Masterpiece Story: The Setting of the Sun by François Boucher

With sweet putti, handsome gods, beautiful nymphs, vibrant colors, and elaborate compositions, The Setting of the Sun is a testimony to François...

James W Singer 8 February 2026

28 December 2025 min Read

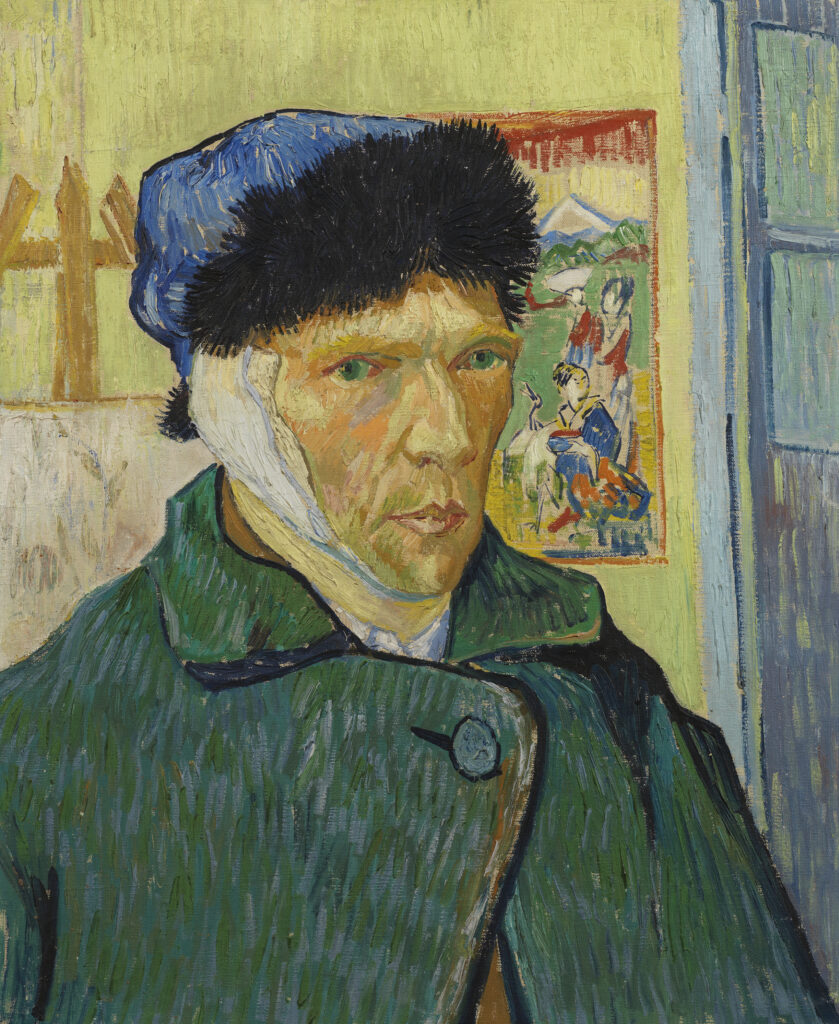

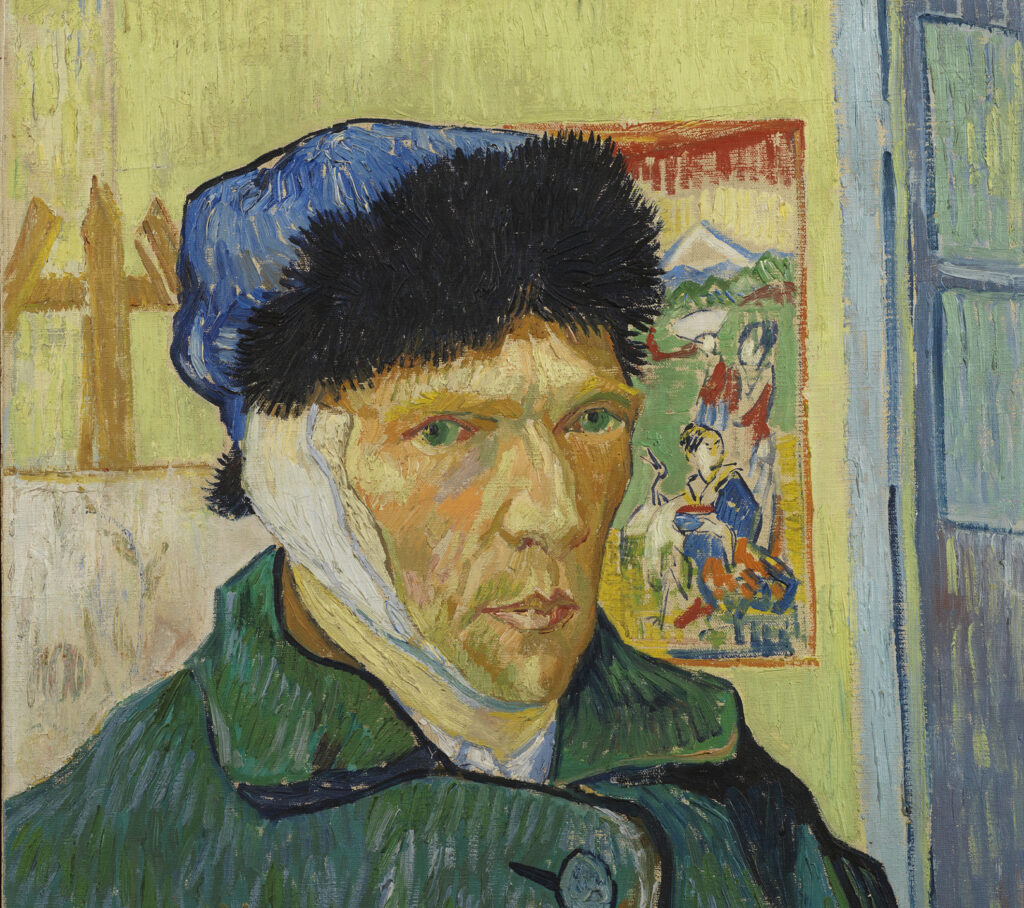

Vincent van Gogh left behind a series of self-portraits that document his life—from an aspiring artist through stylistic change, all the way to the tragic end. These works reveal much about his mental state at each stage of his life. Let’s focus on one of them. Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear encompasses Van Gogh’s life story in one frame.

Van Gogh was a Dutch Post-Impressionist, now admired worldwide for his distinctive style. Though it was not always this way. Born into a middle-class family, he did not lack much as a child. Adulthood, however, brought hardship and constant struggle to achieve success as an artist. After failing to become a pastor, his brother Theo convinced Van Gogh to take up painting. He practiced by painting still lifes and peasant life.

Following several unsuccessful romantic endeavors, Vincent eventually ended up in Antwerp. There, his living conditions worsened. Though supported by Theo, he lived in poverty, spending most of his money on art supplies. Throughout the rest of his life, Van Gogh struggled financially.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Van Gogh’s paintings weren’t always as bright or colorful as the ones we adore today. During his years in the Netherlands, his work relied on dark and muted shades of brown. His style shifted only after moving to Paris in 1886. There, he encountered many great artists, like the Impressionists. Their influence transformed his approach to art. His brushwork grew looser, and he adapted Pointillism into his own style. At the same time, his fascination with Japanese prints also continued.

