Summary

- Indigenous Australian culture has a history spanning millennia and its traditions have been passed on through many generations. Because of Australia’s geography, its indigenous cultures are very unique and distinct from one another.

- The Dreaming is the worldview of Indigenous Australians – their mythology, cosmology, law, history, and map. It differs among different indigenous groups.

- Without formal written language, images are key for Indigenous Australians. Many indigenous groups share similar visual symbols.

- Aboriginal artworks consist of layers of meaning, from the one directed to children to a spiritual one. They tell a story about a particular indigenous group and land – for example the Djaru people often include Wolfe Creek Crater in their works, while the Anangu people portray Uluru.

- The ancient Serpent is believed to have created (through its movement) the Earth, nature, and life-giving water. After the storm he appears as rainbow while he crosses the sky. Thus he is one of the most common motifs across Indigenous Australian art.

First Australians: A Long History

Aboriginal people are the local inhabitants of Australia, whose arrival and development in the country remain unclear to this day. The remoteness of this land and its inhospitality allowed them to evolve in their particular way, without external influences. Moreover, each group of Australia’s First Nations peoples developed differently because of the extremely large distances between the settlements.

A very curious characteristic of their culture is a whole range of ancient traditions, stories, and rituals handed down from father to son, from mother to daughter, which stayed practically unchanged for centuries. Even more curiously, each group shared their proper traditions and stories, often different from those of other groups, although invariably linked to the local mythology. A common feature is that every Indigenous Australian has always been very guarded about their traditions. So, what we now know is only a partial vision of the whole story – or stories. It is just what they think can be shared with non-Aboriginal Australians.

Today Australia’s First Nations people are considered a respectful part of the society, representing 3.2% of the total population. Although when Europeans came to Australia in the 18th century, they mistreated the local people. Many First Australians died in armed conflicts, were deprived of their lands, and were often obliged to be confined. Their culture was being destroyed and looted. In 2008, the Prime Minister of the Australian government officially apologized, particularly to the Stolen Generations whose lives had been blighted by past government policies of forced child removal and assimilation. Since 1995, the Australian Aboriginal flag and the Torres Strait Islander flag have been official flags of Australia. Also, Indigenous art and culture get more interest and esteem.

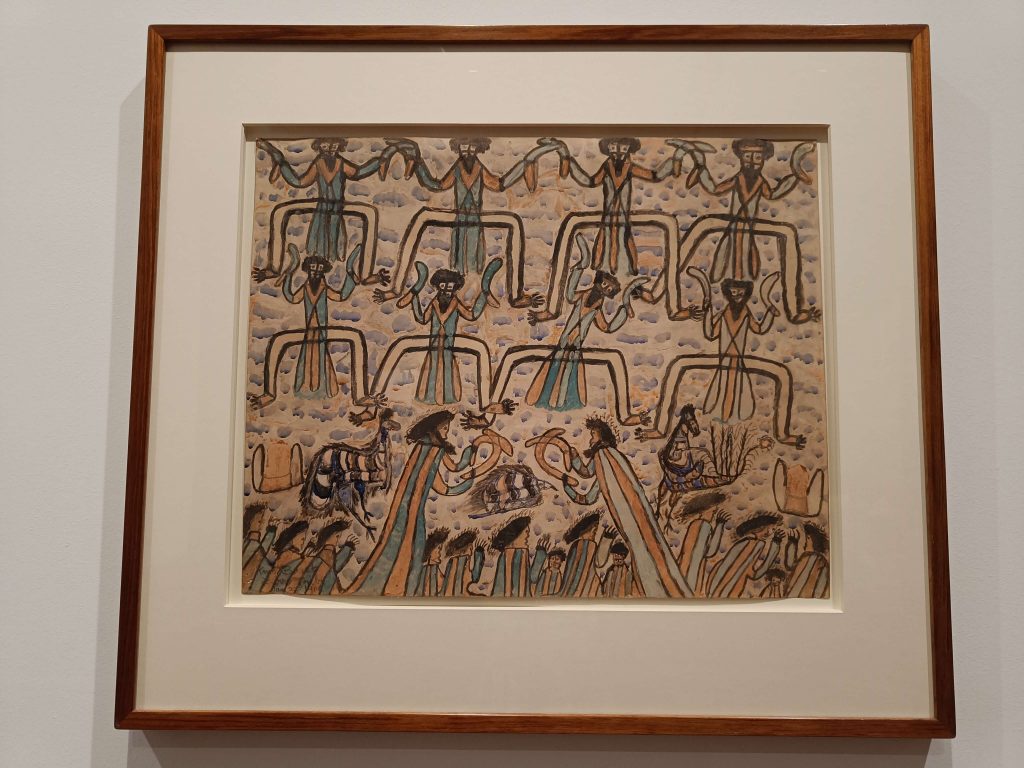

William Barak, Untitled (Cerimony), 1900, The Ian Potter Center: NGV Australia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. Photographed by the author.

