5 Things You Need to Know About Cupid

Cupid is the ancient Roman god of love and the counterpart to the Greek god Eros. It’s him who inspires us to fall in love, write love songs...

Valeria Kumekina 14 June 2024

In memory of the world-famous Italian art critic Germano Celant, who himself in 1967 invented the term Arte Povera, translated as “Poor Art”, we would like to present to you the most important and notable artists of this movement and glorify their philosophy of art expression not only by using and elevating simple materials but also posing a severe critique of the rising urbanization in the pre-industrial age.

From 1967 to 1972, in the major northern Italian cities such as Turin, Rome, Genoa, Venice, Bologna, and Milan, the so-called Arte Povera movement, or translated as “Poor” or “Plain Art”, began. As mentioned above, the term itself was coined by the Italian art critic and one of the Arte Povera’s major proponents Germano Celant. He also wrote a manifesto for the artistic movement, which was published in Flash Art in 1967. Between 1967 and 1968, Celant organized two exhibitions. One of them was called “Im Spazio” (The Space of Thoughts) and was held at the Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa. It is considered the official starting point of the Arte Povera movement.

One of the most important ideas of the Arte Povera movement is Ground Zero: It means a starting point – nothing. The idea of rejecting what came before. One of the participants in the Group Zero Art Movement and a person who influenced the Arte Povera movement among many was definitely Lucio Fontana, Argentinian by birth but working in Italy. He thought about the idea of existentialism, the idea of experiencing the work of art. The work of art does not tell you a story, but it does something to you while you are in front of it. Fontana used a monochrome canvas and made a very precise cut – it is actually very hard and not as simple as it may seem, the cut is perfect. The painting has nothing to say in terms of a narrative anymore. We can hear silence.

The ideas which Lucio Fontana brought forth during the 1950s involved the ideas of Space, Language, and Materiality. The same topics and ideas were presented by the Arte Povera artists, along with the rejection of conformity, of expensive objects, of durable materials as the permanence of ideas (as everything is in flux), breaking the idea of categories and boundaries not only in art. They didn’t care about the art market and they made fun of it, even though they didn’t escape it at all.

They also reacted to the Postwar period Italy which at the time was changing from day to day. In fact, Italy in those years experimented with the famous 1960s economic boom, a so-called “Miracolo Italiano” or Italian miracle. It was a period of high inflation. The lira was the most stable currency and therefore Italians experienced more freedom and independence as a result. After the war years they mostly felt hope which they transformed into experimentation and revolution in various fields, art included. However it didn’t last long, and the following disillusion and mistrust was the launching point for Arte Povera Artists.

The movement itself was born in an open controversy with traditional art. It rejected techniques and supports, and made use of the “poor materials” such as soil, wood, iron, rags, plastic, and industrial waste. Their aim was to evoke the original structures of the language of contemporary society after having corroded its habits and semantic conformity. Since the history of art is made of gold, silver, bronze, or marble, the use of earthy colors and elevating poor and simple materials is the reason why the art movement is connected to nature and interested in environmental issues, which started to raise many questions and preoccupations in the 1960s.

Arte Povera fits into the panorama of the artistic research of the time, due to the significant consonances it shows not only with respect to conceptual art, which in those years saw the rise of Joseph Beuys, but also with respect to experiences such as Pop Art, Minimal and Land Art. Key figures closely associated with the movement are Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Jannis Kounellis, Mario and Marisa Merz, Pino Pascali, Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Giulio Paolini, Gilberto Zorio, and others.

The goal of these artists was to overcome the traditional idea that the work of art occupies a supra-temporal and transcendent level of reality. Giovanni Anselmo is an Italian artist that has contributed to the Arte Povera movement through his thought-provoking sculptures. Works such as Sculpture that Eats (1968), reflect Anselmo’s interest in combining organic and inorganic materials to pose metaphysical questions for the viewer. For this reason, the provocation that derives from the work is important. It is formed by two stone blocks that crush a head of lettuce, a vegetable whose inevitable fate is to perish.

