The Frank Stella You Thought You Knew

You may know Frank Stella from the brightly colored, shaped canvas paintings in his Protractor series from the late 1960s to early 1970s. However,...

Marva Becker 11 July 2024

The Venice Biennale is one of the most prestigious art events globally. Here are our top 10 national pavilions to visit for the 2024 edition.

Officially opened to the public on April 20th, the 60th International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia has already sparked debates and aroused questions. Curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Venice Biennale 2024 is titled Stranieri Ovunque (Foreigners Everywhere) and sees the participation of over 300 artists from 80 countries.

As usual, alongside the main exhibition, split between the Arsenale and the Central Pavilion at Giardini, the Venice Biennale 2024 hosts a number of national pavilions. Out of the 87 pavilions spread around the city, some countries saw their first participation this year, such as Ethiopia, while others were well-established presences. As it often occurs, the national pavilions offer the best insights into the Biennale’s theme and some of the most interesting projects presented for each edition. This is particularly evident this year, where the main exhibition was often referred to as lacking a bit of the spark and innovation seen in previous editions. On the contrary, many of the national pavilions presented compelling projects and a more in-depth analysis of the “foreigners” theme Pedrosa gave to this year’s Biennale.

It is not always easy, though, to navigate through all the different locations and pavilions, and given the high number of different proposals, we decided to offer our expert guidance with the 10 best pavilions for Venice Biennale 2024. With a selection of pavilions from inside Giardini and Arsenale, as well as a number of pavilions scattered around Venice, this list will help you explore this year’s best national participations and understand the true essence of Stranieri Ovunque.

Yuko Mohri, Compose, 2024. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia/Frieze Magazine.

Starting from Giardini, the first national pavilion worth visiting, titled Compose, is Japan. Featuring installations by Yuko Mohri, the pavilion is filled with lights, sounds, and smells that leave the visitors both amused and perplexed. Inspired by Tokyo subway station workers’ efforts to stop water leaks, the first work, Moré Moré (Leaky), artificially creates leaks and then attempts to fix them, reflecting on the urgent issues of flooding and climate change. In a city like Venice, which often suffers from such events, the work is a reminder of how fragile our world is.

Meanwhile, the work Decomposition generates sounds and light by inserting electrodes into fruits and converting their moisture into electric signals. Over time, the changes in the state of the fruits will modulate the pitch of the drone and the intensity of the light, and they will start emitting a sweet smell of decay, dissolving, or withering. With her pavilion, Mohri urges people to work together in a world facing multiple global crises, which paradoxically, just like it happens for the subway workers, inspires the most resourceful measures.

Archie Moore, kith and kin, 2o24. Venice Biennale/Andrea Rossetti/ABC News.

Remaining in Giardini, Australia’s national pavilion is another one worth visiting, not only because it won this year’s Golden Lion for the best national participation. The grandiose architecture hosts the work of Archie Moore, kith and kin, curated by Ellie Buttrose. The pavilion offers a close-up look at First Nations peoples of Australia, some of the oldest continuous living cultures on Earth, but also one of the most incarcerated populations.

Through a chalk-on blackboard mural, featuring Kamilaroi and Bigambul words, and holes that signal colonial invasions, massacres, diseases, and displacement, the artist traces relations that date back 65,000+ years, including the common ancestors of all humans. At the center of the pavilion, on the contrary, Moore poses a memorial to First Nations deaths in state custody attended by piles of coroners’ reports, to demonstrate how colonial laws and government policies have long been imposed upon First Nations peoples, using his family history to make systemic issues uncomfortably tangible to the audience.

Julien Creuzet, Attila cataract your source at the feet of the green peaks will end up in the great sea blue abyss we drowned in the tidal tears of the moon, 2024. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia/Frieze Magazine.

Steps away from the Australian pavilion, France offers a more playful take on Venice Biennale 2024 theme. Featuring works by Julien Creuzet, and curated by Céline Kopp and Cindy Sissokho, the French pavilion is a kaleidoscope of colors and fuzzy shapes. Inspired by Martinique stories, the pavilion is configured like a massive installation, presenting videos, sounds, and sculptures, that recall the sight of the matoutou falaise, a phenomenon that appears in dense forests and requires a deep connection to the environment.

