From Victim to Temptress: Salome in Art

For centuries, artists interpreted the biblical story of Salome and turned it into a lasting theme in art. But where did this fascination come from?...

Edoardo Cesarino 22 January 2026

Though Kandinsky and Malevich came from different backgrounds, their paths converged in shaping the Russian avant-garde. Each developed a radically new visual language, and together they became pioneers of early abstract art. How did these two visionary artists embrace abstraction almost simultaneously? Their journeys weren’t identical, but shared striking parallels. Let’s explore the inspirations, philosophies, and visual strategies behind their most iconic works in the years leading up to Russia’s 1917 Revolution—a moment of radical artistic reinvention.

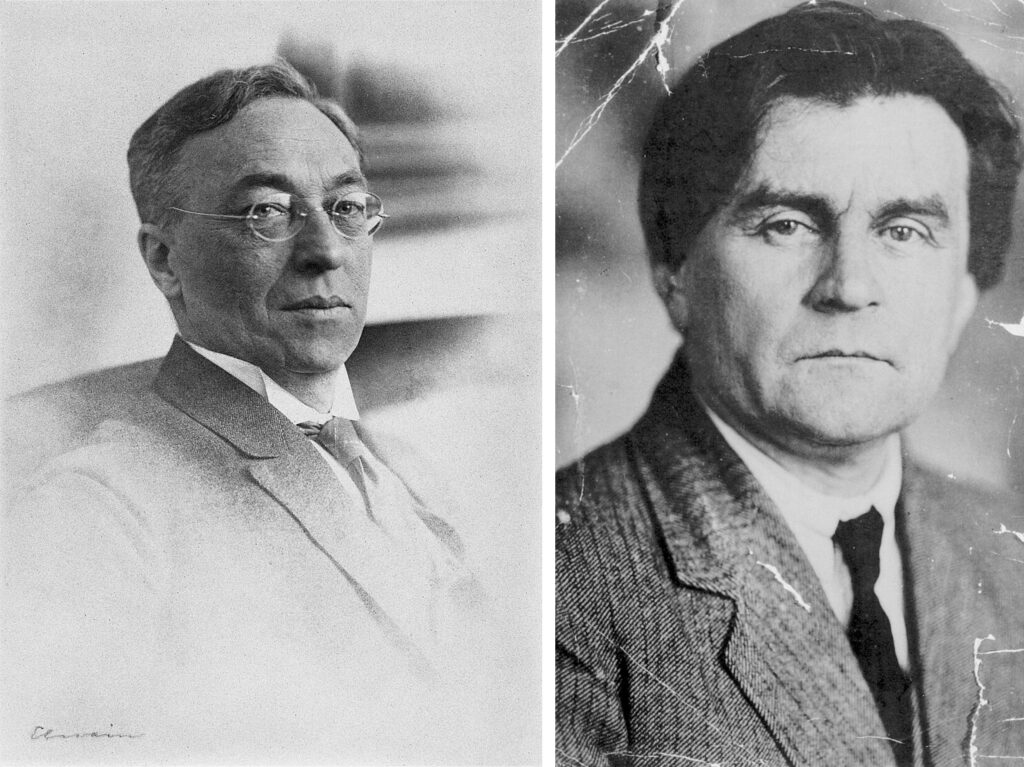

Left: Wassily Kandinsky, 1925. Photograph by Adolf Elnain. Wikimedia Commons (public domain); Right: Kazimir Malevich, c. 1925. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

In their early work, Kandinsky and Malevich absorbed the vibrant currents of European modernism. After encountering the French collections of Russian art collectors Shchukin and Morozov, Malevich produced pieces that echoed the styles developed by the French avant-garde of the early 20th century, such as Impressionism, Fauvism, and Pointillism. Malevich’s Bather (1911), for instance, shows striking similarities with Matisse’s dancers in La Danse.

Kandinsky, meanwhile, gravitated toward Expressionism and Fauvism, as seen in his 1908 painting Blue Mountain, with its strong colors, dark contours, and flat shapes. Yet what ultimately propelled them beyond figuration was not just visual influence. For Kandinsky, it was music; for Malevich, language. These deeper forces shaped their paths toward abstraction in profoundly different ways.

