5 Unconventional Materials in Contemporary Art

Contemporary sculpture long ago broke free from classical forms and traditional aesthetics. More and more often, artists choose nondurable,...

Zacheta 18 December 2025

29 January 2026 min Read

Kent Monkman has risen to become one of the most important figures in the contemporary art world. A Cree artist and author currently based in Toronto and New York City, his art practice for the past three decades revolves around the experiences of Indigenous peoples, particularly on Turtle Island (the Indigenous name for North America). Monkman shifted from abstract to representational art in the early 2000s, which shaped him into the artist he is today. Follow along on his art journey through five selected paintings.

Throughout Monkman’s works, viewers can encounter a recurring character across different media and periods—Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. She is the artist’s gender-fluid alter ego, who has evolved since she made her debut in Study for Artist and Model (2003) wearing high heels. Miss Chief’s ability to time-travel and shape-shift plays a crucial role in Monkman’s oeuvre. She garners everyone’s attention and retells the history written by European settlers, and she is always present, even though she sometimes drifts from her usual form.

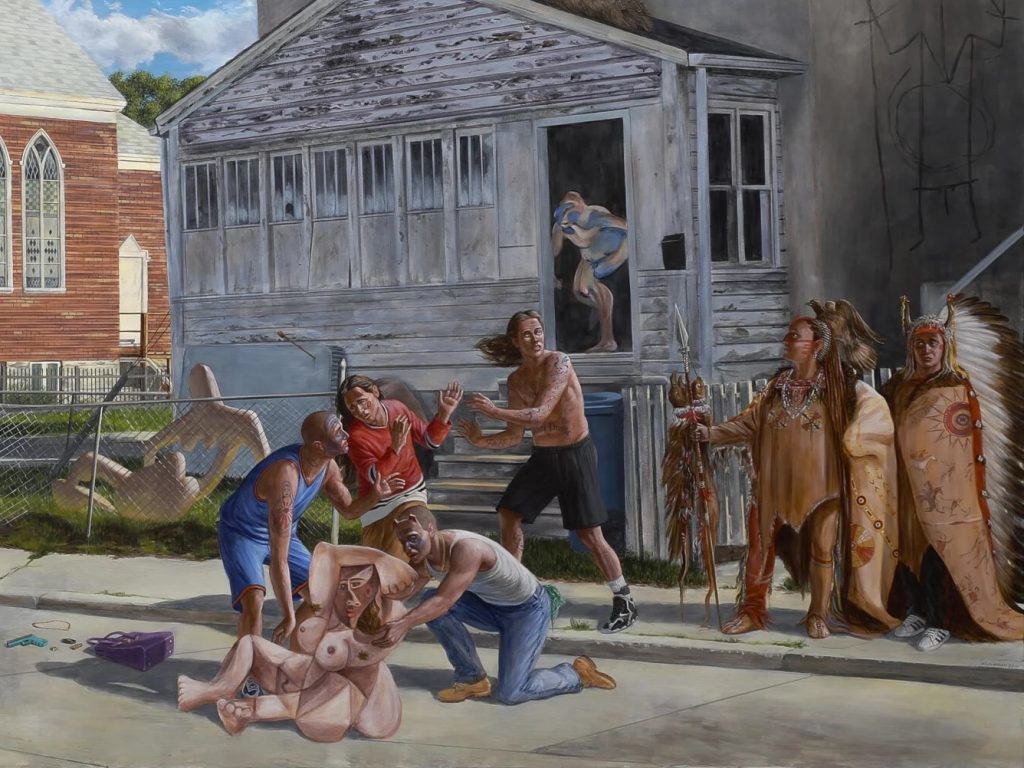

Kent Monkman, Death of the Female, 2014. Artist’s website.

Death of the Female is part of Monkman’s Urban Res series created from 2013 to 2016. In this series, he moved his focus from natural landscapes to urban scenes to shed light on the reality of life outside reserves. Monkman grew up in the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, where he learned of the stark contrast between the majority of the urban Indigenous population in the city’s North End and the middle-class neighborhoods occupied by the Anglo-Saxon population. Death of the Female depicts the corner of Chambers Street and Alexander Avenue in Winnipeg. A generic, run-down 2.5-story house sits next to a Salem Community Bible Church, the latter pristine by comparison. They form the backdrop of the scene.

