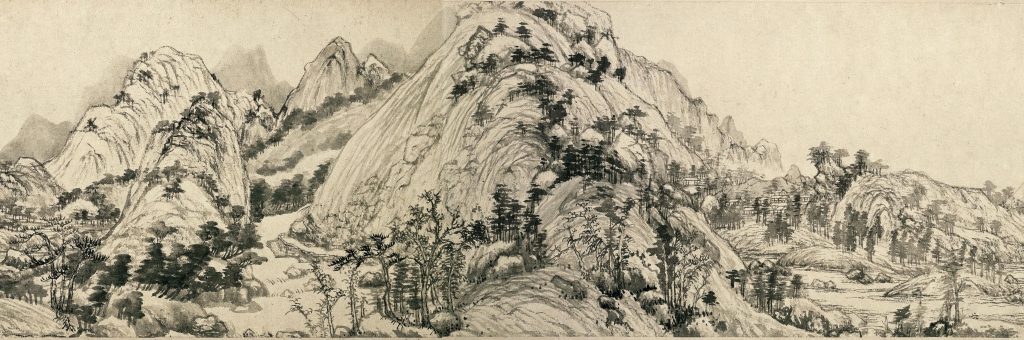

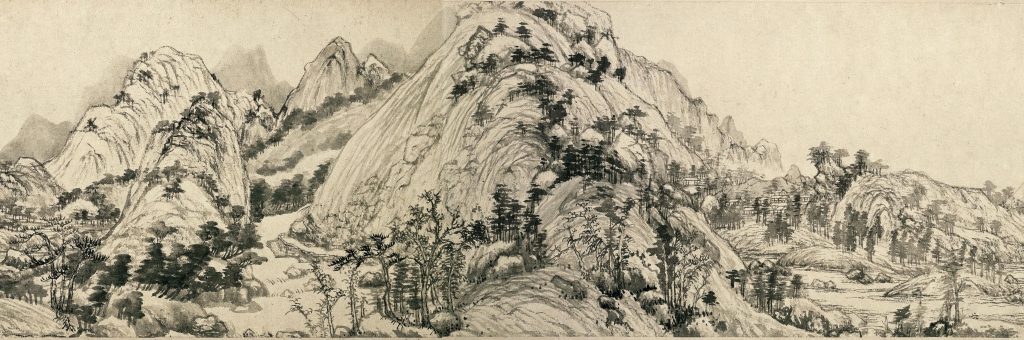

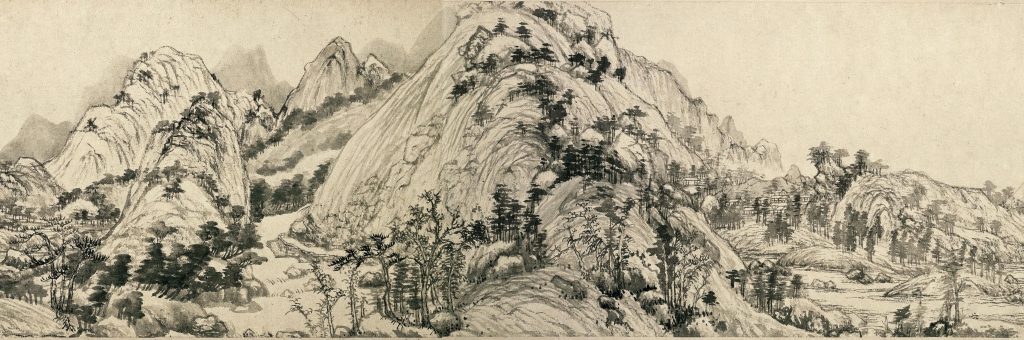

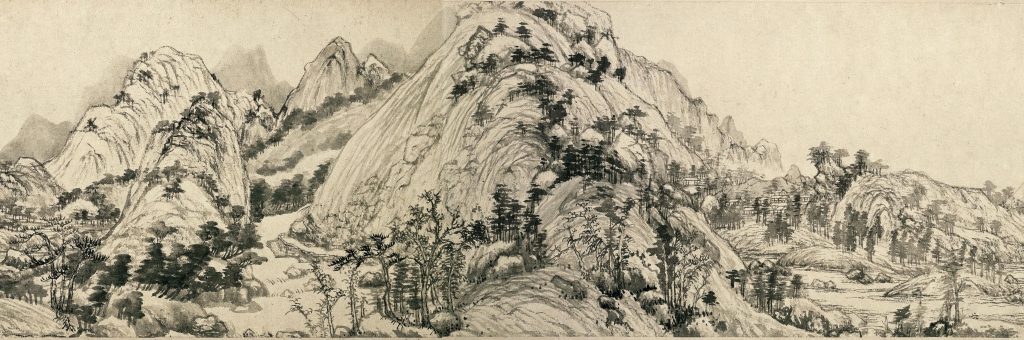

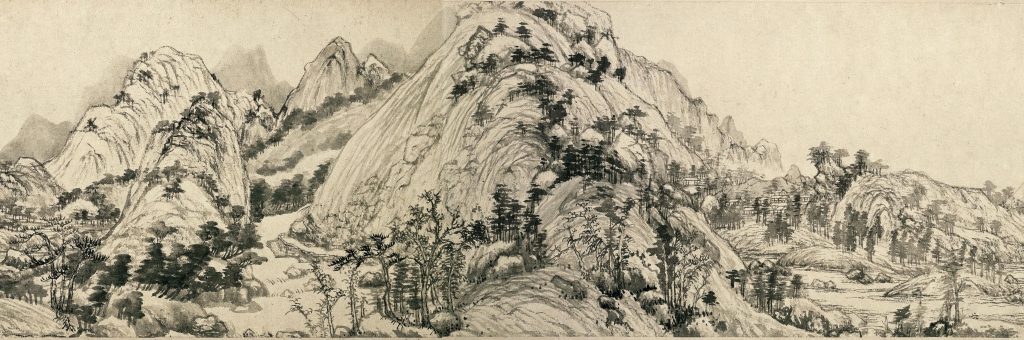

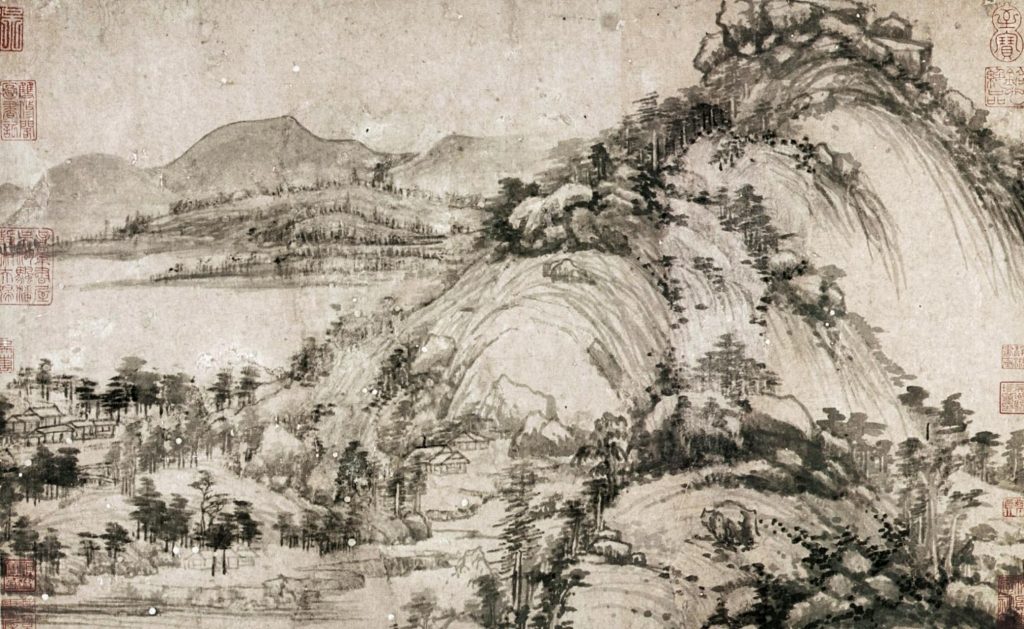

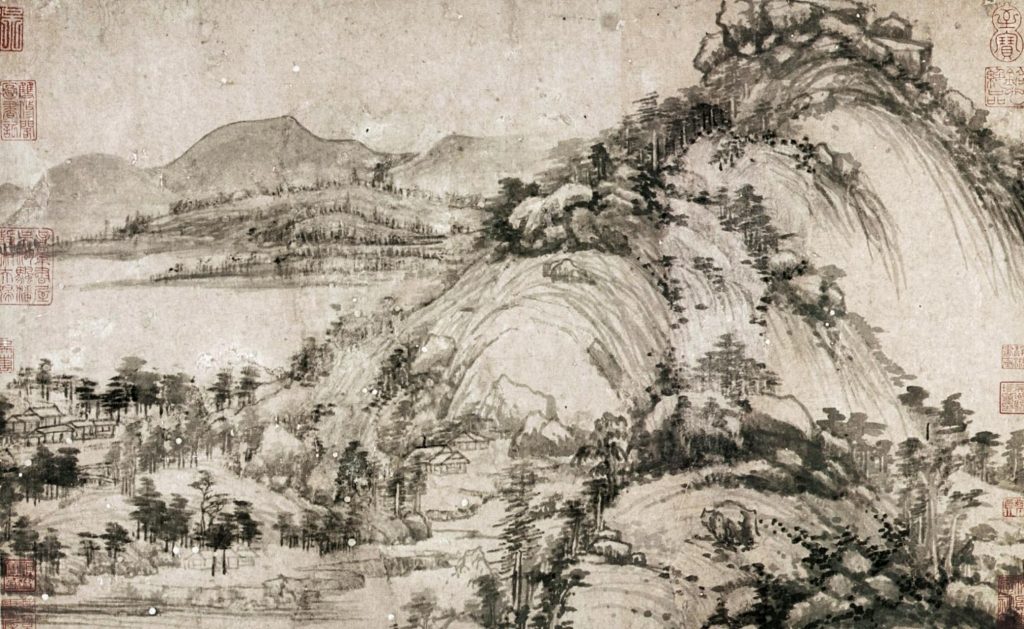

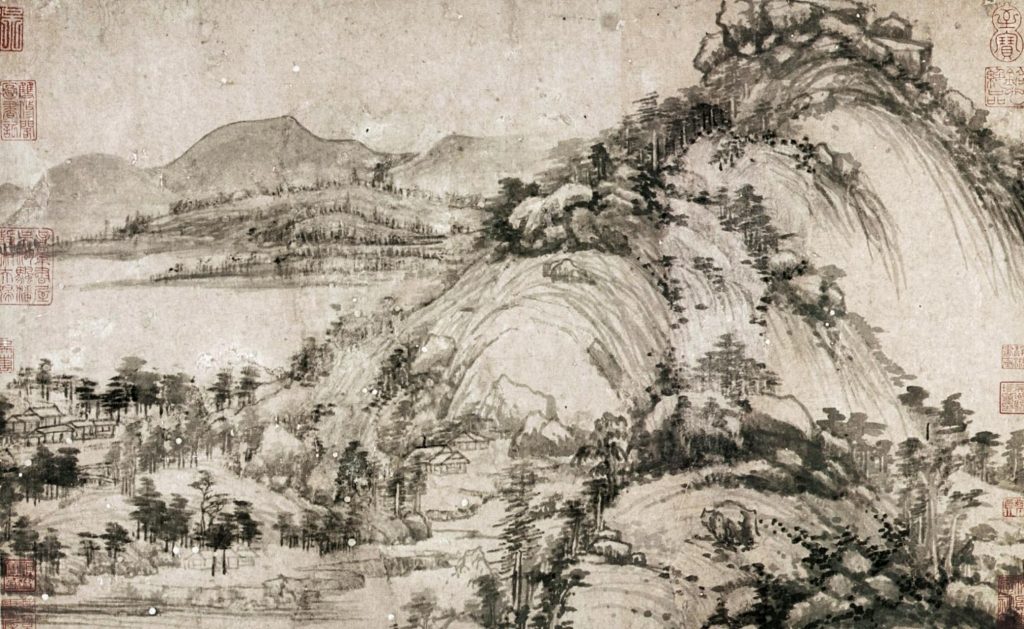

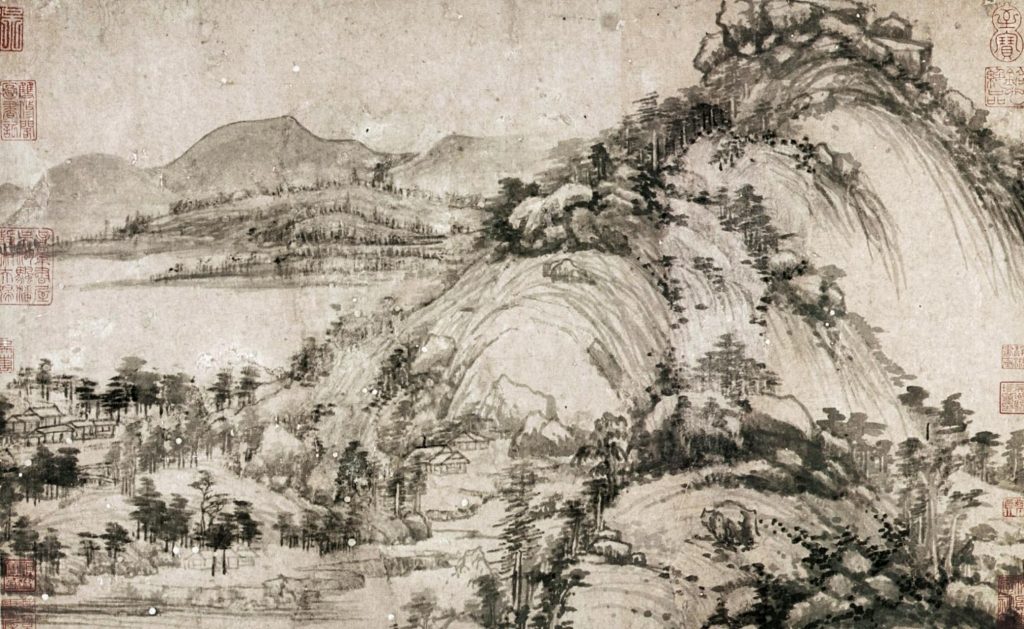

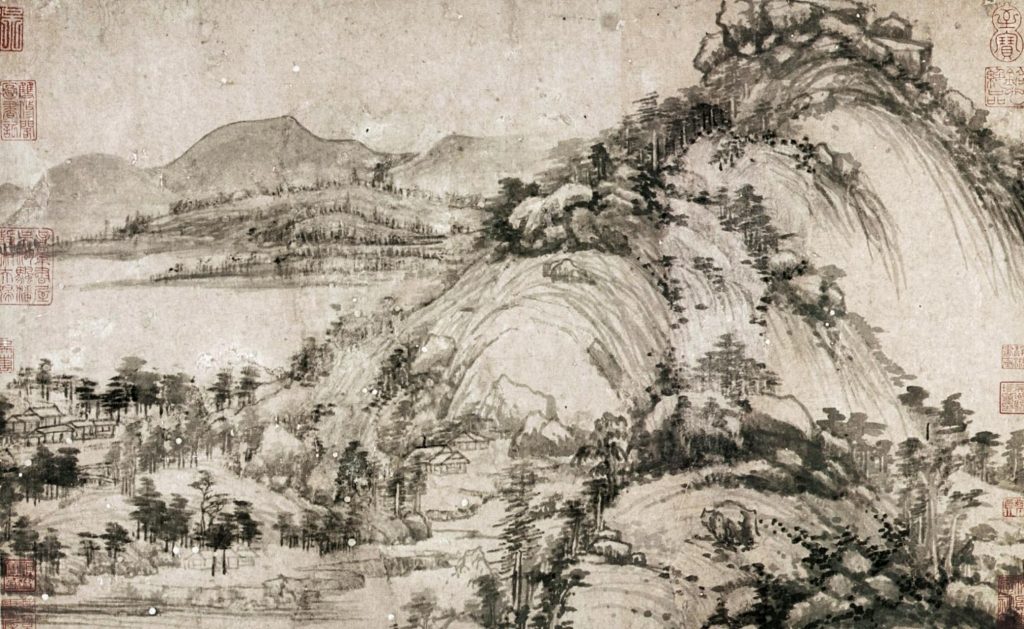

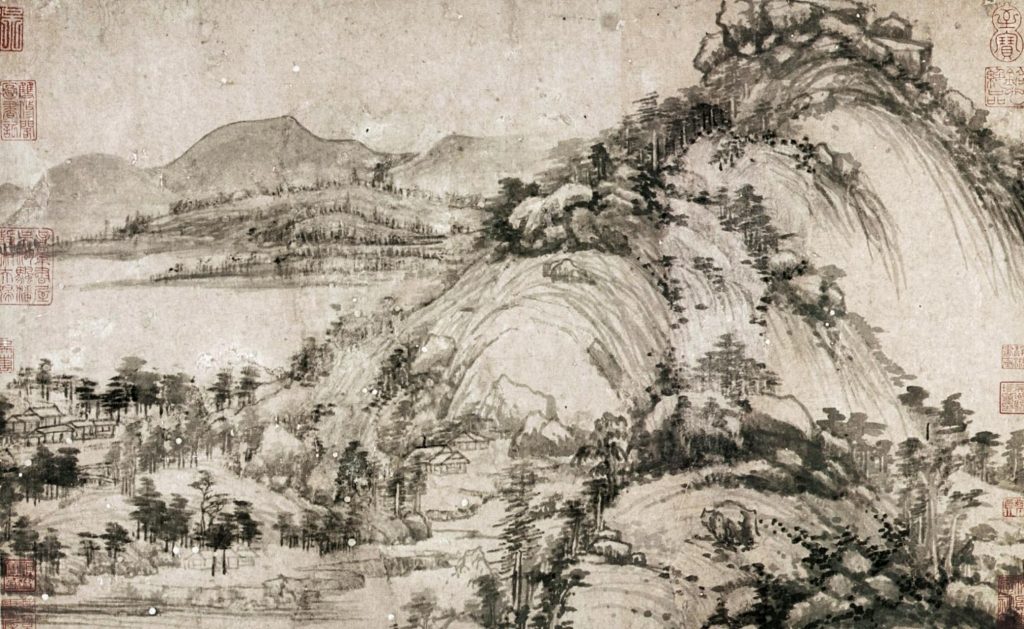

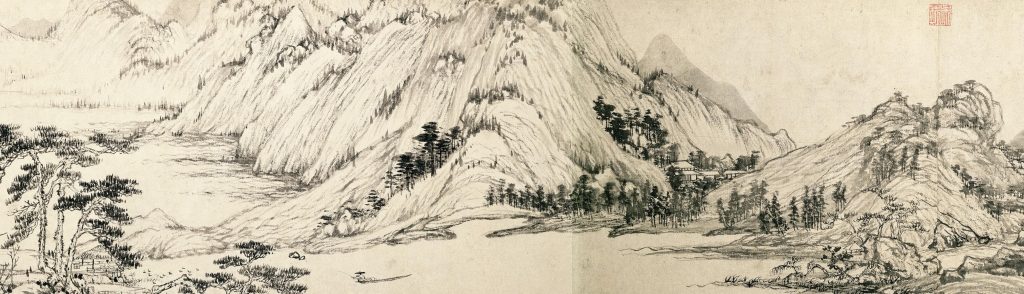

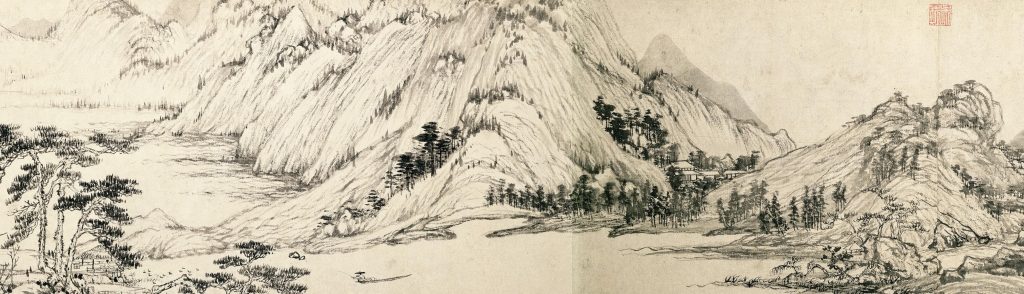

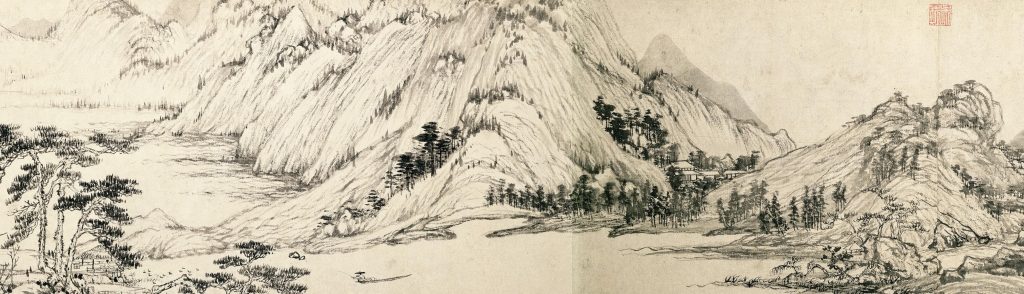

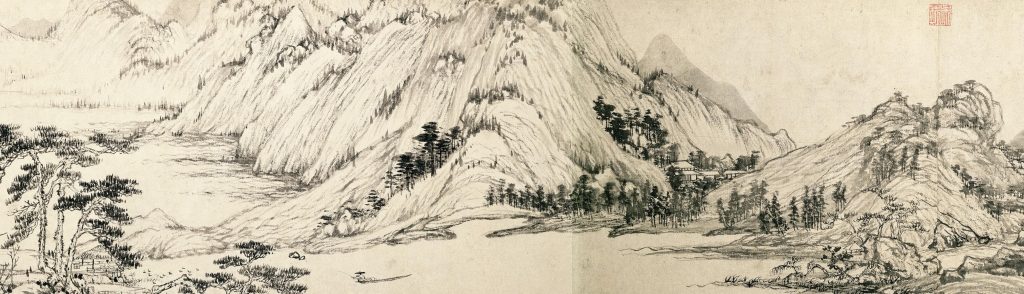

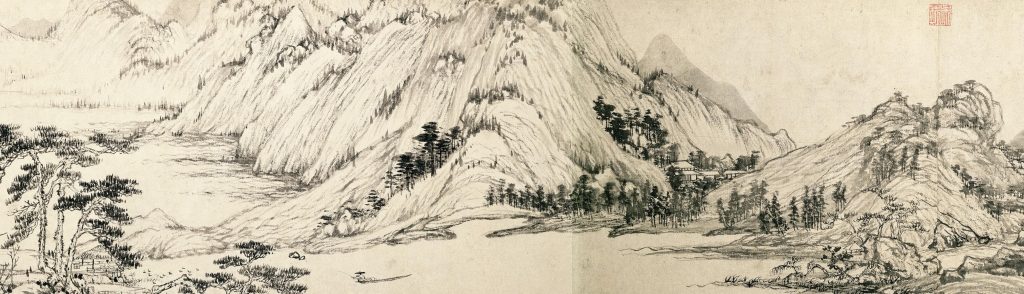

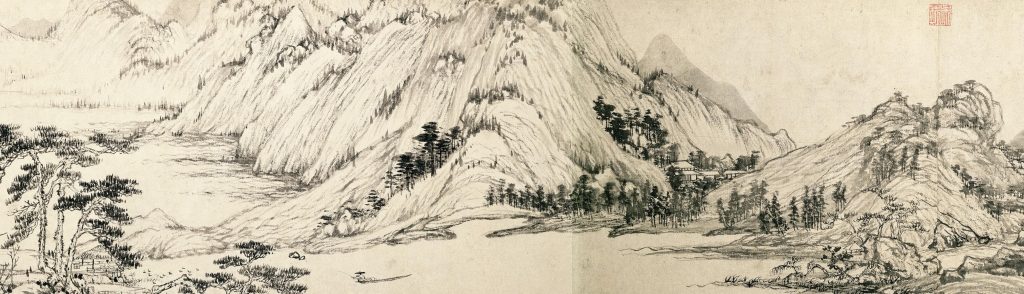

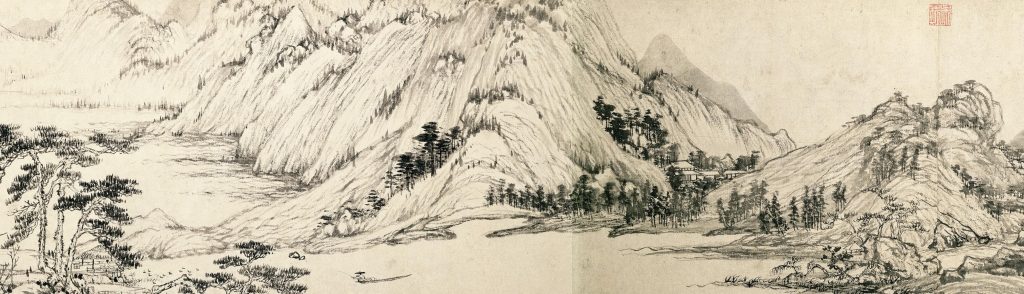

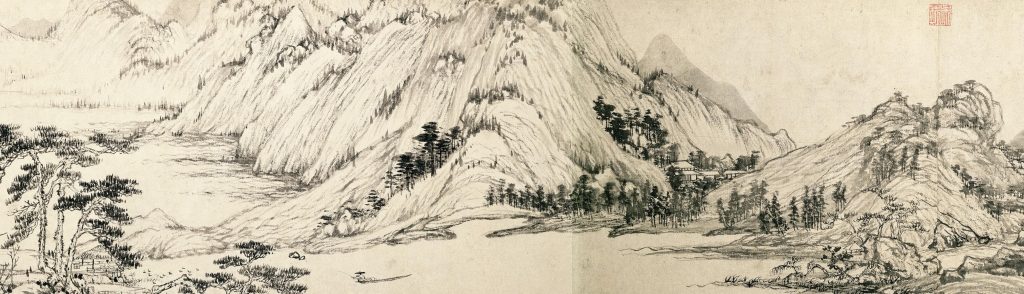

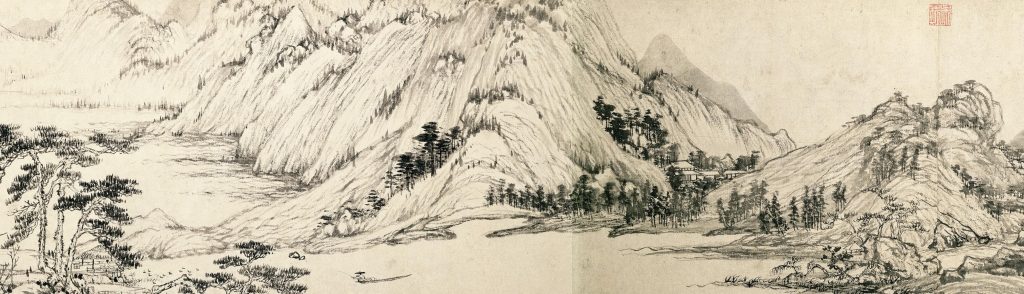

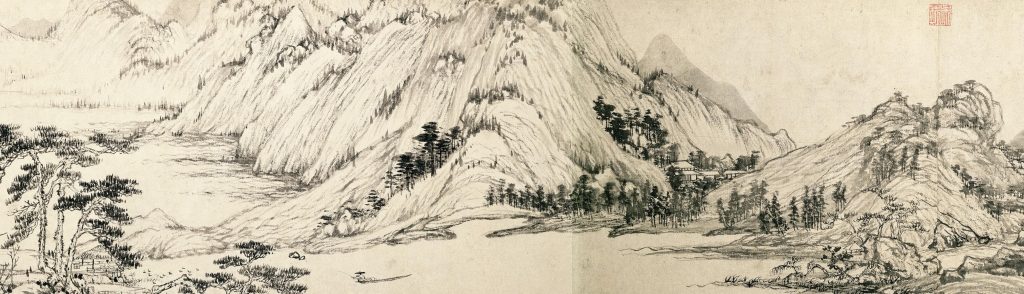

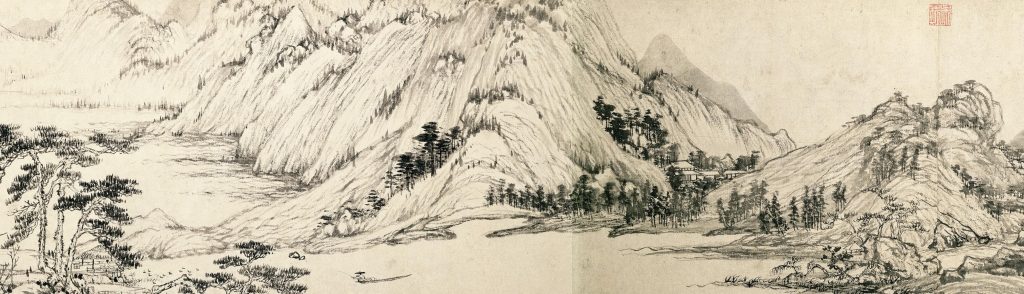

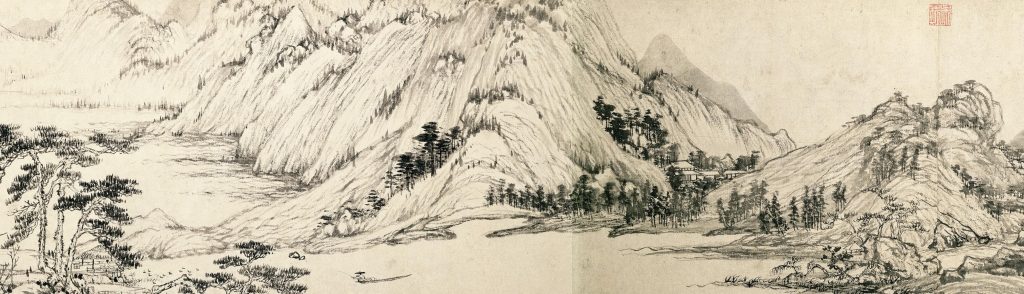

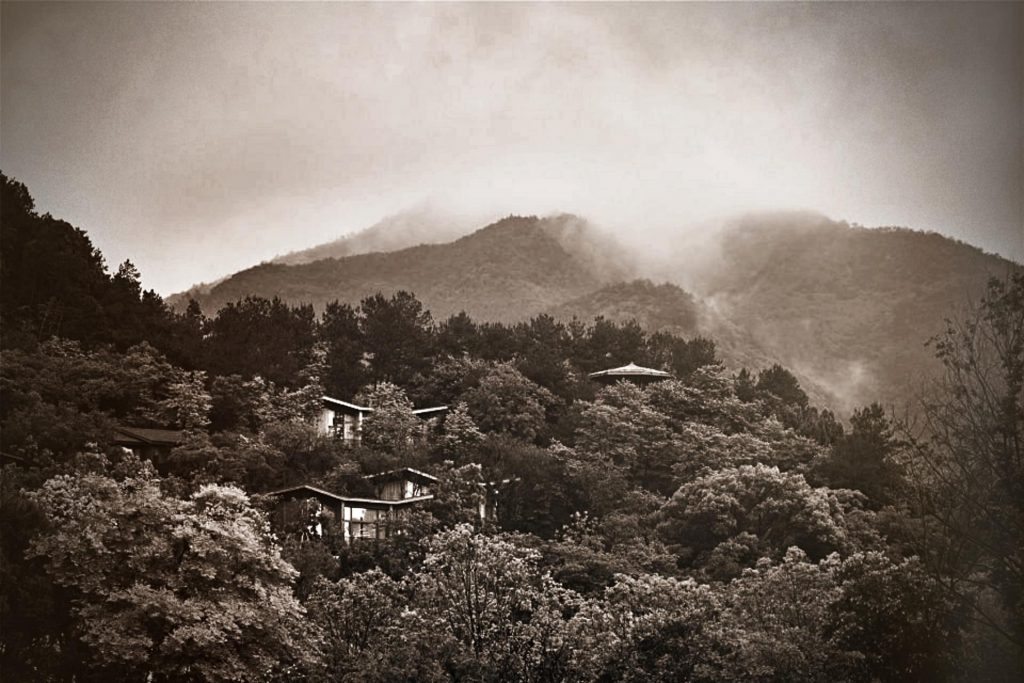

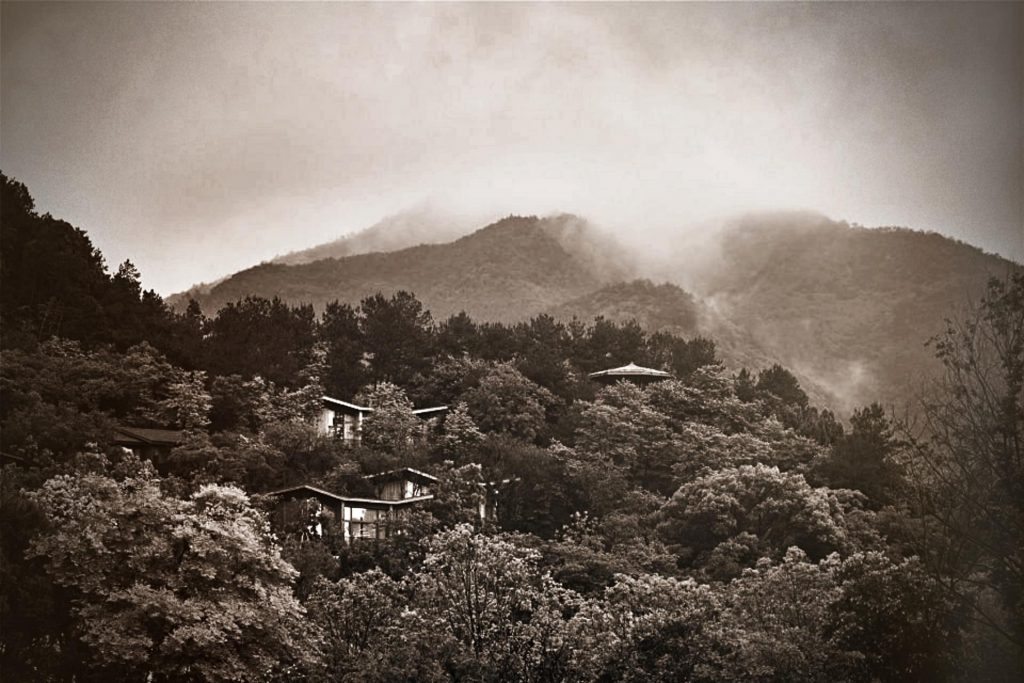

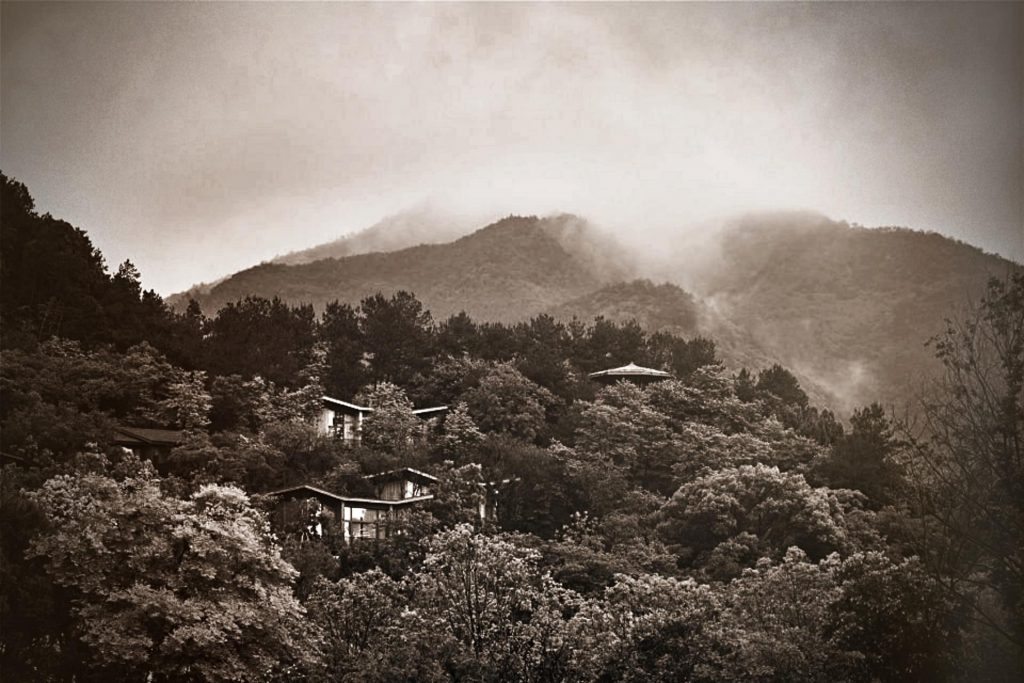

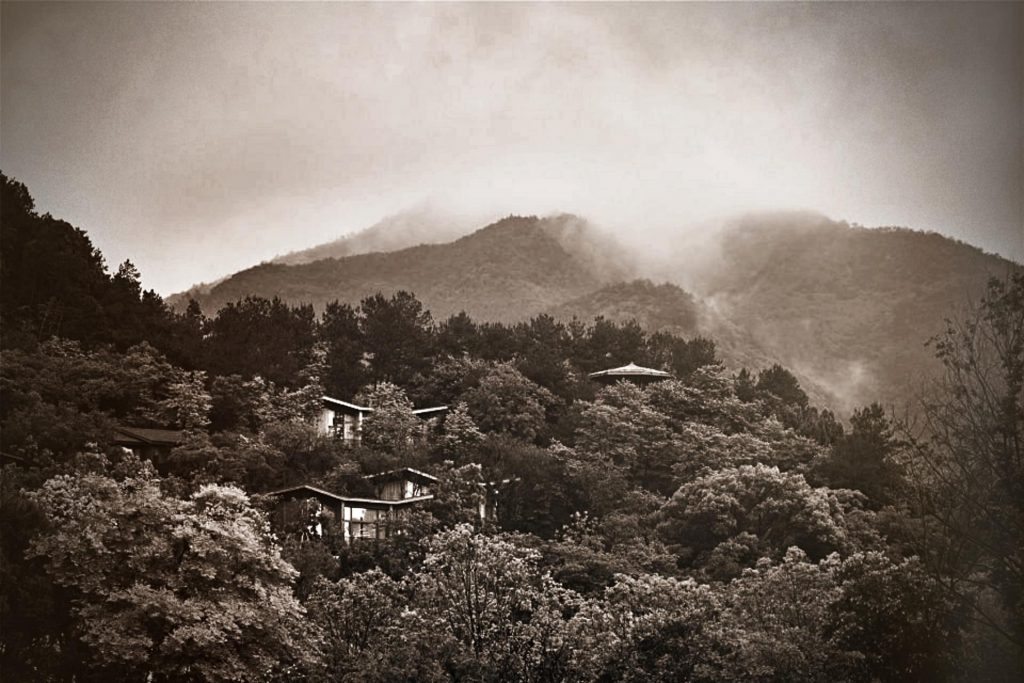

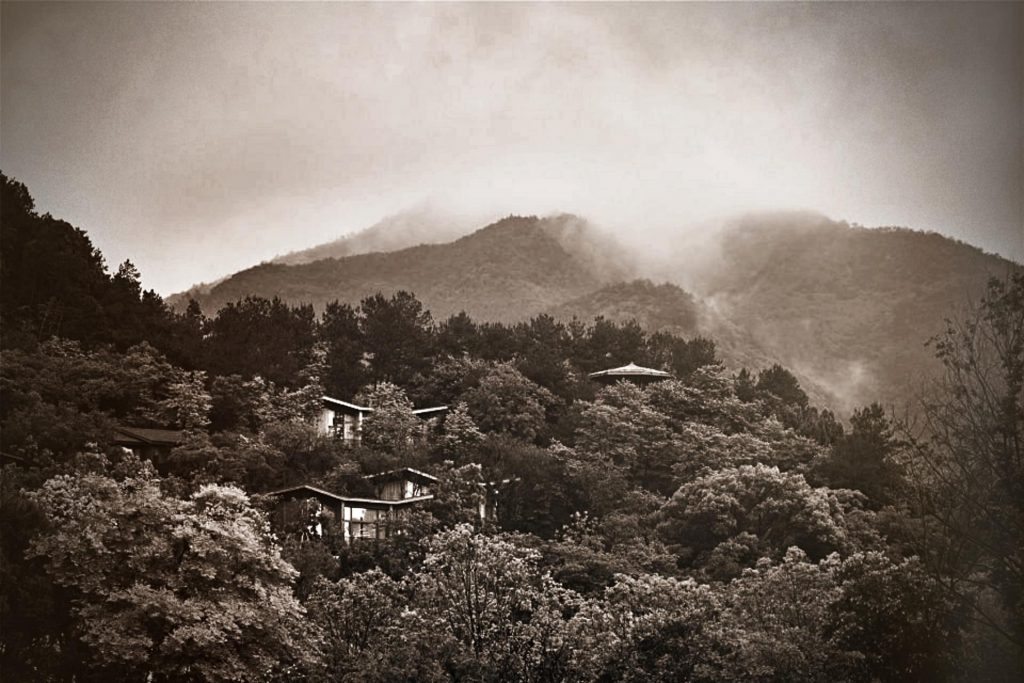

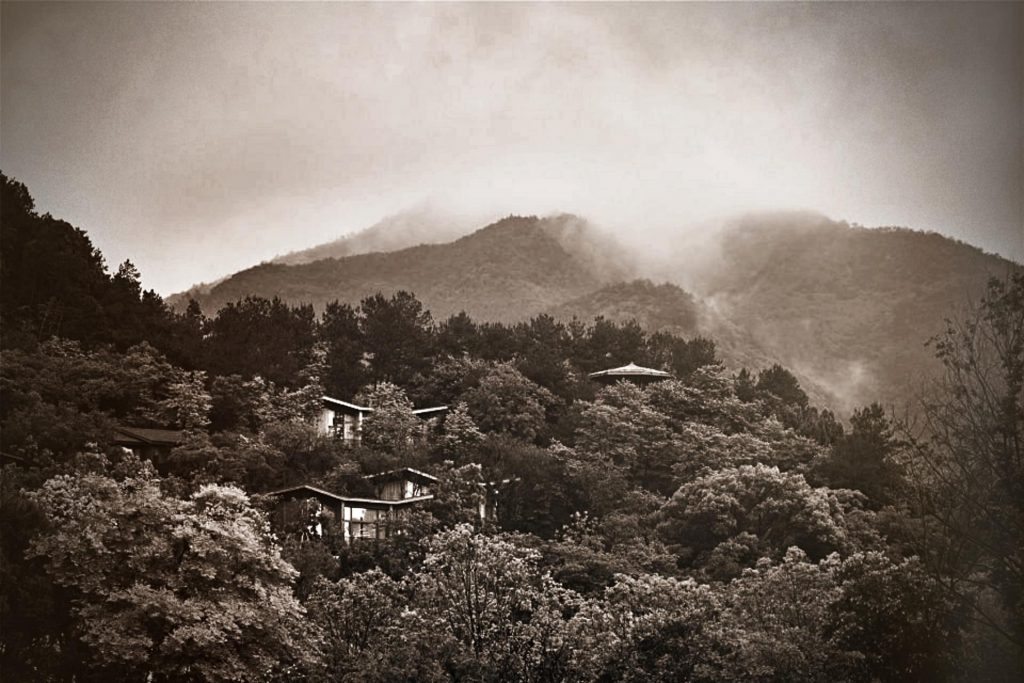

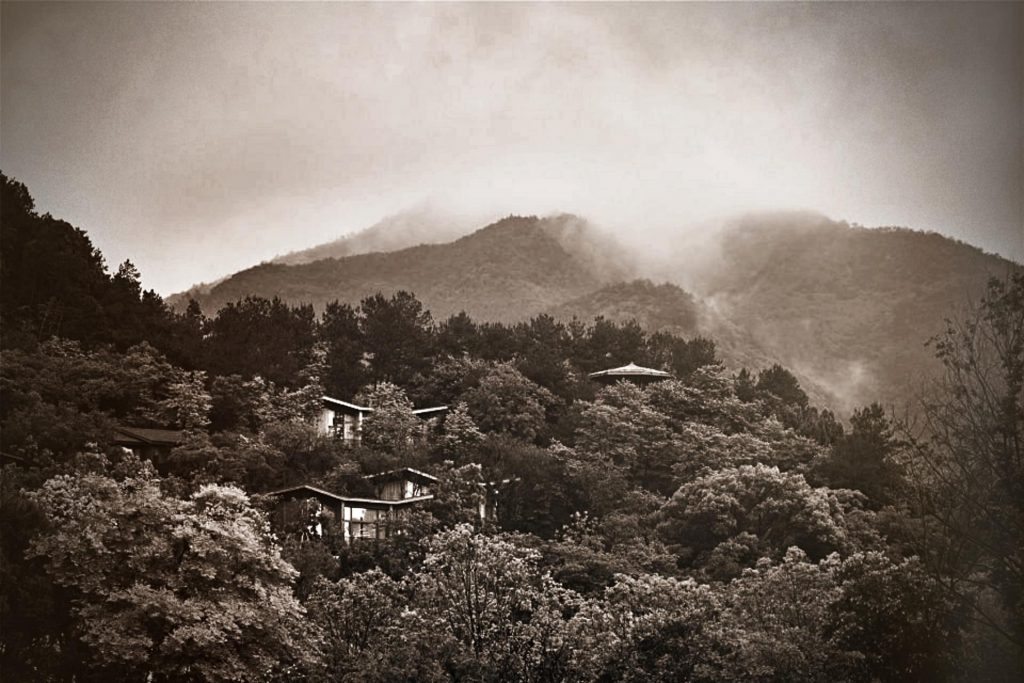

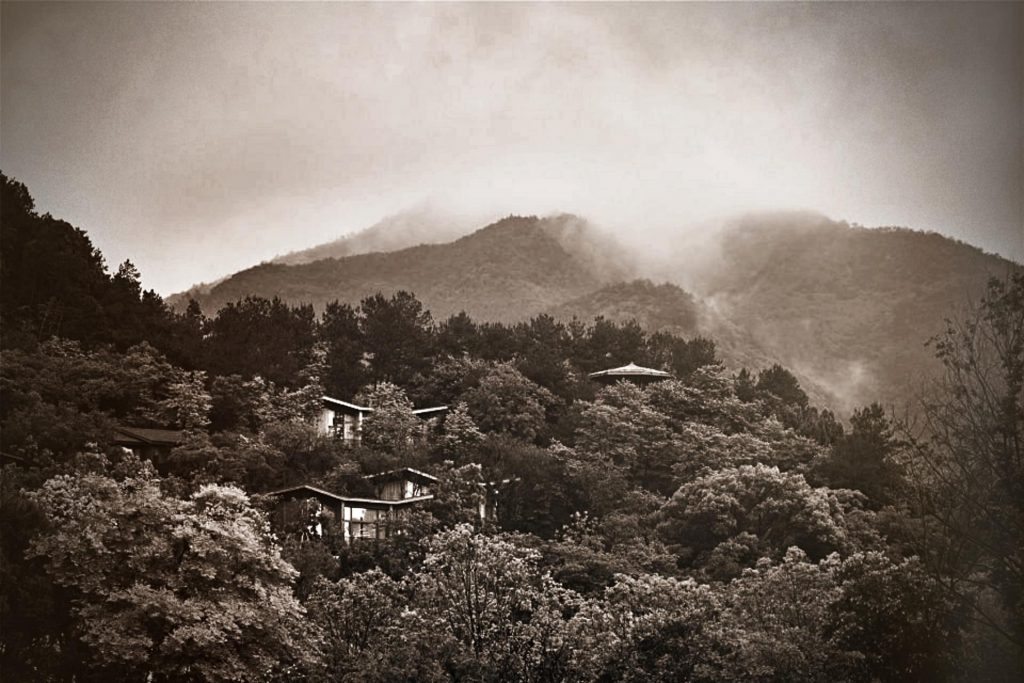