Wassily Kandinsky, Blue Mountain, 1908, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

Kandinsky experienced synesthesia, a condition that allowed him to perceive sounds as colors. This deep sensory connection made music a natural gateway to abstraction. Since music is inherently non-representational, Kandinsky saw it as a model for painting—using color and form to evoke the same emotional resonance that music stirred in him. He believed in the psychological and spiritual effect of color and music. It is no surprise then that in his seminal treatise, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky used the analogy of music to explain the importance of color:

Color is a means of exerting a direct influence upon the soul. Color is the keyboard; the eye is the hammer. The soul is the piano, with its many strings. The artist is the hand that purposefully sets the soul vibrating by means of this or that key.

Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 1910.

This musical analogy extended to the titles of his abstract works, many of which—Compositions, Improvisations, Impressions—borrowed directly from the language of music, underscoring his belief in art’s capacity to resonate like sound.

The music of Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg had a profound impact on Kandinsky, particularly through its free tonality, complex harmonies, and dissonant structures. Schoenberg’s break with the traditional musical canon encouraged Kandinsky to pursue a similar rupture in painting—moving away from representational conventions toward abstraction. His Impression III (Concert), painted in 1911 after attending a Schoenberg performance, marks a clear step in this direction, translating sound into visual rhythm and emotional intensity.

Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert), 1911, Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany.

Malevich, by contrast, immersed himself in the linguistic experiments of the Russian Futurists, who were developing a transrational language known as zaum. Their goal was to dismantle conventional meaning in language, forging a direct link between sound and emotion through pure rhythm and phonetics. Inspired by this radical approach, Malevich pursued a similar revolution in painting, stripping the representation of objects of their meaning.

He created “alogical” paintings, where representation was emptied of meaning, allowing depicted elements to acquire a new, purely painterly value. The influence of the zaum philosophy is visible in paintings such as An Englishman in Moscow of 1914, where objects and words collide in a deliberately nonsensical arrangement, challenging viewers to see beyond logic and language.

Kazimir Malevich, An Englishman in Moscow, 1914, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Beyond modernist experimentation, both Kandinsky and Malevich found inspiration in old Russian folk culture, which gained renewed prominence during the Slavic Revival movement at the close of the 19th century. Lubki—Russian popular folk prints—became central visual references in their work, though each artist interpreted them differently on the canvas, infusing tradition with their own modernist sensibilities.

Kandinsky’s background in ethnography fueled a deep fascination with Russian folklore, especially its spiritual and shamanistic dimensions. He drew inspiration from Russian fairy tales and lubki, infusing his early works with their vivid imagery and symbolic resonance. This influence is clear in paintings like Colorful Life (1907), where folkloric themes meet a dreamlike color palette.

Wassily Kandinsky, Colorful Life (Das Bunte Leben), 1907, Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany.

