Clouds in Art—Stratus, Cumulus, Cirrus, and Many More!

Clouds in art are why the term “landscape painting” is a bit deceiving. It suggests that the subject of the artwork is the land, and yet it is...

Sandra Juszczyk 25 July 2024

Marcus Aurelius, the last of the five good Roman emperors once wrote: “The best way to avenge yourself is not to become as they are” (Meditations 6.6). When one reads Aeschylus’ well-known trilogy, Oresteia, it will become clear that all the mortal deeds and motives within these plays were built upon the values which were against the stoic emperor’s statement. A single action causes a series of intertwined bloodshed where the divine present themselves as both the perpetrators and judges. Do you wonder how that even came to pass? You are in the right place then! Let’s see how painters from around the world portrayed the acts in Oresteia and observe how the events unfolded.

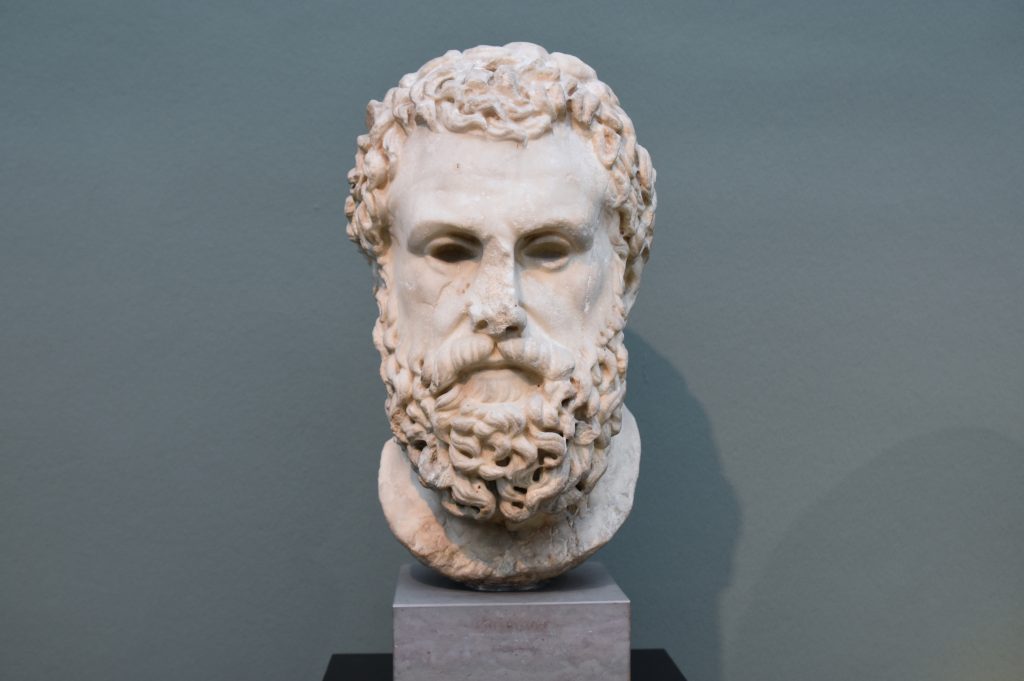

The eldest of the three great tragedians, Aeschylus, was born around 520s BCE into an aristocratic family residing in Eleusis. During his youth, he witnessed the creation of the first democratic rule after the expulsion of the Pisistratids. Throughout his lifetime, not only did he see major conflicts that played out between the Greeks and Achaemenid Empire, but he also fought in them. He faced the Persians both at Marathon and in the sea battle of Salamis. From the 490s BCE onward, he produced one of the best examples of tragedies until his death.

Literary evidence indicates that he authored more than 90 plays throughout his lifetime, yet, only six survived. One of them is Oresteia, the trilogy where we witness the downfall of mighty ruler Agamemnon and his wife Clytemnestra. What makes Oresteia even more special is the three tragedies are the only connected trilogy that was able to withstand time’s withering nature. As the pinnacle of dramatic sophistication, Aeschylus inspired and fascinated countless minds for centuries; unsurprisingly, painters were among them. Their creations let us internalize the narrative even more deeply.

He endured then to sacrifice his daughter in support of war waged for a woman, first offering for the ships’ sake.

Aesch. Ag. 223-227

All the battle preparations having been made, the Achaeans were ready to sack Ilium and take back the wife of Menelaus, Helen of Sparta. Naturally, to achieve this goal, they had to cross the Aegean Sea, but the divine desired to see how dedicated they were to begin this campaign that would last 10 long years. In many versions of the myth, it is indicated that the Greeks were stuck on the shore of Aulis located on the mainland. This was due to the lack of wind required to have the army reach Asia Minor.