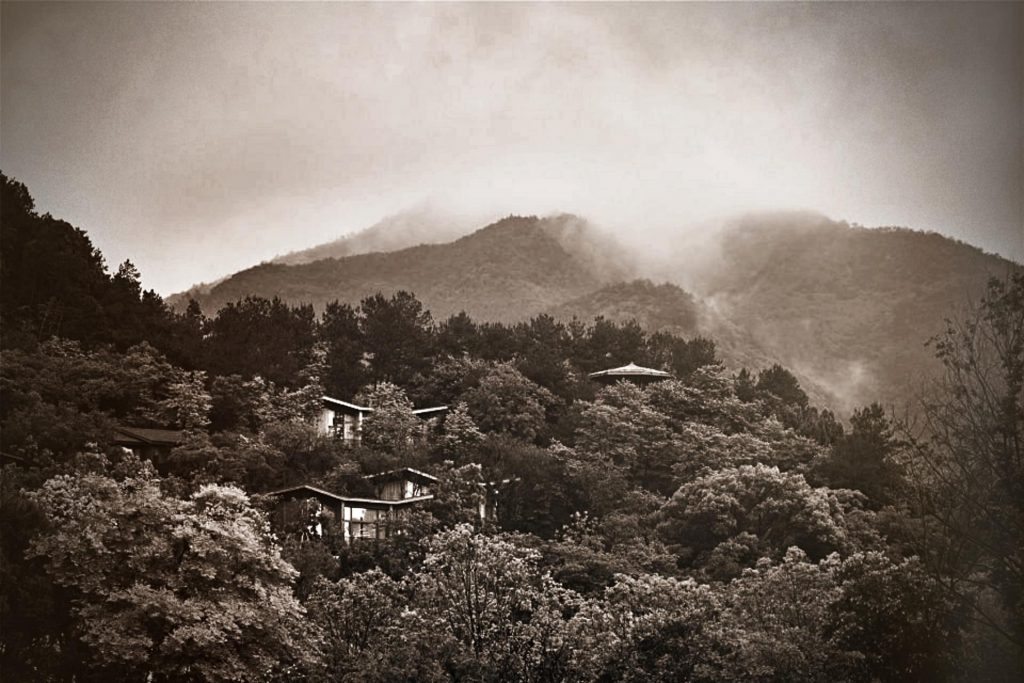

He spent his last years in the Fuchun mountains near Hangzhou, where he taught philosophy to his disciples. Huang Gongwang began serious studies in painting only at the age of 50. Around 1350 he completed one of his most famous works Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains. It is a kind of manifesto of the secluded life.

Initially, there was only one scroll of Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains. In 1650, Wu Hongyu, one of the owners of the painting, liked it so much that he had it burnt shortly before he died. He hoped that in this way he could bring it to the afterlife with him. Luckily, Wu Hongyu’s nephew rescued the artwork from complete destruction. However, the painting was already aflame and torn into two. The smaller piece became known as The Remaining Mountain. It is now in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou. The longer piece, The Master Wuyong Scroll, ended up in the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

The scroll depicts early autumn on the Fuchun River. The image sweeps across the horizon, revealing a majestic, spacious landscape. Mountain peaks rise to the sky, while deep gorges stretch between. The pines stand proudly and the distant forest