The pavilion is an immersion in forms and sounds, volumes and lines, colorful figures, and unspoken languages. Taking inspiration from tarantulas, which are endemic to Martinique, Creuzet created an ecosystem that transports us to a new territory. As foreigners in this environment, we are taken to new shores, learning new skills, and awakening our senses.

Open Group, Repeat after Me II, 2024. DTF Magazine.

The last pavilion in Giardini to visit is that of Poland. Featuring the work of the Open Group, a collective composed of Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach, and Anton Varga, Repeat after Me II is a collective portrait of witnesses of the war in Ukraine. The protagonists of the two films, shot in 2022 and 2024, are civilian war refugees who speak of the war as recalled through the sounds of firearms and then invite the audience to repeat the same sentences after them. The artists use a karaoke format, but there are no catchy tunes to accompany these songs, just shots, missiles, howling, and explosions, in an effort to teach these sounds and potentially save the lives of those listening.

Repetitive and obsessive, the pavilion envelops the visitors in a dark atmosphere and offers several inputs for reflection, from the growing power of nationalist parties to the disruption, both physical and mental, that war brings upon populations.

Manal AlDowayan, Shifting Sands: A Battle Song, 2024. Photo by venicedocumentationproject/National Pavilion of Saudi Arabia.

Moving on to Arsenale, another great pavilion to check is the Saudi Arabia one. Curated by Jessica Cerasi and Maya El Khalil, the pavilion features the work of Saudi artist Manal AlDowayan, Shifting Sands: A Battle Song. The work is inspired by the evolving role of women in Saudi Arabia’s public sphere and their ongoing journey to assert their place and reshape the narratives that have historically defined them.

At first glance, the pavilion presents large-scale sculptural elements that remind of the forms of the “desert rose”, a crystal commonly found in Saudi Arabia’s desert sands. The surface of these sculptures is silkscreened with texts written about Saudi women, a cacophony of media opinions that have had a profound impact on their perception and obscured their own self-representation. But at the center of the installation, a shift occurs. Through a series of participatory workshops, AlDowayan gave Saudi women a platform to express and talk about themselves, without the prejudices and narratives imposed by third-party voices.

Roberto Huarcaya, Huellas cósmicas (Cosmic Traces), 2024. Arte Aldía.

When visitors step inside the Peruvian pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024, they lose almost all their spatial references and are forced to focus on the two large-scale pieces presented in this dark setting. Curated by Alejandro León Cannock, the pavilion features the work of photographer Roberto Huarcaya, who has roamed Peru for over a decade, creating monumental photograms that mix photography, installation, and land art. Questioning our way of representing our environment, Huarcaya uses a photosensitive surface to register traces of light, dust, water, plants, and insects.

The resulting installation, Huellas cósmicas (Cosmic Traces), places the spectators in an undetermined experiential space and time, challenging their attention habits. It operates as an immersive, transitive ritual haven to spark awareness, stoke the imagination, and encourage meditation, inviting spectators to reassess their environment taking a sensitive, non-instrumental stance.