Right this instance, the seer Calchas informed King Agamemnon and told him that the goddess, Artemis, demanded the sacrifice of Iphigenia, the eldest daughter of the king. Agamemnon in shock, asked himself:

How shall I fail my ships and lose my faith of battle?

Subsequently, he carried out the deed through conflicting emotions. Little did he know that it was this deed that would lead to his ruin.

These three different paintings portray the exact moment within Oresteia where the father sacrifices his daughter to appease the goddess and, consequently, restore the honor of the Greeks by waging war.

In the sky, we see the goddess Artemis with a deer; this can be interpreted in two ways. Firstly, the deer is in the composition due to the symbolism as it is one of the most important animals associated with the goddess. Another interpretation relies on the different versions of the myth, where Artemis saves Iphigenia seconds before she was sacrificed and gave Agamemnon a deer instead. However, it is important to note that in Oresteia, Iphigenia dies so that this terrible event could provide Clytemnestra with a pretext to counteract.

The compositional positioning of the figures is relatively similar with a few significant exceptions. In Bertholet Flemalle’s piece, the deed is being carried out by Agamemnon himself, while the seer Calchas, with his golden staff that emphasizes his wisdom, is on the left of the altar. Flemalle also included geographical elements such as the shore, which demonstrates to the observer that this is the beginning of a journey.

On the other hand, in Perrier’s work, Agamemnon is the one who gives the order for sacrifice but is not the one who carries out the deed itself. We see him with his gold crown, pointing his finger to the altar. Calchas is not in the composition as every figure in the piece is too young to be him. Instead of him, we see a woman praying to the goddess on her knees who could be Clytemnestra. Lastly, have you noticed something unusual about the clouds? They have small faces that blow wind! A good way for Perrier to let us know what Artemis is gatekeeping, wouldn’t you agree?

