From Finland with Love: Akseli Gallen-Kallela in 10 Paintings

Akseli Gallen‑Kallela (1865–1931), one of Finland’s most famous painters, holds a distinctive place in European art at the turn of the 20th...

Catherine Razafindralambo 19 February 2026

Francisco Goya’s work includes the abundant Rococo style, formal portraiture, anti-war etchings, religious paintings, and the dark and surreal. These ten paintings will take you through his long and multifaceted career.

Francisco de Goya, The Parasol, 1777, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Goya showed an aptitude for drawing at an early age and began lessons in his home province of Aragon, Spain, with José Luzán. Luzán’s three other pupils were Francisco, Manuel, and Ramon Bayeu. Goya would marry their sister, Josefa. Francisco Bayeu was the first of the four pupils to meet success. He became a court painter and, in turn, helped Goya gain employment painting cartoons (tapestry designs) for the royal tapestry factory. The Parasol is one of these light-hearted cartoons, and the playful, romantic scene, bright colors, and ornate costumes align it with the Rococo style.

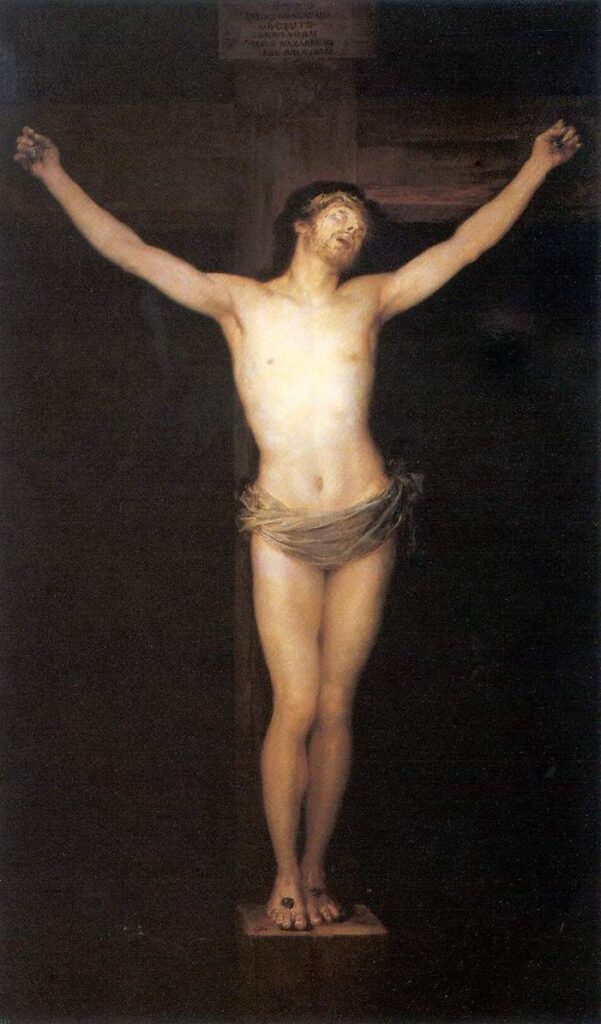

Francisco Goya, Christ Crucified, 1780, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Francisco Goya, like all artists in Spain at the time, knew religious paintings were a way to establish himself financially and to build his reputation. His fresco Adoration of the Name of God in Basílica del Pilar in Zaragoza earned him a commission equivalent to a year’s salary for a court painter.

Twice rejected from the Royal Academy of San Fernando, Goya gained admission in 1780 with the submission of Christ Crucified. No doubt this was a safe subject for the venerable institution. Also, Francisco Goya’s masterful depiction of the human form and use of light help the painting stand out from the multitude of other paintings of the same subject.

Francisco Goya, St. Francis Borja Helping a Dying Impenitent, 1788, Valencia Cathedral, Valencia, Spain.

St. Francis Borja Helping a Dying Impenitent is one of two large (350 x 300 cm; 11.4 x 14.9 in.) paintings by Francisco Goya about the life of St. Francis Borja displayed in the Valencia Cathedral. To the modern viewer, this looks like a priest performing an exorcism. However, writings about St. Francis Borja suggest it’s more likely a painting of a dying man unwilling to accept salvation. The demons are eager to take this lost soul, though not yet in possession of it. Nonetheless, the unsettling appearance of demon creatures is consistent with Goya’s later darker works. The piece was commissioned by the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, who later requested or purchased several paintings of witchcraft from Francisco Goya.

