Art and Life in Rembrandt’s Time at the Norton Museum of Art

Thomas Kaplan and his wife, Daphne Recanati Kaplan, have amassed the world’s largest private collection of 17th-century Dutch paintings. The...

Tom Anderson 5 February 2026

André Kertész is the patron saint of amateur photography. A man as full of passion for capturing life between glass and film as he is with crippling self-consciousness and jealousy at the success of his peers. He is one of the most prolific influencers of still photography that you may not have heard of. That is amended in Patricia Albers’ meaty biography, Everything is Photography: A Life of André Kertész, that turns the lens on the man who captured the torrent of the 20th century, bad angles and all.

André Kertész comes to us as a refreshingly complicated individual through Patricia Albers’ writing. I have never read a biography where the spotlighted subject feels so close to humanity. He is painfully stubborn, audaciously arrogant, charming when he needs to be, passionate, and lies when it suits him better than the truth. Then we read about the places he’s been in a heavily changing world, the photographers he has influenced, see the photographs he has taken, and are reminded why Henri Cartier-Bresson said, “Whatever we have done, Kertész did first”.

His personal history and his photography create a profound duality that plays out across his life: authenticity and artifice. The Jewish Hungarian boy, Kohn Andor, and the Parisian genius André Kertész. The devoted lover of one woman and the unfaithful rogue of three. The vibrant photographer who captured fantastic real life, and the old man retelling his life into something more fantastic. All the while, I am left feeling frustrated, mystified, and at times, all too understood.

Book cover of Patricia Albers, Everything is Photograph: A Life of André Kertész, 2026, Other Press, New York City, NY, USA. Publisher’s website.

One of the very first of relatively few photos is a portrait the artist took of himself and his camera’s shadow against a wall. The parallel was irresistible. I immediately clued in on the role Patricia Albers assumed as his shadow throughout the span of his often tumultuous life. The author records meticulous details from diaries and those who knew him and spins it back to us in an often amazing panorama of his life.

Albers spent 11 years on her subject, and like her thorough biography on Joan Mitchell in Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter, that mountain of information is expertly stopped, bathed, and dried into an often indulgently comfortable read. Something that I both loved and was surprised by is that her authorial voice is not totally out of view. Albers’ commitment to showing Kertész through a humanistic lens often results in her following up a bent truth Kertész told about himself, with the truth of what happened, or what most likely happened, when there is less evidence. Through this, Albers displays her own commitment to absolute authenticity.

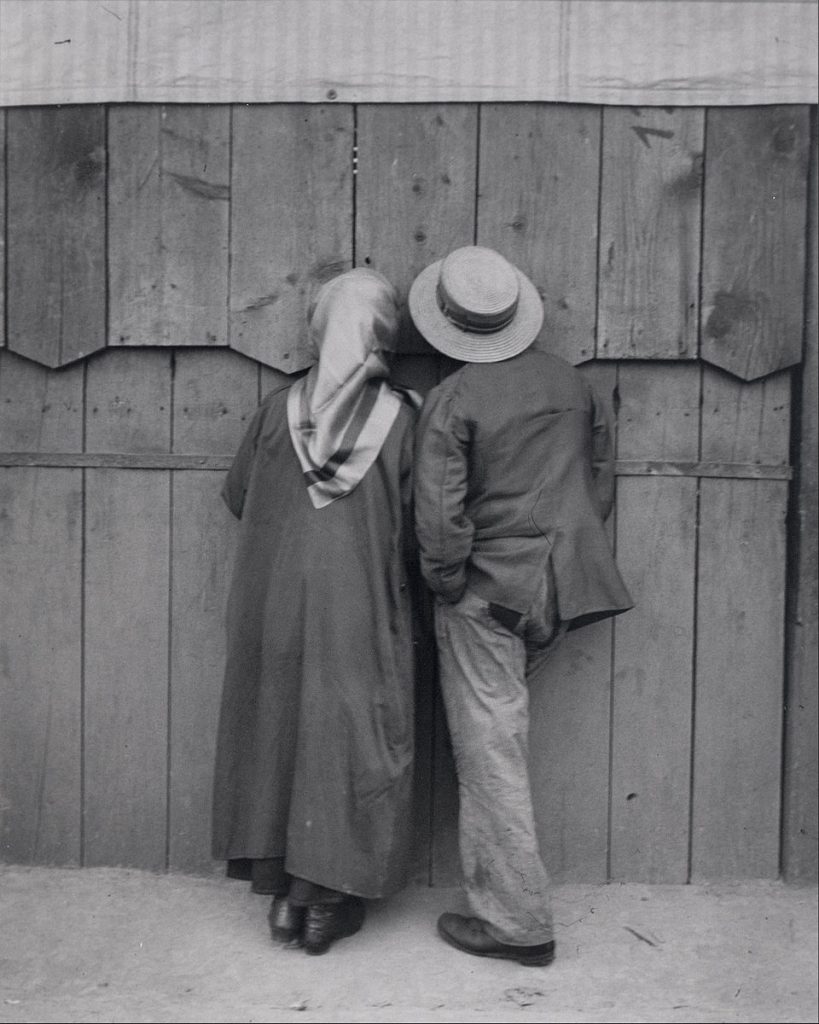

André Kertész, Circus, Budapest, 19 May 1920, 1920, Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, USA. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