Aboriginal Mythology

The anthropologist Bill Stanner (1905–1981) believed that the Aboriginal word translated into English “dreaming” could mean many different things such as “totem”, “totem site”, or the “time of marvel in the indefinitely remote past.”

Interestingly, Indigenous Australian traditional stories about the world’s origin, the people’s evolution, and their gifts, as a whole called “Dreamtime” or “Dreaming”, are effectively everything that could be considered as a basis on which people should live. They are the background, the source, and the moral compass that guides and gives meaning to life. In other words, we could consider the Dreaming as mythology and cosmology, but also as law, history, and a map of the land. Why maps? Because for Australian First Nations, a particular unusual characteristic of the land can be considered a sign that something important has happened in that place. They also believe that an ancestral power is left behind in such places and thus they become central points for their culture, mythology, and rituals.

Therefore, stories of the Dreaming are often inscribed onto the particular features of the land and they only have meanings when linked to the traditional land of a particular group. In this way, for Indigenous Australians, the landscape is filled with messages which are secret and sacred and cannot be revealed to non-members of the group. People who share the same Dreaming are bound socially and ritually to each other and to their land. Moreover, almost invariably it is forbidden to claim and represent in any form the Dreaming of another group.

An artist realizing a traditional dot painting. Kate Owen Gallery.

Indigenous Australian Art: Symbols

Indigenous Australians did and do not have a formal written language. Subsequently, the production of artworks plays a central role in their culture. Without writing, the only way to maintain history is through visual production, pictures take the place of words.

As far as it concerns the spoken form, each Aboriginal group has a different dialect. Today there are about 500 different Indigenous Australian languages. Therefore, each group has different pictures linked to it and unsurprisingly there are also many varieties of techniques. Meanwhile, each individual artist has also their own personal signature, a reflection in themselves of the stories of their Dreaming.

We now know that some traditional symbols are shared among different groups. For example, a shape with multiple concentric circles means “waterhole”, a half-moon shape stands for “campsites”, whereas the U shape represents a person. Generally, the U with one line at its side is a woman, with the traditional stick she carries to search for water and resources in the sandy soil. The U with a sort of flat V stands for a man: a person with a boomerang, used for hunting. The V shape with a line in the middle recalls the footprint of an emu. These symbols can be found in many traditional sites where fathers still teach sons as their Ancestors used to do. They are also often reported in modern paintings.