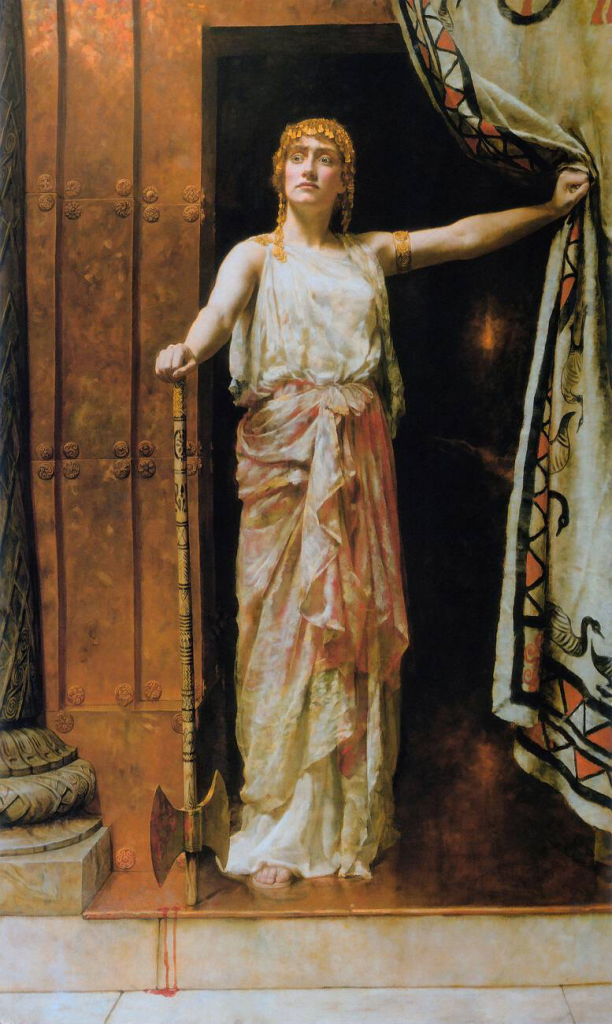

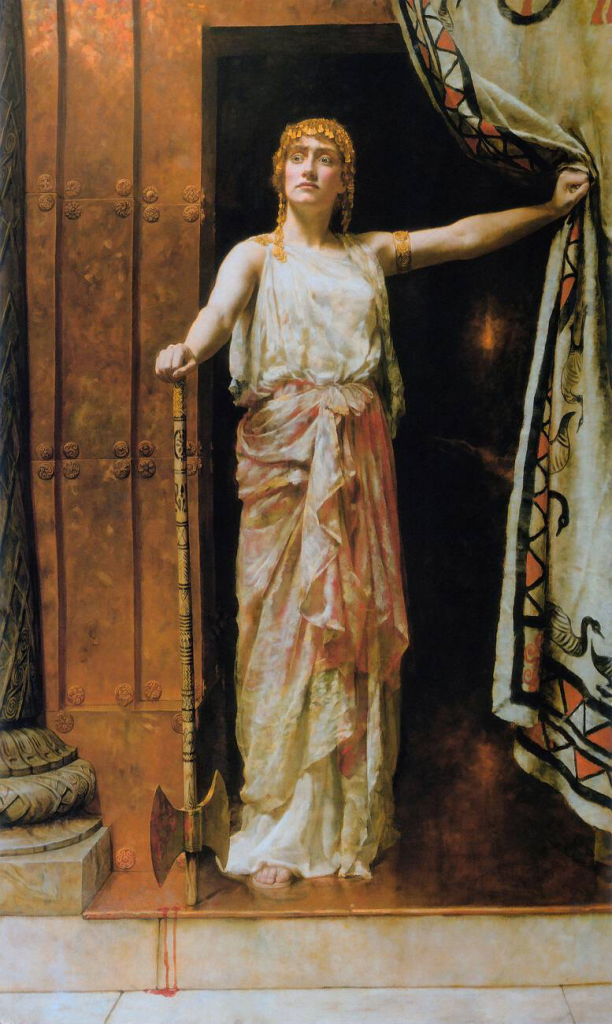

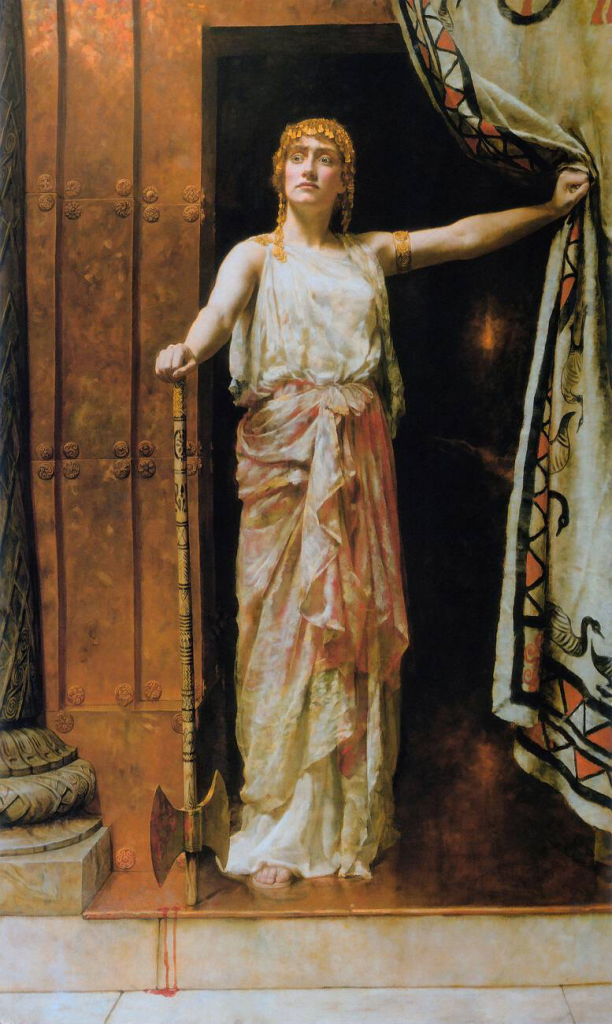

I stand now where I struck him down. The thing is done. Thus have I wrought, and I will not deny it now.

Aesch. Ag. 1378-80

There is no doubt that John Collier is one of the first artists who come to mind when we talk about the representation of Clytemnestra in visual arts. His portrayal of Clytemnestra fits Aeschylus’ narrative so well that if Collier had never created these pieces, the image of Clytemnestra in my mind would still be almost the same as his paintings. In both of them, we see Clytemnestra right after she killed her husband, Agamemnon, while he was taking a bath. Certainly, the portrayal reflects not before but the aftermath of revenge, for the blood that drips from her weapon and her powerful posture evidently affirms it. In Oresteia, Aeschylus does not specify what type of weapon she used, but he indicates that Clytemnestra struck him three times. She also killed the Trojan priestess, Kassandra, who foresaw all these events which came to pass.

Clytemnestra stands gloriously in front of a doorway in a proud and satisfied manner. In the 1914 version, the architectural details within the house of Agamemnon are more emphasized. It seems that the artist was inspired by archeological findings when it comes to the patterns on the column, the gate, the floor, and the stairs. Additionally, Clytemnestra’s dress and garments are more subtle and richer in detail. The other significant difference in the latter version is Collier’s approach in depicting Clytemnestra’s facial features. In the first interpretation, the subject’s countenance is more idealized. On the other hand, in his second interpretation, Collier’s Clytemnestra has a beautifully defined chin and nose. Her eyebrows are in a more natural state and the overemphasis of blush on her cheeks is absent. Personally, all these characteristics are in coherence with the image of Argos’ queen in my mind.

Die then and sleep beside him, since he is the man you love, and he you should have loved got only your hate.