is hidden in a haze. The trees are uneven, dense, or rare. Country houses, bridges, boats, and human figures are lost in the landscape. The tops of trees on the mountains are vaguely visible, giving a sense of rhythm and tranquility to the painting.

Sketching out the entire composition in one sitting, the artist carried the scroll with him when he traveled. He went over it when his mood was right, without quite finishing it. Huang Gongwang used very dry brush strokes together with light ink washes to build up his paintings. It allowed him to build dynamically complex masses. His loose drawing gives the scenery a slightly unkempt look. However, it also diverts our attention from the calculated construction of the scroll. Subsequent imitators lost this effect of spontaneity in their more schematic approach to painting.

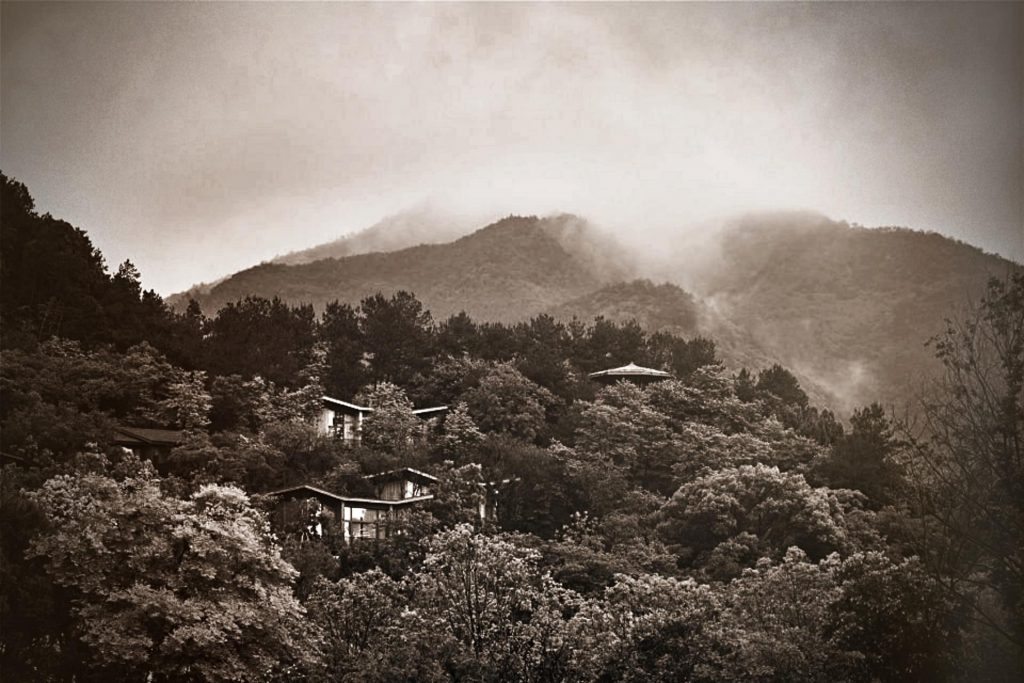

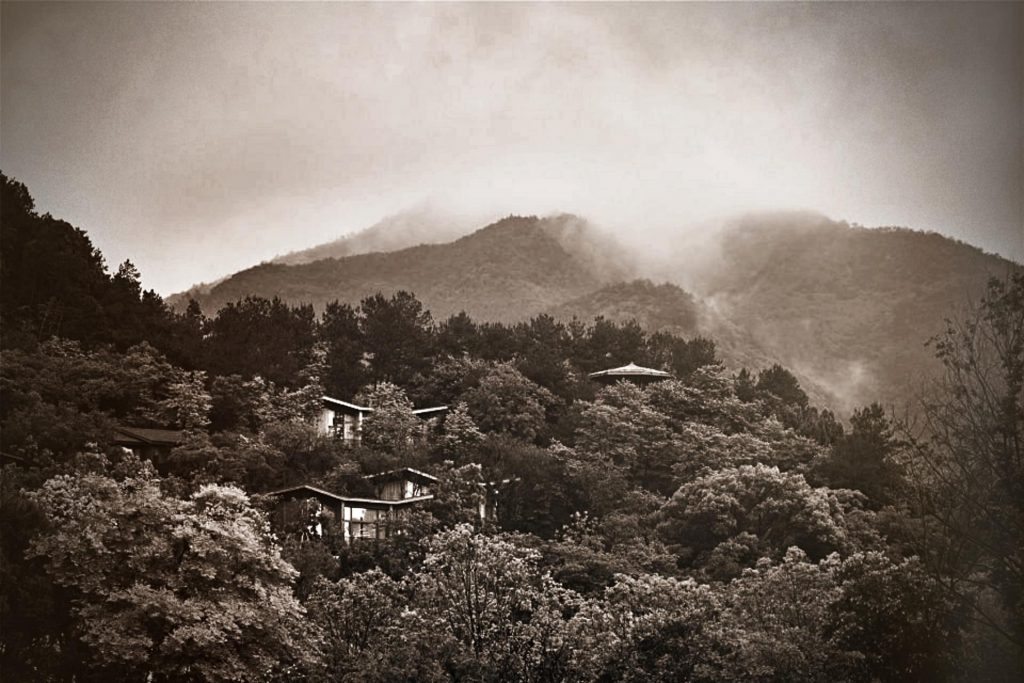

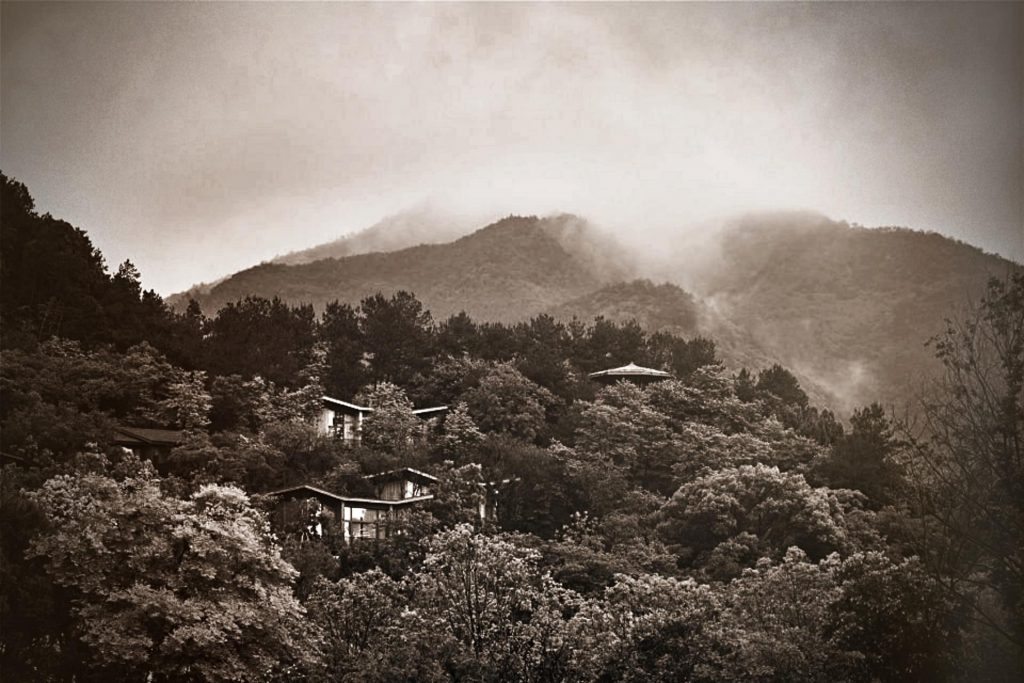

There is harmony between man and nature in the painting. It reveals Huang Gongwang’s cultivation of himself with painting in his old age. He showed us the beauty of Southern China with its scattered hills and flowing rivers. Now in this area is the Fuchun Resort with guest houses combining Chinese cultural elements with Western design.