Four young Indigenous men help a naked woman who appears to have been assaulted by a driver fleeing the scene in a black Sedan. Monkman’s Picasso-esque rendition of the woman and the driver is suggestive of a deliberate Cubist style that emphasizes the ongoing violence against Indigenous women and girls in North America. Monkman uses Picasso’s distortion of female nudes as a way to address the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit, and gender-diverse people (MMIWG2S+).

Kent Monkman, Death of the Female, 2014. Artist’s website. Detail.

Zooming out from the centre of the image, a couple of traditionally dressed and tattooed Indigenous men stand observing the incident from the side. There is a glimpse of Western influence in one of the men’s outfits—a pair of jeans and Adidas sneakers. This element is even more apparent in the younger men who are helping the woman, as is the Christian conversion suggested by their tattoos.

The coexistence of Indigenous and Western culture, religion, and values in the artwork closely reflects the lives of urban Indigenous peoples. Other signs of the clash between the two can be found through a sniper in a ghillie suit on the roof of the house, facing Columbia (the female personification of the US) in the sky above the church, who is, in turn, shooting arrows at him. Columbia is also known as the Angel of Progress, a personification of Manifest Destiny. She stands for the 19th-century belief that the expansion of the United States across America was justified and ordained by God. Death of the Female exemplifies Monkman’s art practice. His layers upon layers of iconography serves to examine both historical and contemporary social issues.

mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) is a diptych commissioned by The Met in 2019 for their Great Hall. Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People greeted visitors to the museum over the 17 months, from December 19, 2019, to April 19, 2021.

Welcoming the Newcomers depicts a scene of Europeans and their slaves arriving on Turtle Island. Along with them, they brought their religions, slavery, and pests. An array of Indigenous figures depicted was reappropriated from historical artworks from the Met collection, such as Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe (1770), Eugène Delacroix’s The Natchez (1823–24 and 1835), and Thomas Crawford’s Mexican Girl Dying (1848). This choice reclaims the sitters’ stories told by non-Indigenous artists, which is Monkman’s signature trope. On top of that, there is one central character who looks right back at the audience—Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. Her acknowledgement of the viewers is a signal for reflection and history being rewritten. She makes us face the facts that society has been afraid to disclose and rectify.

The other part of the diptych, Resurgence of the People, tells a story of Indigenous peoples keeping their tradition and culture alive while adapting to the new world built by settlers—beaded jewelry worn by many, as well as crosses around some people’s necks and jeans. People of diverse ethnicities sit on the boat with life jackets on. They are saved by the Indigenous peoples and their generosity. The scene implies a future of inclusivity without discrimination. The people featured are bracing through waves towards a bright future ahead, led by Miss Chief.

This is Monkman’s revision of the 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze. Monkman’s version of the story is against conquer and destruction. Instead, Miss Chief guides and embraces everyone to Turtle Island.

Kent Monkman, The Escape, 2022. Artist’s website.

Some of our awâsisak got away—they knew the bush and had help from the mêmêkwêsiwak. But so many of our children did not come home. We hold those children in our hearts always.

Kent Monkman, Gisèle Gordon, The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island, vol. 2, McClelland & Stewart, 2023, p. 96.

A young Indigenous girl in traditional clothing made of tanned hide and moccasins hushes mêmêkwêsiwak (little people who are sacred beings) beside her. She appears to be hiding from an officer in a Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) uniform, standing at a far distance in the background. A woman beside the officer is leading him away.

The Escape shows the painful history of residential schools in Canada. For over a century, tens of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families to residential schools. They would be striped of their Indigenous identity and converted into Christians, like the denominations and the government supporting those schools expected.

Monkman shares a glimpse of what may have happened when officers forced children into what he calls “work camps.” He has created several paintings that address the historical trauma that these so-called institutions have inflicted on Indigenous peoples. These works serve as both a reminder and proof that this history must be remembered, and also as a catalyst for reconciliation.

