Masterpiece Story: The Setting of the Sun by François Boucher

With sweet putti, handsome gods, beautiful nymphs, vibrant colors, and elaborate compositions, The Setting of the Sun is a testimony to François...

James W Singer 8 February 2026

The Cardsharps is an early masterpiece of Baroque art by Caravaggio that explores the revolutionary theme of crooked card playing. Let’s delve into all its details.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) is one of the pivotal figures in Western art history. He revolutionized and inspired a style of Baroque art that still receives admiration after more than four centuries. Caravaggio’s style is theatrical with bold lighting, dramatic plots, and psychological dialogue. His paintings are like frozen scenes in a play with solid backgrounds highlighting the actor figures.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA.

The Cardsharps, painted ca. 1596–1597, is an early masterpiece of Baroque art by Caravaggio. Caravaggio trained in Milan but relocated to Rome in 1595. The rich and powerful Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte acquired The Cardsharps and instantly recognized the genius of the artist. Therefore, the cardinal offered Caravaggio lodging in his palace, Palazzo Madama, a stipend, and access to Rome’s elite society full of future patrons and collectors. The Cardsharps could be argued as the painting that launched Caravaggio’s career.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

The Cardsharps is an oil on canvas measuring 94.2 x 130.9 cm (37 1/16 × 51 9/16 in.). It features a yellow-gray background typical of the Milan (Milanese) school of painting. Three figures dominate the composition as they surround a cloth-covered table. They hold cards and are engaged in a game. A backgammon set perches on the table’s left edge adding to the gaming and gambling environment. However, while gambling may be happening, it is happening within a deceitful and thieving environment. This is a crooked game where deception rules and innocence is lost.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

The idea of a crooked card game was an extremely new and innovative theme for Western painting. The Cardsharps is one of the first, if not the first, painting to depict such a scene. It inspired many contemporary artists such as George de la Tour to explore the underworld of slanted card playing. With every dishonest card game, there is always a loser. Therefore, who is the dupe?

