Art history has long been written from a male’s perspective. We can all name the masters who, throughout history, shaped the canon. Yet, we rarely acknowledge the women who worked alongside them, equal, if not superior, to their male counterparts. Sure, in recent years, there has been a growing focus on certain figures, such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Frida Kahlo, Berthe Morisot, and Hilma af Klint, but several central female figures still deserve far more recognition.

One such figure is Agnes Martin, the Canadian-American painter often associated with Minimalism and Abstract Expressionism. Through her grids, lines, and monochrome paintings, Martin became one of the most prominent artists in New York during the 1960s and had a profound influence on younger generations of artists and movements.

Between the City and the Desert: A Life in Shifts

Agnes Bernice Martin was born in 1912 in Macklin, Saskatchewan, Canada, as one of four children. She grew up in a rural farming community before moving to the United States in 1931 to pursue higher education, eventually becoming an American citizen in 1950. She initially studied at Western Washington State College in Bellingham, Washington, before receiving her MA from the Teachers College of Columbia University in New York. There, she was introduced to modern art and influential figures such as Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, and Joan Miró, immersing herself in the city’s vibrant art scene.

In 1947, Martin moved to New Mexico, eventually enrolling at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, where she also taught art courses. A decade later, in 1957, she returned to New York City at the invitation of gallerist Betty Parsons, who hosted Martin’s first solo exhibition in 1958.

Upon her return, Martin became part of the Coenties Slip artist community, which included figures such as Robert Indiana and Ellsworth Kelly. Despite a successful career in New York, including exhibitions and growing recognition, Martin struggled with mental illness, specifically schizophrenia. In 1967, she abruptly left the city, stopped painting for seven years, and lived a solitary, reclusive life in New Mexico. Her seclusion came to an end in 1971 when curator Douglas Crimp approached her to organize her first non-commercial exhibition. This encounter reignited Martin’s artistic spark, and she slowly returned to painting, fully resuming her practice in 1974. She never left the desert again, spending the rest of her life in New Mexico, where she passed away in 2004.

Minimalism, Expressionism, and Beyond

Although often categorized as a Minimalist, Martin herself identified more closely with Abstract Expressionism. She believed her work was about conveying emotion and spirituality rather than formalist ideas. Her art is a delicate balance of structured, geometric precision and subtle, human imperfection.

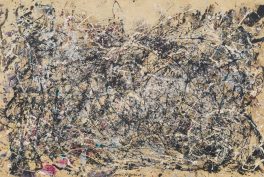

At the beginning of her career, Martin experimented with Surrealist paintings and watercolor landscapes reminiscent of her rural Canadian upbringing, works she later destroyed when shifting towards abstraction. Her signature style, developed in the late 1950s and 1960s, featured large, often square canvases covered with meticulously hand-drawn grids and lines, created primarily with acrylic paint and graphite.

Influenced by the New Mexico desert, Martin’s art is deeply characterized by serene compositions, predominantly monochromatic, that employ neutral colors like black, white, and brown. Her paintings embody tranquility and spirituality, which she derived from Asian philosophies, particularly Taoism and Zen Buddhism. For Martin, painting was a form of meditation: she sought to evoke innocence, happiness, and calm, reflected in the positive and uplifting titles of her works.

Another fundamental aspect of Martin’s art was her relationship with mental health. Described as a closeted homosexual and diagnosed with schizophrenia, she endured many personal struggles. Yet, her meditative process, restrained palette, and repetitive structures convey a different message. Her art feels like a form of healing, a resting place from turmoil. Almost like the Japanese practice of sashiko mending, her work both repaired and celebrated life through orderly beauty. Martin famously remarked, “Art work is a representation of our devotion to life,” capturing her lifelong commitment to both her craft and the restorative power of art.