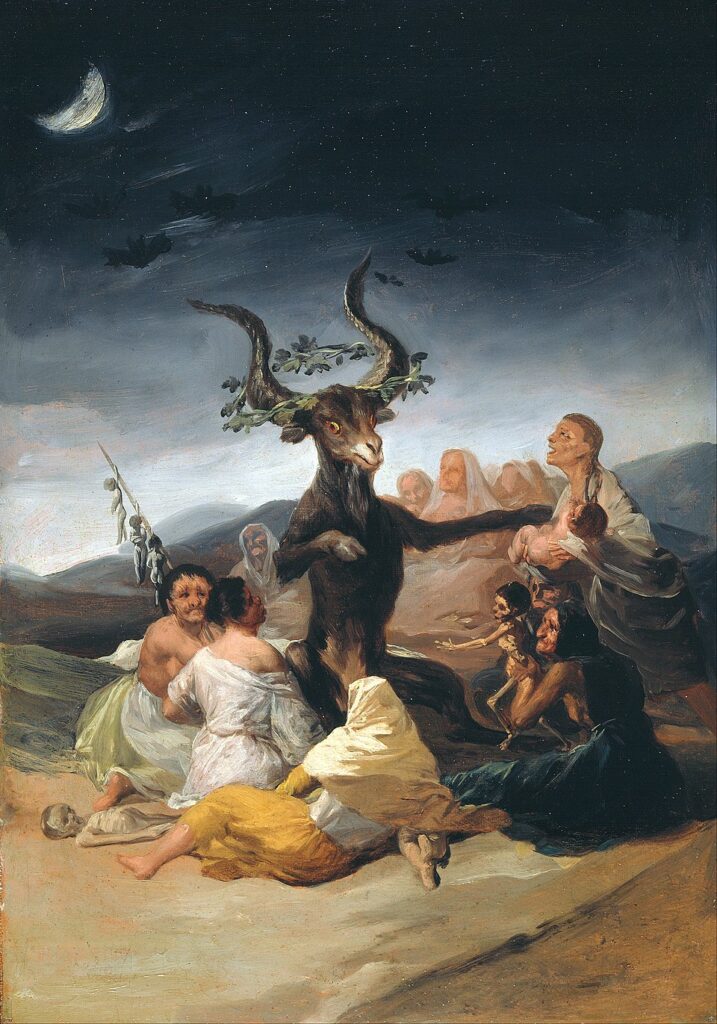

Francisco Goya, Witches’ Sabbath, 1797–1798, Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid, Spain.

Witches’ Sabbath was one of six forementioned witchcraft-themed paintings either commissioned by or purchased by the Duke and Duchess of Osuna. This painting hung in the Duchess’s bedroom. In this painting, witches pay homage to Satan in the form of a goat and offer him babies to eat. Some interpret this painting as a critique of the Spanish Inquisition or the treatment of women. Others see it as part of a generally grim turn in Goya’s work occurring around 1792 when a mysterious illness impaired his health and left him deaf.

Spain and the rest of Europe saw witchcraft as an antithesis of Christianity, and sometimes this led to persecutions and executions. Several etchings in Goya’s Los Caprichos, completed around the same time, feature witches and other ungodly creatures. Toward the end of his life, Goya completed a painting on the walls of his home of a goat figure encircled by witches. This later painting, named after the artist’s death, also carries the title Witches’ Sabbath.

Francisco Goya, Nude Maja, 1795–1800, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

It’s hard to talk about either of these paintings in isolation, so they’re included together in this list. Nude Maja was likely commissioned by Manuel Godoy, Duke of Alcudia. Godoy’s mistress, Pepita Tudo, likely served as the model. In later records, this painting is referred to as “Goya’s Venus,” placing it firmly within an artistic tradition of glorifying the beauty of the Roman goddess.

However, Godoy kept the nude in a cabinet with other “Venus” paintings by Diego Velázquez and Titian. While no doubt high art by master painters, the clandestine storage of these nudes, along with the unabashed, knowing eye contact from Goya’s Nude Maja, makes it clear they were valued, at least in part, for their salaciousness.

Francisco Goya, Clothed Maja, 1800–1807, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

In 1815, Goya was dragged in front of the Spanish Inquisition to defend the artistic merit of this painting. No doubt leaning on the tradition of others like Valáquez and Italian masters provided Goya with some plausible deniability as to the sexual allure of his Nude Maja, and he escaped the Inquisition unscathed.

Clothed Maja would have been more suitable for public display outside of Godoy’s cabinet. Nonetheless, even clothed, her pose and mischievous smile show her sensuality. In this way, Goya achieved something even more unexpected in Clothed Maja than in the controversial Nude Maja.

Francisco Goya, Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel, c. 1805, National Gallery, London, UK.