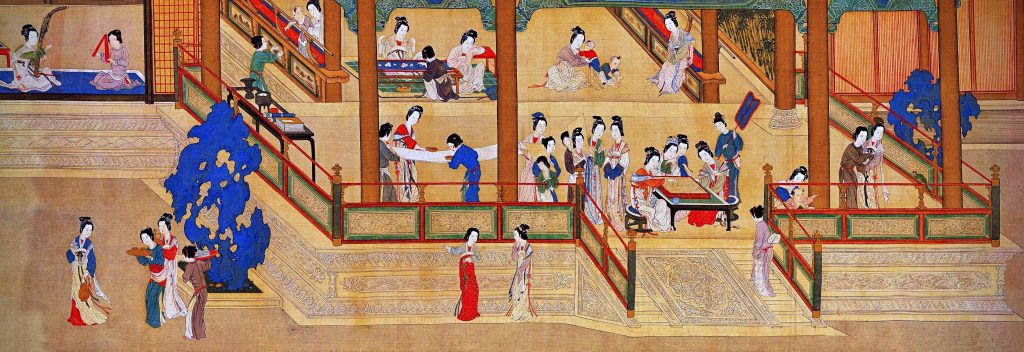

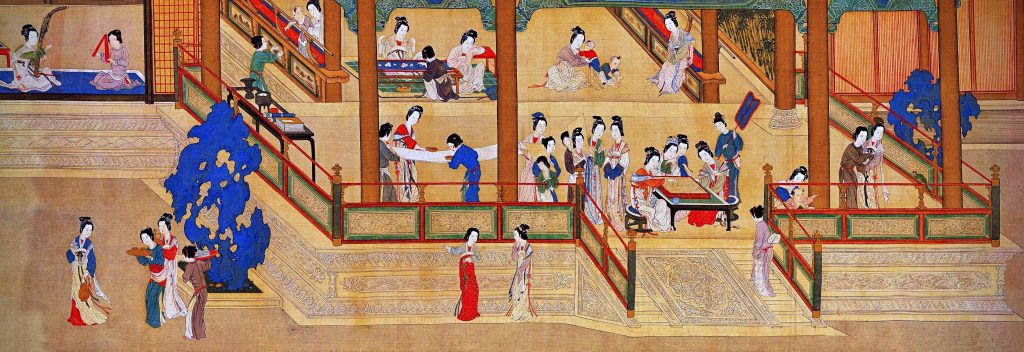

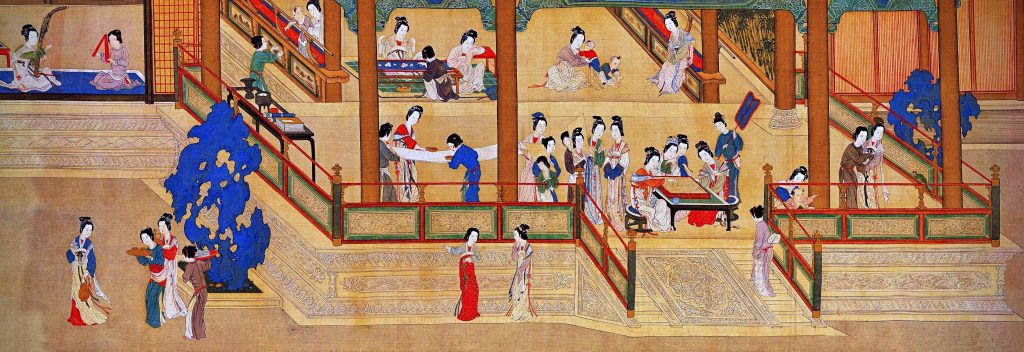

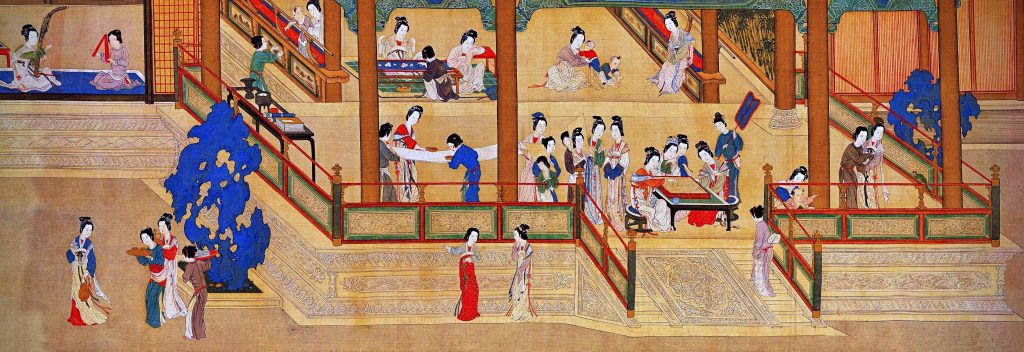

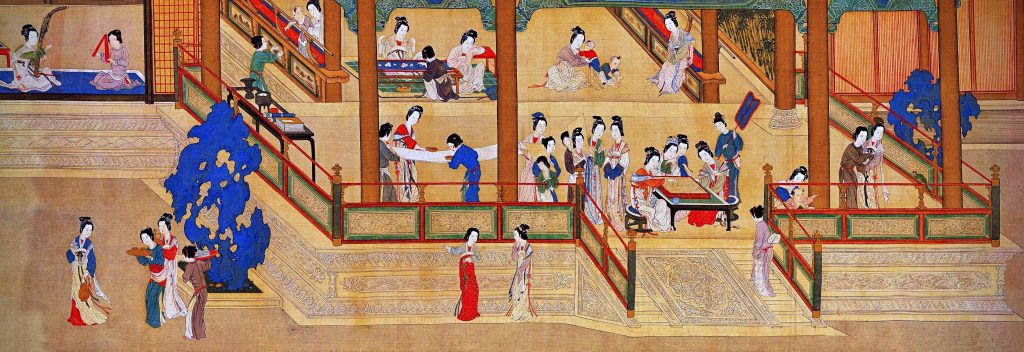

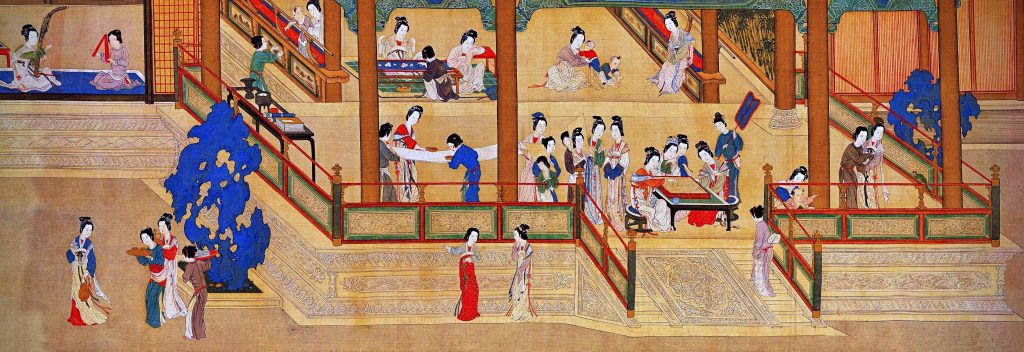

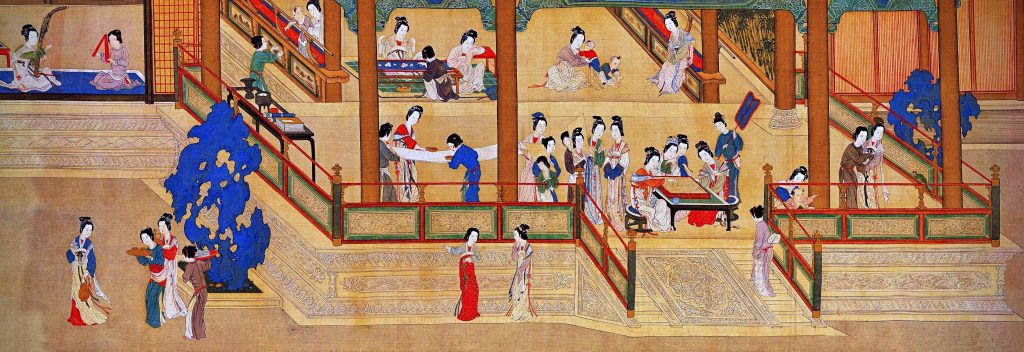

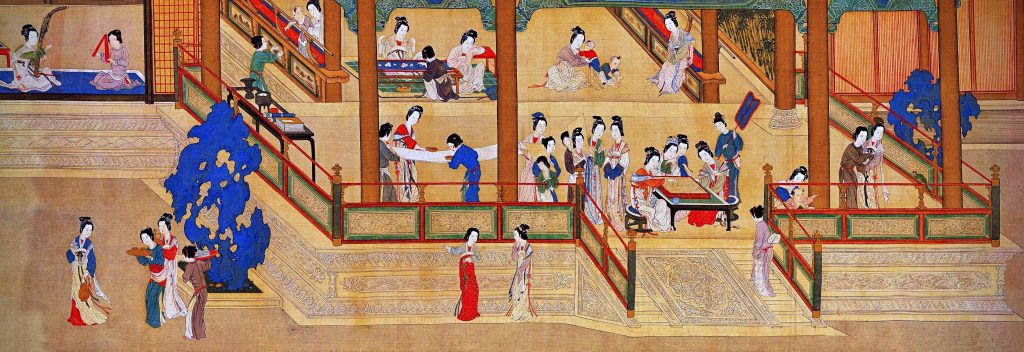

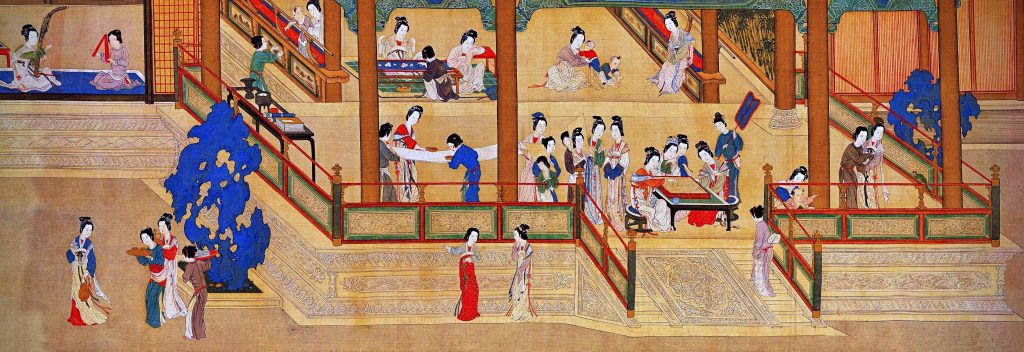

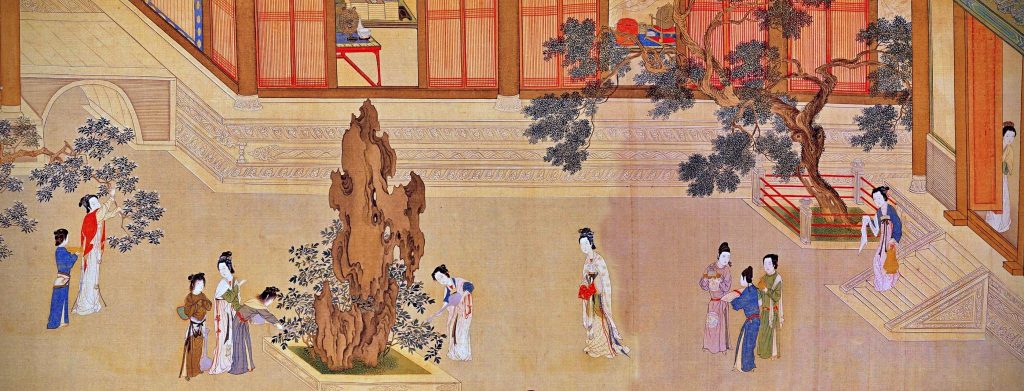

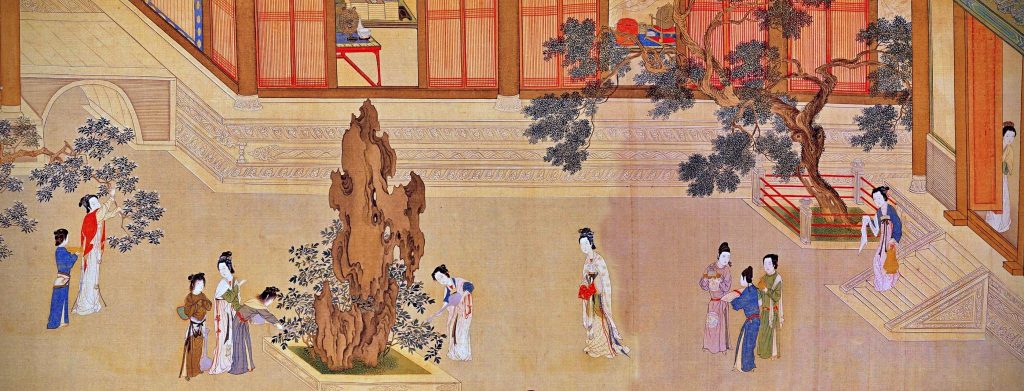

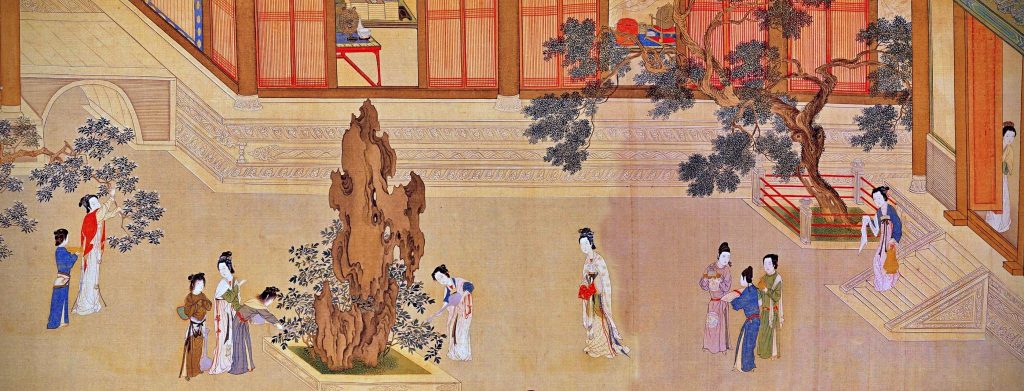

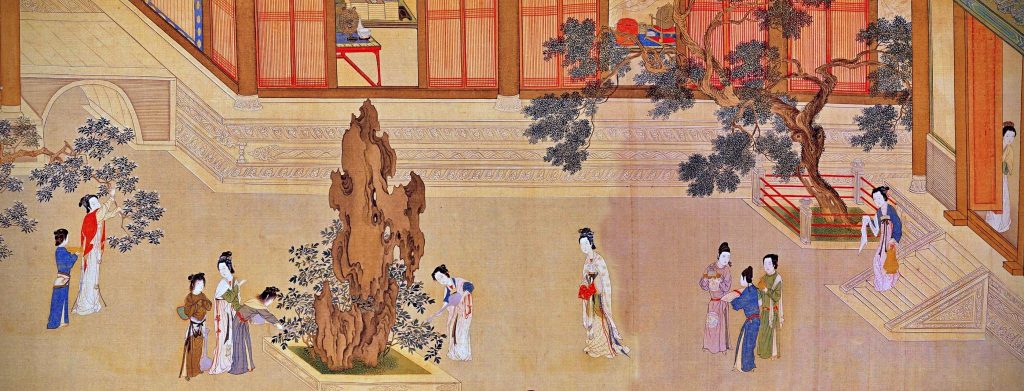

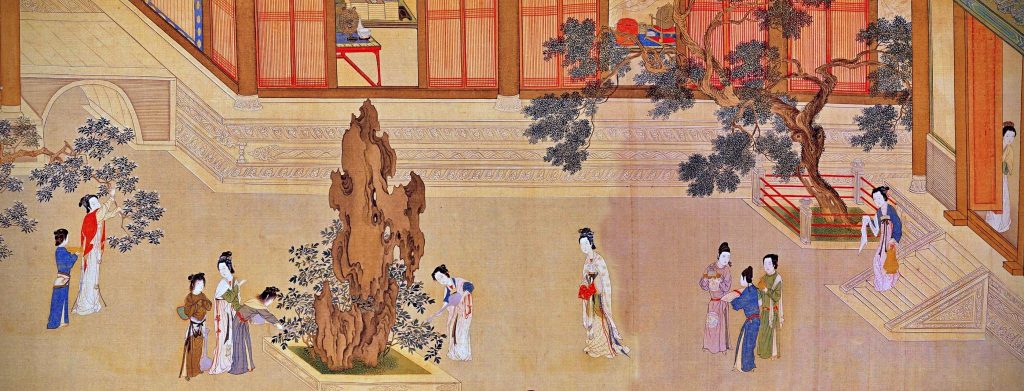

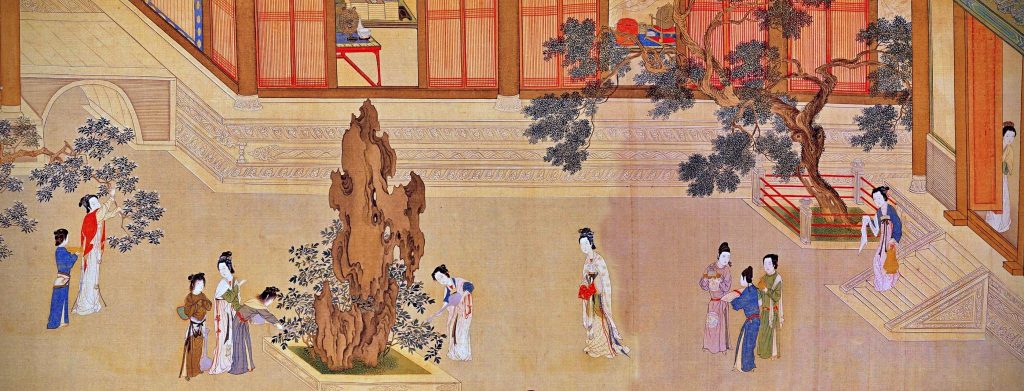

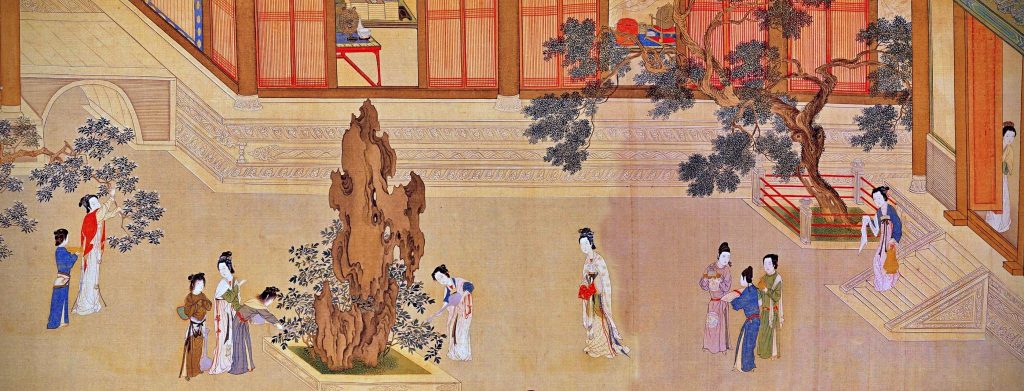

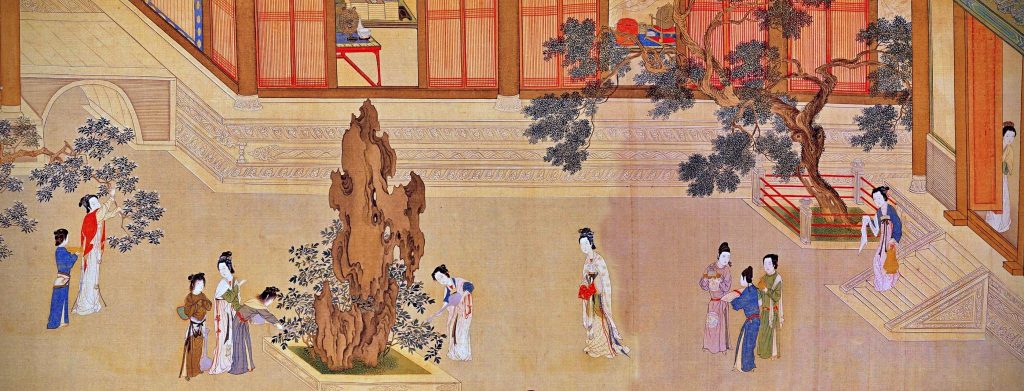

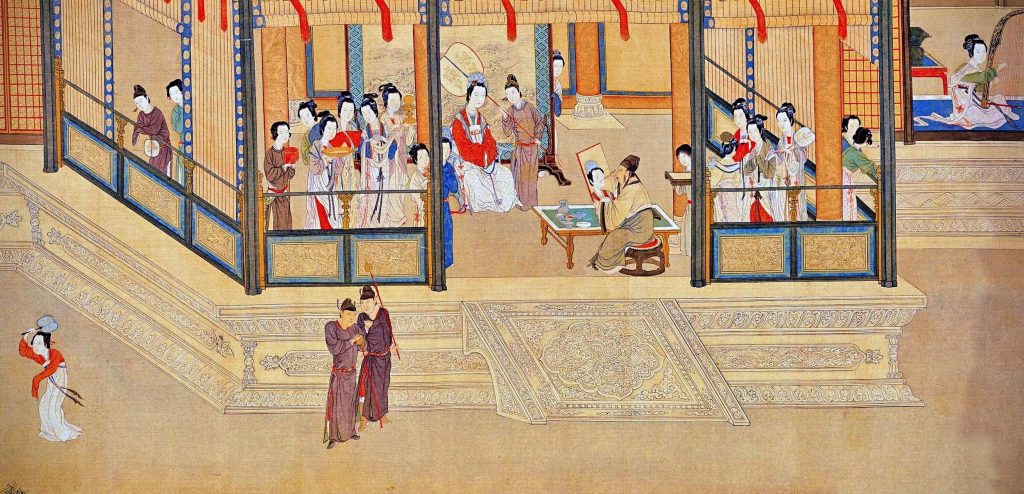

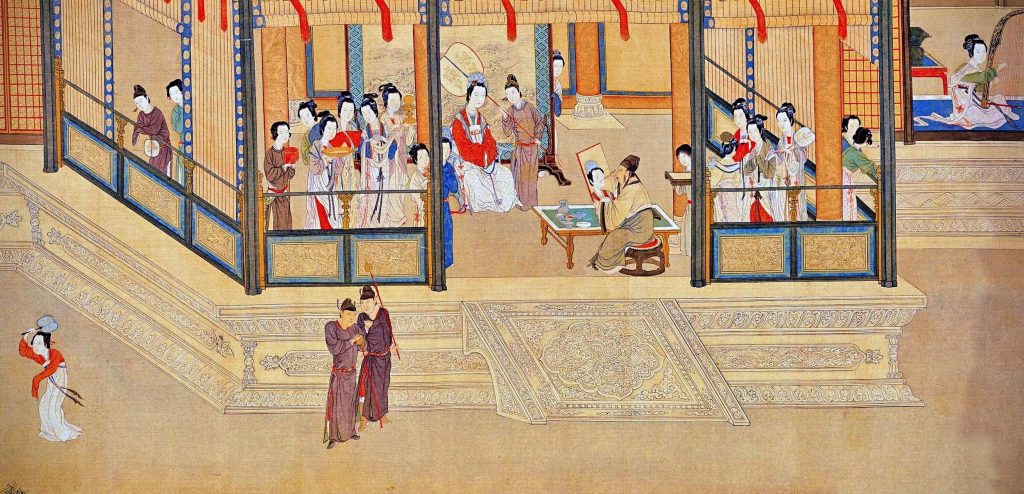

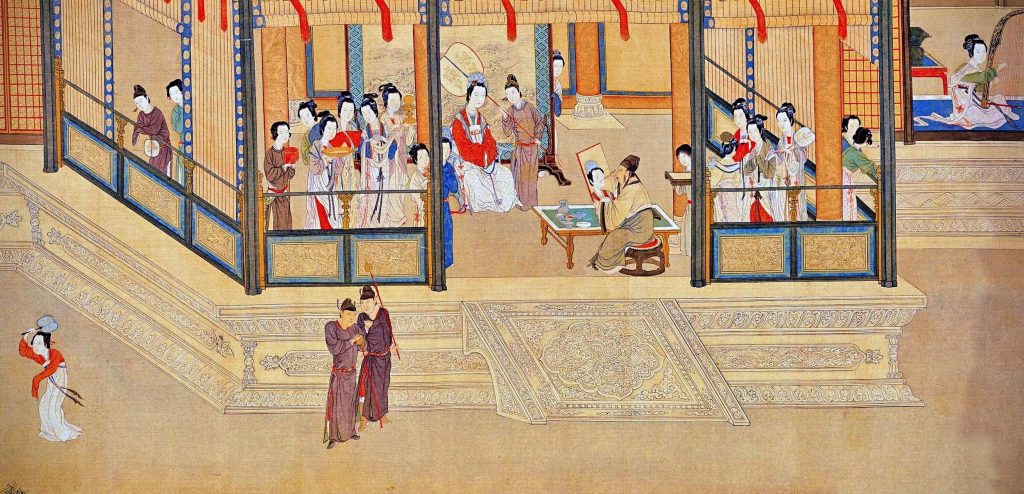

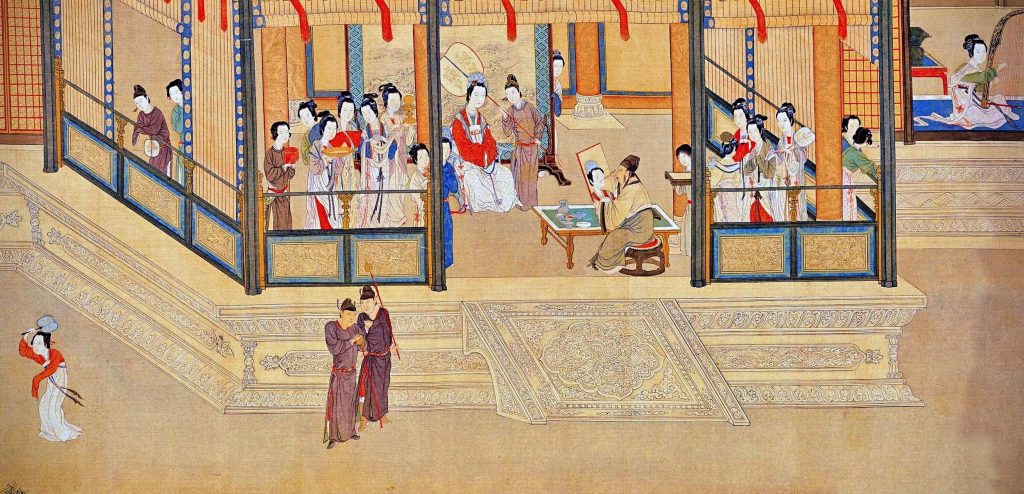

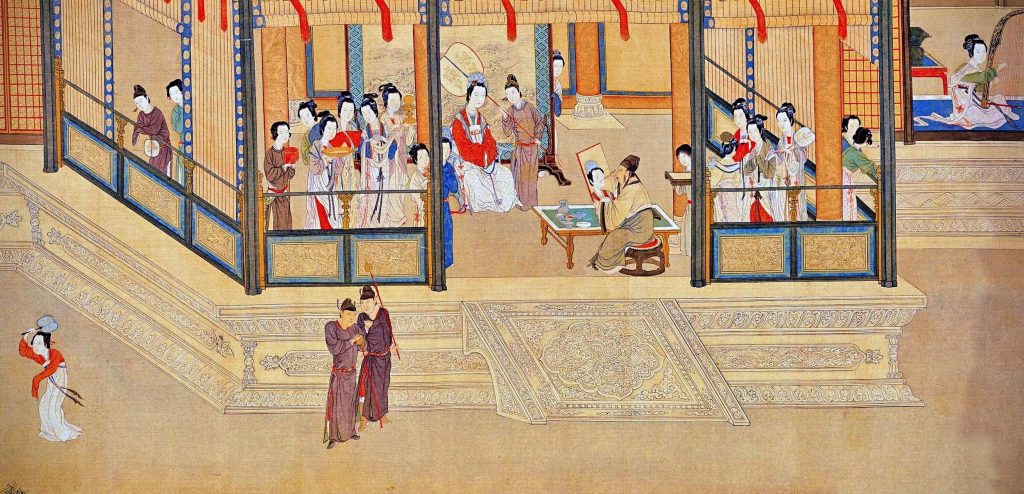

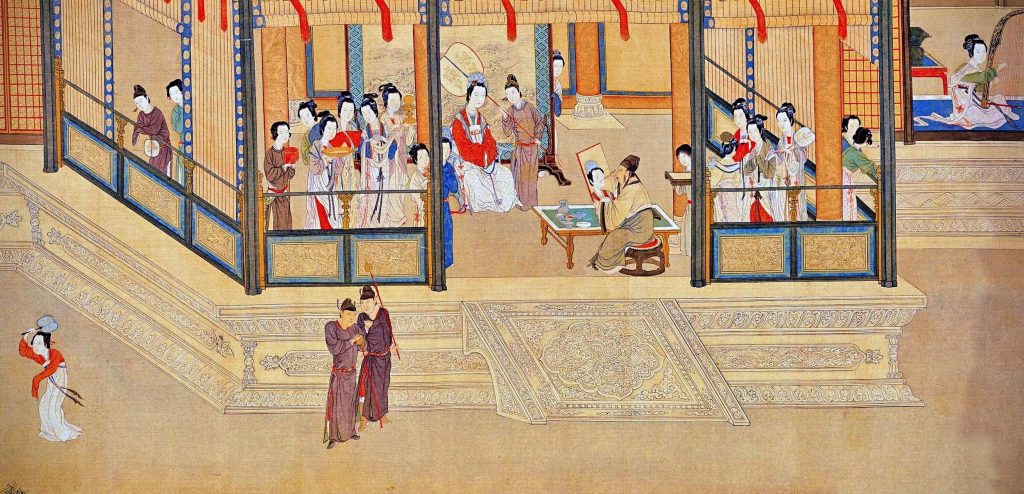

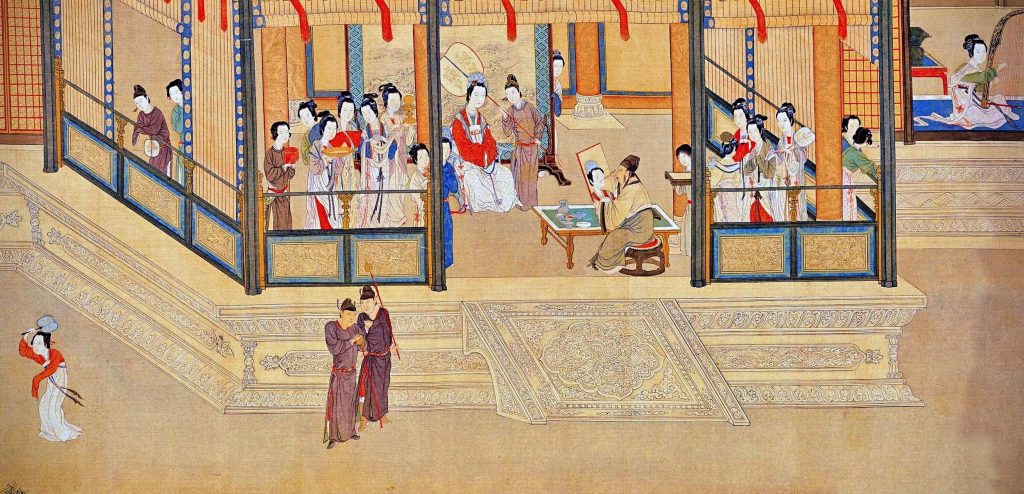

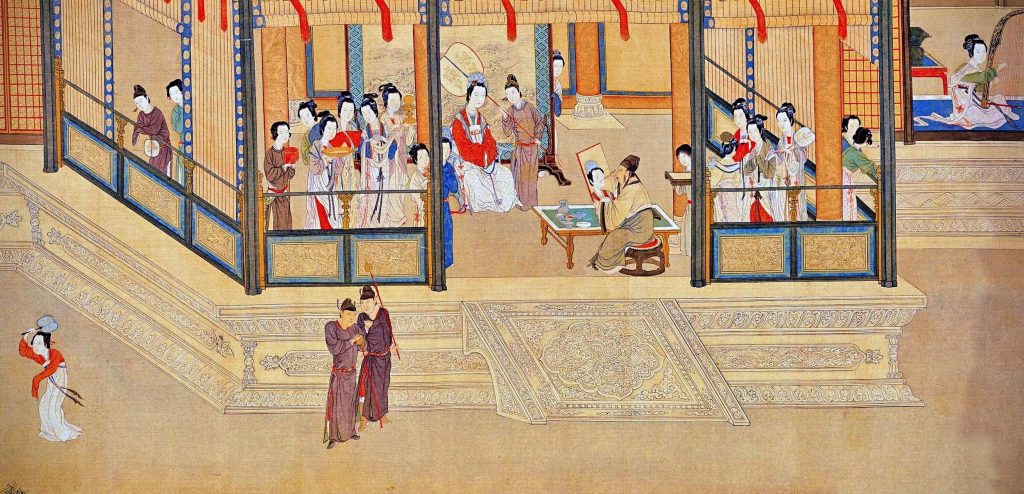

Qiu Ying (ca. 1494 – ca. 1552) (pronounced Ch’iu Ying) was born to a peasant family in Taicang. After moving to Suzhou, he became an apprentice to a lacquer artisan. Despite his family’s humble origins, he had a talent for painting. He worked in the gongbi style, a careful realist technique in Chinese painting. It uses brushstrokes that outline details very precisely. It is often highly colored and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects.