Five Works to Understand Agnes Martin

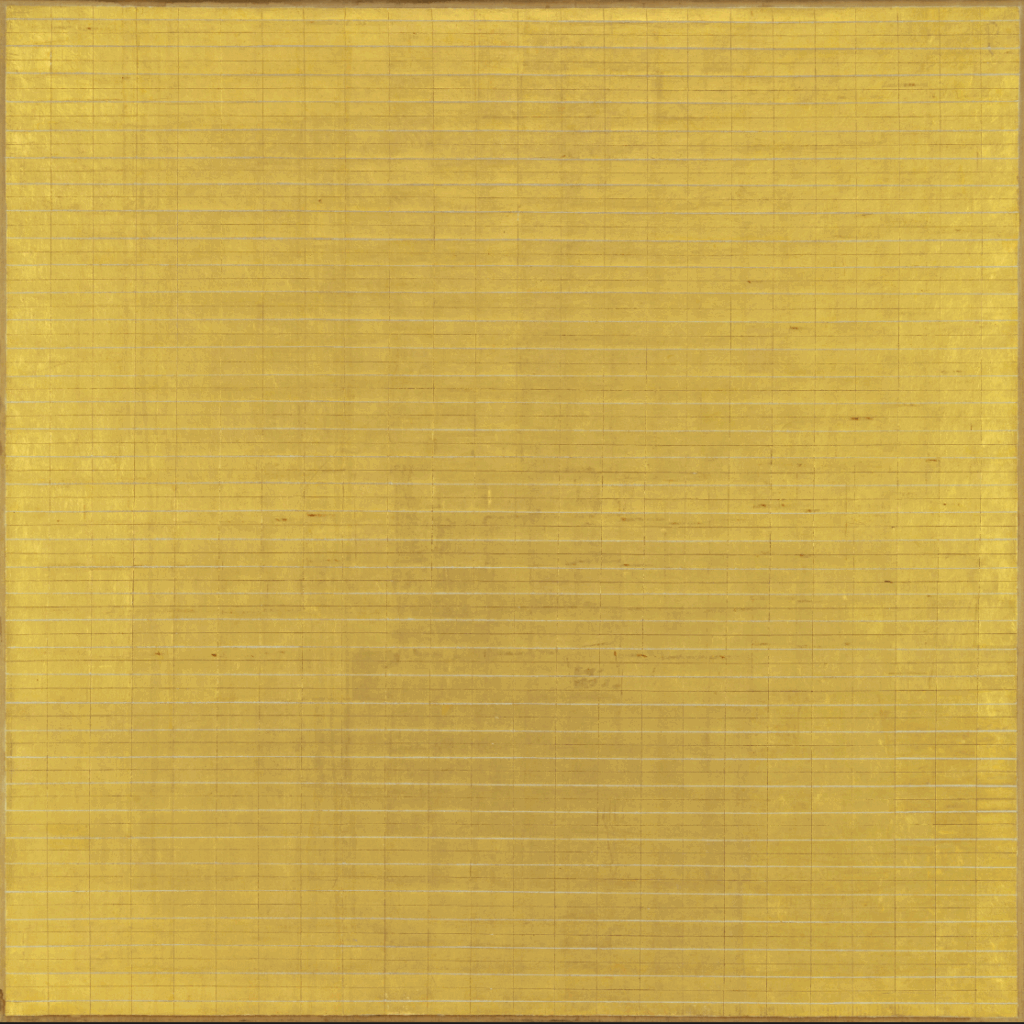

1. Friendship (1963)

A masterpiece from her early grid period, Friendship exemplifies Martin’s meticulous hand-drawn grids on a square canvas, making it a key example of how she infused emotion and personality into a seemingly rigid, geometric structure.

The painting features a thin layer of gold leaf over an underlayer of oil paint, revealed only through the grid. Although gold has connotations of luxury and opulence—contrasting with Martin’s austerity, it also evokes the religious tradition of Christian icon painting, recalling the almost mystical dimension of her practice.