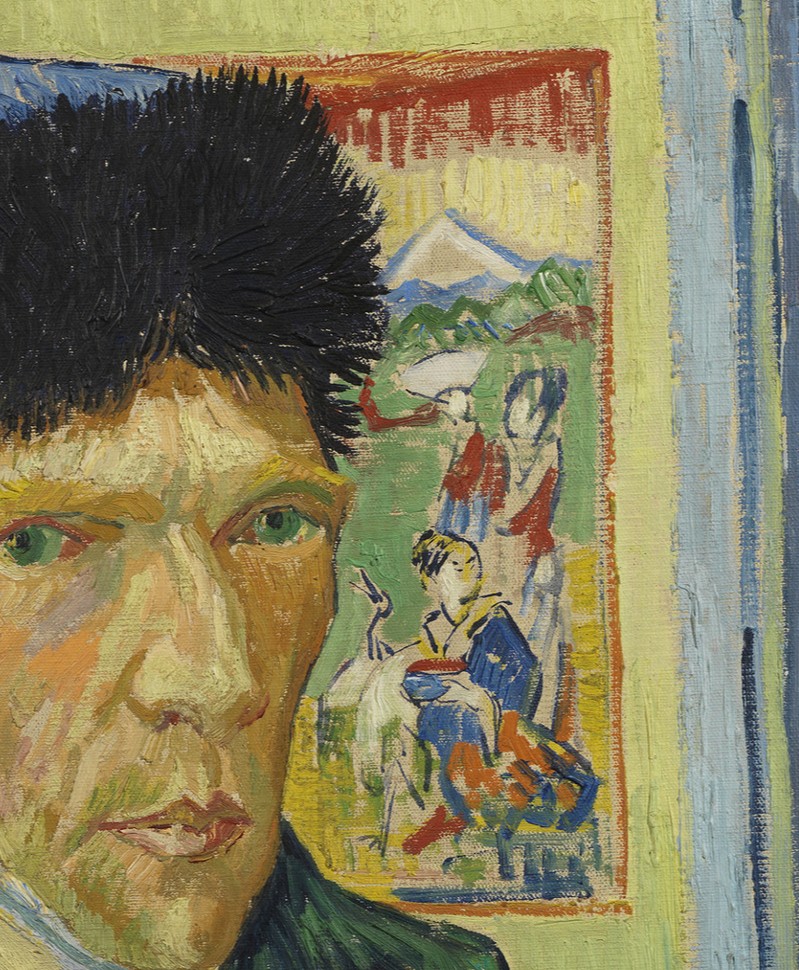

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

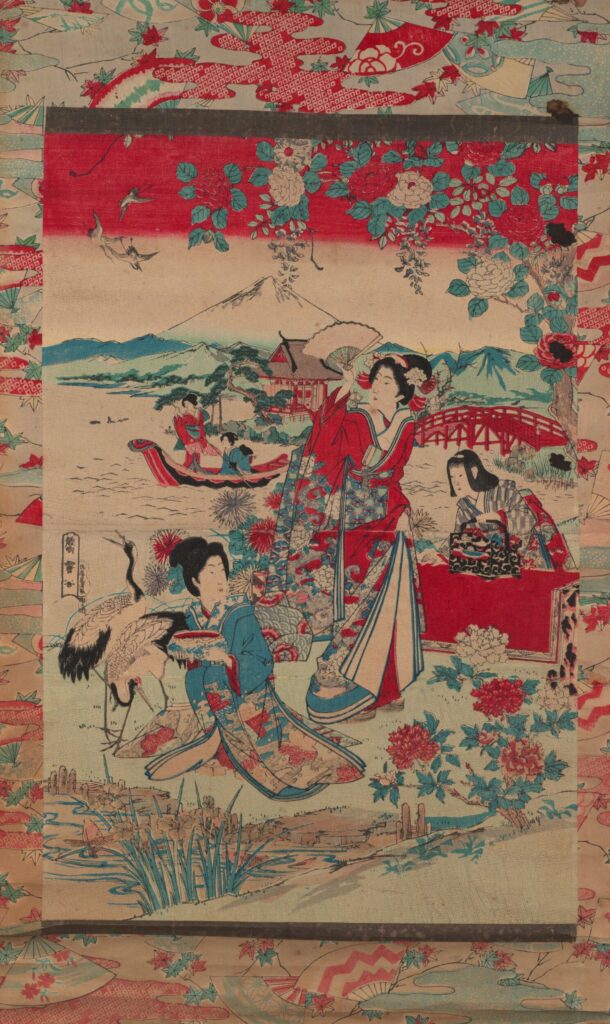

Japanese art swept through Europe in the 19th century, captivating artists, collectors, and the public. Van Gogh was among those deeply fascinated by this distant culture. Soon after arriving in Antwerp, he purchased his first Japanese woodblock print. That moment marked the beginning of his role as a dedicated print collector. Despite financial instability, he amassed an impressive collection of more than 600 prints.

He studied and copied many of them using oils, adapting their techniques to his own. This fascination had a huge impact on his style, too. His palette grew brighter and more vibrant. Even the portraits adopted subtle Asian features, echoing the figures he admired in the prints.

And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful.

Letter 686 to his brother Theo, Arles, 24 September 1888

Sato Torakiyo, Geishas in a Landscape, 1870–1880, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Van Gogh loved decorating his living space with the Japanese prints he collected. They brought him joy and comfort in difficult times. He even included some of them in his paintings, such as this self-portrait. The print behind him has been identified as Geishas in a Landscape by Satō Torakiyo.

