From Victim to Temptress: Salome in Art

For centuries, artists interpreted the biblical story of Salome and turned it into a lasting theme in art. But where did this fascination come from?...

Edoardo Cesarino 22 January 2026

Fanny Eaton was a regular model for the Pre-Raphaelites during the 1860s and features in a number of famous works. Yet for most of the last century, her presence was simply ignored. Jamaican-born, she nevertheless became a go-to choice for any representation of non-European or “exotic” figures. The paintings and their reception tell us much about how Black women were perceived in the past.

We know relatively little about the life of Fanny Matilda Eaton, nee Antwistle. She was born on June 23, 1835, in Jamaica, only a year after the abolition of slavery there. Both her mother, Matilda Foster, and grandmother had been born enslaved. Her father remains a mystery, but is generally thought to have been white: Eaton was recorded as mulatto (the old, pejorative term to describe a person of mixed race). Her father may have been the British soldier James Entwistle, whose death is recorded in Jamaica in July 1835.

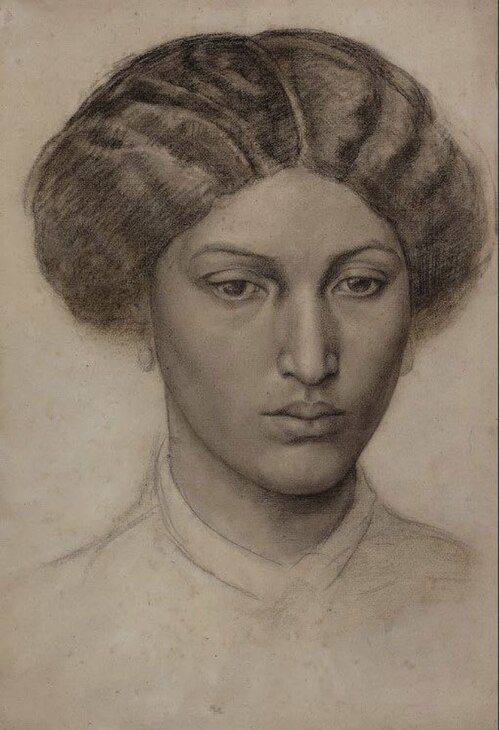

Walter Fryer Stocks, Mrs. Fanny Eaton, c. 1859, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Eaton and her mother traveled to London in the 1840s, possibly after Matilda Foster had served the six-year “apprenticeship” which all former slaves had to undertake prior to 1838. Foster became a laundress and domestic servant, and when her daughter grew up, she undertook the same work. Fanny married or cohabited with James Eaton, a cab driver, and had the first of 10 children in 1858. That they never legally married probably reflected contemporary prejudices against interracial relationships.

It is not clear exactly how Eaton began her modeling. She was employed at the Royal Academy during the 1860s, where she could earn 15 shillings per session—good wages, although the work was intermittent. It seems likely that it was there she was noticed and began to sit privately for other artists.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Study of a Young Woman (Mrs. Eaton), c. 1863–1865, Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

The Pre-Raphaelite artists, Dante Gabriel Rossetti in particular, were known to favor a particular type of feminine beauty—full lips, long, thick hair, large eyes, and strong features. Equally, they often discovered women from working-class backgrounds. They wanted real, contemporary beauty rather than a classical ideal. It was this which attracted Rossetti to Elizabeth Siddal, Fanny Cornforth, and Jane Morris.

Eaton had many of the characteristics of a Pre-Raphaelite stunner. Her strong cheekbones, large eyes, and fine head of hair are exaggerated by Rossetti in his drawing of her. For a period during the 1860s, Eaton was clearly sought after as a model whenever an exotic, foreign figure was required, or whenever these artists were looking to add variety to their work.

However, there is no suggestion that Eaton was ever more than a model for the Pre-Raphaelite painters. She was a muse, perhaps, but not a mistress, and unlike the examples above, she rarely featured as the main figure in their pictures. Ultimately, for Victorian artists, even Eaton’s undeniable beauty could not quite overcome the color of her skin.

John Everett Millais, Jephthah, 1867, National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff, UK.

In many of Eaton’s appearances in paintings, she is an insignificant background figure, a face in the crowd. In some ways, this reinforced the contemporary stereotype of Black inferiority, and certainly, many people of color were employed as servants and in menial roles in Britain at the time. Equally, however, she was a convenient choice to add variety to figure groups and allowed artists to experiment with different skin tones. The Romany model, Keomi Gray, was often employed by Pre-Raphaelite artists for the same reasons.