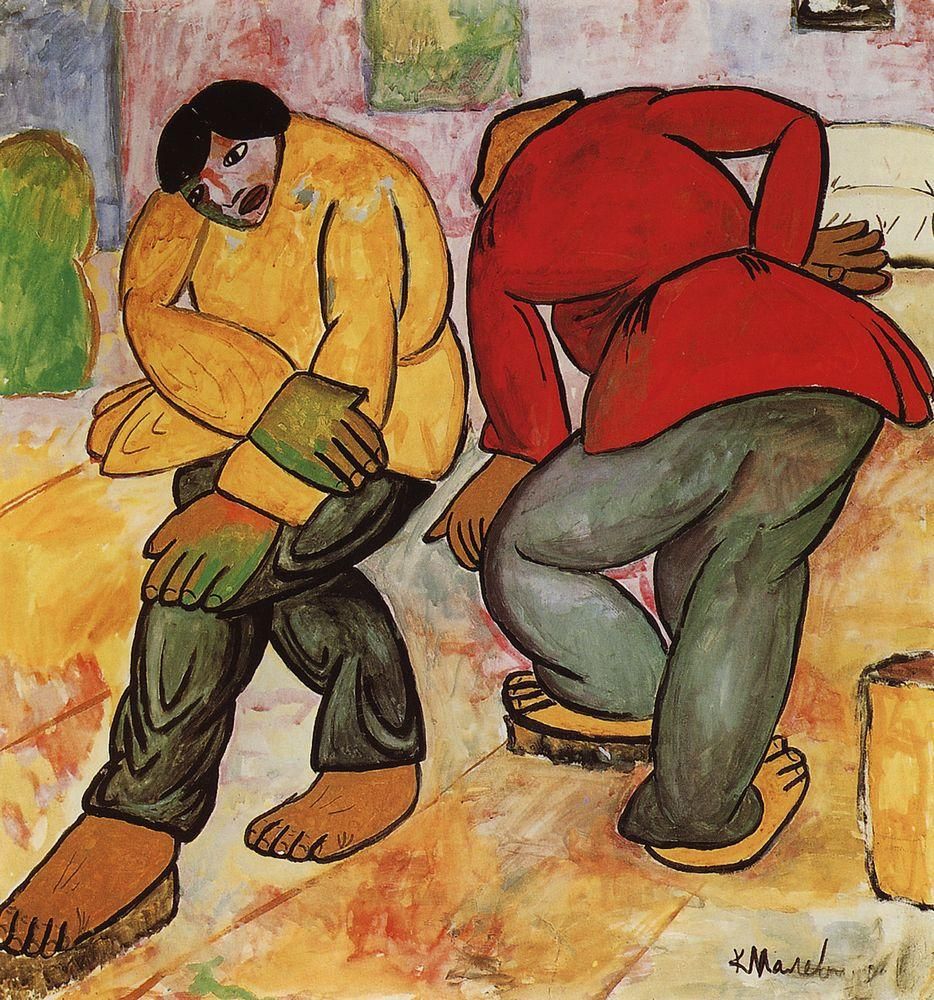

Malevich also found inspiration in lubki, particularly during his Neo-Primitivist phase. Works like The Floor Polishers (1911) reflect his fascination with folk art and the peasant figure, whose creative spirit he deeply admired. This admiration would later evolve into a recurring theme in his figurative paintings, where the peasant would become a symbol of cultural authenticity and artistic renewal.

Kazimir Malevich, The Floor Polishers, 1911, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Beyond external influences, both artists found profound resonance in a distinctly Russian visual tradition: the icon. More than a visual reference, it became central to their artistic philosophies—though, once again, each interpreted its significance differently, reflecting their distinct theoretical approaches.

Kandinsky’s approach to abstract art was deeply spiritual and reflected the painter’s interest in theosophy, mysticism, and shamanism. He considered that art was meant to be the expression of the inner essence of man—an intuitive core that could not be translated into words or represented figuratively. In this view, artistic abstraction became a necessity to reach the spiritual, while the artist was to be the shaman or the prophet who would help bring the spiritual into this physical world.

