Who’s the Jester on Lady Gaga’s Harlequin Cover?

Lady Gaga released an exclusive vinyl of her new album Harlequin, and fans quickly pointed out many easter eggs the artist had left on the cover. The...

Sandra Juszczyk 22 November 2024

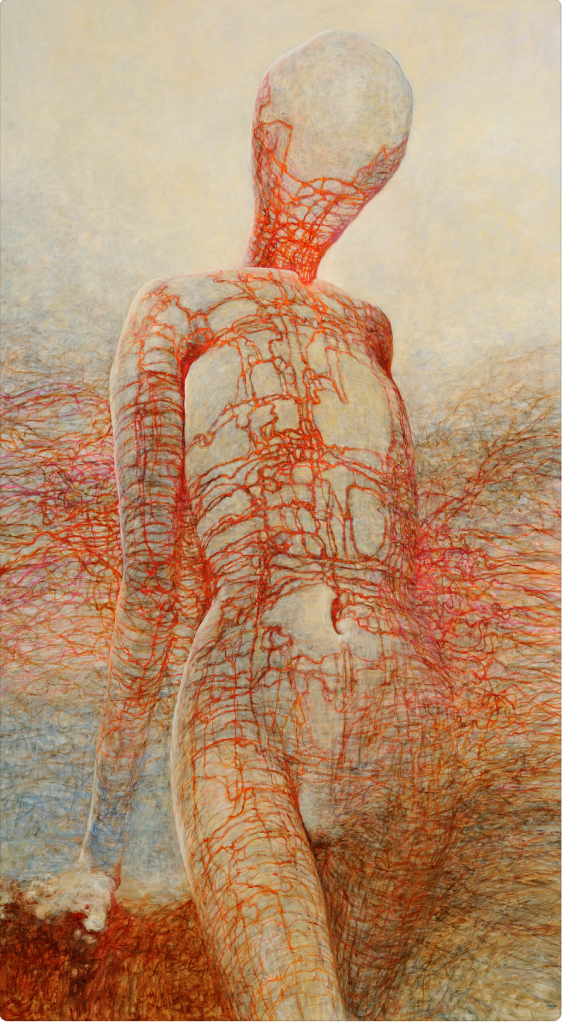

In the history of art, so much has been written and said about the close relationship between music and painting. Numerous painters have declared strong musical inspiration for their art, starting with Poussin and ending with Kandinsky, Whistler, or Chagall. Within that group, there is a special place for Zdzisław Beksiński, undoubtedly one of the greatest connoisseurs and lovers of classical music among painters.

Zdzisław Beksiński’s closeness to music dates back to his early childhood, when his mother, in hope of raising a famous musician, signed him up for piano lessons. Ever since, music played a significant role in his life. In the beginning, however, there was little enthusiasm for the music, due to never-ending and boring piano finger exercises. So, when he lost two fingertips (from a bullet, which he was trying to dismantle, exploded), to his delight, he had to quit piano lessons.

Beksiński’s musical fascinations ran along a peculiar path: from classical music, through jazz and rock, back to classical art. The first youthful contact with music was connected with an accidental acquisition of the collection of Soviet vinyl records in 1941. 12 year old Beksiński then came into contact with opera music, including Eugene Onegin and Carmen. Also during the war, using a hidden radio, he heard the overture to Tannhäuser on a German station, which made an electrifying impression on him.

After the war – in the era of socialist realism – came the fascination with jazz, which reached him through shortwave broadcasts. Finally, in the mid-1950s, rock and roll appeared. However, classical music had primacy for Beksiński. When LP vinyl records appeared, Beksiński started to collect symphonic music with pleasure. He sold the huge collection only in 1991, mainly because of the lack of space.

Beksiński paid less attention to the form in music, looking instead for a specific emotional charge which he could not or even try to describe in words. Undoubtedly, he found it to the greatest extent in the compositions of the late 19th century or early 20th century, in which emotionalism – as he said himself – was somehow inscribed in the program. He was most excited by the grand finale, during which he would put down the brush, stop working and contemplate his beloved crowning moments.