What became apparent to me as I read through Albers’ work is that André Kertész’s Jewish identity is a central aspect of understanding him. We first meet him, as I mentioned before, as Kohn Andor (the last name is placed before the first in Hungarian tradition), which was then changed to Kertész, a more Hungarian one. This was the first time I saw what became a pattern of André changing piece by piece across the landscape of his life in a diaspora of identity. At times, he wanted and welcomed the changes—like his adoption of Paris as a surrogate home for him and the changing of his name from Andor to the Parisian, André. Other times, they were changes thrust upon him. During his service on the front lines of WWI, he saw tragic events like the slaying of unhoused German-speaking Jews by the Russians, which lingered with me as the reader.

He existed in a world where even if he didn’t fixate on his Jewish identity, the world did. He and his family would be snarled up in the bloody politics of the day, which led to events like losing homes and even death. André seems never to sit still, though, and even in the midst of such setbacks, he continued to capture moments that Albers describes with such simplistic beauty.

André Kertész, From the Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1929, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Albers makes a great comparison in the book between André and the Romani people when the artist is visiting them and taking photos. Like the nomadic people, Kertész is someone who yearns for the freedom to go wherever he wants, and photography is his portal to this life. Placed throughout the biography are detailed descriptions of André taking photographs, and I found myself looking forward to these small descriptive passages because they act like moments out of time, where the author pauses the world to focus on the quiet ritual of André’s photography.

These are the moments where André lives again, and there is a purity in reading about the artist in action. Photography takes him from the back country of Hungary to the streets of Paris, to the canyons among buildings in New York City, and even to Tokyo, where, later in his life, he is honored.

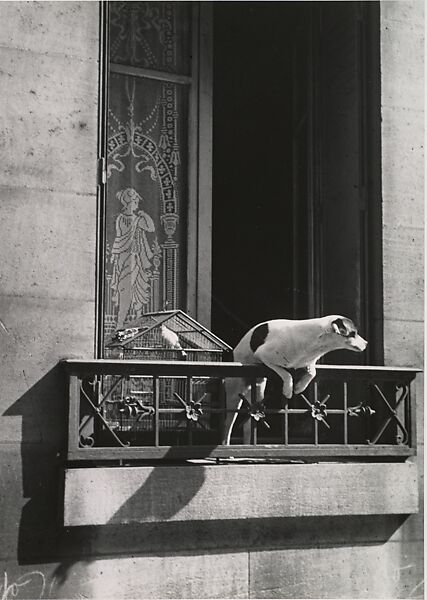

André Kertész, The Concierge’s Dog, Paris, 1929, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

What is remarkable to me is that I found myself ultimately more compelled by the times, places, and societal shifts than by the central subject of the book. This is due to Albers’ skillful weaving of contextual history to ground the personal experiences of André. One could argue he lived through the most important years of modern history. Like the staggering number of influential thinkers and artists he associated with and lived around (Le Corbusier, Atget, Man Ray, Cartier-Bresson, Ansel Adams, etc.), he is swallowed up by the 20th century and its tectonic movements.

This book is not simply a biography of the important photographer who set the benchmark for modern photography; it is a portrait of a world in lightning change, as it is swept over by savage wars, collapsing dynasties, overturned governments, genocides, and crippling depressions. It is also a portrait of the people who scramble to try to change with it. I was riveted by the world seen at macro-level perspective and poignantly paralleled to ours with haunting accuracy by Albers’ careful wording. This was the world that compelled André to point his lens at it while also alienating him within it.

André Kertész, Lost Cloud, 1937, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, USA.

In the biography, Albers highlights an interview between the author Jean Gallotti and Kertész on the subject of photography. She writes, “Gallotti presents André as a frustrating interview subject.” Then, when shown Kertész’s prints, Gallotti says, “he shows you a set of prints and, as soon as you’ve seen the first one, you regret that you have lost time in chatting.” This sums up perfectly what I experienced while reading this biography. André Kertész is an incredibly frustrating person. He constantly lied publicly about his life to make himself, as Albers says, “more hero, victim, or the lucky guy than he really was.” He was unfaithful to the women he loved and idolized, he was a ball of anxiety, and feared being a nobody, which led him to be incredibly self-centered and jealous of other peers’ success.

One such moment of jealousy led to an appalling decision to attempt to undercut and smother the attention an elderly fellow photographer was receiving for his photographs of Paris. Kertész softly copied this photographer’s most famous photograph with the intent to overshadow the elder. Plainly distasteful actions like this threaten to dominate my perspective on Kertész, but then, like Jean Gallotti, we read about his careful photographic routines that become rituals, and how he taught masters like Brassai the correct way to capture photographs at night. Kertész would literally starve for the art of photography because he believed it to be the art of the modernizing world. Like a true romantic, he could express his interior world exteriorly through his art. Most importantly, we read about his photos, like when he captured an image of a small white cloud lost and out of place next to the towering buildings of New York.