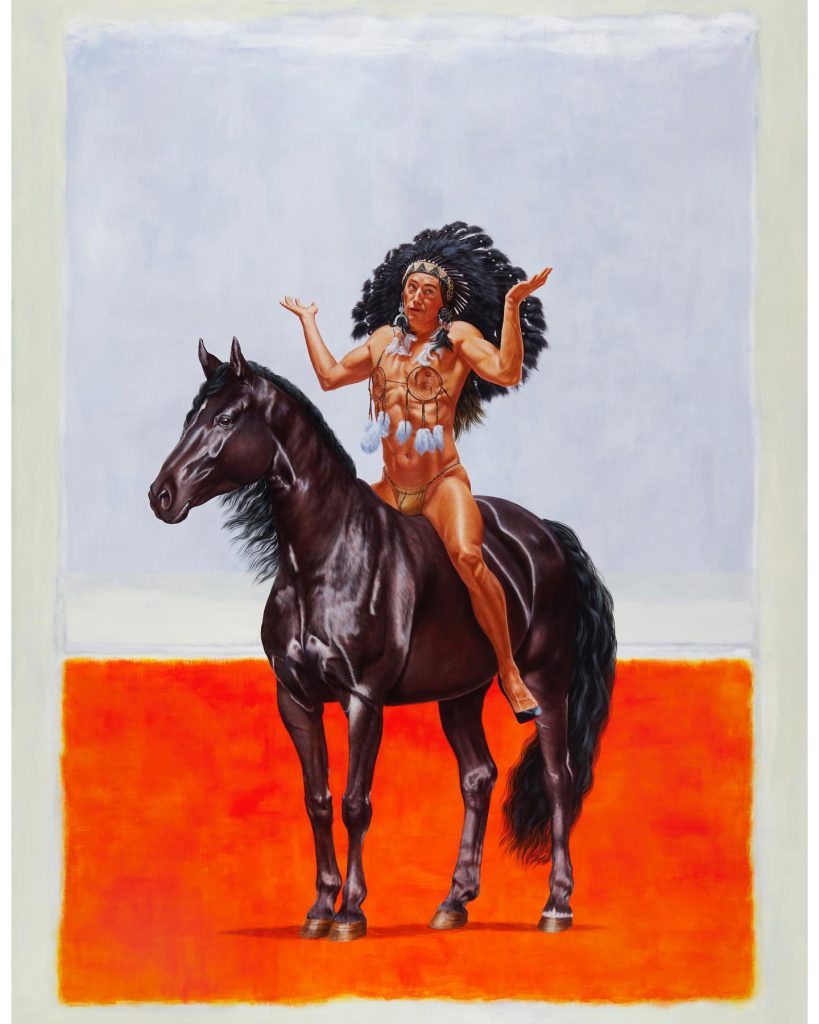

Kent Monkman, The Great Mystery, 2023, Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, NH, USA. Artist’s Instagram.

Monkman’s The Great Mystery was commissioned by the Hood Museum of Art and was part of the 2023 exhibition of the same title. It was inspired by two artworks from the museum’s collection. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle appears once again on horseback, placed against an abstract background that reinterprets Mark Rothko’s Lilac and Orange over Ivory (1953). The piece also reimagined Cyrus Dallin’s bronze sculpture Appeal to the Great Spirit (1912)—where you can find a similar Indigenous figure on a horse with arms open toward the sky.

Monkman explains that the Cree concept of mamahtâwisiwin (unknowingness) is heightened through the interplay of these two well-known works by settler artists. Viewers are invited to consider the idea of subconsciousness embedded in Color Field painting alongside the notion of the “vanishing race” promoted by European settlers, inlaid within the bronze sculpture, with Miss Chief at the centre of it all. The work becomes a cheeky wink at the vanishing race narrative created by European colonists.

