Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 10 June 2024

The last time that we talked about the Victorian era, we looked at steam travel, Alice in Wonderland, Romanticism, the Pre-Raphaelites and Sherlock Holmes. So what shall we look at next? How about the Gothic, Jack the Ripper, photography, zoological gardens, and the Victoria & Albert Museum to further build our visual picture of the Victorians and the world that they inhabited?

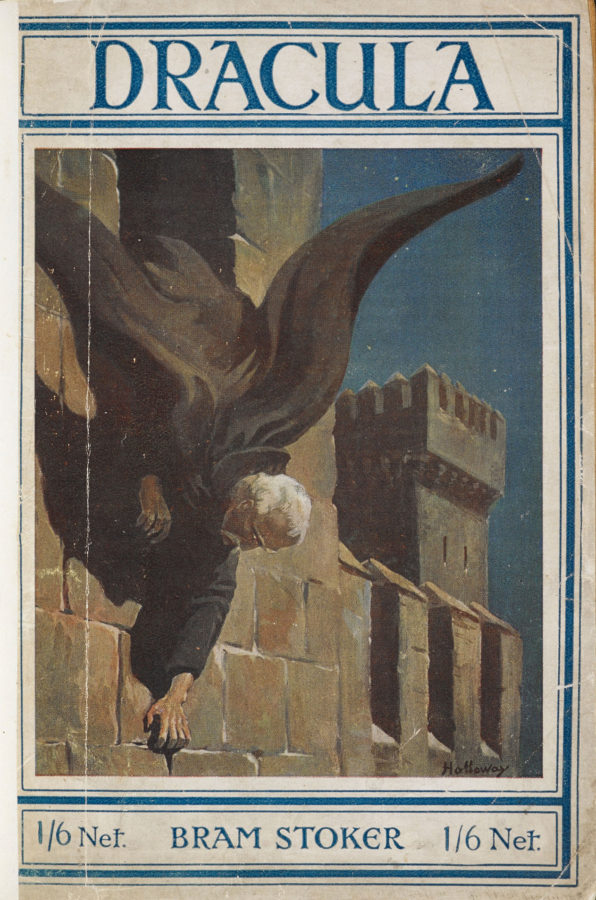

The Gothic in the Victorian Era was replete with strange writing, painting, and illustration. There is a raft of English Gothic literature for example that begins in 1765 with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, followed by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1818, and Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights in 1847 (the year of Bram Stoker’s birth). The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson was published in 1887 and of course, Dracula by Bram Stoker appeared in 1897. This is to name just a few! Dracula and Frankenstein are perhaps the most ingrained into universal consciousness, having been adapted for film and television more times than one can count.

The Victorians were fascinated by death, decay, and ideas of the supernatural. Therefore it makes sense that the literature and art of the era reflect this rather morbid interest. Decaying and gloomy locations, shrouded in mystery and riddled with labyrinthine corridors and moldering rooms provided perfect locations for intensely emotional and often violent stories in which ghosts, ghouls, and vampires were not uncommon. Brutal acts of savagery arising from extreme motives came across more effectively if they were presented in surroundings that mirrored their dark natures. This painting by Henry Fuseli entitled Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggers vividly expresses Gothic sentiments: Macbeth’s anguish is starkly written on his blanched face, Lady Macbeth’s determination is wild and aggressive, and the sordid nature of the murder of a King within the dark walls of their castle is realized in the sheer horror of the scene.

The Gothic isn’t only about the Victorians’ predilection for gory murders and dark deeds! It is also about the imagination and how it can distort reality. In the painting below (also by Fuseli) we see many familiar objects – drapes, a bed, and a sleeping woman. The incubus, however, makes us realize immediately that this scene is not normal. Why is it sitting on the woman? Why is there a horse in the bedroom?! An ordinary and familiar setting has been transformed into the unexpected, creating the context for a nightmarish scene in which the every day has become something otherworldly and at odds with reality. There is an element of supernatural horror, but most of all there is a sense of the uncanny, or “unheimlich” – that which is familiar but somehow altered and strange.

We saw last time that Conan Doyle created a universe in his Sherlock Holmes stories which tallied with the Victorian ideal of moral and material domestic safety and comfort. It was from this platform that Jack the Ripper sprang to infamy, shaking the foundations of the Victorian world in a way that was graphically real and very much removed from fiction.

The Whitechapel Murders occurred between 1888 and 1891 (numbering eleven in total) in an area of London that was notoriously underprivileged and difficult to police. Whether or not all eleven murders were perpetrated by the same killer is contentious, but five of them, known as the ‘Canonical Five’, bear a strikingly similar modus operandi and are considered to be Jack’s work.

Press coverage of the crimes gripped the nation as the investigation unfolded and various theories were explored. Despite the best efforts of the Metropolitan Police Force (established in 1829), and particularly those of Inspector Frederick Abberline, certainty about the identity of the killer never seemed to be within their grasp. Furthermore, the cases of the Whitechapel Murders remain unsolved to this day.