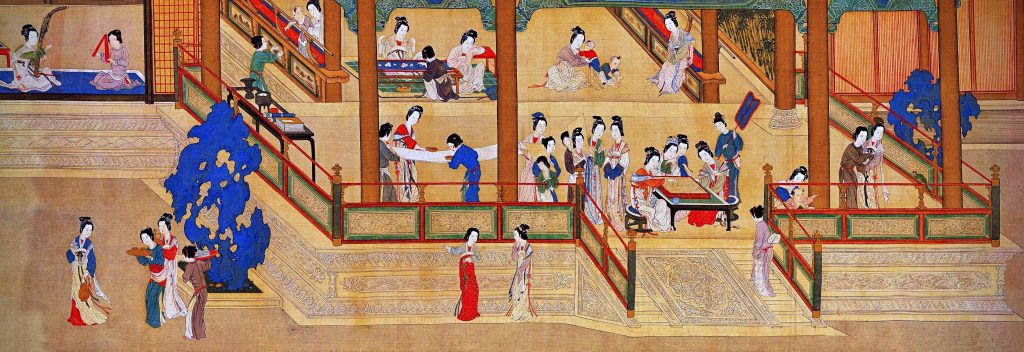

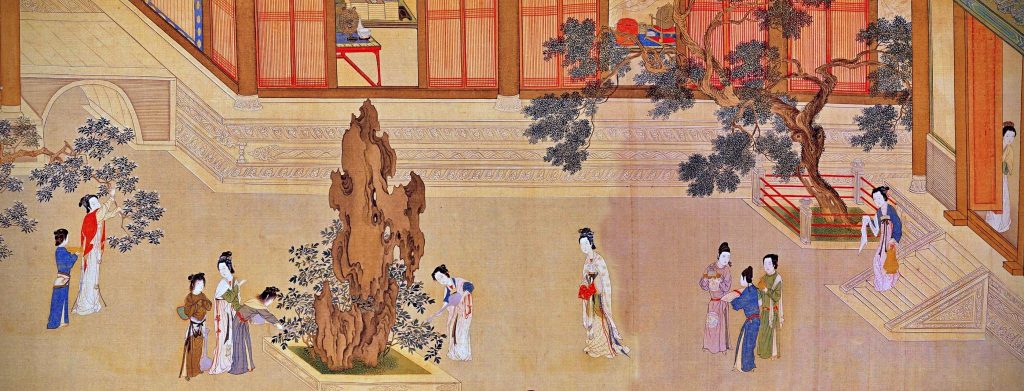

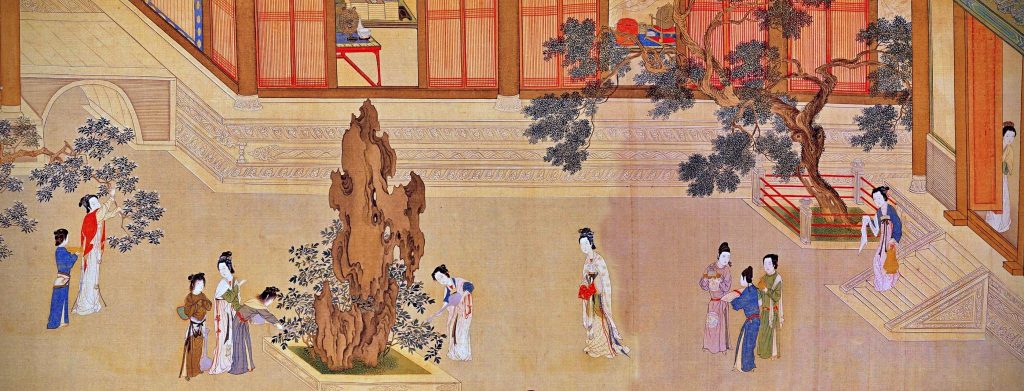

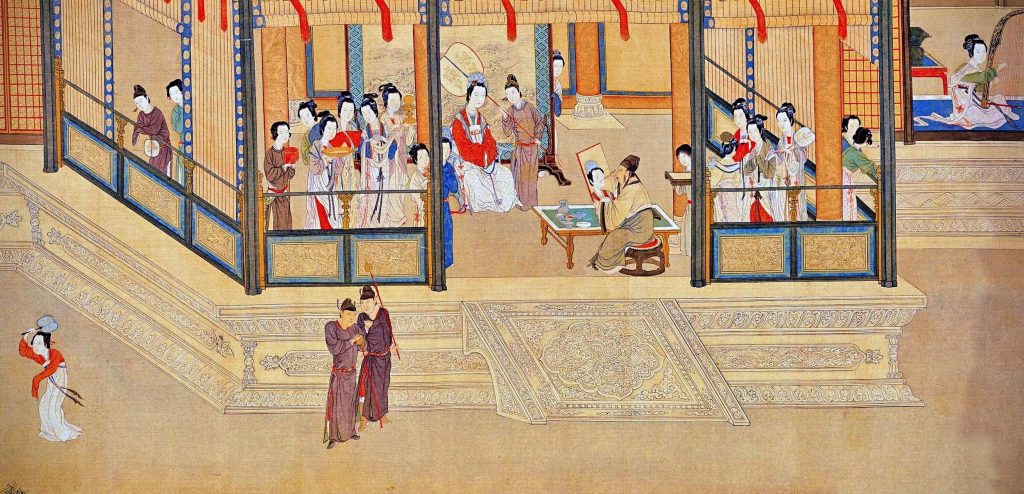

The artist featured court ladies in his works and drew inspiration from the past. For example in Spring Dawn in the Han Palace he imagines the court ladies in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) palace. The handscroll opens with the palace gates and then leads us through sumptuous courtyards. Here, elegant ladies engage in various leisurely activities. You can see one lady leaning over the rails with her children to watch the fish in the lake. Two peacocks impatiently wait for their meal as a lady tosses food at them.

Qiu Ying was skilled at describing building structures and furnishings. He accurately represented architectural elements as well. He modeled ladies’ dresses after those of the Tang and Song dynasties. However, their bodies are slenderer and more delicate, which was an image of feminine beauty recognized in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In another scene, the court ladies play a game of weiqi or Go, an ancient Chinese board game. To the left, some prepare a roll of woven silk, while others are weaving a tapestry. You can also see a mother playing with her two children.