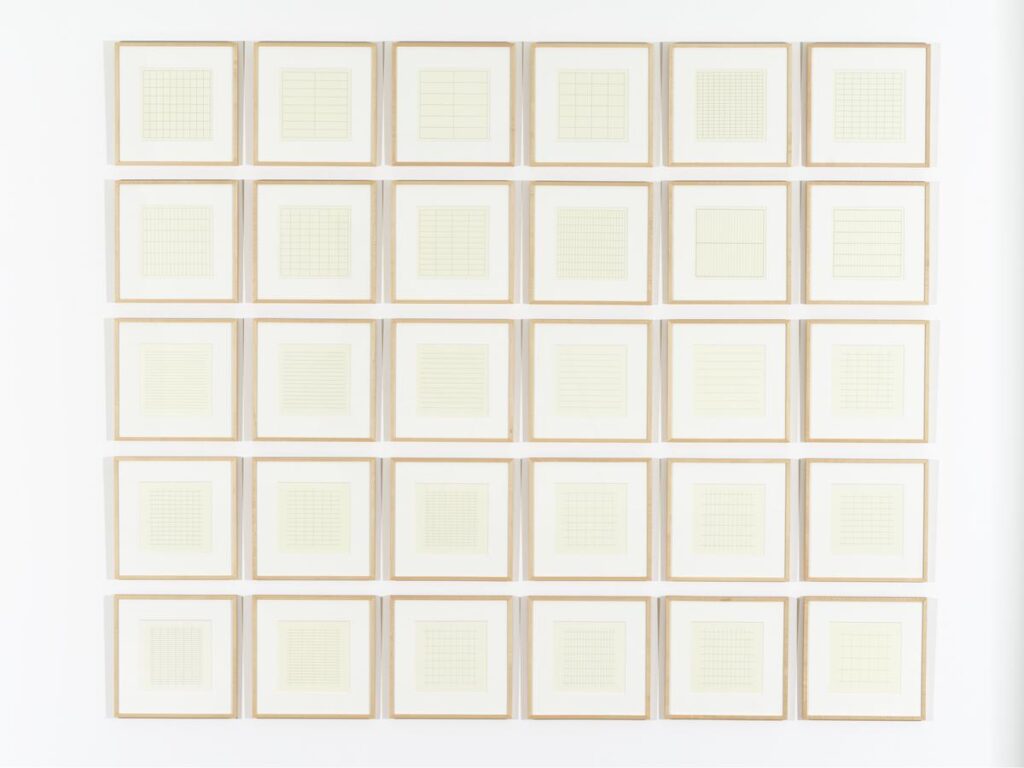

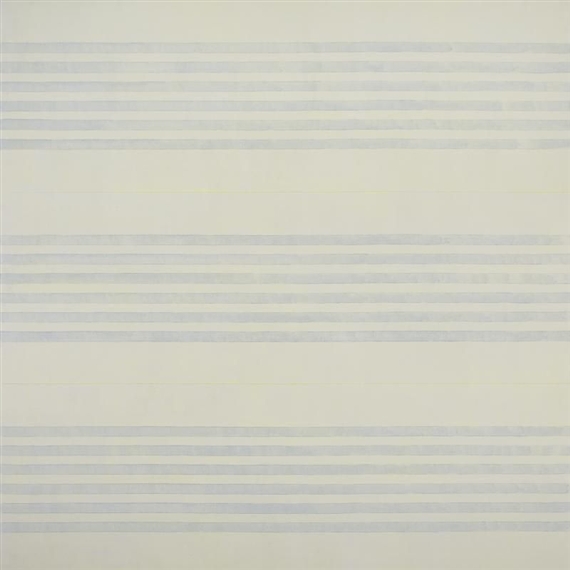

2. On a Clear Day (1973)

Moving beyond her six-by-six-foot canvas format, On a Clear Day is a portfolio of 30 screenprints created after her seven-year hiatus from painting. The series is a definitive exploration of her grid motif, showcasing subtle variations in line spacing and tonal shifts across the prints. It captures the feeling of light and clarity, demonstrating her ability to convey feeling and atmosphere through the simplest means. The title, a nod to positivity, gives structure and a context to the series, which altogether recalls the rays of light and the shadows they produce on a sunny day.