Many of the press articles contained illustrations that tried to capture the grimness of the crimes. Above is an illustration from the Illustrated Police News which captures the horror of one of the murders very well. The light of the Police Constable’s torch contrasts with dubious looking dark patches on the ground that could be interpreted as shadow and dress fabric as easily as blood and gore. We already know that the Victorians were avid followers of shadowy mysteries, so it was no wonder that thousands of people followed reports of the Ripper cases almost as though they were installments in a serialized Gothic novel. The combination of the written word with accompanying illustrations was alone very powerful. Factor in the squalid living conditions to be found in the Whitechapel area at the time with the darkness of the streets at night and a thick London fog, and you have the perfect setting for the kinds of events that live in a nation’s psyche for a very long time.

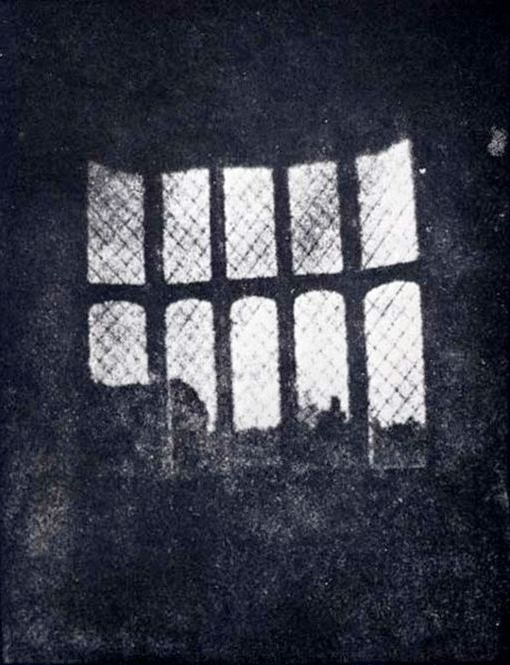

Photography was an up-and-coming technology in the Victorian Era. Pictured below is a photograph taken by Henry Fox Talbot in 1835 – a latticed window at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire – and the oldest known photographic negative. Fox Talbot was responsible for great advances in photographic methods, pioneering the salted paper and calotype processes, although he was by no means alone in this field as other advances were being made in Europe at the same time.

The Victorians took to photography with great enthusiasm, especially after it became publicly available. Photography was invaluable during, for example, the Ripper cases where it allowed the police to precisely record crime scenes, dead bodies, and potential suspects.

The possibilities of photography quickly spread beyond the law – quite literally in the case of pornographic images – and were used in a number of other ways by anyone who could lay their hands on a camera. The Victorians as we know were morbidly interested in death, but of course, loss and grief were as acutely felt in the 19th century as they are now. With the advent of new photographic technologies and increased access to cameras (or photographers in their studios), it became fashionable to take photographs of deceased loved ones as though they were still among the living. Despite its popularity, this type of photography was still expensive and remained a luxury available only to those who could afford it.

This sounds horrible until one considers that perhaps photography allowed people to come to terms with death, especially when it was personal, and softened the blow by making it appear that the departed was somehow still present. Queen Victoria herself kept a postmortem picture of Albert by her bedside as a memento mori.

Before Zoological Gardens there were menageries: private collections of exotic animals usually kept for the amusement and entertainment of royalty and their courts. Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror, established a menagerie at Woodstock in Oxfordshire which included lions and camels. Louis XIV had a menagerie built at Versailles which was stocked with a large variety of animals including several species of birds and a panther. Over time, however, it became apparent that species need to be studied and preserved in the name of science rather than kept solely for entertainment, and so began a shift from the menagerie to the Zoological Garden.

The Zoological Garden at Regent’s Park, also known as London Zoo, was first opened in 1828 to fellows of the Zoological Society of London. Later, in 1847, it was opened to the paying public in order to generate funding. London Zoo is the world’s oldest scientific zoo but there had been a strong interest in the natural world long before the Victorians. The painting below, while it may not be Victorian itself, resides in the Natural History Museum in London. Although it is from the 17th century it somehow doesn’t feel out of place in the 19th – concerns with exploring, documenting, and categorizing the natural world were still strong. Sightings of the Dodo had become rarer and rarer during the 17th century and it is likely that it was extinct by 1700. It’s fascinating to imagine what Victorian viewers would have made of this painting, especially if they were familiar with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland!

The Victoria and Albert Museum was founded in 1852 (although at that point it was known as the Museum of Manufactures) and is named after Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert. The original intention was to provide a learning resource following the Great Exhibition of 1851, in which design and manufacturing were showcased. Prince Albert felt that the building of an institution that would champion these areas and push them forwards was necessary.

Originally located at Marlborough House in Pall Mall, London, the museum quickly outgrew its site and thus was relocated to South Kensington. It was here in 1899 that the foundation stone of the V&A as we know it today was laid by Queen Victoria in her last public ceremony, and when the name of the museum was officially changed from The South Kensington Museum to The Victoria and Albert Museum. The final words of the Queen’s address from that day were:

I trust that it will remain for ages a monument of discerning liberality and a source of refinement and progress.

Queen Victoria on the Victoria and Albert Museum, 19.05.1899 speech, The London Gazette.

The museum’s vast collection includes over two million objects filling 145 different galleries. The V&A was also the first museum to collect photographs as art. The architecture of the Victoria and Albert Museum is art in its own right – even the tea room, known as the Gamble Room, and indeed many of the buildings that comprise the museum are absolutely beautiful!

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!