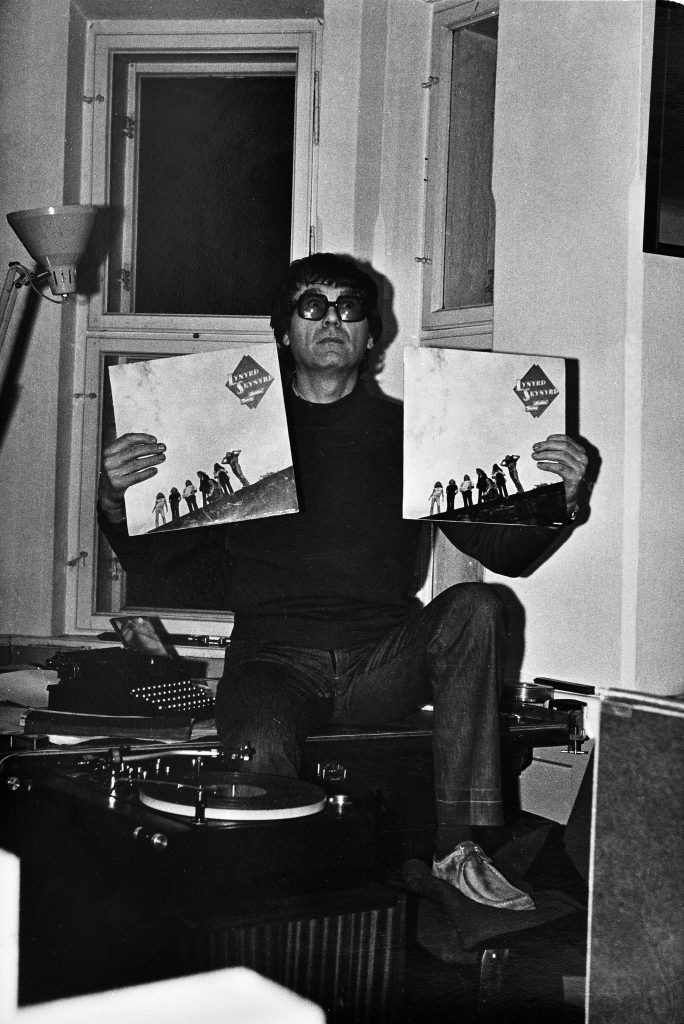

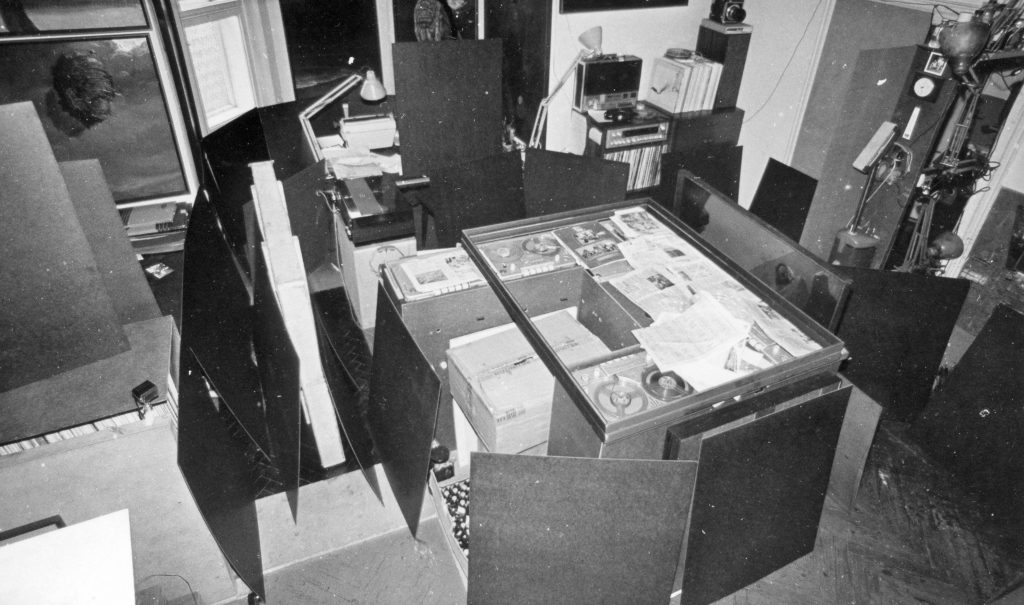

Not only did he listen to the music, but – seeking various means of expression – he also made an attempt at composing. Having collected audio equipment in his workshop (arranged in a living room of his house in Sanok), he composed some pieces. Disappointed with the results, soon he gave up. Recently, one of those pieces was used in the performance Interview, which won’t take place by Wiesław Banach.

Beksiński had great difficulty in indicating the relationship between the music he listened to and the work created in its accompaniment. Music – as he used to say – fulfilled the role of a wallpaper in the creative process. Of course, he perceived a correlation, expressed in the construction of his works in the shape of the architecture of a 19th century or early 20th century symphonic poem. However, it was difficult to point to the direct influence of specific artists here. After all, in the course of painting one picture – and it was quite a long process – he listened to hundreds of pieces composed by many composers.