In John Everett Millais’ Jephthah, we see Eaton in the background wearing a yellow headscarf, recognizable but largely incidental. The painting itself tells the story of an Israelite general forced to kill his daughter after rashly promising to sacrifice the first thing he saw on his return from battle. Eaton is part of a carefully composed group of mourning attendants, in which Millais offers different heights and ages, and adds variety in hair color, pose, and dress.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Beloved (The Bride), 1865–1866, Tate Britain, London, UK.

Eaton plays a similar role in Rossetti’s The Beloved, squashed into the tight composition with only half her face visible in the top right, and next to Keomi Gray. It is particularly striking that Rossetti clearly thought of Eaton in different terms than the figure of the Black child in the foreground. The artist initially used a mixed-race girl for his model, but later repainted the work using a darker-skinned boy—his indifference to the sitter’s gender clearly shows that Rossetti was making aesthetic choices.

Both Rossetti and Millais’ works feature Black figures in the foreground in subservient roles—figures of a kind that the British public would have been familiar with from 18th-century British portraiture. Their presence emphasized the white “purity” of the paintings’ main protagonists (a virginal bride and a sacrificial victim). Equally, their role underlined contemporary ideas about Black inferiority. As a mixed-race woman with a lighter skin tone, Eaton could “pass,” she provided an acceptable balance between the conventional and the other.

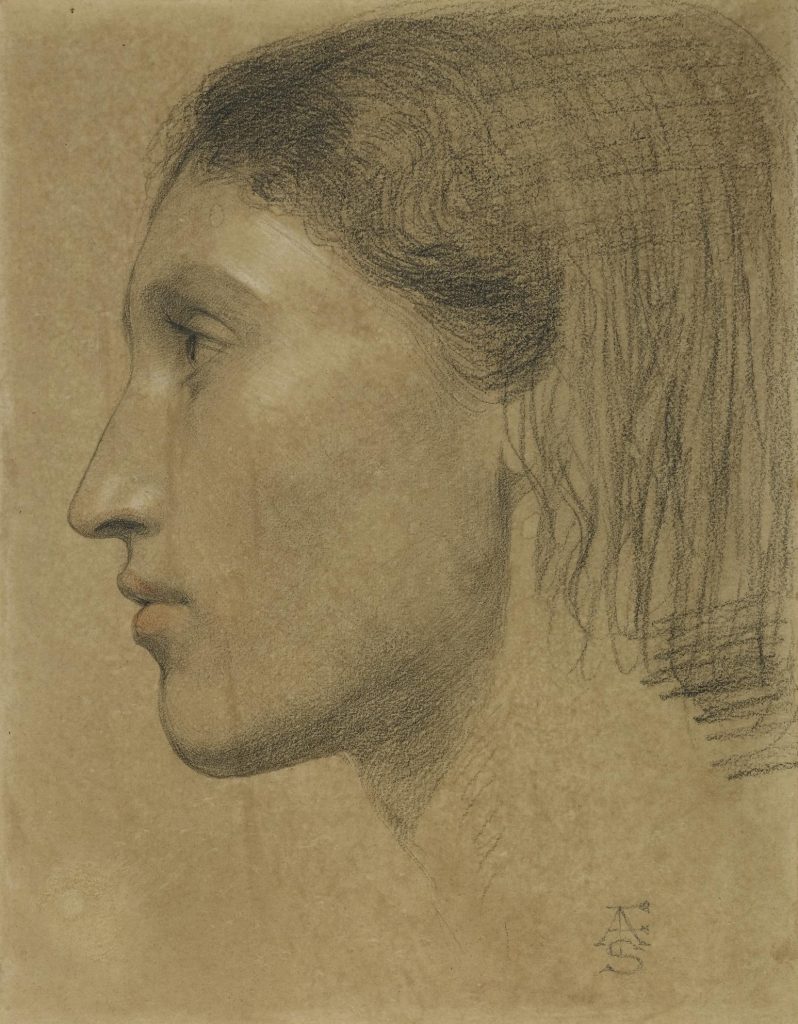

Simeon Solomon, Fanny Eaton, 1860, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The first artist that we know featured Eaton in a painting was Simeon Solomon. As a young, Jewish artist, he held a marginal status in a society that had only recently begun to give Jewish citizens equal status. Solomon’s career would later be blighted by a charge of gross indecency, and his homosexuality likely emphasized his feelings of being an outsider. He may well have empathized with a woman who shared a similar status on the edges of society.

