Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 10 June 2024

29 September 2021 min Read

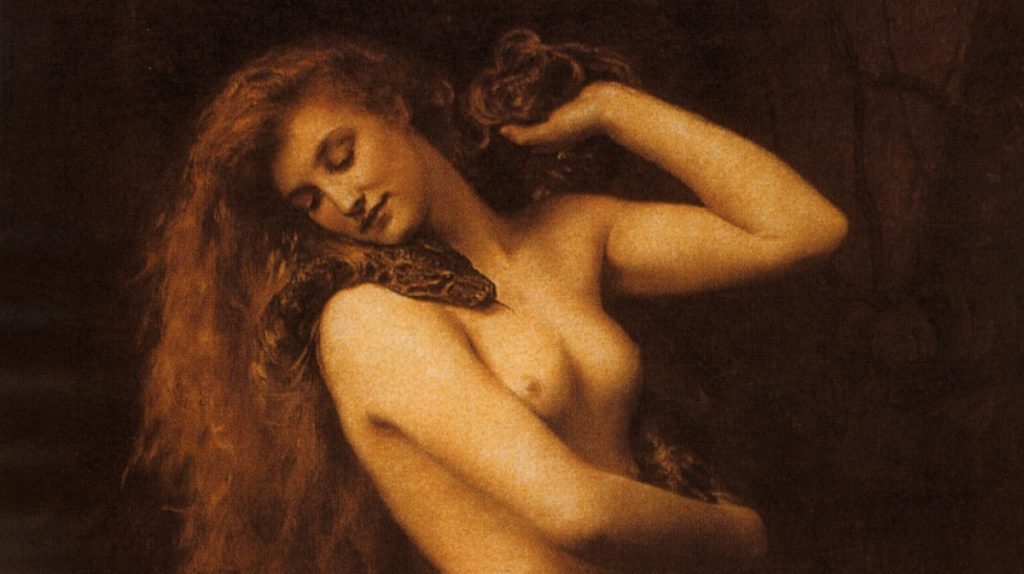

The apparent sweetness of this work by John Collier (1850–1934), a Pre-Raphaelite painter, is a wonderful testimony of the two sides of Lilith’s figure. Juggling between the images of sensuality, beauty, and that of a cold murderess, Collier is one of the artists that has transformed her image. From the Assyrio-Babylonian goddess, later known as the first woman in Jewish mythology, Lilith slowly turns into a powerful icon.

John Collier’s Lilith is a painting made in 1889, depicting the Kabbalistic demoness, known as Adam’s first wife. Born by the hand of the Creator, and shaped from impure clay, which influenced her demonic nature, she is punished and condemned to see her offspring die. Thirsty for revenge, she takes the form of the snake of temptation and incites Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. Abel is also a victim of Lilith’s perversity as she leads Caïn to commit fratricide.

From these sins, she obtains the image of a murderess and a temptress, harming in turn pregnant women and newborns. The danger that she inspires also results from the figure of succubus drawn up by the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), depicting her as a demoness with morbid and dangerous sexuality.

Way more ancient than the Jewish mythology, Lilith appears with all her vileness in Mesopotamia, in 4000 BCE. She appears in iconography and textual sources as a bird-shaped woman, endowed with wings allowing her to capture her victims easily. Hopefully, a great number of incantations offer a bit of security, as it aims to protect people from her perversity. Thus, a woman about to deliver a child must repeat “Pass quickly, o Lilith, do not devour my child, spare me” according to a Canaanite inscription from the 9th century BCE.

“O Beauty! Do you visit from the sky

Or the abyss? Infernal and divine,

Your gaze bestows both kindnesses and crimes,

So it is said you act on us like wine.”

Charles Baudelaire, Hymn to Beauty, 1861.

If Lilith is destined to inspire so much fear and disgust in the writings, she appears in a very different light in the hands of the artists of the 19th century. Perhaps guided by a certain affection of these subversive figures, poets and painters focus on showing Lilith as a seductress, whose beauty men cannot resist. Her cold infernal nature and irresistible charm are the characteristics that Charles Baudelaire, a 19th century French poet, lends to his lover, Jeanne Duval, in these verses “Horror is charming as your other gems, And Murder is a trinket dancing there.”