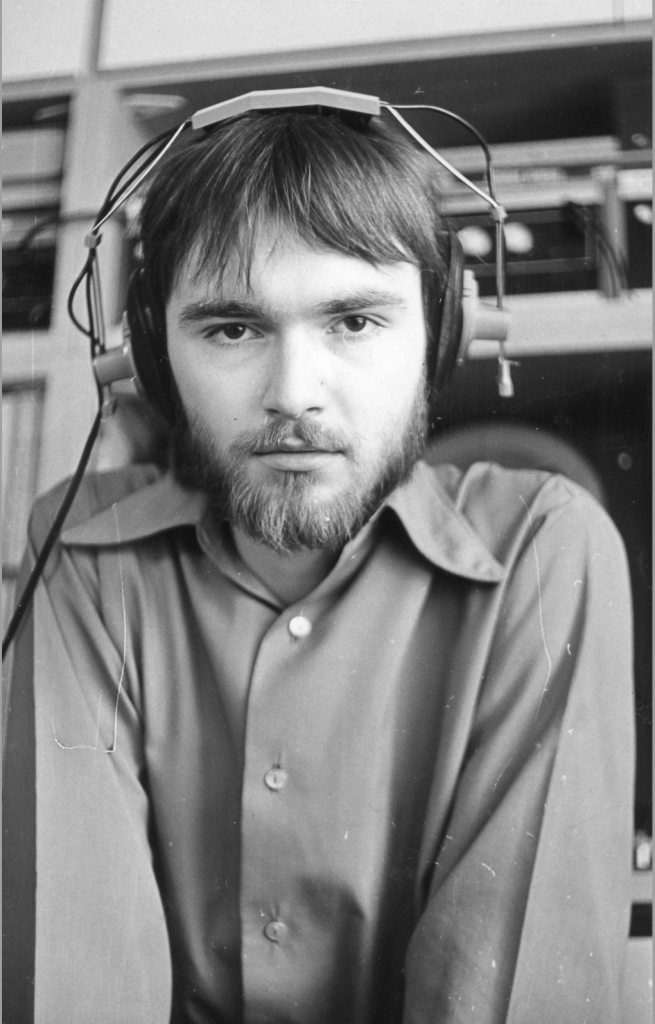

It seems, however, that music was above all a kind of stimulant, driving Beksiński to work in front of the easel. Without coffee and music, the work simply did not go. That’s why his studio, first in Sanok and then in the block of flats in Warsaw, was filled with many hours of noise. As he said:

I have had my hearing tested, to check if it’s still all right, but I have this need of music to literally smash and tear me apart. It somehow appears, that after fourteen hours of constant listening, only music allows me to paint without any break, standing up, as if there’s no exhaustion. It works better than coffee!

Zdzisław Beksiński, interviewed by Waldemar Siemiński, Sztuka jako odcisk palca, Nowy Wyraz, 1976.

Especially in Warsaw, where he lived in a block of flats, it gave rise to complaints from his neighbors. Characteristically, as Beksiński noticed, they didn’t protest when he played Pink Floyd rock music at full volume, but whenever he played classical music, there were instant complaints. Maybe it was because of the loud music that he had to use a hearing aid in his old age?

In Beksiński’s workshop, reconstructed in the Historical Museum in Sanok, one can find the amazing collection of over 1500 CDs. It’s dominated with the composers of 19th and 20th century, such as Chopin, Liszt, Grieg, Dvorak, Bruckner, Shostakovich, and Górecki. But none of them meant to Beksiński as much as Mahler and Schnittke did.

There’s no better way to get to know his playlist than to visit the Historical Museum in Sanok.

Author’s bio:

Dr Jarosław Serafin – director of the Historical Museum in Sanok, which houses the renowned Zdzisław Beksiński Gallery. A historian by education, author of publications in the field of Old Polish history. Privately an enthusiast of the works and the figure of Zdzisław Beksiński, co-organizer of temporary exhibitions of the artist abroad, among others, in Vienna, Chicago and Stockholm.

W. Banach, J. M. Skoczeń, Beksiński. Dzień po dniu kończącego się życia, Warsaw, 2016.

W. Skrodzki, Z. Beksiński, Projekt, 1981.

W. Siemiński, Sztuka jako odcisk palca, Nowy Wyraz, 1976.

T. de Laveux, interview with Zdzisław Beksiński for TV Kraków, 1992.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!