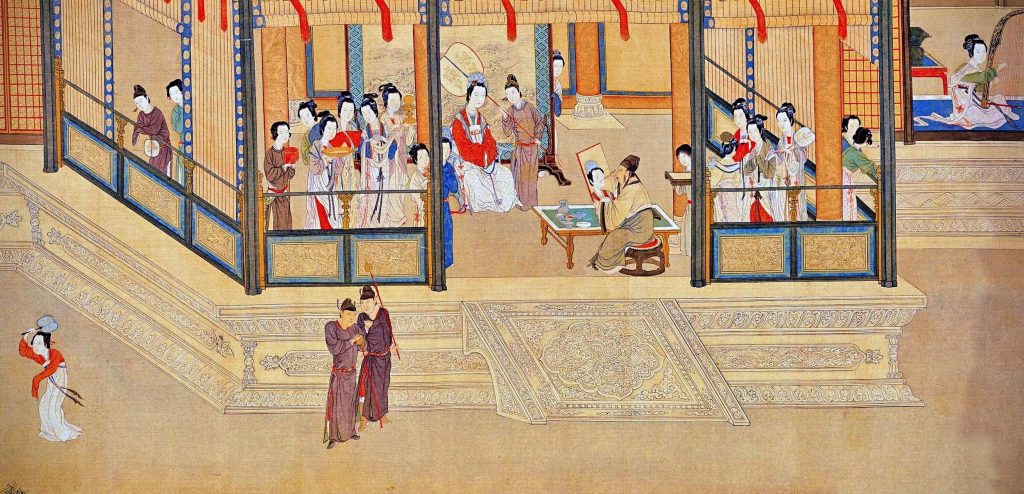

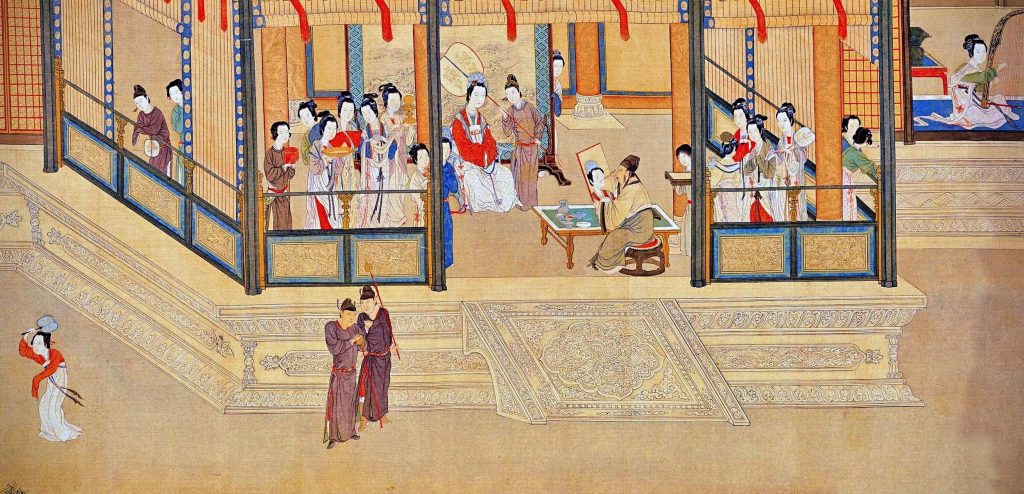

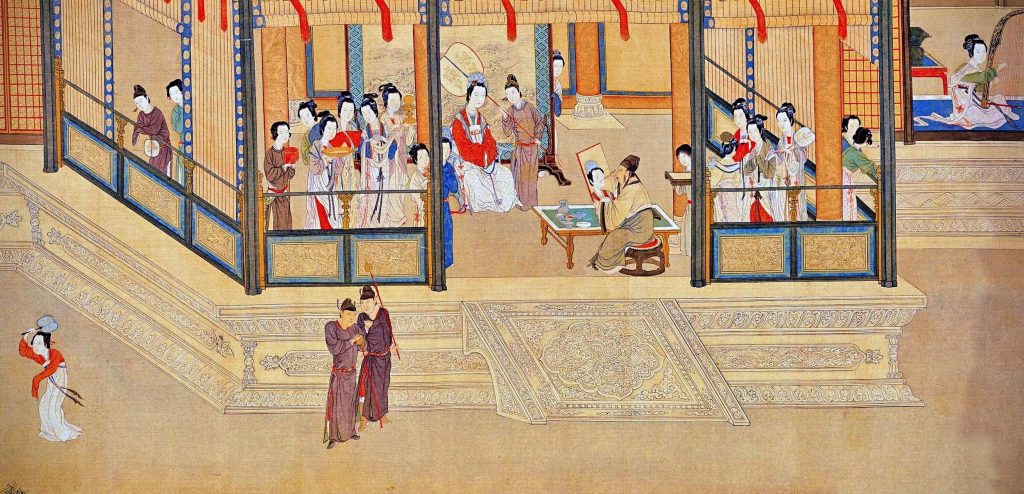

These depictions present a harmonious court life. However, court life also had a more competitive side. For example, Qiu Ying painted a narrative depicting the concubines of Emperor Yuan (75 BCE – 33 BCE). In ancient times, an emperor was presented with portraits of the women before meeting with them. This way he could decide whom to choose as a consort. Hoping to attract the emperor’s attention, court ladies often bribed court artist Mao Yanshou to paint them more beautifully than they actually were. But one lady, Wang Zhaojun refused to bribe the artist. As revenge, Mao Yanshou depicted her as ugly, with moles on her face.

In the painting, Wang Zhaojun sits in front of a screen while the artist paints her portrait. The other concubines are gossiping among themselves as they watch the painting progress. Two eunuchs in the foreground are talking with each other. They are aware of the bribes and Mao Yanshou’s deception.

After seeing Mao Yanshou’s distorted portrait, Emperor Yuan never visited Wang Zhaojun. Consequently, she remained a lady-in-waiting. However, one day, the ruler of the Xiongnu empire came to the Han court to establish a relationship through marriage. The emperor chose Wang Zhaojun as the bride, believing that she was the least attractive of his ladies. Only when she was summoned did Emperor Yuan realize that she was the most beautiful woman at court. It was too late though, and the offer had already been made. Enraged by Mao Yanshou’s deceit, the emperor ordered the artist to be executed.

