Beyond Surrealism: Establishing a Dialogue Throughout History

More than a historical avant-garde, Surrealism continues to function as a living language, one capable of addressing uncertainty, desire, and...

Carlotta Mazzoli 5 January 2026

“Shadows are rare here. There’s sunshine everywhere except on you”—so opens Christopher C. Gorham’s new book, Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi Occupied France. It accounts the little-known story of Henri Matisse and his family’s involvement in the French resistance in World War II, as well as the influence it had on the creation of his iconic cut-outs. It’s a sensitive and illuminating read starting in Nice in 1938, taking us through World War II up until Matisse’s death in 1954.

Things turn dark very quickly, and we are steeped in Henri Matisse‘s wartime life. Gorham fluidly weaves the details of the war, complex family relationships, Matisse’s deteriorating health and physical condition, and ties them all together by his art, his need to create, and his need to stand for his country.

The book is dramatic and intense, making the time period, the struggles, and Matisse’s artistic battles palpable. Despite being a long-time admirer of Matisse’s work, I knew very little of his life, but the story leads the reader along and provides what is needed to follow along easily.

Cover of Christopher C. Gorham, Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi-Occupied France, Citadel Press, 2025. Penguin Random House.

Matisse’s entire life had been marred by war. He was born right before the Franco-Prussian War, then lived through World War I, and World War II. Living in Nice in 1941 under Nazi occupation, Matisse was 72, frail, and in failing health. He was separated from his wife of over 40 years and dealing with tempestuous relationships with his family. He spent most of the war with his model, studio assistant, and caretaker, Lydia Delectroskaya. During this time, he underwent a bowel surgery that he almost didn’t survive, but he was determined to carry on and finish his work.

Lydia Delectorskaya in her studio, 1935. Le Point.

The book delves into Matisse’s relationship with his art, showing it was a source of frustration as he sought new ways to push his abstraction and accommodate his physical limitations, and that it was also his main driving force in life, always pulling him through any darkness. Art was his torment and savior.

Unlike many other prominent figures, Matisse stayed in France during Nazi occupation. He felt it important not to desert or abandon the country. Gorham recounts Matisse’s patriotic viewpoints through the artist’s letters with friends such as Picasso, poet Louis Aragon, and painter Pierre Bonnard. Several members of the Matisse family were part of the war efforts and French Resistance, and there is great detail on the capture, torture, and brutality his family survived.

Matisse Family: Henri, Amélie, Pierre, Marguerite, Jean, 1911. Musée Musings.

I am affected by the same things that affect the community…Many painters have told me that the war, for instance, has in no way affected their painting. It is impossible that an artist should not feel the after-effects of the war. That makes him take things more profoundly.

Christopher C. Gorham, Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi-Occupied France, Citadel Press, 2025.

The story highlights Matisse’s struggles and infirmity after his bowel surgery was one of the main driving factors in the development of his signature cut-outs. Often unable to stand or move to paint and sculpt as he did before, he was frequently confined to a wheelchair or lying down. By necessity, he discovered that cutting shapes and figures from paper was much more manageable. This new style was also important to him as he was looking for ways to stay relevant and experiment in his abstraction.

Matisse at the Hôtel Régina, c. 1952, Nice, France. Lydia Delectorskaya © 2014 Succession H. Matisse. Museum of Modern Art.

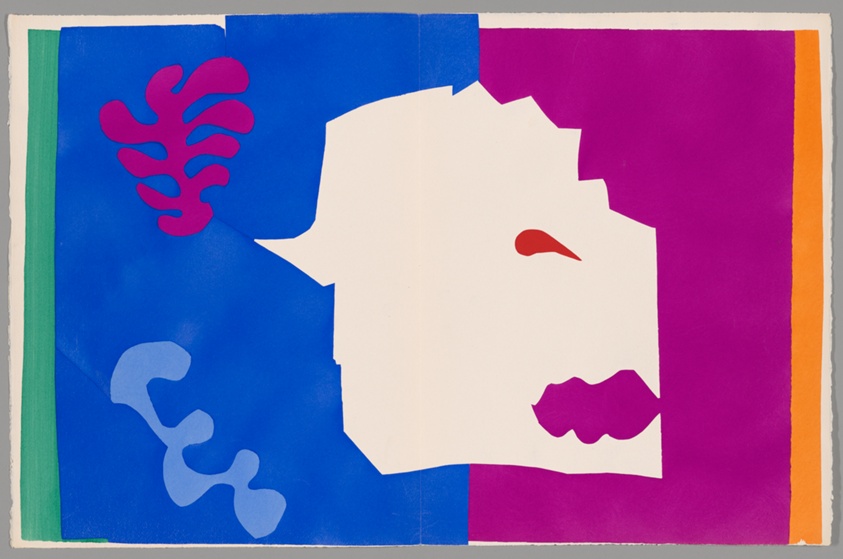

Matisse’s most famous collection of cut-outs known as Jazz was originally titled The Circus. Many pieces in Jazz maintain the circus theme: Fall of Icarus, The Wolf, Cowboy, and Ring Master, and these works were very much influenced by Matisse’s experience of the war. Growing up in 19th-century France, the circus was a popular past-time for families. The colors, lights, variety of performances were all part of a collective nostalgia of fun, enjoyment, and excitement. But during World War II, just like Matisse was categorized as a Degenerate Artist by the Nazis, so was the circus. This was Matisse’s motive to pursue these themes.

There is a powerful passage quoted from art historian Dr. Rodney Swan that this “was also a counter to Aryan ideals of physical perfection and racial and ethnic purity. What could be more different than the itinerant outcasts who lived and worked under the circus tent?..The marginalized that Hitler condemned…Circus also means the integration of different ethnicities, races and abilities.”

Jazz music also falls into that category, and Matisse plays with its themes of improvisation, freeness, and liberation—a perfect complement for his vibrant cut-outs. Without knowing the background of the works, the vibrancy and colors of the cut-outs seem lively, drawing the viewer along the abstract curves and lines, but the narrative is dealing with darkness, violence, and even danger.

Henri Matisse, The Fall of Icarus from Jazz, original lithograph after the paper cut-out and gouache, 1943, Eames Fine Art, London, UK.

Arguably one of his most famous pieces, The Fall of Icarus, depicts Icarus with a red dot through his heart, falling against a bright blue background dotted with bursts of yellow, which Matisse described as bombs. Icarus’ body is so limp almost corpse-like, and is suggested to represent Matisse’s deteriorating physical strength.

There is also focus on The Wolf, with its menacing teeth and blood-red eye—evoking the terror and surveillance instigated by the Gestapo occupying French cities.

Henri Matisse, The Wolf from Jazz, color pochoir with gouache on ivory woven paper, 1947, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

“I live only for the light and in search of its subtleties, I have been to the ends of the earth”—one of the many beautiful quotes from Matisse in the book, and one that feels applicable to all of us who love and study art. Much like Gorham does with his writing, highlighting the darks and lights of Matisse’s world. Gorham’s interest and care for the subject matter and time period are evident, and his personal connection to Nice adds a layer of exploration and reverence. The topics and stories dealt with in the book are heavy, but there is also such a deep respect for Matisse’s work, his creative process, and the resilience of him and his family members that it makes for an uplifting and inspiring read.

Matisse at War. Art and Resistance in Nazi Occupied France by Christopher C. Gorham was released on September 30th, 2025 by Citadel Press.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!