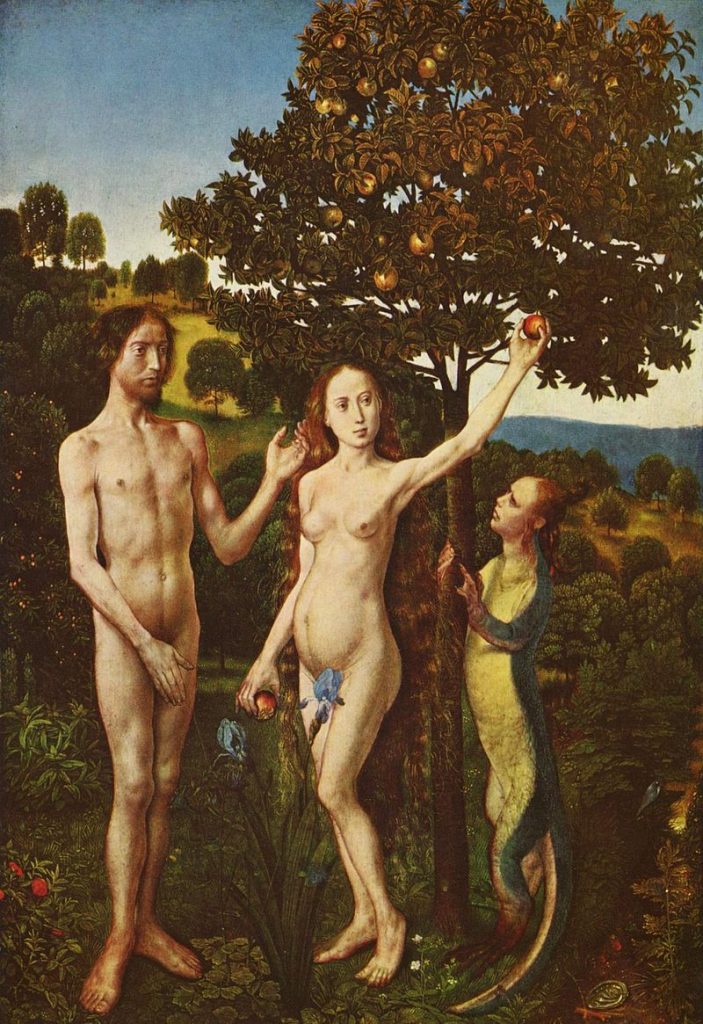

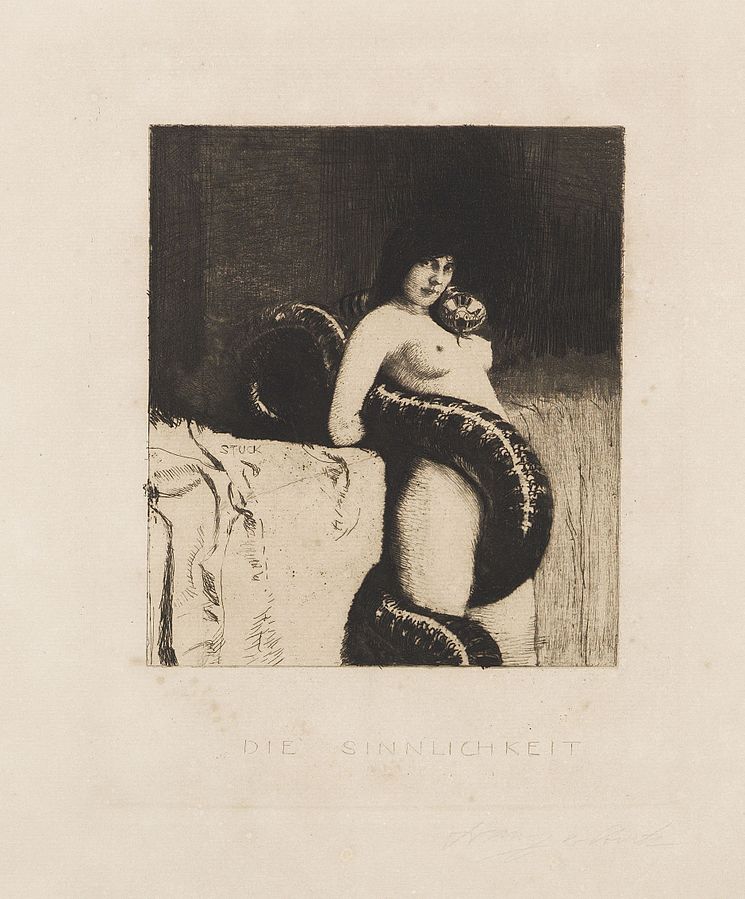

Detached from the notion of sin, artists strive to build a seductive image of a biblical transgression. In this way, they associate symbols such as bewitching women and snakes, the perfect symbol of evil. Sinful or sensual, the line becomes really thin, as shown in Franz von Stuck’s work. Two different titles, and yet only one subject remains – a woman embracing a snake.

In Collier’s work, Lilith appears in all her sensuality, in the scene where she incited the original sin. In the middle of the garden of Eden, symbolized by the heavy vegetation at the back, she stands naked as she leans her head lasciviously towards the snake twisted firmly around her. A snake that she does not fear, and whose form, according to Jewish mythology, she takes to pervert her victims. The inclination of her face reveals thick golden and wavy hair. Her curves are even more emphasized, barely hidden by the reptile.

The entire scene largely contributes to the voluptuousness released by Pre-Raphaelite work. Her luminous and milky skin detaches from the background and focuses our attention entirely on her fatal beauty. Collier, here, breaks somewhat with the coldness characterizing Lilith by depicting an alluring and almost serene image of her. The latter places himself as one of the first artists to depict Lilith this way – almost sweet, yet exalting a certain lust. Far from the religious depiction of the demoness, the artist then offers a nearly provocative image by depicting the perfect mix between calm and sensuality for such a sinful figure.

The contrasting colors of the painting, and its warm palette, further enhance the atmosphere that emerges from the work. This use of the colors, in Lilith as well as in Collier’s other portraits, earned him a certain recognition from his contemporaries. Seen as solemn, his work, however, offers an obvious mastery of tones and light.

Eventually, the figure of Lilith evolves gradually from the dangerous demoness depicted by the religious writings to a symbol of sensuality, but also of feminism. By her aspect of being equal to Adam, from whom she does not depend, the succubus becomes a feminist icon, a perfect opposition to Eve’s figure. Many powerful, sometimes feared, historical and mythological female figures are associated with snakes. These include Cleopatra and Medusa, whose association with snakes makes them desired, sensual, or monstrous.

Author’s bio:

Ophély Marques

Graduated in Archeaology and History of Art, I am currently studying Heritage and Museums at the Sorbonne. I am a fanatic of anything 18th century-related and love spending my life in museums. Patiently waiting to become a Curator, I share my love of heritage and art through my Instagram account.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!