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

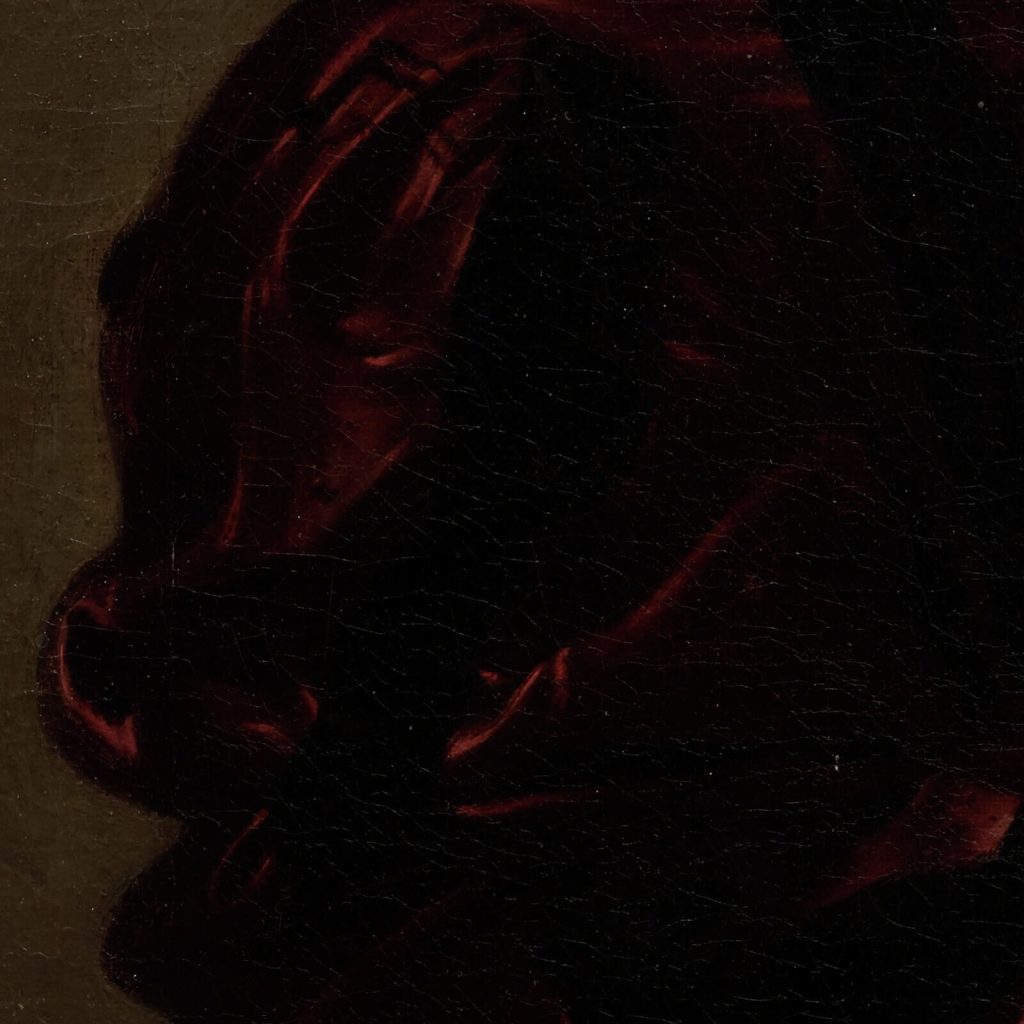

The left player is the dupe. He is a handsome youth with dewy light skin, pink lips, and firm dark eyebrows.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

He wears an extremely fashionable outfit of rich plum velvet and black embroidery. His collar and cuffs are edged in crisp white linen. Atop his head is a matching velvet plum-and-black hat adorned with black ostrich feathers. He oozes the persona of a young rich dandy. However, perhaps a little naive to play with such unscrupulous characters. While he glances down to his cards in hand, the other two figures are in the process of cheating him.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

The right player is the cheat.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

His immoral intentions are expressed through the two cards secretly concealed in the back pocket of his waist. There appears to be an eight of hearts alongside a six of clubs. The cheat’s right hand is pulling the six of clubs as it must be the better option to win the round.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

In fact, it is the only card of the two to play because the competitors are playing primero, a forerunner of modern poker. In primero, a standard deck is used but with all the 8, 9, and 10 cards removed. Therefore, in this game of bluffing and betting, playing a hidden eight of hearts would be impossible and a clear indication of cheating! The cheat must be wary of pulling the correct card if he wants to keep his deceitful advantage.

The cheat lures the dupe into a forged sense of security with false pretenses. He pretends to be a respectable young gentleman with his wispy mustache, silk doublet, feathered cap, and short sword at his waist. However, the quality and style of his attire reveal his duplicity as an imposter gentleman. The dupe reflects his true high social status through his finely coordinated clothing. The cheat has mismatched clothing that presents a sloppy attempt at refinement.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

The pale blue sleeves do not match the yellow striped doublet (waistcoat), and they are not properly sewn revealing the white undergarment at the shoulders. The cheat’s doublet is yellow with black stripes similar to a wasp’s appearance. Like the venomous insect, the cheat is ready to sting the dupe, however, not physically but morally and financially. His intentions are dirty like his fingernails. Finery cannot hide the true muck of his soul.