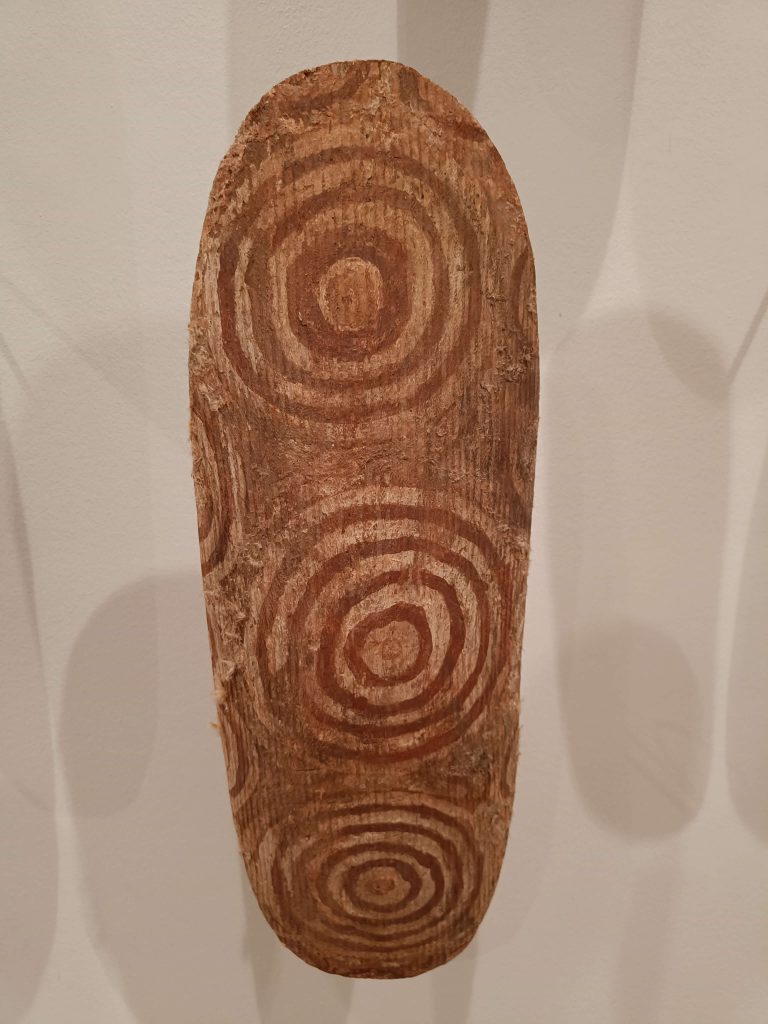

Symbols from 30 000 BCE to today, Caves in Uluru, CA, Australia. Photographed by the author.

Indigenous Australian Art: Authenticity

Although these symbols may be a (more) common feature among groups, as already said each one has its own Dreaming. In fact, artists only painted and paint their country or that of their parents. Therefore, each painting or artwork tells a story about the land and the group’s Dreamtime and comes with an interpretation and “signature” of the artist. These are specific artists’ identifying features and guarantee that the art is authentically made by the First Nations artists. A non-Indigenous Australian does not have the authority to paint an official Aboriginal piece of artwork. It may copy the style but it will never be authentic, certified Indigenous work.

To further explain, “paintings of the land” means that the artists painted their vision of some aspect of the cosmological and ancestral meanings associated with the country of their birth, or that of their immediate ancestors. They painted the stories told to them by their families, even though they may not have had direct experience with that territory because they had been dispossessed or forced to leave the region in which they or their parents were born.

In addition, if they wish to paint a story concerning strongly historical or sacred information, they must be given permission before they can proceed.

Paintings created by First Nations artists in the Gallery of Central Australia (GOCA), CA, Australia. Photographed by the author.

Meanings and Modern Developments

Like art in general, the Indigenous Australian artistic form may have multiple layers, each speaking to a different audience. The first, “superficial” level is often directed to children or the public in basic form. Then, there’s a second, more refined layer that speaks to a general audience, mainly adults, in a deeper form. The last and deepest level concerns a spiritual and/or ceremonial meaning. An Aboriginal artist should comprehend all three layers to represent the visual story in the most comprehensive form possible.

Over the centuries, Australian First Nations conveyed their specific Dreaming on various surfaces, from wood to stones and bodies. As a result, you can find historical Aboriginal artworks in museums other than paintings: often boomerangs, didgeridoos, and shields carrying typical symbols, patterns, and colors. However, today they mostly use canvas. They have perfectly adapted to new mediums to express their art, without losing a single aspect of the traditional subjects and histories.

Nowadays, there are many museums and art galleries throughout Australia which host Indigenous manufacturers and craftsmen. They are often referred to as artworks of the First Nations and can be found, for example, at the Australian Museum in Sydney, and at the Ian Potter Center: NGV Australia in Melbourne. Galleries completely and exclusively dedicated to Australian Indigenous art are also in development, such as the Gallery of Central Australia (GOCA), in the traditional and ancestral site of Uluru, also called Ayers Rock; and like the Kate Owen Gallery in Rozelle, hinterland of Sydney.

Different Dreamings: Wolfe Creek Crater

As aforementioned, different techniques can be found according to different groups’ traditions and Dreamings.

One of the most famous styles is dot painting, although it is not the only one existing, as many non-Australians may think. Dot painting seems to have originated from the time of European settlement when Aboriginal Australians feared that non-Indigenous people could understand their secret knowledge and culture in general. Double-dotting hid any form of meaning but was still understandable to First Nations people. Nowadays it is particularly loved because of the balanced composition it gives to paintings.