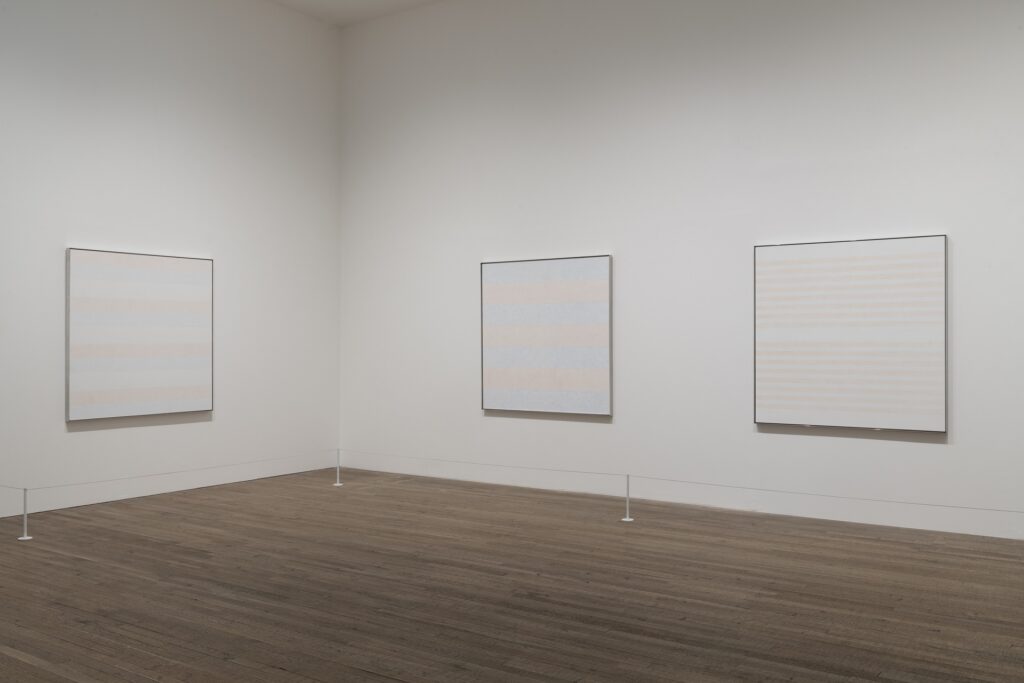

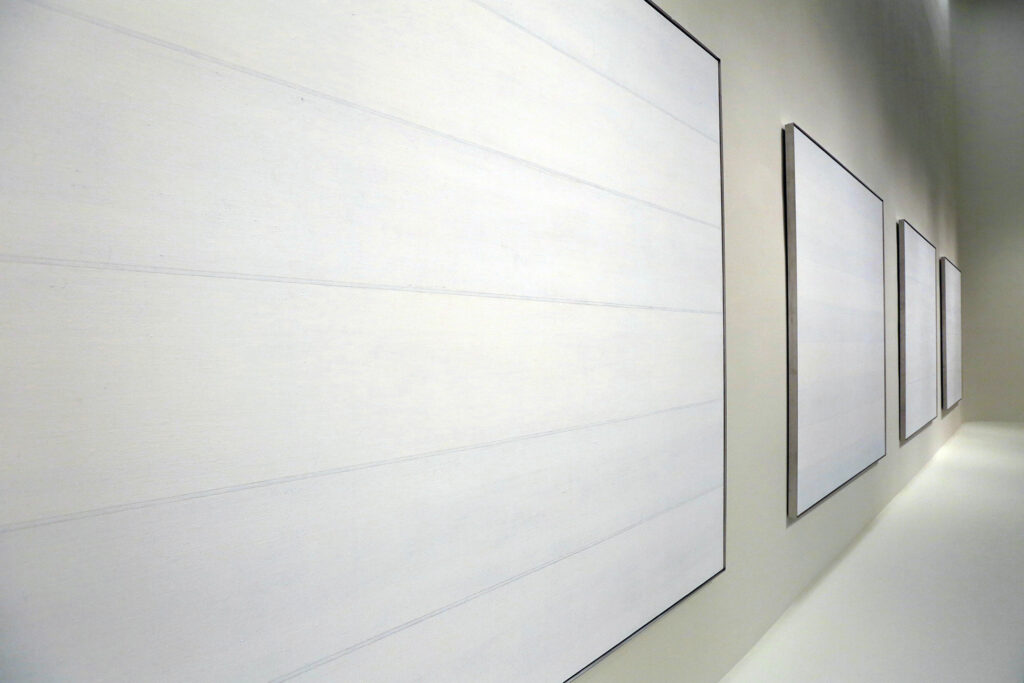

3. The Islands I–XII (1979)

After relocating to Galisteo, New Mexico in 1977, Martin’s work shifted once more, and she produced The Islands I–XII, one of only four multi-panel pieces that she made in her lifetime. It is a single work spread over 12 different canvases, always exhibited together and in the same order. Each canvas presents white or off-white bars and graphite lines, and altogether they resemble the concept of variation in classical music: each panel stems from the same idea, yet they all take an individual stance and present a variation of the original theme.