Jannis Kounellis was a Greek performance artist and sculptor. Originally emerging as a painter, he then shifted to making installations for which he is now widely celebrated. Kounellis created works that juxtaposed disparate materials, including stone, cotton, coal, bed frames, and doors. A prevalent theme in his practice was the incorporation of real-life — simulated or otherwise — into spaces of art. This phenomenon can be seen in works where he has installed live birds in cages alongside paintings, sculptures accompanied by the playing of a Bach score, and his reoccurring installations wherein twelve live horses are displayed in galleries or other art spaces.

The use of living objects is frequent, as Kounellis fixed a real parrot onto a painted canvas, demonstrating the fact that nature has more colors than any pictorial work. Or in Attico, where he put twelve horses in an “attico” or room. The horse as a noble animal had always been associated in the history of art with equestrian power. The horses of Kounellis could also be a direct influence for Maurizio Cattelan‘s stuffed horses such as Novecento (1997) or Kaputt (2013).

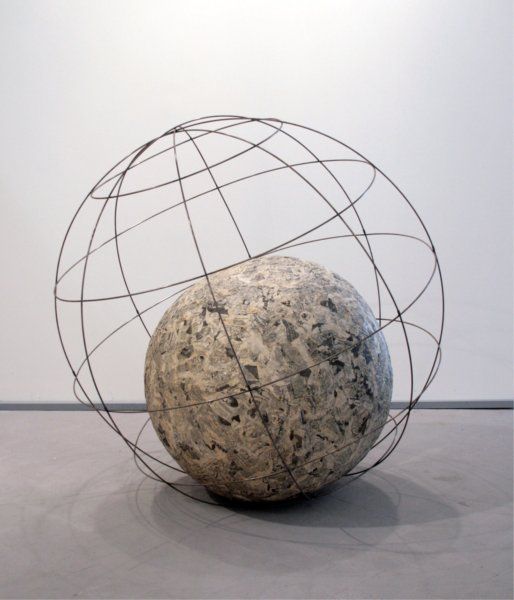

One of the most iconic artworks of the Arte Povera movement is the Venus surrounded by rags, created by the Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto. Pistoletto created a whole “Stracci” series, including sculptures made of rags, or his famous Newspaper Spheres executed between 1965 and 1968. They came to symbolize the overall Arte Povera movement for their use of a humble material. It is a regeneration.

Pistoletto is perhaps most famous for his “Mirror Paintings”, commencing in the early 1960s, which incorporate a reflective background. The very act of looking at one puts the viewer in the picture, or, as the Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli said: “Pistoletto anticipated the selfie.” If you want to learn more about Pistoletto’s oeuvre click here.

Most of the artists in the group show an explicit interest in the materials used while others – notably Alighiero Boetti and Giulio Paolini – had a more conceptual bent from the beginning. Another criticism carried out by the Arte Povera artists was that against the conception of the uniqueness and unrepeatability of the work of art. Mimesis, by Giulio Paolini, consists of two identical plaster casts representing a sculpture of the classical age, placed facing each other for the purpose of feigning a conversation.

Between 1967 and 1972, the critic Germano Celant invited Paolini to take part in Arte Povera exhibitions which resulted in his name being associated with the movement. In fact, Paolini’s position was clearly distinct from the vital climate and “existential phenomenology” that distinguished the propositions of Celant’s artists. He repeatedly declared an intimate belonging to the history of art, identifying programmatically with the lineage of all the artists who had preceded him.