Aesch. Lib. 906

These were some of the last words of Orestes right before he killed his mother to avenge his father. With the encouragement and instruction of Apollo, the exiled son of Agamemnon returned to Argos undercover and successfully killed both his mother and her lover Aegisthus who hated Agamemnon all along because of the old conflict between his dad Thyestes and Agamemnon’s dad Atreus.

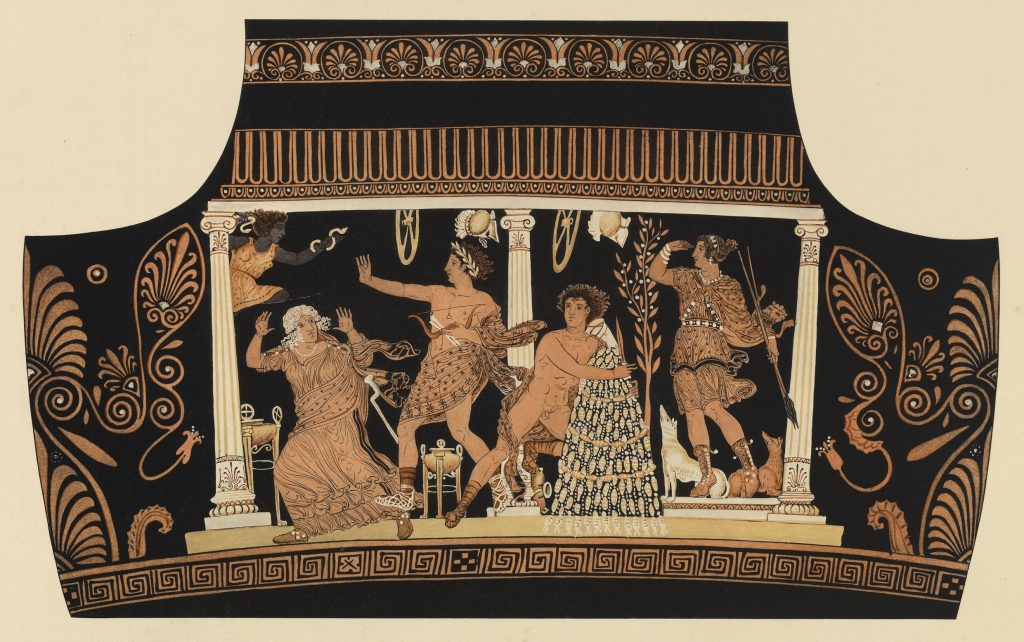

We see Orestes in beautiful armor, holding his mother’s hair and ready to strike a final blow to end her rule in Argos and make her pay for what she did to Agamemnon. The dead body under Orestes is Aegisthus who experienced Orestes’ fury first. Clytemnestra has an expression of terror while Orestes seems confident and satisfied with this deed. Yet, he isn’t aware of the Erinyes, commonly known as the Furies, who are chthonic deities of vengeance. They are ready to pursue and make Orestes suffer by haunting him as long as he breathes for the matricide he committed.

Bernardino Mei, an Italian painter who lived in the 17th century flawlessly depicted this brutal climax from the trilogy of Oresteia. One instantly feels the dread within the piece after observing the painting, even if it is for a short period. A mother who has seen her daughter sacrificed is now getting murdered by her other child mercilessly; an incredibly powerful and touching harmony of Greek tragedy and Baroque art.

We are the eternal children of the Night. Curses they call us in our homes beneath the ground.

Aesch. Eum. 415

After Orestes killed his mother, the Furies began to torment him wherever he went. Having realized that he will not be able to escape or resist them, he sought refuge in the Sanctuary of Delphi to ask Apollo for his salvation. When he arrived at the sanctuary in an exhausted state, followed by the Furies, Apollo put the Furies into a deep sleep until they were awoken by the enraged ghost of Clytemnestra. But before they were awakened, Apollo swiftly sent Orestes to Athena, for she alone could bring justice to this chaotic revenge tale.

This masterpiece created by Bouguereau is arguably one of the most well-known paintings that focuses on an Oresteian episode. Bouguereau flawlessly conveyed the emotion of being terrified through Orestes’ expression. His eyes are wide open and teary. He tries not to hear the voice of the Furies by putting his hands over his ears, yet, it seems that he is not being entirely successful. As for Clytemnestra, we see her in the arms of one of the Furies and with a dagger thrust right through her heart.

In Oresteia, Aeschylus described the Furies as repulsive and dark divinities. He indicated that their dresses were incredibly wicked and that one would not be able to wear them in front of another human being. He also states that a mysterious ooze drips from their eyes. Evidently, Bouguereau desired to take some liberties in interpreting them. He portrayed the Furies by relying on his imagination and creativity rather than sticking strictly to ancient literary texts. This decision contributed to the unfolding of the artist’s perspective in an unconstrained way.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!