Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

Queen Cleopatra is a popular subject today – as she was in the late 19th century. Alexandre Cabanel’s Cleopatra explores a single moment of her legendary life. It uses the extremely popular French Academy style of the 1880s to depict this 1st-century BCE figure. While the subject and style could be argued as staunchly traditional in the history of Western art, Cabanel adds a new vitality through his dramatic coloring and exotic scenery.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium.

France during the late 19th century was a period of prosperity, progress, and elegance. It was known as the Belle Époque (Beautiful Era), and it lasted from the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 to the outbreak of WWI in 1914. During the Belle Époque, the artistic world was dominated by government-sanctioned academies. In the United Kingdom, it was the Royal Academy of Arts, founded in 1768, and in France, it was the Academy of Painting and Sculpture, founded in 1648. The French Academy set the artistic standard of what was accepté (accepted) and what was refusé (rejected). Academicism was born.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889) was an Academic artist. He followed the Academic style through his graceful modeling, silky brushwork, and perfected forms. The overall manner was a polished illusion of a mythological or historical subject. Cabanel’s Cleopatra is a perfect example of the Academic style.

Cleopatra was created in 1887. It measures 287.6 cm wide by 162.6 cm high or 9 feet 5 inches wide by 5 feet 4 inches high. It has proportions similar to a modern widescreen of 16:9 that gives a contemporary feel to its formatting. Cleopatra and her attendant lounge on the right side of the scene, while five figures occupy the left side of the scene.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

The painting depicts the famous Cleopatra, specifically Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt. Her life is legendary as it combines all the elements of a great story: money, power, sex, and death. Many moments of her life, some real and some fictitious, have been depicted through different mediums since her death on 10 August 31 BCE. She has featured in memoirs, books, plays, operas, films, TV shows, music, and of course paintings. Cabanel’s Cleopatra is simply another example of a long tradition of historic retelling.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

The artistic world of 19th-century France was obsessed with Eastern Mediterranean cultures. Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Jean-Léon Gérôme represent the most ardent followers of Romanticism and Orientalism. They loved to explore distant cultures with lush interiors, nude women, and exotic animals. It was artistic xenophilia. Alexandre Cabanel dabbled in these two artistic movements with Cleopatra as his most notable example.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

Cleopatra explores the exotic and erotic. It depicts women who are not as heavily dressed as Western women of 1887. There is no hint of English Victorian, French Troisième République (Third Republic), or American Gilded Age modesty. Queen Cleopatra proudly displays her charms in luxurious decadent surroundings. Her breasts are full, firm, and uncovered. She wears vivid fabrics and sparkling jewels. Her cosmetics are heavy with deep red lips and kohl black eyes. For Western society of the 1880s, and for many people today, Queen Cleopatra represents the ultimate femme fatale (deadly woman).