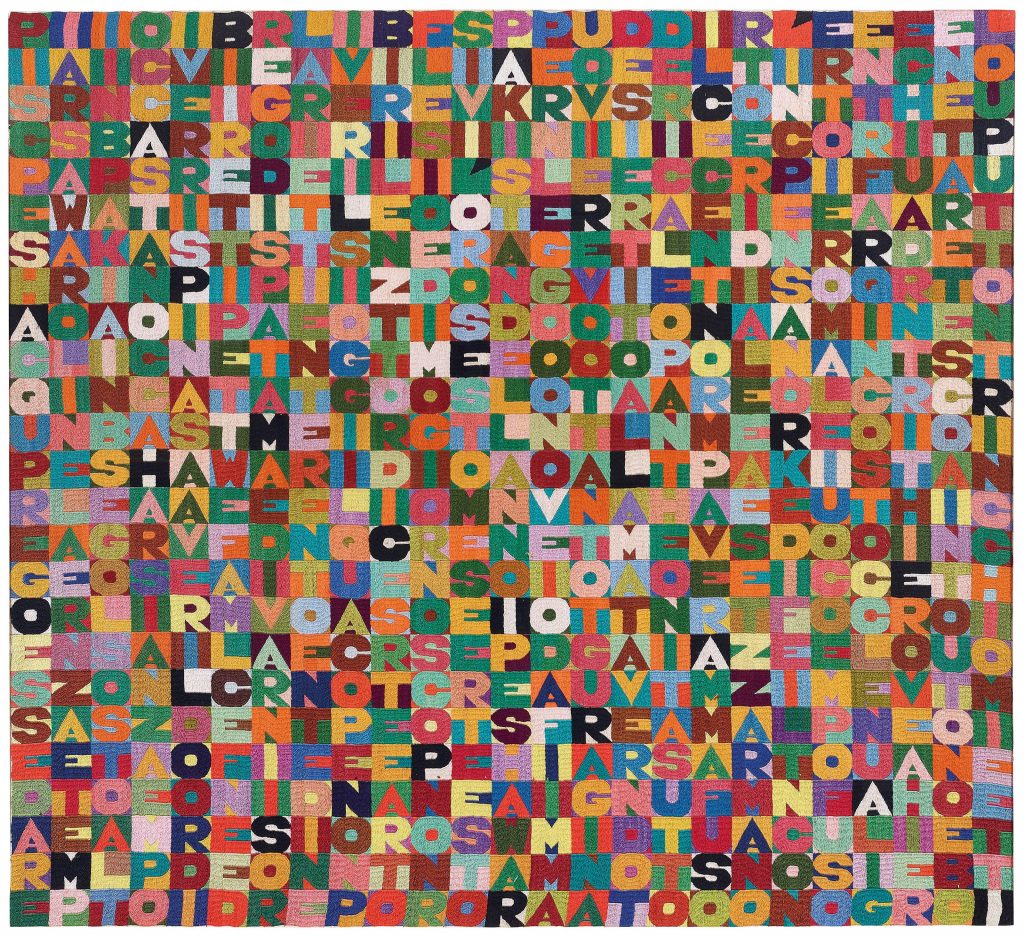

In Alighiero Boetti‘s tapestry, we can see some influence of the Pop Art movement because of the pop of colors he uses in his works. He often designed textiles to be embroidered in artisan workshops, like the one we can see above. From 1987 until his death, Boetti was completely absorbed in the creation of his largest and most complex tapestry, Tutto, which was created to represent the cultural diversity of the world.

Boetti used a wide variety of materials for his work too — including ballpoint pens and postage stamps — to make a series of maps and graphical charts of the world. Boetti died on February 24, 1994, and his large Map of the World (1989) is on permanent display as an important feature of the collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In addition to his works, in 1966 he created his Lampada Annuale, a lamp which every year illuminates for eleven seconds. Well, it seems to me quite difficult to be in the right place at the right moment. Good luck!

Italian artist Pier Paolo Calzolari is recognized for his sculptural installations and performances. Employing elemental materials like frost, plants, lead, and fire, the artist conveys concepts of existence and personal memory. In his works, we can see repeatedly recurring elements such as eggs or nutshells and through his many Still Lifes he focuses on the idea of time as a crystallization. One of his most interesting exhibitions was Ensemble, held in 2016.

Pino Pascali used everyday, natural, and unorthodox materials in his works, including cans, steel wool, hay, and dirt. His “fake sculptures” appear to be solid but are actually shaped canvases whose forms suggest animals, plants, and landscapes. One example is his 1966 work The Decapitation of Sculpture, which conjures a rhinoceros. He is best known for his Weapons series, re-creations of guns and cannons assembled from found materials and painted army green.