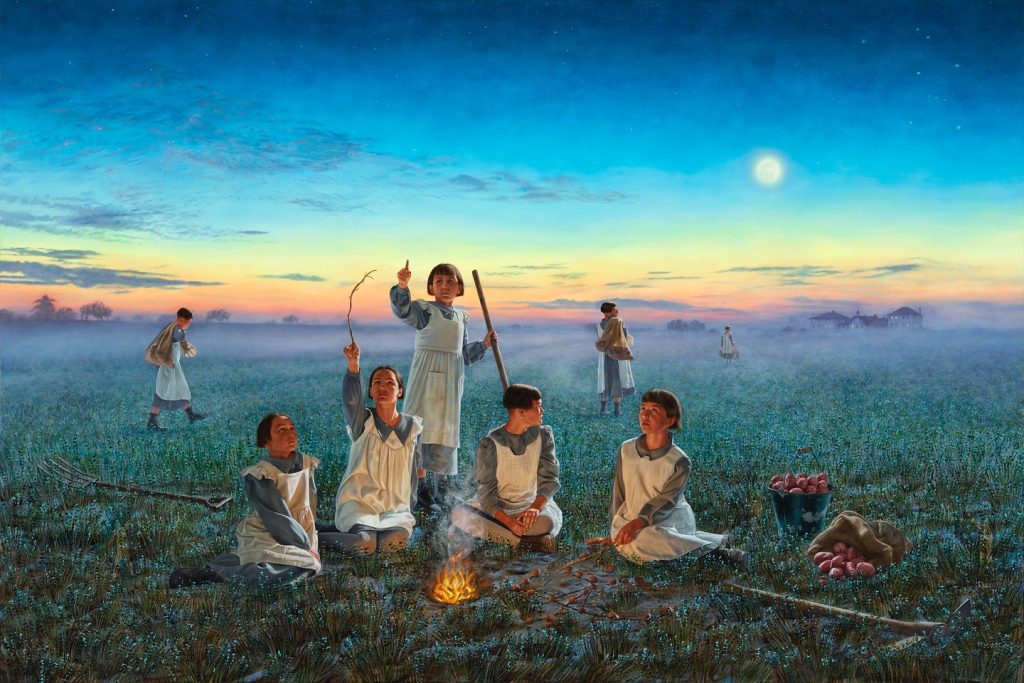

Kent Monkman, kîwêtin acâhkos (The North Star), 2025. Artist’s website.

kîwêtin acâhkos (The North Star) is a painting that is part of Monkman’s latest series, Knowledge Keepers that highlights the resilience of residential school survivors. The dramatic lighting created by a bonfire and the sunset captures viewers’ attention. The girls’ facial expressions, despite the scenery, are solemn. And their eyes look toward the sky, seemingly searching for the stars they remember from stories shared before they were taken away.

The girls, all dressed in residential school uniforms, gather around the fire. A few of them are in the background working and walking toward the school in the distance. One of the girls sitting by the fire is making a constellation out of twigs and potatoes that they were forced to harvest. On their side, the artist places future elders, pointing and looking toward the stars—to safeguard traditional knowledge, and to make sure that it remains with them.

Monkman’s paintbrush brings back to life the tragic history of residential schools. It is a story that continues to impact many Indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States (where they are called American Indian boarding schools). This series, in particular, foregrounds the children who never came home, as well as the voices of those who survived the horror.

Kent Monkman in his studio in New York. Photograph by Aaron Wynia. Art21.

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle’s story is still ongoing. In the two-volume book The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island, written by the artist and his long-time collaborator Gisèle Gordon, Monkman offers a different version of the history of Turtle Island through Miss Chief’s eyes—one that challenges the narratives many people learned in school.

Through painting, performance, and storytelling, Monkman insists that history is not set in stone but bound to be rewritten, contested, and reclaimed. Miss Chief, as a time-travelling and shape-shifting presence, reminds viewers that the past is inseparable from the present, and that acts of remembrance are also acts of resistance.

Kent Monkman’s work can currently be viewed in Kent Monkman: History Is Painted by the Victors, on display until March 8, 2026, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal, Canada.

Artist’s website. Accessed: Jan 5, 2026.

Mark Rothko, Museum of Modern Art. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People): Welcoming the Newcomers, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

The Great Mystery, Hood Museum of Art Online Collection. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

Shirley Madill, Kent Monkman: Life & Work, 2022, Toronto: Art Canada Institute. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

Kent Monkman and Gisèle Gordon, The Memoirs of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle: A True and Exact Accounting of the History of Turtle Island, Vol. 2. 2023, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Marco Muller, “Death of the Female: Interpretations of Iconography through the Lens of a Winnipeg Cree,” Artspace. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, A Knock on the Door: The Essential History of Residential Schools from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Edited and Abridged, 2015, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Andrew Woolbright, “Kent Monkman recasts history painting within a Cree worldview,” Art21. Accessed: Jan 16, 2026.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!