While Goya created work steeped in political upheaval, anguish, and the uncanny, he was known primarily as a portraitist. He became an official court painter in 1786 while Charles III was king. Not only did this appointment mean prestige and pay, but Goya was also stepping into the role once occupied by Velázquez, a painter he’d long admired. Over 200 of his portraits survive today and include three successive Spanish kings and other high society subjects.

Though critical of the elite ruling class, Goya spent much of his career among aristocrats. Doña Isabel de Porcel was the wife of one of Goya’s friends and a government official, and Goya painted her portrait while visiting Granada in appreciation of Porcel’s hospitality.

Francisco Goya, The Colossus, c. 1808, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Painted during the War of Spanish Independence, the looming giant in this painting is sometimes thought to represent Napoleon’s tyranny. However, scholar Nigel Glendinning claims the giant is a symbol of Spanish resistance and was inspired by a popular patriotic poem by Juan Bautista Arriaza, a portion of which can be translated to read:

See how on a peak

of that cavernous amphitheatre,

set alight by the setting of the sun

a pale Colossus is revealed

that was the Pyrenees

humble setting for his gigantic frame.Around his waist

flaming western clouds,

giving terrible expression to his stature

his eyes lit by sadness

and along with the highest mountain,

his shadow darkens the horizon.Profecía del Pirineo (Pyrenean Prophecy), 1810

In 2008, the Prado Museum cast doubt over whether or not the work was of Goya’s hand or if it would be more properly attributed to an assistant. However, Goya created other works similar to The Colossus, including Seated Giant—a print created sometime between 1800–1818. Its artistic connection to the famous painting is clear and lends further credence to the assertion that this is in fact a Goya painting. As museum leadership changed, attribution slid back to Goya.

Francisco Goya, The Third of May 1808 in Madrid, 1814, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Though Goya pledged allegiance to Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte when he took the throne in Spain, some of his works unearthed after the end of the Peninsular War made plain his heart had remained with the Spanish people. His 82-print series Disasters of War includes devastating scenes of writhing bodies and abhorrent violence. Goya created these anti-war works between 1810–1820, but they weren’t published until 1863, long after the artist’s death in 1828.

In 1814, Goya completed The Second of May 1808 in Madrid, a dynamic portrayal of a civilian uprising near the Royal Palace. The Third of May 1808 in Madrid shows the aftermath of the first painting. Those suspected of the rebellion were rounded up and shot. The terrified figure illuminated at the center of the painting stands over the bloody corpses of those killed moments before. Others cover their faces in hopeless resignation.

Whatever Romanticism was present in the valiant resistance in the first painting is wiped out by the executions shown in the second painting. The exaggerated forms and the pained facial expressions of the soon-to-be-executed central figure foreshadow the start of the Expressionist movement.

Francisco Goya, Saints Justa and Rufina, 1817, Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain.

While Goya’s work became more otherworldly and political, he retained a reputation and an inclination for religious art. He completed Saints Justa and Rufina for the Cathedral of Seville. In this piece, the venerable saints are shown under rays of divine light with a lion, perhaps a symbol of Jesus, licking their feet.

Justa and Rufina were Christian pedlars of earthenware in Seville, but they refused to sell goods to those who might use them in pagan rituals. They are pictured holding bowls and plates while a smashed pagan idol lies at their feet. In the background is the tower of the Cathedral of Seville, which the two supposedly saved during the 1504 earthquake by descending from heaven to hold it steady.

Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son, 1820–1823, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Toward the end of his life, Goya moved to the outskirts of Madrid and painted 14 works on the plaster walls of his home. They’re known as the Black Paintings. They are among his most fantastic and grim works, never named, and never intended for public view. Nearly 50 years after his death, the paintings were stripped from the walls and put onto canvas, and they now hang in the Prado Museum.

One of these Black Paintings, Saturn Devouring His Son, shows the story from Roman mythology of the god Saturn, in fear that his offspring would one day overthrow him, eating his progeny. While earlier works showed exaggerated facial expressions and twisted bodies, this depiction of Saturn stands out as perhaps Goya’s most disturbing figure. It’s one of Francisco Goya’s most recognizable paintings, and it can be viewed as the culmination of a long career that took the painter further and further away from realism and into expressionism and fantasy.

These ten paintings not only showcase Francisco Goya’s place in art history, they also show his influence on what would come later. You can see the reverberations of Goya in Edvard Munch’s The Scream and in the exaggerated facial expressions of the crowd in George Bellows’ Both Members of this Club. Goya was able to be both firmly of his time and a step ahead of it.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!