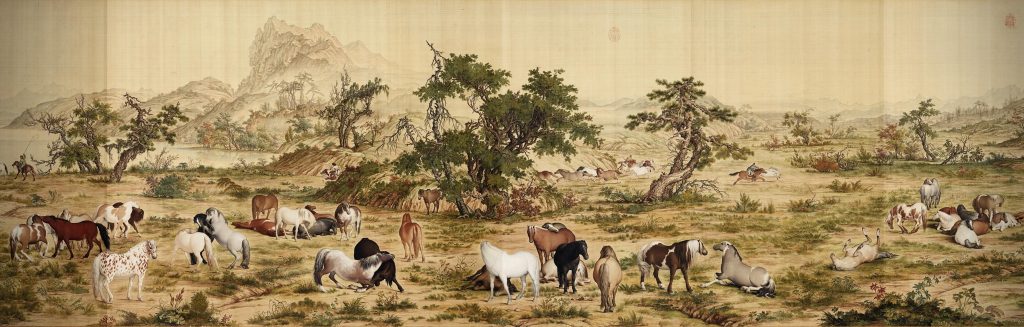

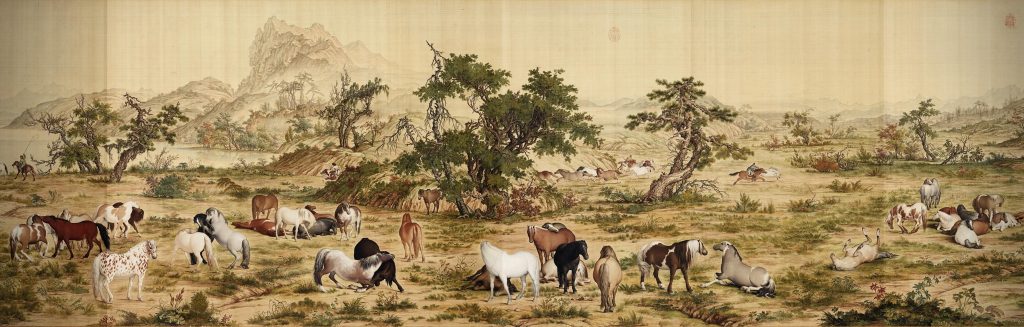

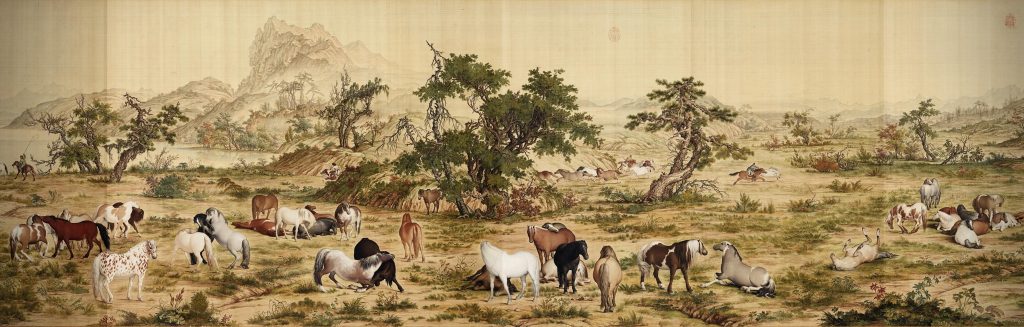

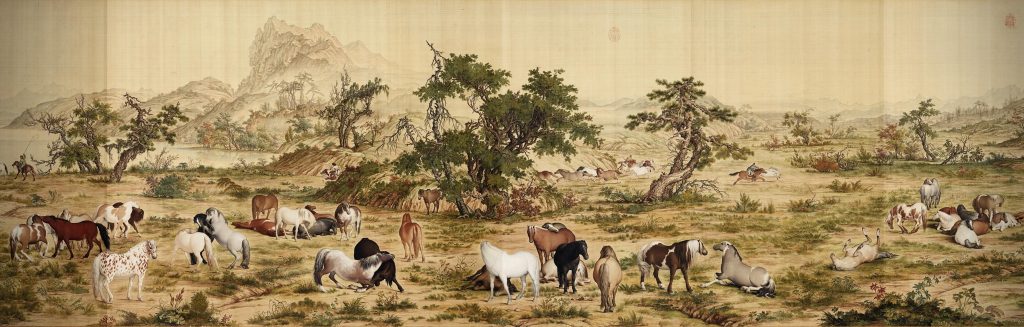

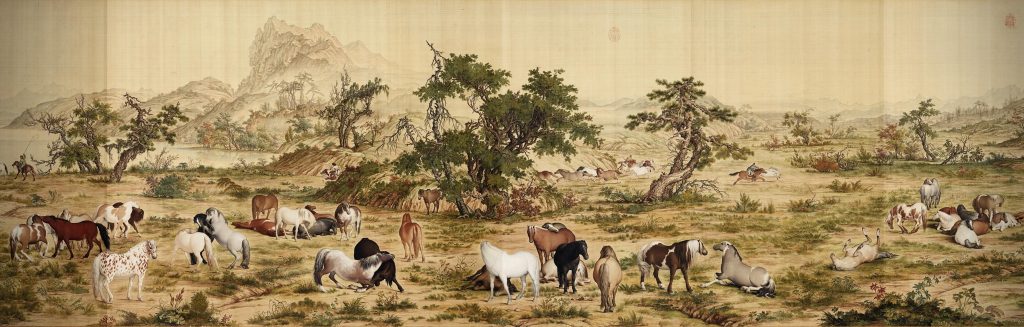

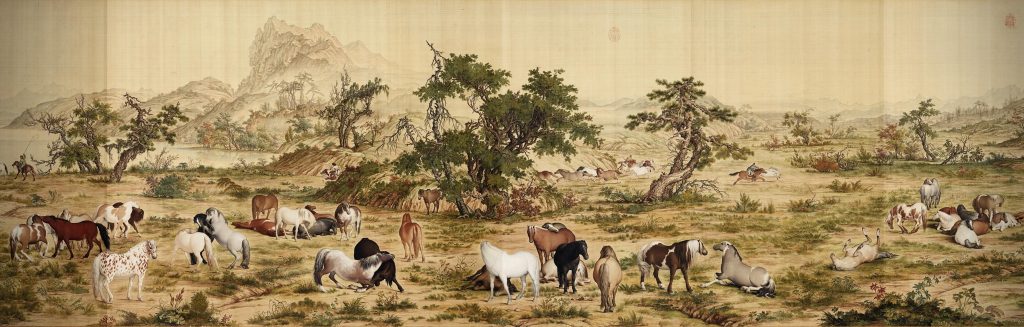

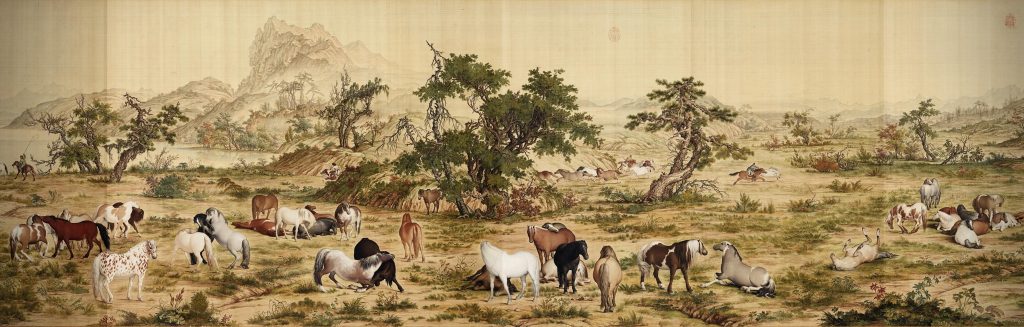

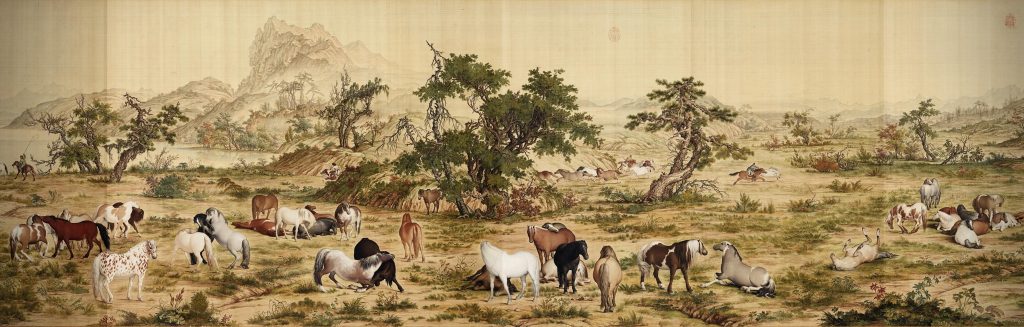

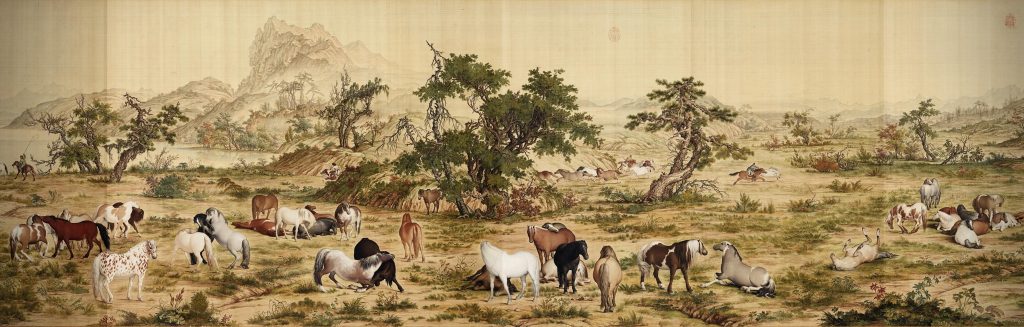

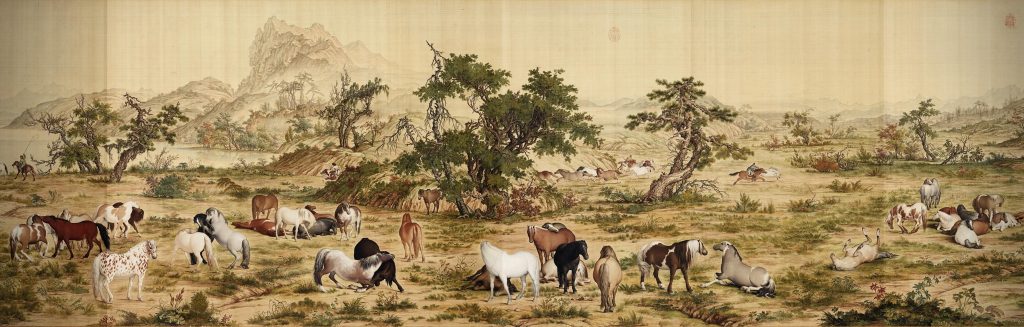

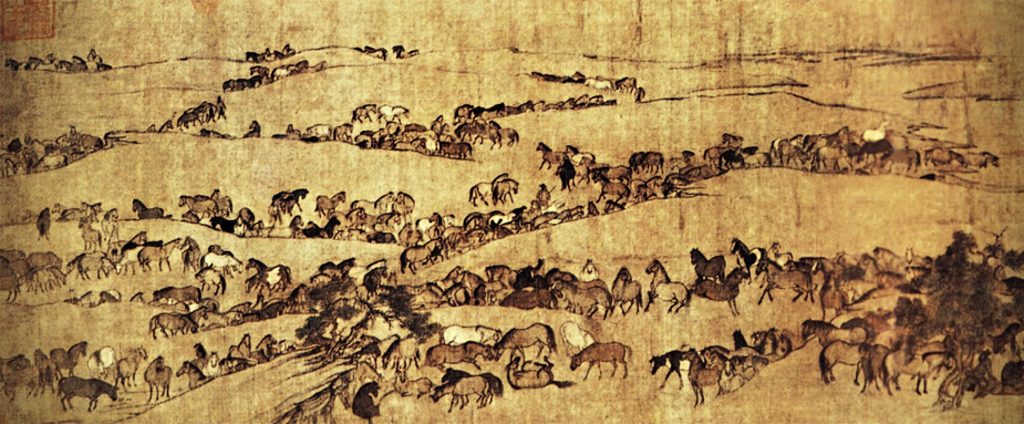

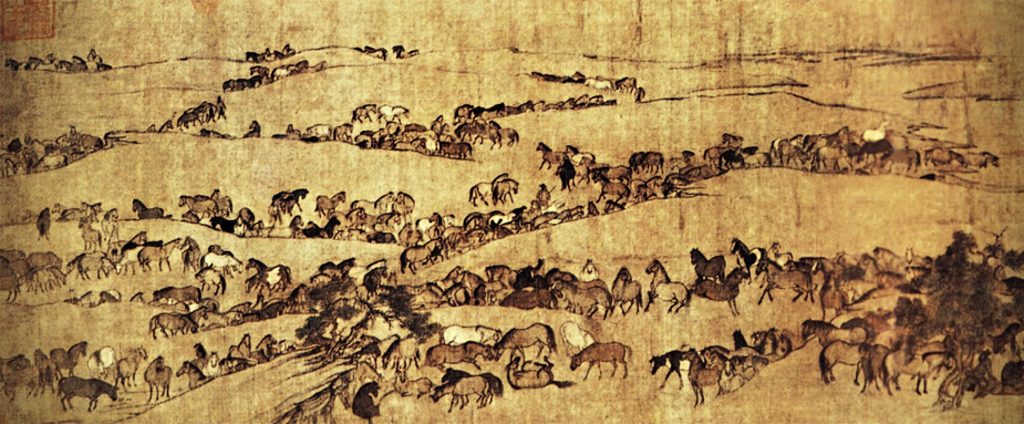

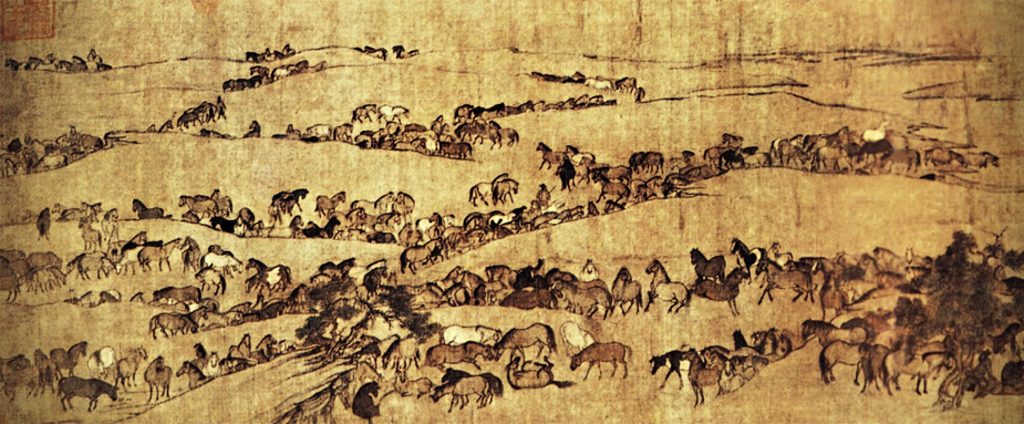

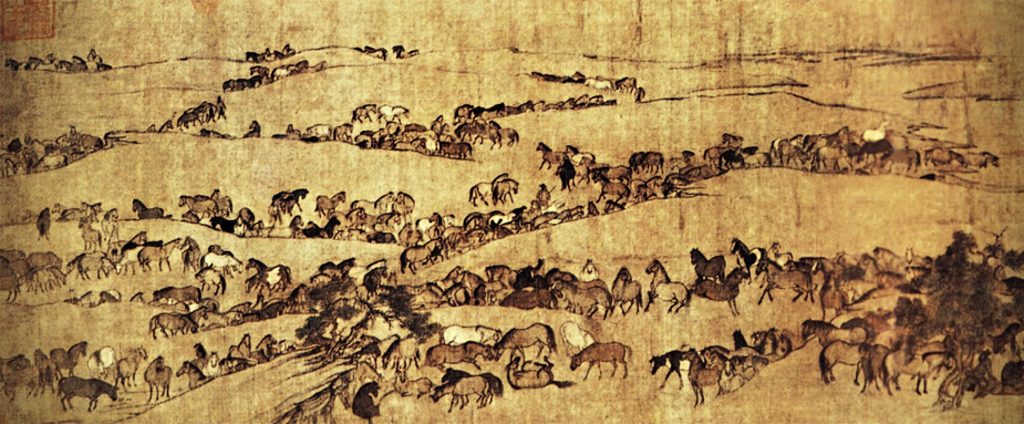

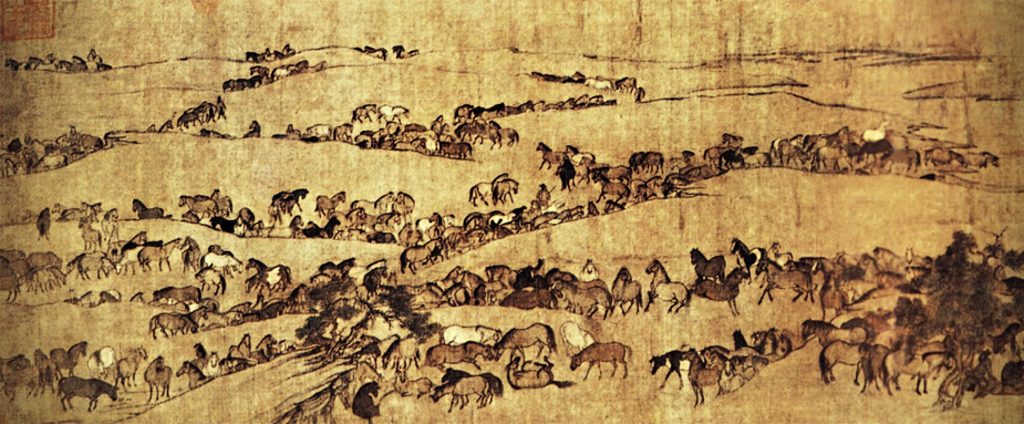

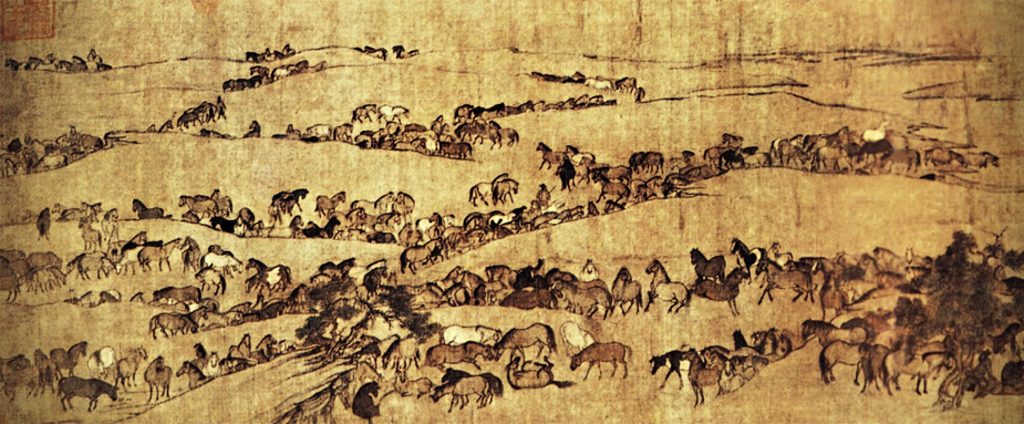

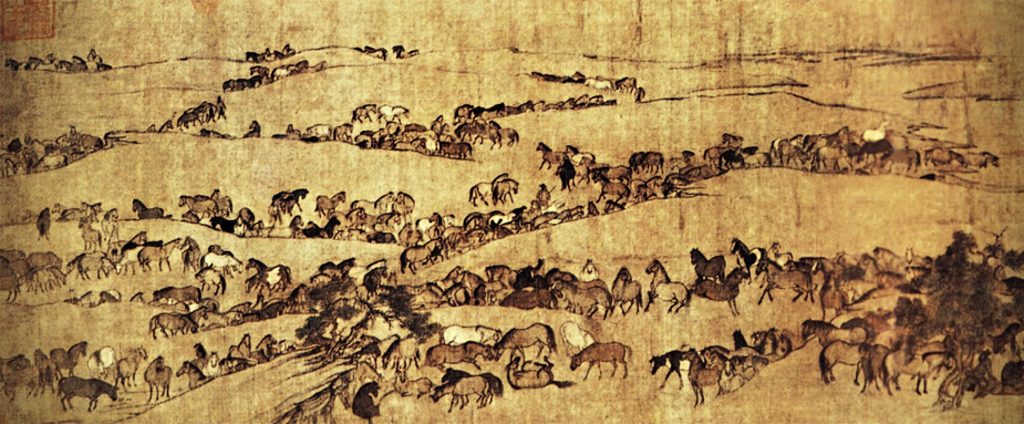

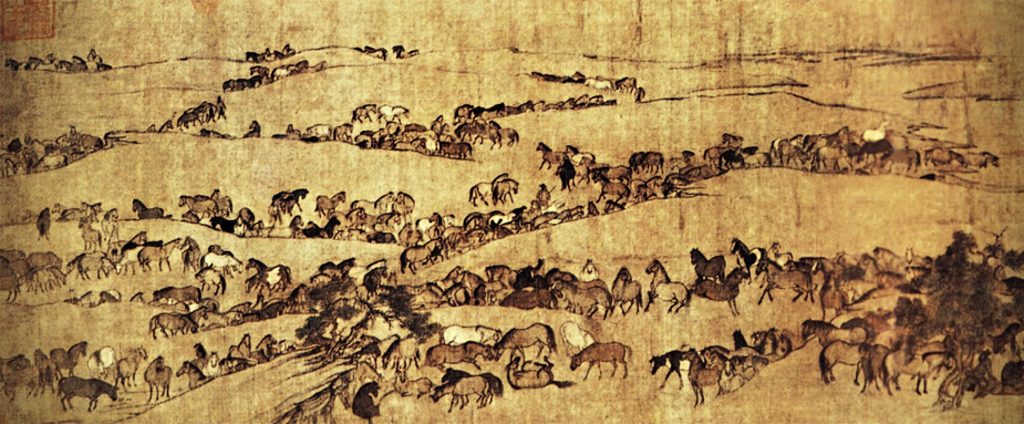

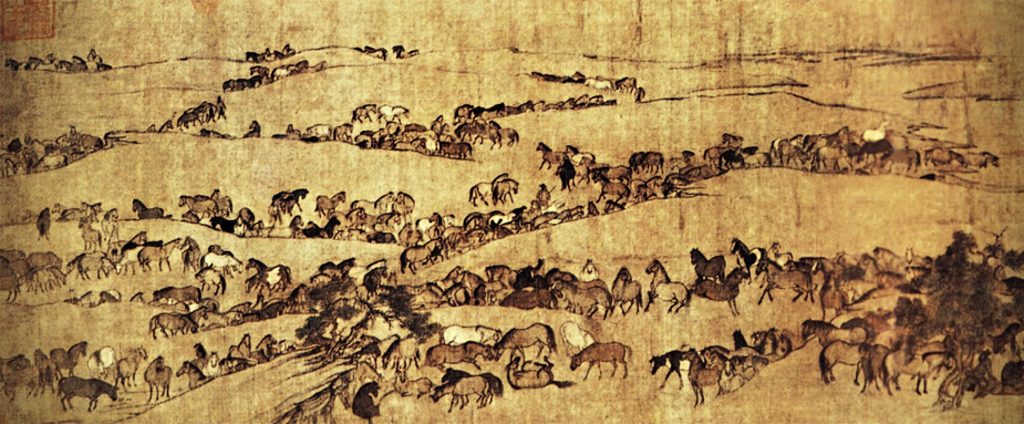

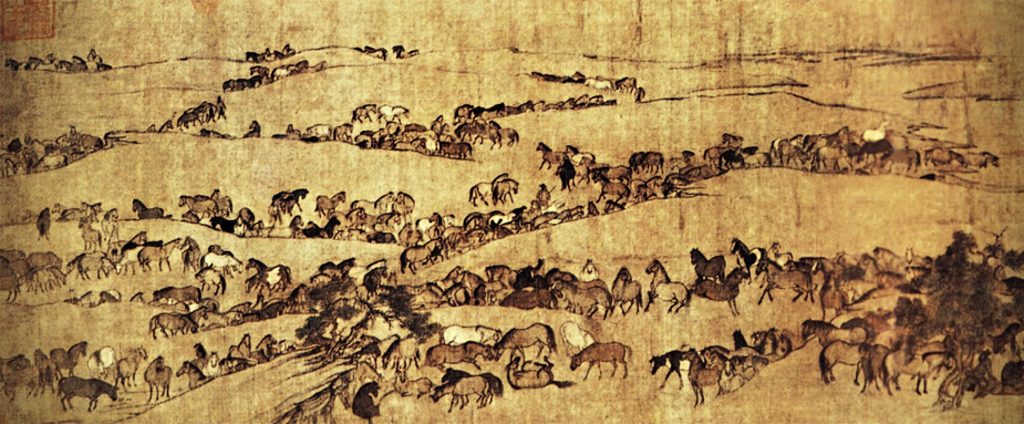

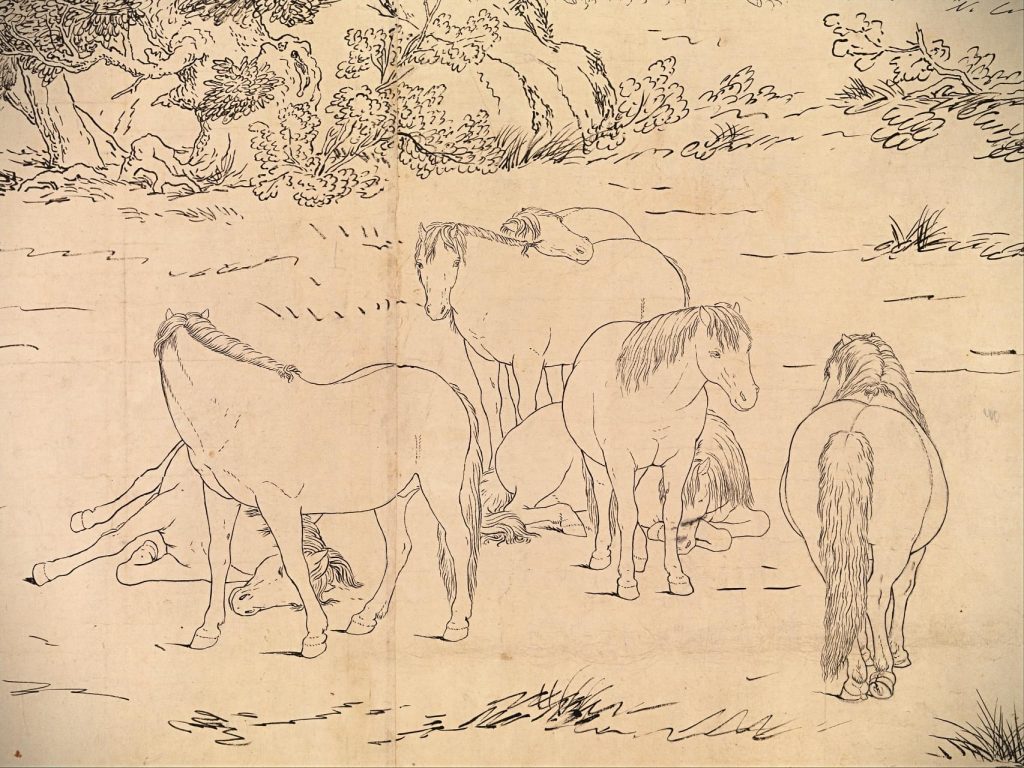

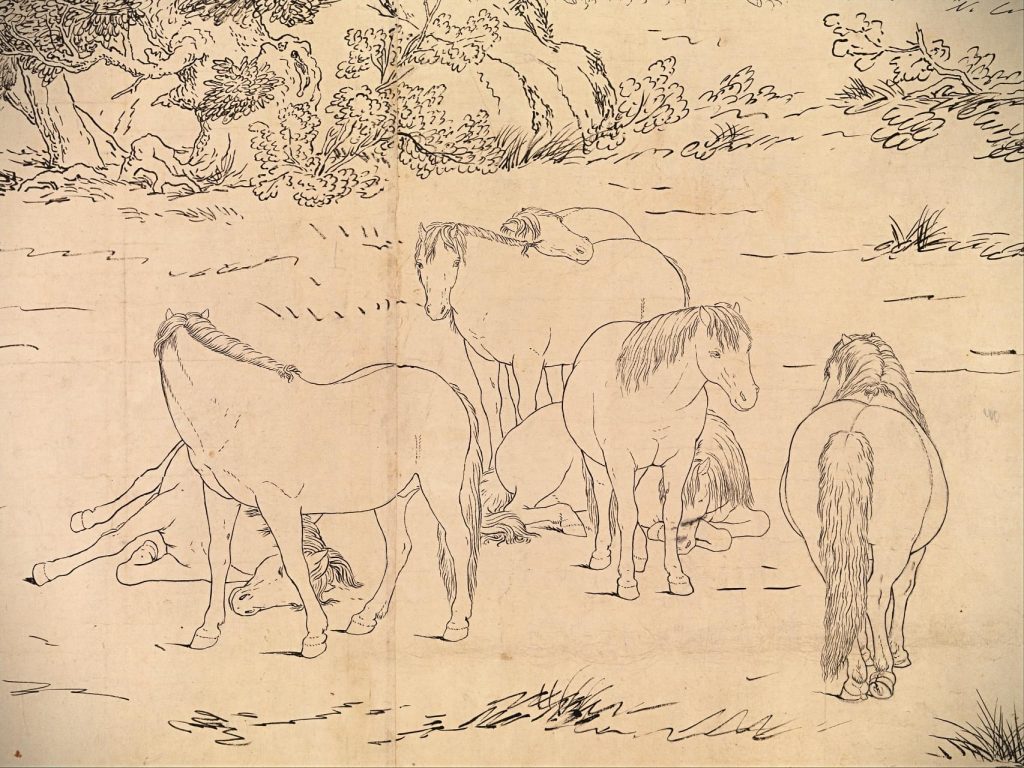

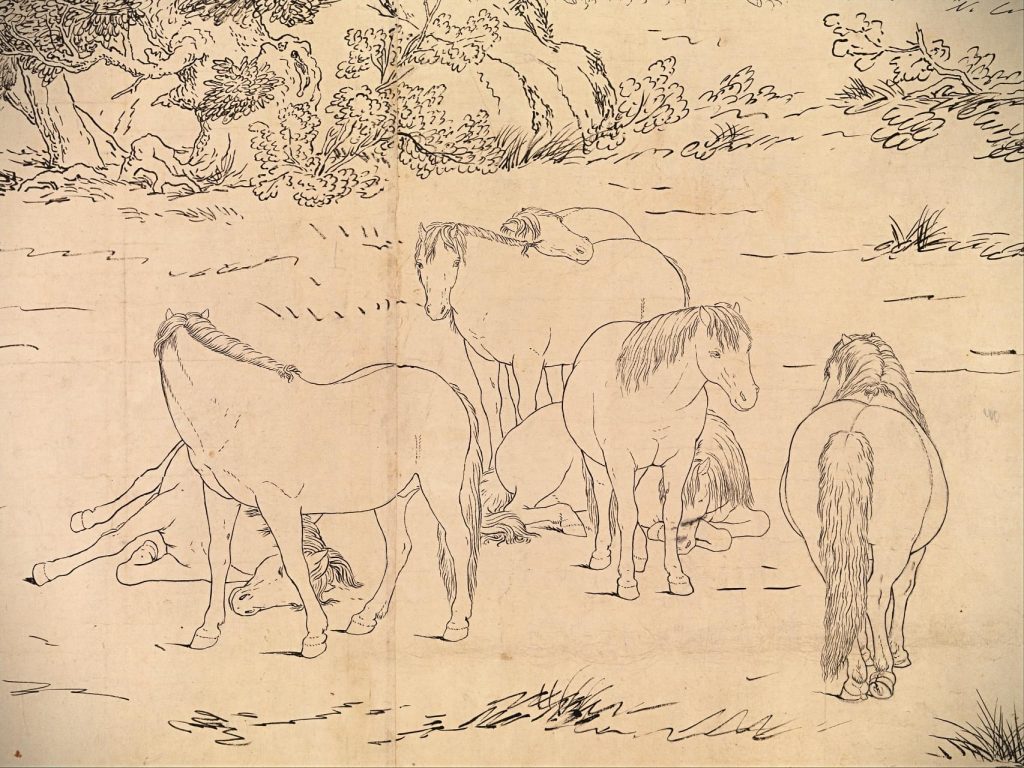

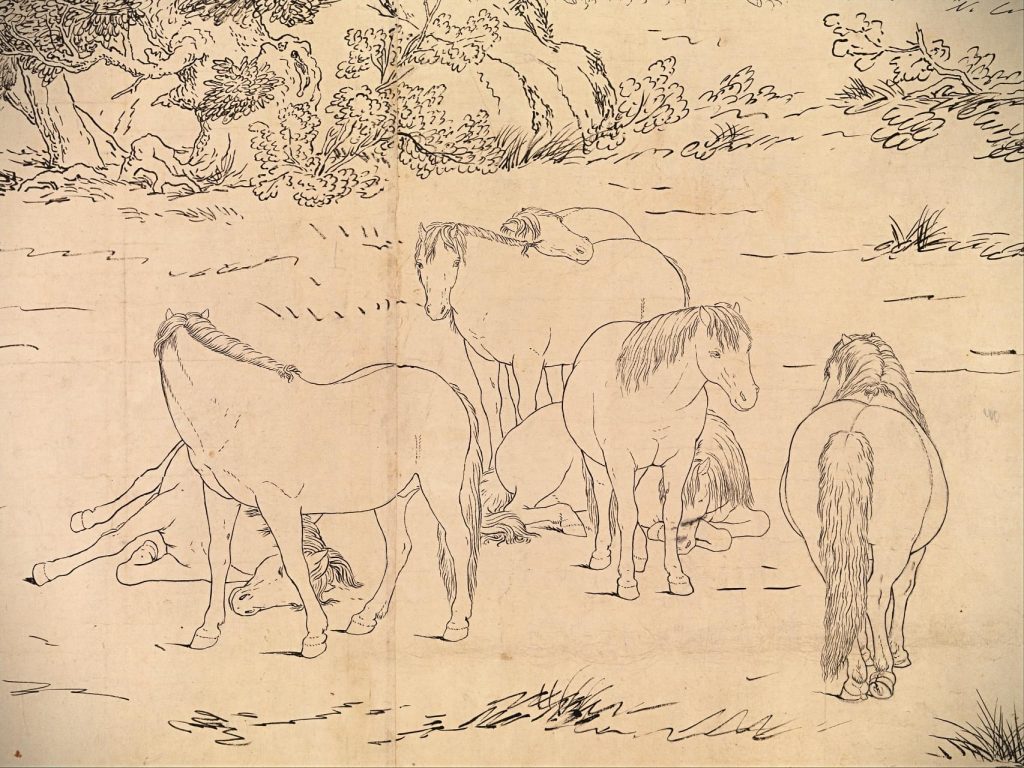

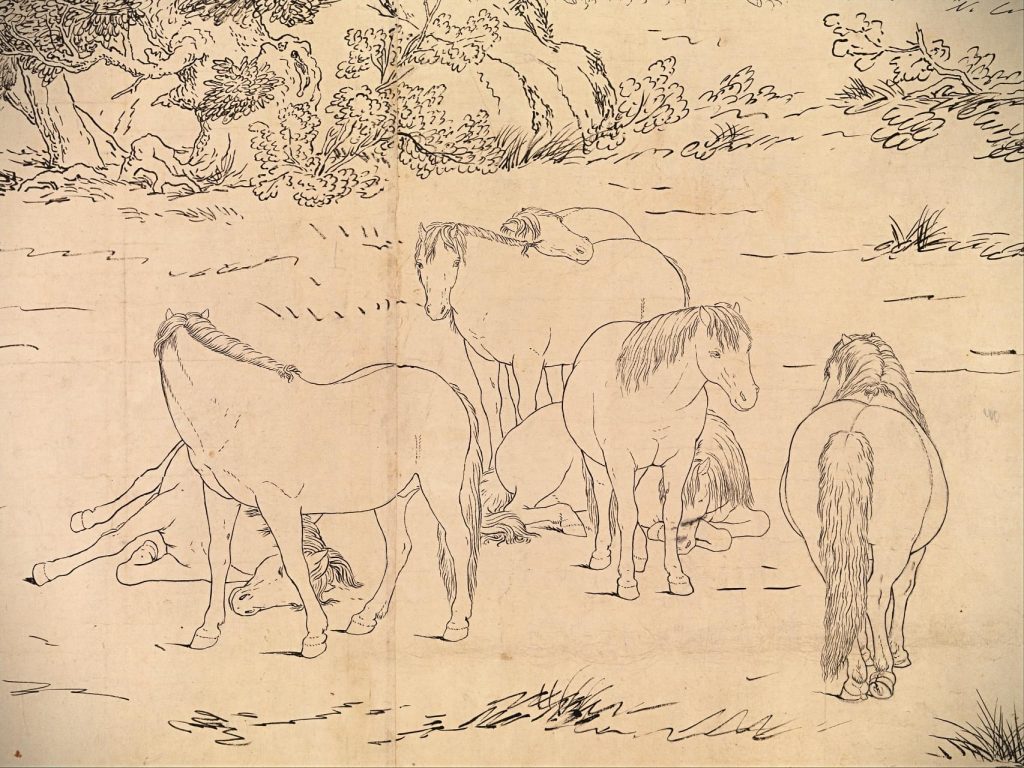

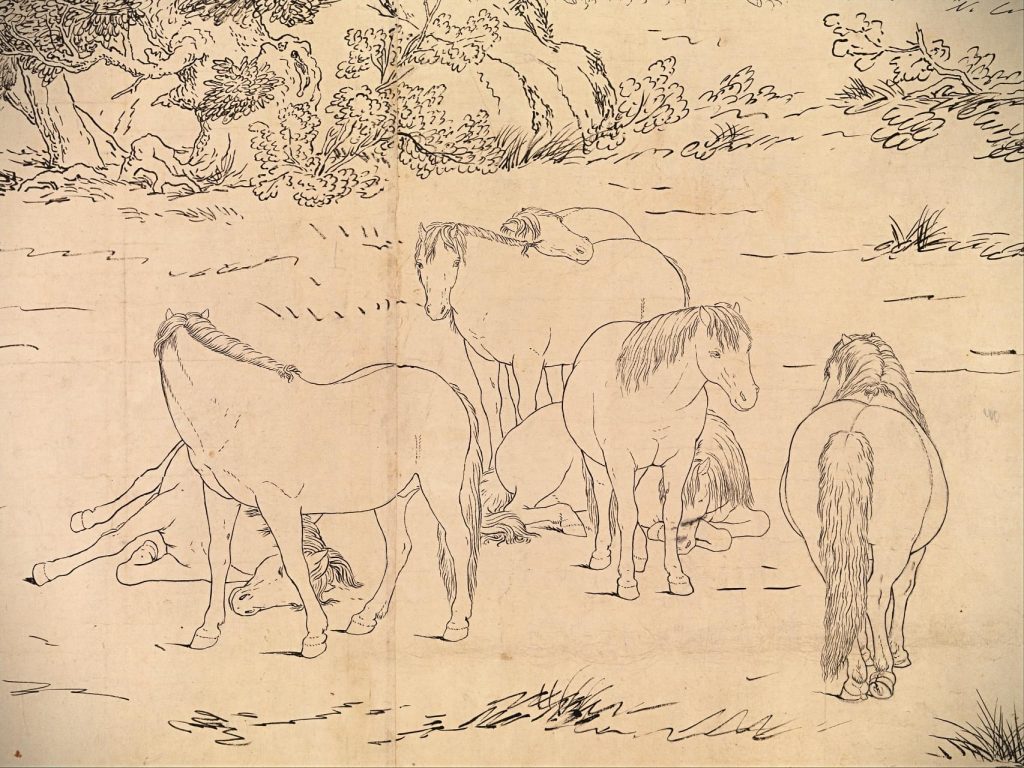

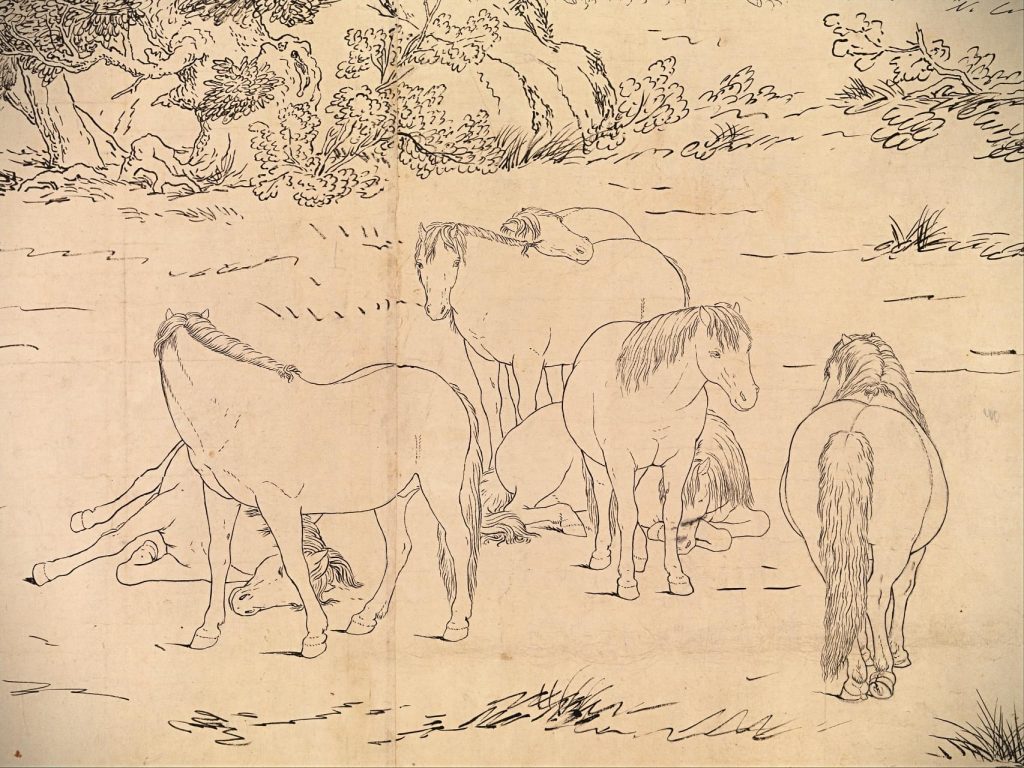

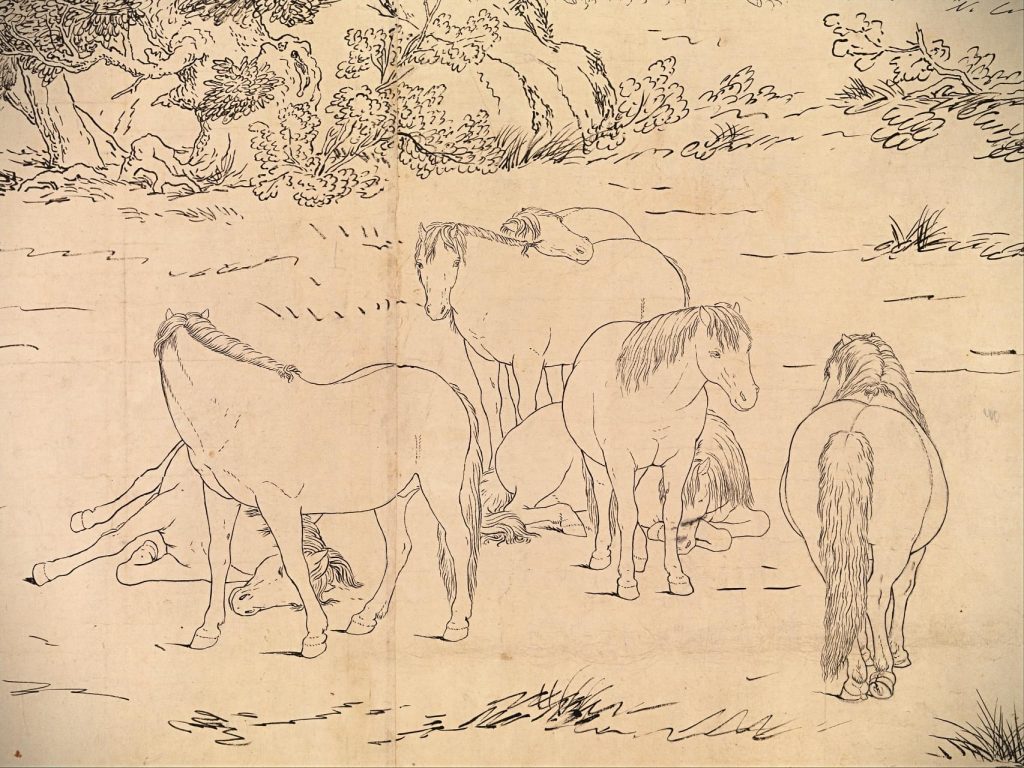

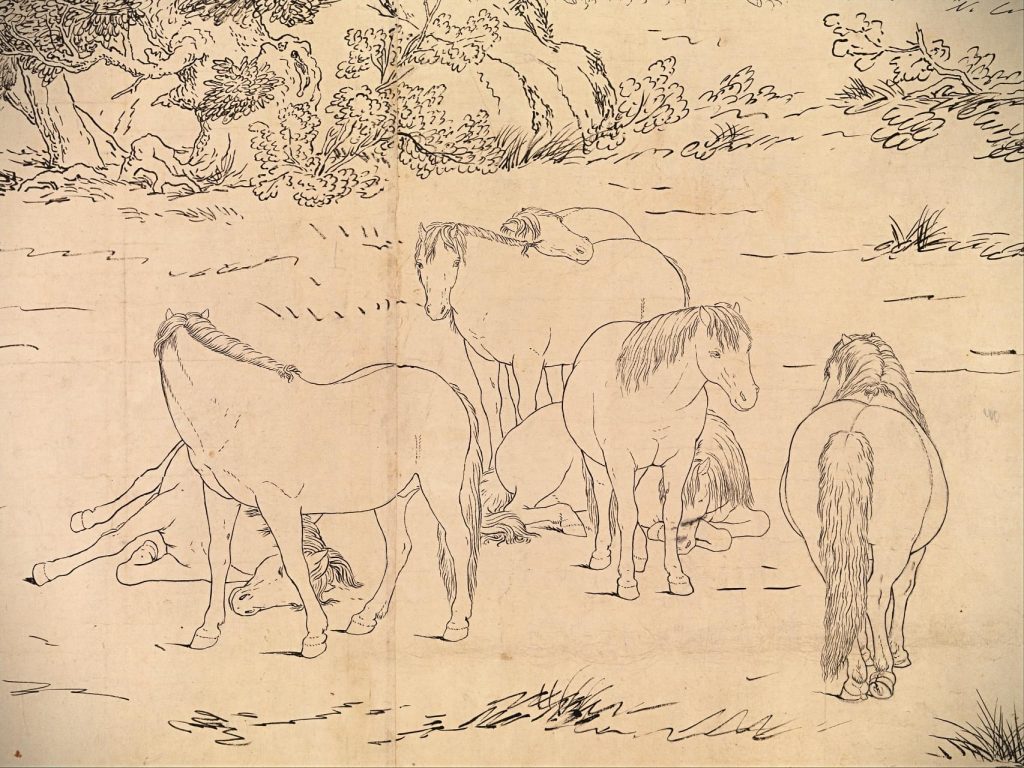

Another famous artwork is Giuseppe Castiglione’s One Hundred Horses. Castiglione (1688–1766) was a European artist who adapted his technique to Chinese aesthetics and served three Chinese emperors as court painter.

The artist was born in Milan and learned to paint under the guidance of a master. When he was 19 years old, he entered the Society of Jesus in Genoa. Although a Jesuit, he was never ordained as a priest, instead joining as a lay brother.

In 1715, Castiglione arrived in Macau, then reached Beijing and stayed at a Jesuit church. One day, Emperor Kangxi (1654–1722) came across one of his paintings. As a result, the artist was assigned a few disciples. In China, Castiglione became known under the name of Lang Shining. He served as an artist for three emperors: Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong. He adapted his Western painting style to Chinese themes and tastes. For example, strong shadows used in chiaroscuro were unacceptable in Chinese portraiture. Emperor Qianlong thought that shadows looked like dirt. Therefore, when Castiglione painted the emperor, he diminished the intensity of the light so that there was no shadow on the face.

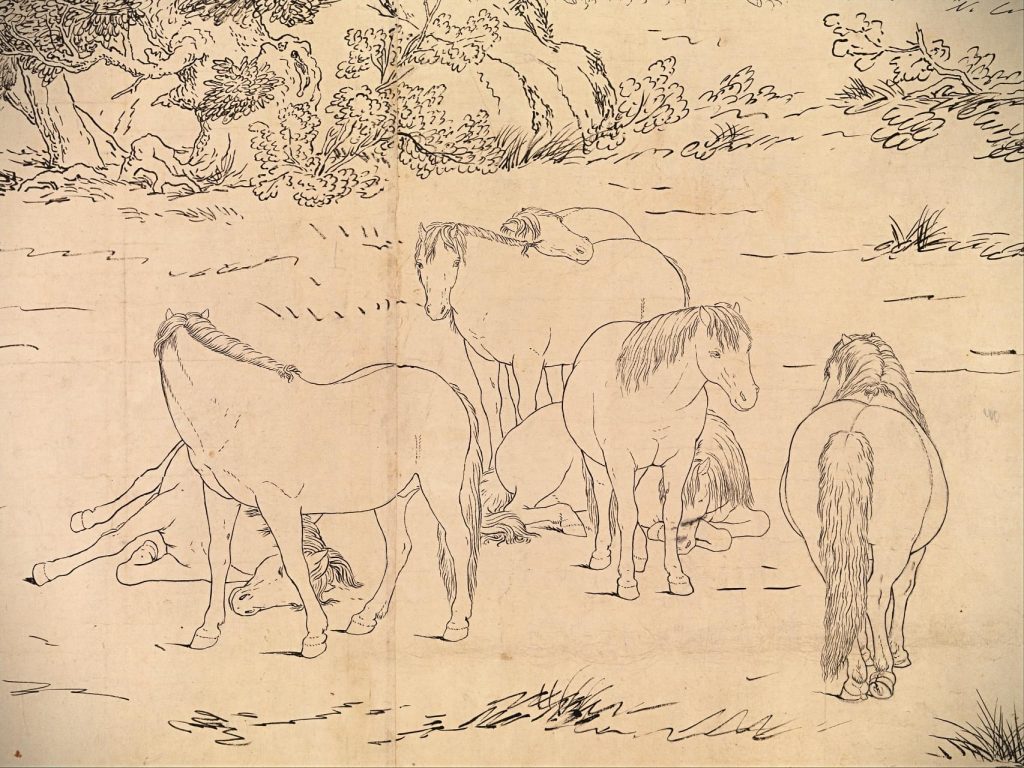