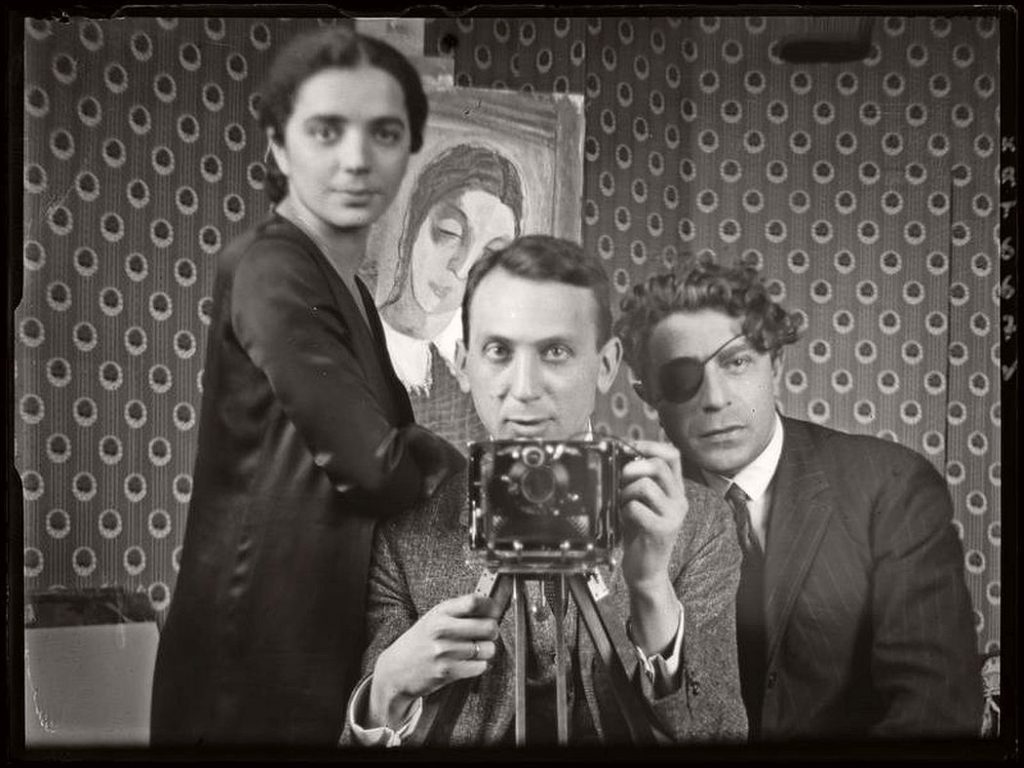

André Kertész, Self-Portrait with Friends, 1926. On this date in photography.

The well-worn adage says a picture is worth a thousand words. In the book, we read about photos so beautiful and full of delicate humanity, like that of a blind violinist being led by a child, and even though they are described beautifully by Albers’ well-established writing, I longed to see it and not simply read about it. For reasons unknown, readers are left only with 12 beautifully selected “diaristic” photos taken by Kertész to head the 12 chapters, and a grouping of contextual photos to show who’s who, nestled mid-book. The plethora of some of his most famous photos written about are absent, leaving me hungry with only the beautiful aroma of them to satiate my newfound appetite.

Luckily, Albers addresses this and adds footnotes to direct the reader to where we can see them, which I spent much time doing after reading. I would recommend all other readers do so as well, because the work of an artist is vital to understanding them.

André Kertész, Elizabeth and I in Cafe du Dome, Paris, 1931. Jackson Fine Art.

A question I wrote down upon reading the title: Everything is Photograph is “What does André Kertész mean by that?” I was pleased to see this is something Patricia Albers discusses towards the end of the book with eloquent insight; I will let the readers see for themselves what she has written. The answer I saw for myself was, to André Kertész, Everything is Photograph is equal to Everything is in Photograph.

In a world that changed so dramatically through technology, politics, and war and had taken so much from so many, it seemed clear that every photograph taken by Kertész was a piece of the world caught that he could have for himself. It was a meaningful or happy memory forever his, the camera being the window he never has to step away from, and a life never to be taken away again. André Kertész, I felt in some ways, is an unassuming subject for a biography, but now that the book is finished, I am back in the fast-moving world: politics, war, technology, societal upheaval, and cameras in everyone’s pockets.

Everything Is Photograph: A Life of André Kertész was published by Other Press in January 2026 and is available through the publisher’s website.

From The Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1929, J. Paul Getty Museum Online Collection.

The Lost Cloud New York, 1937, J. Paul Getty Museum Online Collection.

Patricia Albers, Everything Is Photograph A Life of André Kertész, 2026, Other Press, New York City, NY, USA.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!