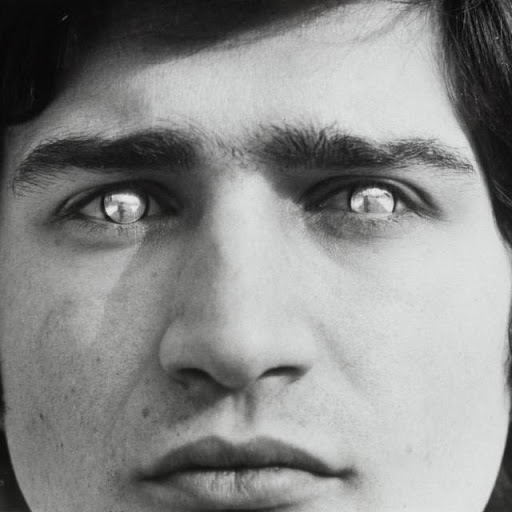

Since the late 1960s, Giuseppe Penone has challenged the boundaries between body and nature in his arresting performances, sculptures, installations, and works on paper. Penone first gained attention for his landmark performance, To Turn One’s Eyes Inside Out (1970). For it he wore a pair of mirrored contact lenses, which reflected and blinded him to the surrounding landscape. The lenses, though they deprived the artist of his own gaze, allowed him to objectively record images, literally reflecting his surroundings.

“I don’t want to change the material, I want to follow its lead.”

– Giuseppe Penone, interview at LA TIMES.

Penone relates to ecology and was always very critical of urbanization, to environmental changes causing pollution, et cetera. He wants to take us closer to nature. Thus he explores respiration, growth, and ageing — among other involuntary processes — to create an expansive body of work including sculptures, performances, works on paper, and photography. The work called Alpi Marittime – Continuerà a crescere tranne che in quel punto or translated in English as Maritime Alps – It Will Continue to Grow except at That Point, evokes the human and natural coexistence and sculpture’s intimate connections to the organic world.

In Spazio di Luce (2008) he made a cast of a tree, a double-sided cast actually, and on the outside we can see the fingerprints of the artist himself. It is not only a portrait of a tree but it’s a trace, a trace of a process between artist and tree becoming an object.

The artist also began to explore different ways of documenting his work, as well as his body’s interactions with sculpture. Essere Fiume (To be a River, 1981) marked an important turning point in Penone’s practice. The work represents the idea of mimesis in art, again something very primordial and essential to be placed as a protagonist of a work.