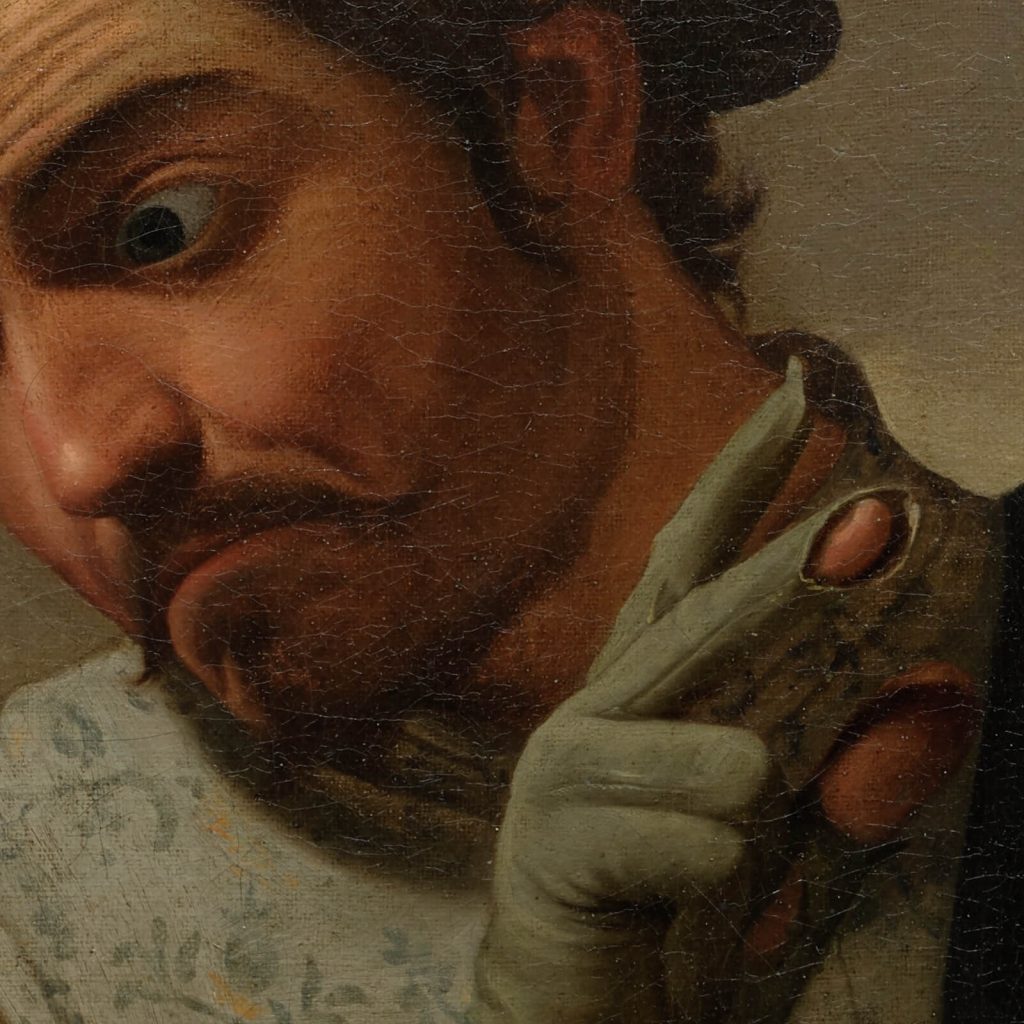

The central figure is the accomplice to the cheat. He is posing as a respectable spectator to the two-person game, but he is actually observing the dupe’s cards and then signaling to the cheat. Like the cheat, his mis-matched attire reveals his lack of gentlemanly wealth. His grey floral doublet appears faded and worn at the edges. Perhaps this is clothing acquired at a second-hand clothing market stall? Or perhaps it is stolen clothing? His shabby appearance continues with the holes at the fingertips of his gloves. However the holes are not pure shabbiness, they are intentional apertures to feel marked cards.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

The accomplice looks over the shoulder of the dupe and then raises two fingers to indicate the cheat. Perhaps the dupe is holding a two of something? Or perhaps the two fingers are a pre-arranged signal to pull the spare card? The hidden meaning is vague to the viewer, but its presence strongly indicates a hidden language of allied deceit.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

Why is there a backgammon set to the left of the composition? Why is it partially jutting over the edge of the table? It is possible that the backgammon was played prior to the primero. Alternatively, it could be a ready-made device to create a much-needed distraction. The cheat could easily knock it over with his left hand which currently rests on the table. With the loud clatter and visual chaos, the cheat could easily slip or exchange the six of clubs from his right hand into his left hand and presumably win the game. The backgammon’s precarious position adds a visual tension to the already tense game.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

Caravaggio’s figures were either praised or condemned for their earthy realness. Caravaggio was even denounced as the “Anti-Christ of Painting” by one of his harshest critics. He liked to use real Roman street people as models to give a sense of immediacy to the viewer.

Caravaggio was not an idealist seeking perfection as did most artists under the earlier Renaissance period. He rejected idealistic religious scenes and flattering portraits. His paintings have dirty feet, unclean nails, large warts, and deep wrinkles. He sought rough and daily representations of life that ushered in the early Baroque period. The Cardsharps exemplifies this artistic philosophy and is one of Caravaggio’s best preserved paintings. It is an early masterpiece of Caravaggio and the larger world of Baroque art.

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, ca. 1596–1597, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, USA. Detail.

“The Cardsharps.” Kimbell Art Museum Online Collection. Retrieved December 20, 2025.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA, USA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!