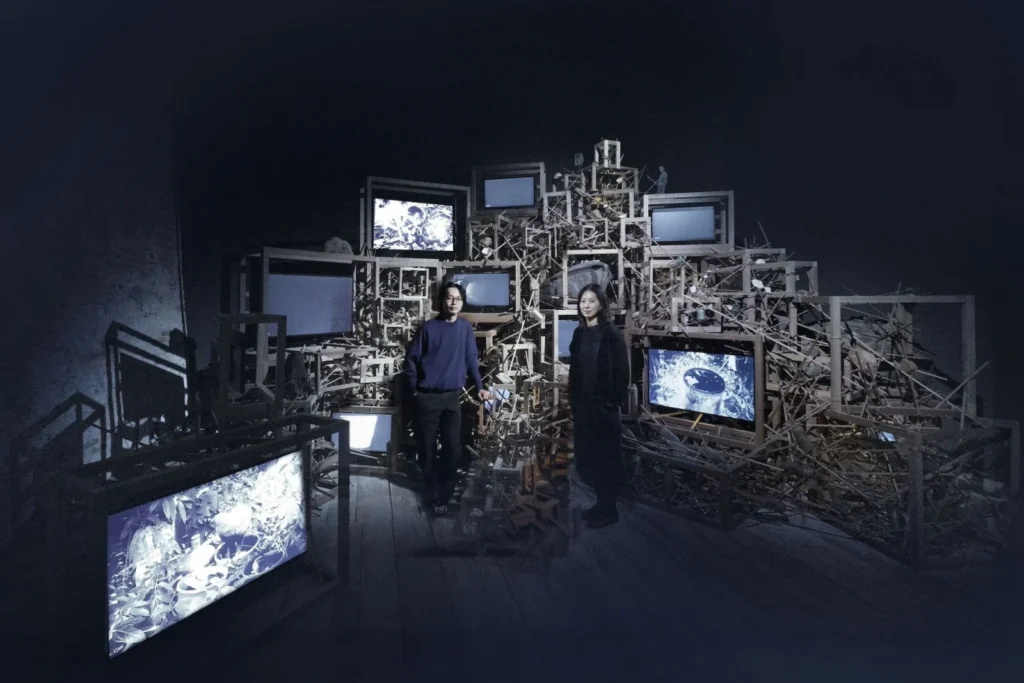

Robert Zhao Renhui and Haeju Kim with Trash Stratum (2024), as part of Seeing Forest, 2024. Photo by Robert Zhao Renhui/Tatler.

The last pavilion worth checking at the Arsenale is Singapore’s, titled Seeing Forest. Curated by Haeju Kim and featuring the work of Robert Zhao Renhui, the pavilion offers an evocative exploration of secondary forests, areas where nature has regrown over land previously disturbed by human development, becoming the threshold between undisturbed primary forests and developed urban environments.

Through the study of Singapore’s secondary forests and their inhabitants, the pavilion reflects upon the histories of settlement, colonization, migration, and mutual co-existence amongst species. At the same time, it reveals how these transitional spaces can offer points of intersection for history, sustainability, and discovery, and reflects on the importance of the edges of a city, as the place of exchange and a modern frontier between worlds.

A view of Nigerian Pavilion, 2024. Photo by Marco Cappelletti/Widewalls.

For the last three pavilions, we move outside of the Arsenale and Giardini and visit those located around the city of Venice. The first one is the acclaimed Nigeria pavilion, located in Palazzo Canal. Curated by Aindrea Emelife, Nigeria Imaginary explores the role of both great moments in Nigeria’s history and the Nigeria of the mind, a country that could be and is yet to be.

Presenting different perspectives and constructed ideas, memories, and nostalgias regarding Nigeria, the pavilion leverages an intergenerational and diasporic lens to imagine Nigeria for the future. The pavilion features the work of Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Ndidi Dike, Onyeka Igwe, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Abraham Oghobase, Precious Okoyomon, Yinka Shonibare CBE RA, Fatimah Tuggar, that explore themes of colonialism, Nigerian modernism, and utopia.

Moffat Takadiwa, Dudu Muduri, 2024 at the Zimbabwe pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2024. Photo by Candice Allison, Courtesy of the Zimbabwe Pavilion and National Gallery of Zimbabwe.

Curated by Fadzai Veronica Muchemwa, Undone is hosted in Santa Maria della Pietà and features works by Gillian Rosselli, Kombo Chapfika, Moffat Takadiwa, Sekai Machache, Troy Makaza, and Victor Nyakauru. The pavilion centers around the concept of kududunuka, an exploration of ideas of the unraveling of the world.

The exhibition is a way to rethink and reimagine a potential future. It hearkens to being unfaithful to imposed ideas of time, geography, space, identity, nationhood, humanity, migration, and the suppleness of the ever-changing landscape of what we call home. Through the work of the presented artists, the pavilion helps the viewers discover our peculiar position, right on the cusp of our time, just minutes away from massive changes that are long due. This exhibition, therefore, provides a space for reflection, building what does not exist yet and looking towards a new horizon.

Greenhouse, Portugal Pavilion, 2024. Artnet News.

Hosted in the stunning location of Palazzo Franchetti, overlooking the Accademia Bridge and Grand Canal, Portugal’s Greenhouse merges sculpture, stage, installation, and assembly spaces into a “Creole garden.” The curatorial and artistic team, Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges, Vânia Gala (a visual artist, a researcher, and a choreographer), organizes collective actions, using pedagogy, sound, and movement, to reflect on the relationship between nature, ecology, and politics. In doing so, the garden becomes a space for diversity and interaction, questioning how soil, land, and borders connect with contemporary politics of the body and foster ecologies of care. Through four actions (Garden, Living Archive, Schools, and Assemblies), the pavilion facilitates experimentation and reflection on interconnected themes that affect us globally.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!