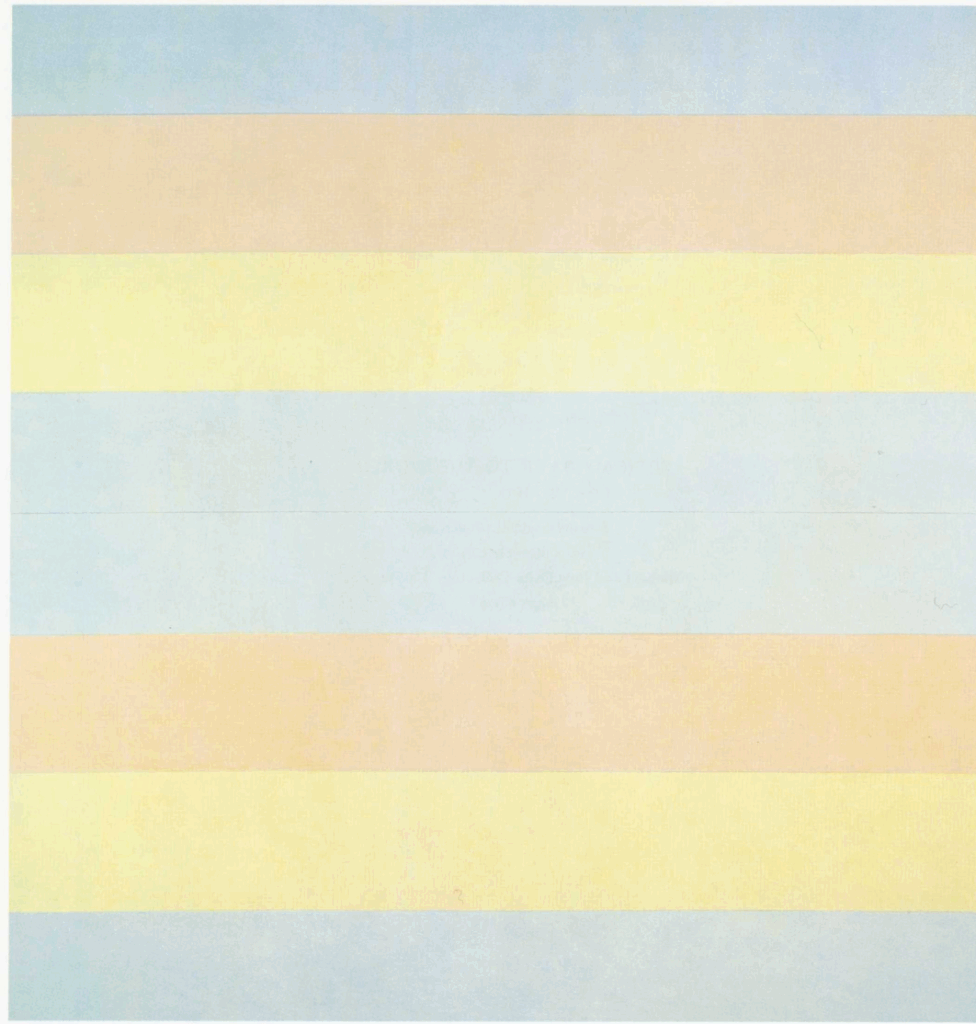

4. With My Back to the World (1997)

Another series comprising six paintings, With My Back to the World, showcases Martin’s late-career focus on horizontal stripes. The 60-by-60-inch square canvases feature broad bands of colors—pastel blue, peach, and yellow. Although they may appear identical, each canvas presents small variations that the viewers can only perceive with time, attention, and care.

The series title, moreover, encapsulates the artist’s worldview and her conception of art as something outside of the cares and corruption of the world. Martin was in her mid-80s when she created this series and was residing in an assisted living facility. Though she remained active and lucid, the size of the canvas is significantly smaller compared to earlier works, so that she could handle them more easily.

5. I Love Life (2001)

Towards the end of her career, Martin remained active and continued to produce meditative works in her signature style, characterized by bands, muted colors, and minimalistic elements. In I Love Life, the bands alternate vertically and are grouped together. The subtle gradations and soft colors create a meditative, calming effect, reflecting her desire to evoke a feeling of pure joy and happiness. The work’s title reflects Martin’s enduring optimism: even in old age, she infused her practice with joy, transforming her canvases into quiet affirmations of happiness and resilience.