The Mother of Moses was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1860, Solomon’s first major work. It imagines an unusual part of the Old Testament story of Moses, the moment in which his mother realizes that to save her son’s life, she must give him up. Her daughter, Miriam, stands at her side holding the basket in which they will place the baby. Through the window, just visible, a pyramid locates the scene in Egypt.

Simeon Solomon, The Mother of Moses, 1860, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE, USA.

Eaton stands in for the figure of Moses’ mother, and may well be holding her own, recently born, son. The figure of Miriam has caused debate, some suggesting it is Eaton’s daughter, although, as she was only two, this seems unlikely; others suggest that Solomon used Eaton’s own features on a younger figure.

Solomon clearly wanted to get authenticity in his representation. He possibly struggled to find a Jewish model—William Holman Hunt travelled to the Holy Land itself in order to find “real” models for Biblical works like the Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, also exhibited in 1860. Solomon’s use of Eaton sits alongside other “Orientalist” details like the patterning on Miriam’s robe as examples of Pre-Raphaelite realism.

However, most contemporary critics speculated on Eaton’s ethnicity and one criticized her as being “far too black” to represent a Biblical figure. The pose deliberately references that of a Madonna and Child and the Victorians were used to seeing religious figures presented as white.

Albert Moore, The Mother of Sisera, 1861, Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle, UK.

Solomon’s work was one of several in which Eaton stood in for Biblical characters of Jewish, Arab, or Middle Eastern origins. Albert Moore’s Mother of Sisera focuses entirely on the model’s features as she anxiously looks out of a window, awaiting the return of her son. Contemporary audiences would have been aware of the Old Testament story and would have known of the impending, implied tragedy. Sisera, a general in the Canaanite army, was killed with a tent peg by Jael while he slept. His gruesome death had often been represented by artists, but Moore was interested in the other side of the story—his mother’s pain.

Joanna Mary Boyce Wells, Fanny Eaton, 1861, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, CT, USA.

Joanna Boyce Wells’ portrait of Fanny Eaton was intended as a preliminary sketch for a painting either of Queen Zenobia of Syria or of the Libyan Sibyl. Zenobia was a warrior queen who challenged Roman hegemony. The Sybil was a character from Greek mythology considered to have foretold the coming of Christ. According to legend, she came from the region of present-day Turkey, but was usually represented as white in art, most famously by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel.

Although Wells’ portrait is often taken to be the most honest representation of Eaton, she is clearly showing her as an important and strong female figure with a silk shawl, pearl earrings, and beads in her hair. Equally, she chooses a formal profile pose reminiscent of rulers images on coins. Sadly, Wells died in childbirth before the project could progress.

Rebecca Solomon, A Young Teacher, 1861, Tate Britain/Museum of the Home, London, UK.

Solomon’s sister, Rebecca, was another woman artist who used Eaton as a model. When A Young Teacher was exhibited in 1861, there was genuine confusion among critics as to what the painting was actually about. A clearly recognizable Eaton, dressed as a servant, is shown with a small child on her knee and a slightly older sister looking at a book.

Some critics described Eaton as an ayah, an Indian nurse, and therefore implied to be the teacher herself. Rossetti would later write to Ford Madox Brown clarifying that Eaton was “not a hindoo.” The mistakes lay bare the expectations and assumptions of the Victorian audience, who were familiar with the idea of Indian servants and had little nuance in their understanding of any non-European figures.

Today, the painting is viewed very differently, as an indictment of a society where a young white girl is better educated than her Black servant. Solomon seems to be directly commenting on the commonly held view at the time that “superior” Europeans had a moral obligation to educate, convert, and Westernize the rest of the world’s population.

Frederick Sandys, Fanny Eaton, 1860, British Museum, London, UK

Eaton was a model for a relatively short period of time, yet she lived until 1924. We know virtually nothing of the rest of her life, of why she gave up modeling, or why artists stopped employing her. Her husband died in 1881, leaving her to bring up their children. One became a Royal Academy model, and another was later recorded in the census as an artist’s assistant. Eaton continued to support herself as a servant and needlewoman.

Art historians are now actively researching her story, but for most of the last century her presence was simply ignored. During her lifetime, it seems her ethnicity was both a help and a hindrance to her career as a model. It certainly illustrates the difficult, marginalized existence that people of color must have faced. Ultimately, however, Fanny Eaton was an independent woman who lived a long, full life as daughter, mother, and grandmother, as wife, widow, and as a breadwinner. We should celebrate the person behind the muse.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!