Chola Bronzes: Devotion in Metal

The bronze sculptures of the Chola period are among the most refined and enduring achievements of Indian statuary. Created between the 9th and 13th...

Maya M. Tola 12 June 2025

Abu’l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, later known as Akbar the Great, was born into uncertain circumstances in 1542, during a period of exile for his father, Humayun. Forced from the throne by the Afghan ruler Sher Shah Suri, Humayun fled to Persia, where Akbar was born in relative obscurity. At the time, few could have imagined that this child would become one of the greatest rulers in South Asian history and, adjusted for inflation, one of the wealthiest individuals in recorded history.

Humayun eventually regained control of northern India, but his sudden death in 1556 left the empire in the hands of his teenage son. Akbar, just 13 or 14 at the time, inherited the mantle of the Timurid dynasty and began a reign that would reshape the Mughal Empire. Though a formidable military strategist and revolutionary administrator, Akbar’s most enduring legacy lies in his visionary patronage of the arts.

As a Muslim emperor ruling over a predominantly Hindu population, Akbar understood that imperial stability required more than military might—it demanded cultural inclusivity and religious harmony. He dismantled many of his predecessors’ discriminatory practices, including the repressive jizya tax levied on non-Muslims. He welcomed Hindus into positions of influence, supported their arts and temples, and forged diplomatic and personal alliances through interfaith marriages.

Akbar’s atelier reflected this pluralism. Some of the era’s most accomplished painters—Govardhan, Basawan, and Daswanth—were Hindu artists whose contributions helped define Mughal visual culture. Under Akbar’s reign, classical Indian art forms like miniature painting, music, and dance flourished, not in isolation but in synthesis with Persian and Central Asian traditions. The result was the uniquely syncretic Mughal style, blending Hindu iconography with Timurid aesthetics.

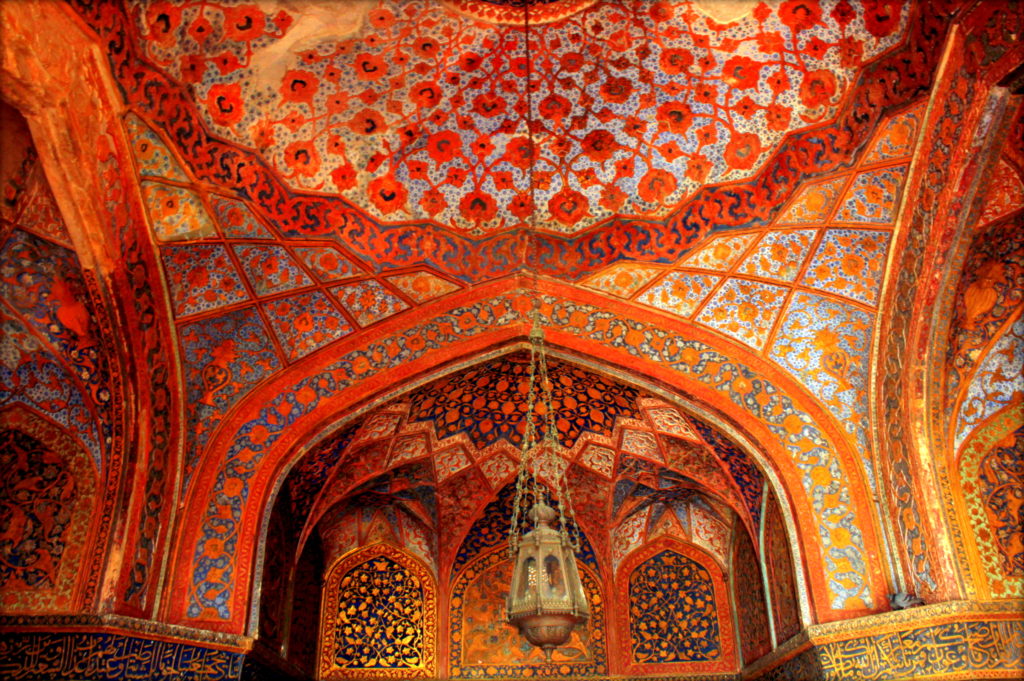

Mughal architecture under Akbar was marked by a fusion of Timurid, Persian, Indo-Islamic, and Hindu Rajasthani elements. Its distinctive features include bulbous Persian domes, lotus-shaped finials, Rajasthani arches, intricate geometric carvings, inlaid Nasta’liq calligraphy, and elaborate stone lattices or jali that softened both light and space.

The architectural renaissance began with Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, commissioned by Akbar’s stepmother Haji Begum but executed under Akbar’s supervision. It was the first major Indian monument built in red sandstone and became a prototype for later Mughal mausoleums, including the Taj Mahal. Akbar also envisioned and constructed Fatehpur Sikri, the empire’s first planned city, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This red sandstone city was both a political capital and an architectural showcase, and home to 93 protected Mughal architectural marvels, including mosques, palaces, gateways, and mausoleums.