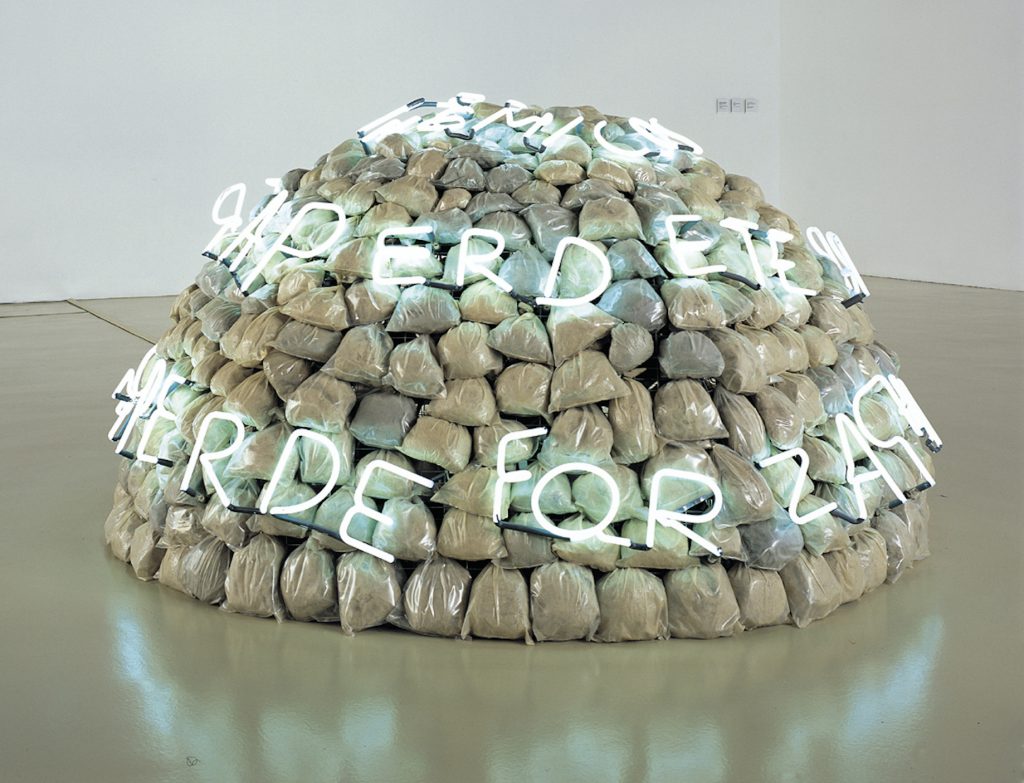

Attention to the lifestyles of many cultures different from those of the West is present in Mario Merz‘s works. His igloos, created with different materials (for example metal, glass, wood, etc.), highlight the adaptability of people to their particular environment and the idea of a shelter in a temporary dimension.

Mario Merz was one of the leading figures of the movement whose works used poor materials such as wood and beeswax. His piece, Lingotto, takes the name of an industrial district in Turin (his birthplace). It references the Fiat Factory, in which his father worked. A box made of beeswax, which the artist in his installation compares to the Fiat Factory, is also associated with wealth in the tradition of the Western culture and Classical art, as well as the financial wealth that came from the Fiat building where many people worked at that time.

Mertz got involved with mathematics, which became an ongoing interest for him. He mainly drew his attention to mathematical criterion of nature – Fibonacci sequence and the Golden ratio – as the proportionality of everything in nature. Next to his Zebra we can see the Fibonacci numbers lined in a sequence and highlighted with a neon lighting which was usually used in the advertising. With the use of neon lights, Merz expressed the uncertainty towards the 1960s felt by the whole nation at that time.

As the sole female member of the Arte Povera group, Marisa Merz, Mario’s wife, is an artist herself too. In 1926 she met and married Mario Merz and in 1965 she began producing her own works while sharing a house with her husband. Over the following decades, the artist combined objects and situations from her daily life with sculpture, painting, and installation.

Working with both traditional and non-traditional materials, the artist’s works often blur the categorization of domestic objects — blankets, bowls of salt, and boots — with art objects, such as sculpted heads and painted angels.

She was 90 years old when she first received a solo museum exhibition, Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space, staged at the Met Breuer in 2017.

“My artwork shows, with the language of sculpture, the essence of matter and tries to reveal with the work, the hidden life within.”

– Giuseppe Penone, My Modern Met.

In The Hidden Life Within, Penone carves out a young tree within an older tree to reveal its past, showing us what once grew inside so that it may now “live in the present.” Inspired by the quiet slowness of growth in the natural world, the artist asks us to take a moment to stop and think about the concept of time and how there’s a common vital force in all living things.

Arte Povera’s materials may have been plain and simple, but the ideas were rich. In their work, these artists registered dissent about the direction of society, putting in their art themes such as nationality, immigration, changing environment, rising urbanization, the loss of everything natural, and much more. They dealt with the value of time, as it manifests itself in nature, in everyday objects, in the human body, and in society. Behind their “ordinary” masterpieces, there is a deep philosophical and aesthetic base, a sense of intimacy, human scale, criticality, and ecological awareness and much more. They expressed simple things in a simple way. Simplicity is the first step of nature and the last of art. Or as the Italians say: “La semplicità è l’ornamento più grande dell’arte”.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!