Castiglione executed his One Hundred Horses in the form of a Chinese handscroll of nearly eight meters in length. He painted it largely in a European style. Nevertheless, here too Castiglione reduced the dramatic chiaroscuro shading. There are only traces of shadow under the hooves of the horses. You can also see some of the horses are in a “flying gallop” pose that was not conventional in European paintings.

The horse played an important role in the life of the Chinese people. As a result it has a special place in Chinese art. You can see how Li Gonglin (1049–1106), a Chinese painter, inspired Castiglione to create this work. For example, some horses disperse into different groups, some grazing on the meadow, some chasing each other, and some rolling on the ground. The horses are all vividly outlined, making the scene lively and idyllic.

Most of Castiglione’s works are painted in tempera on silk, and thus he had to adapt to the Chinese style of working. Painting on silk does not allow for corrections. Therefore, Castiglione had to work out every detail on paper before transferring the idea to silk.

Castiglione depicts horses swaying on the grass or frolicking near each other, just as in Li Gonglin’s painting. Figures are often shown foreshortened. Although he paints trees in the traditional Chinese style, the artist uses shading. But the contrast between light and dark is minimized.

You can see three horses have already crossed the river while others follow behind them. Some horses are quenching their thirst by the river. More are resting quietly, frolicking with their young offspring. In Chinese art, horses represent speed, endurance, and victory. Certain trees also signify different ideas. For example, the oak is a symbol of masculine strength. You can see the willow tree which is a Buddhist symbol of humility. The pine tree signifies longevity and resilience. Finally, red maple leaves almost always convey the autumn season.

The palace art of the Qing dynasty already showed traces of European influence. However, Castiglione’s use of perspective, light, and shadow helped to refine a style that combined Western techniques with the aesthetics of Qing art. Thus, Castiglione’s depictions of horses became one of the most famous artworks in China.

And we will live like horses

Free rein from your old iron fences

There are more ways than one to regain your senses

Break out the stalls and we’ll live like horsesThe Big Picture (Elton John album), Live Like Horses lyrics, 1997.

Live Like Horses (Live)

Watch the animated One Hundred Horses by the National Palace Museum.

Watch an animated version of the scroll Along the River During the Qingming Festival.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!