After two years in Paris, Van Gogh sought refuge from the bustling city. He relocated to the south of France, a place he deeply romanticized. In letters to his brother, he described Arles as a distant and exotic place. He often compared it to Japan. But the change of scenery was not enough to heal his inner struggles. In reality, Van Gogh remained lonely and often misunderstood. “You know I’ve always thought it ridiculous for painters to live alone. You always lose when you’re isolated,” he wrote to Theo in 1888.

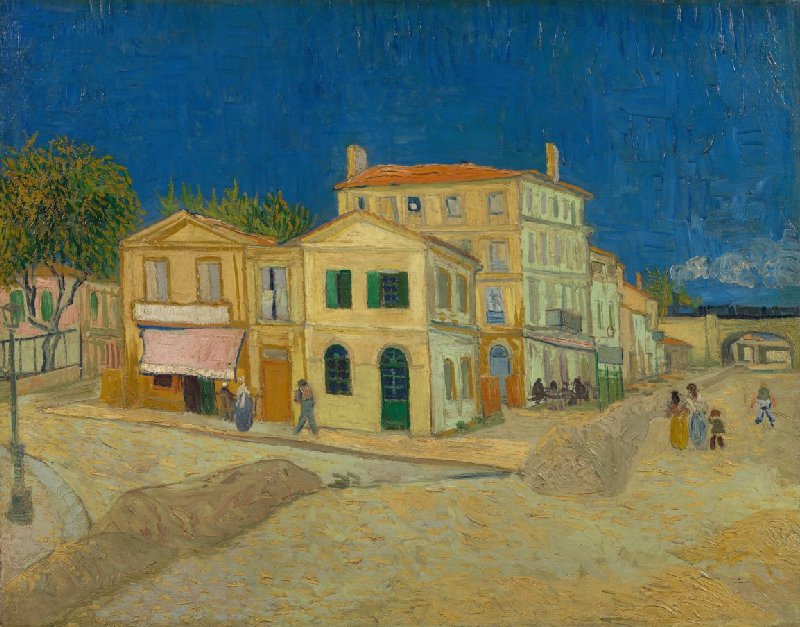

Vincent van Gogh, The Yellow House (The Street), 1888, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

He dreamed of starting an artist colony in Arles. To fulfill that dream, he rented four rooms in the “Yellow House”. After much persuasion, the fellow artist Paul Gauguin agreed to join him in Arles. Yet their time together ended far differently than Van Gogh had envisioned.

Unfortunately, the dream of an artist’s studio in the south quickly became a nightmare. Gauguin and Van Gogh often quarreled and eventually had an altercation in December 1888.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

Signs of Van Gogh’s declining mental health had appeared long before this incident. Years later, Gauguin recalled a moment when Van Gogh threatened him with a razor. Fortunately, Gauguin left the attack without any injuries. However, on the night of December 23, after their final quarrel, Van Gogh returned to his room and used the razor again—this time to cut his own ear.

The reasons remain uncertain. Some point to constant fights with Gauguin. Others note that on the same day, Vincent received news of his brother’s engagement. Relying on Theo’s support for eight years, he may have felt threatened by Theo’s obligation to his future family. He could also have envied his brother’s success in love, something Van Gogh struggled with all throughout his life. Another possibility is that he simply tried to silence the voices in his head, which is something he had been diagnosed with.

Gauguin did not return to the Yellow House that night. After learning what happened, he fled to Paris. For Van Gogh, the story took a far darker turn. He was hospitalized for two weeks following the incident. This marked the beginning of Van Gogh’s tragic decline. His condition worsened steadily, leading to admission at the mental asylum in Saint-Rémy. A week after returning to the now-empty Yellow House, he painted this self-portrait.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, Courtauld Gallery, London, UK. Detail.

The bandage in the painting appears wrapped around his right side, though he cut his left ear. This reversal occurred because Van Gogh painted self-portraits while looking in a mirror. He also wears a fur cap, purchased to help secure the bandage in place. This piece stands as a testament to the artist’s ambition and resilience. Despite mental and physical struggles, he remained determined to keep painting.

Martin Bailey: Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence, Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, 2021.

Louis van Tilborgh, Cornelia Homburg, and Nienke Bakker: Van Gogh and Japan, Yale University Press, 2018.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!