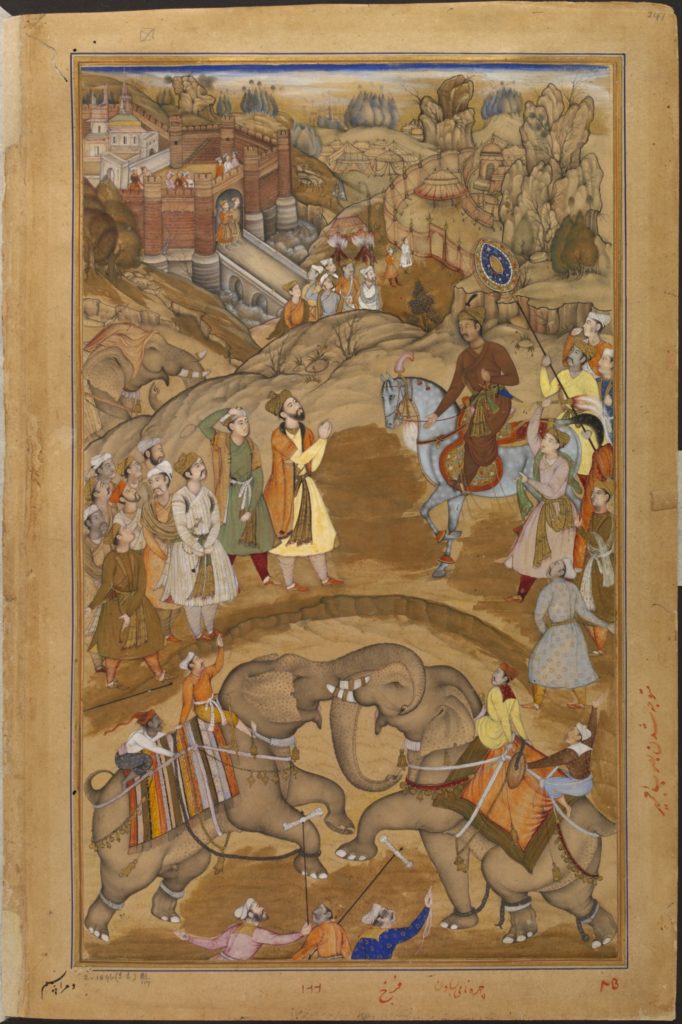

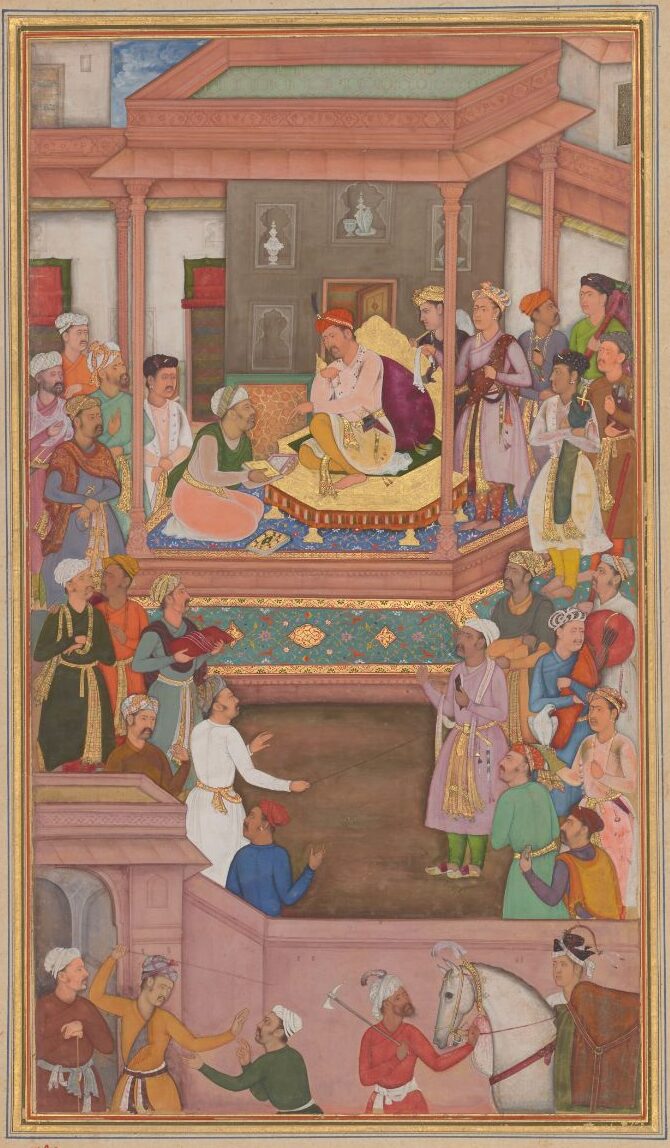

Much of what we know about Akbar’s reign comes from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), an extraordinary illustrated chronicle commissioned by the emperor himself. Authored by his close confidant and court historian Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, the three-volume work was written in Persian, which was the official language of the Mughal court. It was completed over seven years.

The Akbarnama combines historical narrative with vivid imagery in the Mughal miniature style, offering unparalleled insight into courtly life, military campaigns, governance, and diplomacy. After the fall of the Mughal Empire, the manuscript made its way into British hands and was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1896.

Much of what we know about Akbar’s reign comes from the Akbarnama (Book of Akbar), an extraordinary illustrated chronicle commissioned by the emperor himself. Authored by his close confidant and court historian Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, the three-volume work was written in Persian, which was the official language of the Mughal court. It was completed over seven years.

The Akbarnama combines historical narrative with vivid imagery in the Mughal miniature style, offering unparalleled insight into courtly life, military campaigns, governance, and diplomacy. After the fall of the Mughal Empire, the manuscript made its way into British hands and was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1896.

Akbar died in 1605 at the age of 63. Though he was once known for his fiery temperament and martial prowess, he was remembered posthumously as Arsh-Ashiyani, “one who nests at the divine throne.” He left behind not only a vast and stable empire but also a cultural renaissance whose influence would endure for centuries.

Akbar himself initiated the construction of his tomb at Sikandra, near Agra. It was completed in 1613 under the direction of his son Jahangir. The mausoleum spans 119 acres and exemplifies Mughal architectural ideals. Built with red sandstone, white marble, and intricate inlays of Persian calligraphy and geometric design, the tomb reflects the emperor’s vision of a syncretic and sophisticated empire. Long after his death, portraits of Akbar continued to be commissioned. This enduring artistic interest is a testament to his lasting presence in South Asian history and art.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!