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

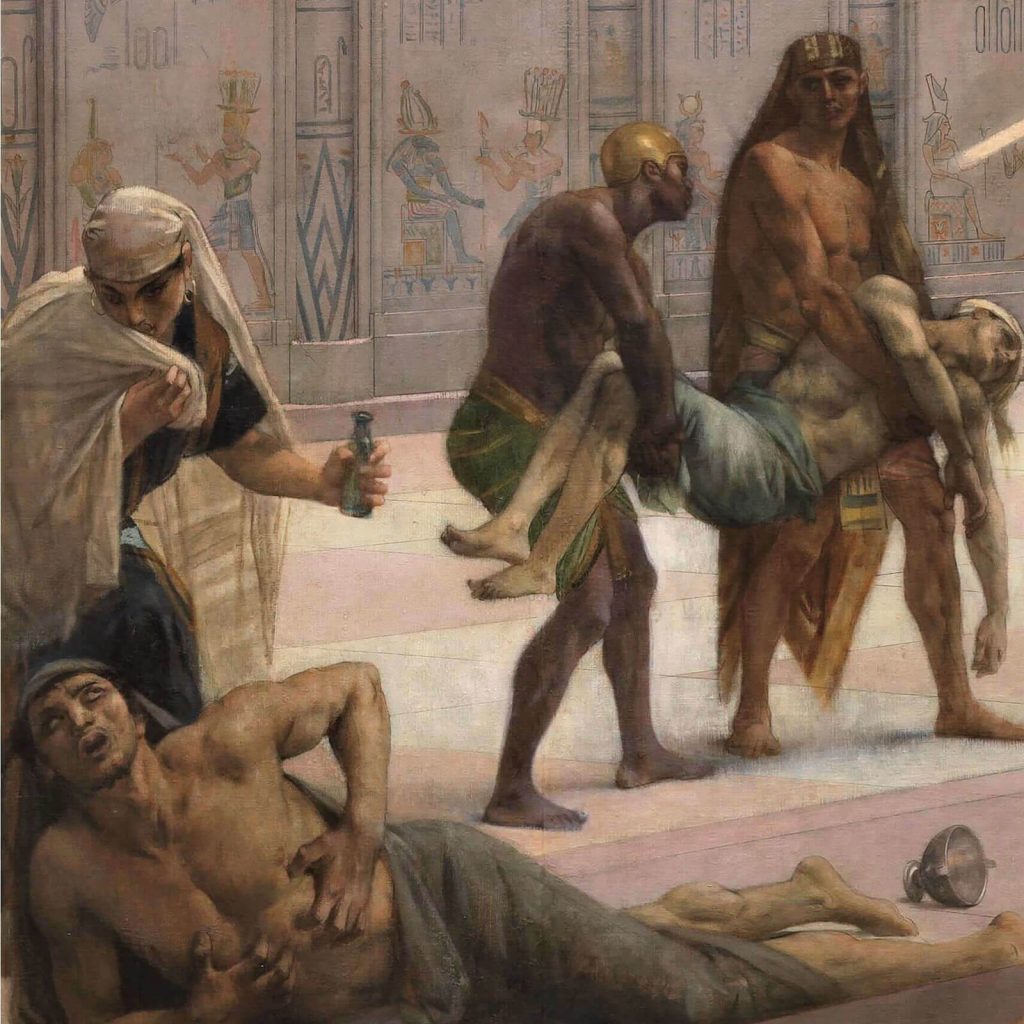

What are the figures doing on the left side of the painting? There seems to be one figure laying on the ground with someone crouching over, and another figure slack in the arms of two others. We are witnessing the dead and dying prisoners of Cleopatra. She is poisoning them to evaluate her poison’s symptoms and effectiveness. The man dying on the ground has an empty silver chalice laying discarded at his feet. The shrouded figure above him holds a green glass bottle. A small narrative is depicted here. The shrouded figure poured the poison into the silver chalice, the man drank the poison, he dropped the chalice, and now he has collapsed on the ground dying in pain. The three figures behind him show the final moments. The dead are carted away by two attendants.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

Why is Queen Cleopatra poisoning her prisoners? Many historians believe the tale of Cleopatra using an asp for suicide is unfounded. Cleopatra came from a long line of dynastic murderers who used various means, including poison, to eliminate their enemies. Many historians believe it is more likely that Cleopatra suicided on poison and, therefore, creating a painless but effective poison would have been important to her during her last days. Thus, Cleopatra may have used condemned prisoners as test subjects for her poisons. If the prisoners were doomed to die, they might as well help Cleopatra perfect the poison recipe for her own final use. These were extremely pragmatic times when life was cheap and dispensable.

Alexandre Cabanel, Cleopatra, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Detail.

Cleopatra is not a Realist painting, but it is painted in a realistic, yet polished, manner. It is not the radical avant-garde art of Impressionism, but not everything has to be radical to have artistic merit and value. There is a sense of beauty in traditionalism. Perhaps it is a sense of connection to the past, its feelings of comfort and familiarity? It is similar to the feelings evoked by traditions on public holidays and festivals. There is a routine feel-good element to it all.

Cleopatra is not a radical painting, but it is a radiant painting. It radiates color, confidence, and complexity. The Academic style of Cleopatra needs to be re-evaluated by modern society. Just because Impressionism succeeded Academicism, doesn’t mean Academicism was inferior. It was different, but not disappointing. Academic art needs allyship among the artistic community. It is a forgotten antique ring covered by layers of modern cheap necklaces in the jewelry box of art history. There is beauty and value in some traditions. Academic art is one of them.

“Birth of Venus.” Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

“Birth of Venus.” Collection. Musée d’Orsay. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

“Cleopatra.” Collection. Royal Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!