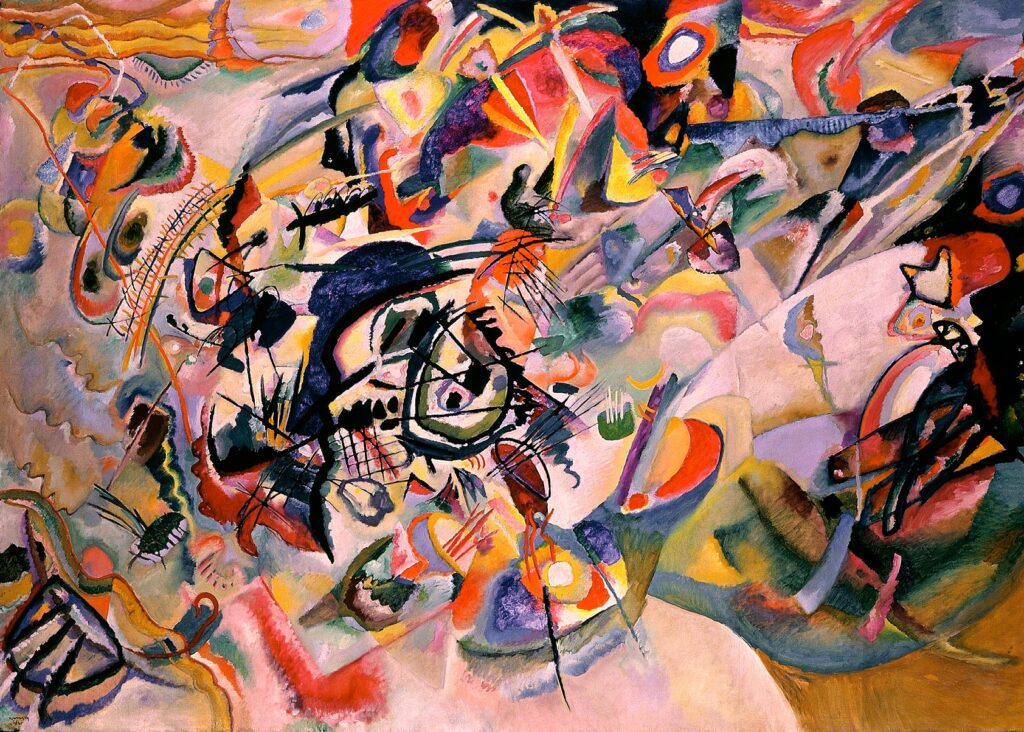

In that respect, old Russian icons had a profound impact on Kandinsky’s thinking. Like his own work, icons weren’t designed as Albertian windows onto the world, but as portals to the spiritual realm. The influence of the icon can be seen throughout Kandinsky’s oeuvre and his frequent use of religious iconography. Even in fully abstract pieces like Composition VII (1913), themes such as Resurrection, the Last Judgement, and the Deluge can be identified.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.

Malevich’s theory of Suprematism, on the other hand, was not related to the spiritual realm—at least at first glance. He envisioned Suprematism as the foundation of a new, objectless artistic culture—one that rejected representation altogether in favor of pure form. In his treatise From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism, the artist posited Suprematism as the “new artistic culture” where art would be an end in itself, without the need to copy nature or the need for a subject matter. He heralded the beginning of a non-figurative, non-objective art as the utmost and purest form of creativity, liberated from the shackles of representation.

However, most interpretations of his most famous Suprematist work, Black Square, point to a spiritual dimension—echoing Kandinsky’s own approach. The painting’s symbolic connection to the Russian icon is unmistakable: at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0,10 in 1915, it was placed in the upper corner of the room, mirroring the traditional krasnyi ugol or “beautiful corner” where icons were traditionally displayed in Russian homes. Malevich himself reinforced this reading, famously calling Black Square “an icon of [his] time.” In fact, Malevich envisioned his “new artistic culture” not just as an aesthetic shift but as a new spiritual movement—with himself as its prophet.

Going deeper in the religious analogy, British art historian Susan Compton interpreted the Black Square in the light of the mystical idea of the fourth dimension proposed by Russian religious thinker P.D. Uspensky. In Uspensky’s theory, there existed a fourth dimension that contained the three-dimensional world that humans were living in, and this fourth dimension represented the higher consciousness of humankind.

This idea was certainly familiar to Malevich, as it was of great interest to his friend Kruchenykh, with whom he had worked on the opera Victory over the Sun. The notion of a transcendent dimension resonates with Kandinsky’s belief in an inner essence or intuitive core of the human spirit. Interpreting Black Square through this lens suggests that, despite their differing approaches, both artists were engaged in a shared spiritual pursuit through abstraction.

Though their paths to abstraction occasionally overlapped, Kandinsky and Malevich ultimately arrived at very different destinations. Kandinsky embraced a non-geometrical form of abstraction, distancing himself from representation but never fully abandoning it. For him, art remained a vehicle for emotional and spiritual expression—a way to communicate inner experience. Malevich, by contrast, broke entirely with representation. His vision led to a stark, geometrical abstraction where pure form reigned supreme. What’s striking is that even after the upheaval of the 1917 Russian Revolution, both Kandinsky and Malevich—key figures in the rise of abstraction—occasionally returned to figurative art. Beneath their radical innovations lay a quiet pull toward representation, suggesting that their break from tradition was never total, but part of a deeper, ongoing inner dialogue between image and idea, form and meaning.

Art in Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Ed. by Charles Harrison & Paul Wood, Oxford, 1992.

Kandinsky: The Path to Abstraction, Ed. by Hartwig Fischer, Sean Rainbird, London, 2006.

Kazimir Malevich: The Black Square, Ed. by Friedemann Malsch, Cologne, 2019.

Susan P. Compton, “Malevich’s Suprematism—The Higher Intuition”, The Burlington Magazine, 1976, Vol.118 (No.881).

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!