But what does “different Dreamings” mean? Two examples can be used to explain this concept. On the one hand, the huge Wolfe Creek Crater in Western Australia called Kandimalal in the language of the Djaru people, has a combination of stories linked to it. A very interesting one that tells about the origin of the crater is as follows. Once upon a time, the crescent moon and the evening star passed very close to each other. The evening star became very hot and fell to the ground. An unprecedented explosion, with flash, dust, and loud noise frightened the Australians. Only after some time, they came to look, realizing that the crater was the site of the falling star. The symbol of the star became central in the art created by the Djaru people.

Wolfe Creek Crater, Great Sandy Desert, WA, Australia. Photo by Dainis Dravins – Lund Observatory, Sweden, via The Conversation.

Different Dreamings: Uluru

On the other hand, Uluru, the huge sandstone red rock in Central Australia, also called Ayers Rock, has its own Dreaming stories which always point to this particular landscape.

Uluru is said to have been created at the beginning of time by ten Ancestors, or spirit people of the local group, the Anangu people. The Dreaming narrates this story: the world was a flat, monotonous place. The ancestors of the Anangu arrived and traveled across the country, creating its characteristics like Uluru. Today, Uluru remains sacred to many Indigenous Australian groups who still perform rituals in its proximity and realize new paintings on the rocks.

Uluru, or Ayers Rock, CA, Australia. Photographed by the author.

Common Features

Although every Indigenous group has its own Dreaming, some stories or “characters” are shared among all or almost all of the groups. These may represent the most ancient traditions, conserved and handed down for millennia. Of course, these shared stories vary slightly between groups because they were adapted to the landscape, culture, and specific climate of a single group. However, the main characters and the meanings stay the same.

The Rainbow Serpent

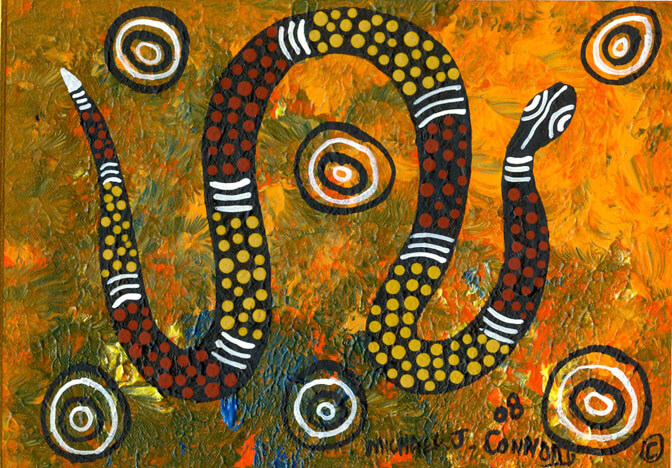

The most interesting and famous is that of the Rainbow Serpent, also called Eternal Serpent. It seems to be one of the oldest continuous religious beliefs in the world.

The Serpent was one of the Dreamtime creatures, extremely powerful. He emerged to give shape to an ancient, featureless Earth. He awoke different groups of animals, and his movements created physical features like hills, creeks, waterholes, and rivers. The creation of water, life-giving but so difficult to find in Australia and thus so precious, underlines the positive role of the Eternal Serpent. Once he was tired of modeling Earth, he coiled into a waterhole where he is said to lay still today. First Nations people never disturb water sites where the Serpent could be. In fact, he can be unpredictable at times, causing great destruction through water (floods, drought, and cyclones). During rainstorms, people should stay away from waterholes. After the storm, when the sun comes out again, the light reaches his body, which is rainbow-colored as his name says. He becomes visible as a rainbow while he crosses the sky traveling from one waterhole to another, to refill this one too.

As said, there are slightly different creation stories of the Serpent in different regions and he is given different names but his representation is practically ubiquitous all around Australia. For example, two different versions of the Kandimalal explain that in the Crater a Rainbow Serpent once took up residence, or even that a Serpent was the being that fell from the sky, not a star. Meanwhile, at Uluru, the Serpent is called Wanampi, and it is mandatory to shout at the Ancient Being before approaching and to remember that he will never come close to the fire.

Michael J Connolly, Munda-gutta Kulliwari (The Rainbow Serpent), 2008, Dreamtime Kullilla Art.